Clave (rhythm)

| Music of Cuba | |

|---|---|

| General topics | |

| Related articles | |

| Genres | |

| |

| Specific forms | |

| Religious music | |

| Traditional music |

|

| Media and performance | |

| Music awards | Beny Moré Award |

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | |

| National anthem | La Bayamesa |

| Regional music | |

| |

The clave is a rhythmic pattern used as a tool for temporal organization in Afro-Cuban music. It is present in a variety of genres such as Abakuá music, rumba, conga, son, mambo, salsa, songo, timba and Afro-Cuban jazz. The five-stroke clave pattern represents the structural core of many Afro-Cuban rhythms.[1]

The clave pattern originated in sub-Saharan African music traditions, where it serves essentially the same function as it does in Cuba. In ethnomusicology, clave is also known as a key pattern,[2][3] guide pattern,[4] phrasing referent,[5] timeline,[6] or asymmetrical timeline.[7] The clave pattern is also found in the African diaspora musics of Haitian Vodou drumming, Afro-Brazilian music and Afro-Uruguayan music (candombe). The clave pattern is used in North American popular music as a rhythmic motif or ostinato, or simply a form of rhythmic decoration.

Etymology

Anglicized pronunciation: clah-vay

Clave is a Spanish word meaning 'code,' 'key,' as in key to a mystery or puzzle, or 'keystone,' the wedge-shaped stone in the center of an arch that ties the other stones together. Clave is also the name of the patterns played on claves; two hardwood sticks used in Afro-Cuban music ensembles—Peñalosa (2009).[8]

The key to Afro-Cuban rhythm

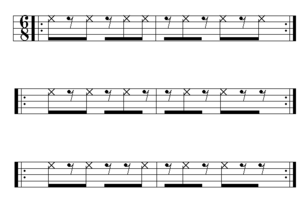

Just as a keystone holds an arch in place, the clave pattern holds the rhythm together in Afro-Cuban music.[8] The two main clave patterns used in Afro-Cuban music are known in North America as son clave and the rumba clave.[9] Both are used as bell patterns across much of Africa.[10][11][12][13] Son and rumba clave can be played in either a triple-pulse (12/8 or 6/8) or duple-pulse (4/4, 2/4 or 2/2) structure.[14] The contemporary Cuban practice is to write the duple-pulse clave in a single measure of 4/4.[15] It is also written in a single measure in ethnomusicological writings about African music.[16]

Although they subdivide the beats differently, the 12/8 and 4/4 versions of each clave share the same pulse names. The correlation between the triple-pulse and duple-pulse forms of clave, as well as other patterns, is an important dynamic of sub-Saharan-based rhythm. Every triple-pulse pattern has its duple-pulse correlative.

Son clave has strokes on: 1, 1a, 2&, 3&, 4.

4/4:

1 e & a 2 e & a 3 e & a 4 e & a || X . . X . . X . . . X . X . . . ||

12/8:

1 & a 2 & a 3 & a 4 & a || X . X . X . . X . X . . ||

Rumba clave has strokes on: 1, 1a, 2a, 3&, 4.

4/4:

1 e & a 2 e & a 3 e & a 4 e & a || X . . X . . . X . . X . X . . . ||

12/8:

1 & a 2 & a 3 & a 4 & a || X . X . . X . X . X . . ||

Both clave patterns are used in rumba. What we now call son clave (also known as Havana clave) used to be the key pattern played in Havana-style yambú and guaguancó.[17] Some Havana-based rumba groups still use son clave for yambú.[18] The musical genre known as son probably adopted the clave pattern from rumba when it migrated from eastern Cuba to Havana at the beginning of the 20th century.

During the nineteenth century, African music and European music sensibilities were blended together in original Cuban hybrids. Cuban popular music became the conduit through which sub-Saharan rhythmic elements were first codified within the context of European ('Western') music theory. The first written music rhythmically based on clave was the Cuban danzón, which premiered in 1879. The contemporary concept of clave with its accompanying terminology reached its full development in Cuban popular music during the 1940s. Its application has since spread to folkloric music as well. In a sense, the Cubans standardized their myriad rhythms, both folkloric and popular, by relating nearly all of them to the clave pattern. The veiled code of African rhythm was brought to light due to clave’s omnipresence. Consequently, the term clave has come to mean both the five-stroke pattern and the total matrix it exemplifies. In other words, the rhythmic matrix is the clave matrix. Clave is the key that unlocks the enigma; it de-codes the rhythmic puzzle. It’s commonly understood that the actual clave pattern does not need to be played in order for the music to be 'in clave'—Peñalosa (2009).[8]

One of the most difficult applications of the clave is in the realm of composition and arrangement of Cuban and Cuban-based dance music. Regardless of the instrumentation, the music for all of the instruments of the ensemble must be written with a very keen and conscious rhythmic relationship to the clave . . . Any ‘breaks’ and/or ‘stops’ in the arrangements must also be ‘in clave’. If these procedures are not properly taken into consideration, then the music is 'out of clave' which, if not done intentionally, is considered an error. When the rhythm and music are ‘in clave,’ a great natural ‘swing’ is produced, regardless of the tempo. All musicians who write and/or interpret Cuban-based music must be ‘clave conscious,’ not just the percussionists—Santos (1986).[19]

Clave theory

There are three main branches of what could be called clave theory.

Cuban popular music

First is the set of concepts and related terminology, which were created and developed in Cuban popular music from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries. In Popular Cuban Music, Emilio Grenet defines in general terms how the duple-pulse clave pattern guides all members of the music ensemble.[20] An important Cuban contribution to this branch of music theory is the concept of the clave as a musical period, which has two rhythmically opposing halves. The first half is antecedent and moving, and the second half is consequent and grounded.

Ethnomusicological studies of African rhythm

The second branch comes from the ethnomusicological studies of sub-Saharan African rhythm. In 1959, Arthur Morris Jones published his landmark work Studies in African Music, in which he identified the triple-pulse clave as the guide pattern for many musics from ethnic groups across Africa.[21] An important contribution of ethnomusicology to clave theory is the understanding that the clave matrix is generated by cross-rhythm.[22]

The 3-2 / 2-3 clave concept and terminology

The third branch comes from the United States. Ironically, there are more books published about Afro-Cuban rhythms in the U.S. than in Cuba itself. An important North American contribution to clave theory is the worldwide propagation of the 3-2/2-3 concept and terminology, which arose from the fusion of Cuban rhythms with jazz in New York City.[23]

Only in the last couple of decades have the three branches of clave theory begun to reconcile their shared and conflicting concepts. Thanks to the popularity of Cuban-based music and the vast amount of educational material available on the subject, many musicians today have a basic understanding of clave. Contemporary books that deal with clave, share a certain fundamental understanding on what clave means.

Chris Washburne considers the term to refer to the rules that govern the rhythms played with the claves. Bertram Lehman regards the clave as a concept with wide-ranging theoretical syntactic implications for African music in general, and for David Peñalosa, the clave matrix is a comprehensive system for organizing music—Toussaint (2013).[24]

Mathematical Analysis

In addition to these three branches of theory, clave has in recent years been thoroughly analyzed mathematically. The structure of clave can be understood in terms of cross-rhythmic ratios, above all, three-against-two (3:2).[25] Godfried Toussaint, a Research Professor of Computer Science, has published a book and several papers on the mathematical analysis of clave and related African bell patterns.[26][27] Toussaint uses geometry[28] and the Euclidean algorithm as a means of exploring the significance of clave.[29]

Types

Son clave

The most common clave pattern used in Cuban popular music is called the son clave, named after the Cuban musical genre of the same name. Clave is the basic period, composed of two rhythmically opposed cells, one antecedent and the other consequent.[30][31] Clave was initially written in two measures of 2/4 in Cuban music.[32] When written this way, each cell or clave half is represented within a single measure.

Three-side / two-side

The antecedent half has three strokes and is called the three-side of clave. The consequent half (second measure above) of clave has two strokes and is called the two-side.[33]

Going only slightly into the rhythmic structure of our music we find that all its melodic design is constructed on a rhythmic pattern of two measures, as though both were only one, the first is antecedent, strong, and the second is consequent, weak—Grenet (1939).[20]

[With] clave... the two measures are not at odds, but rather, they are balanced opposites like positive and negative, expansive and contractive or the poles of a magnet. As the pattern is repeated, an alternation from one polarity to the other takes place creating pulse and rhythmic drive. Were the pattern to be suddenly reversed, the rhythm would be destroyed as in a reversing of one magnet within a series... the patterns are held in place according to both the internal relationships between the drums and their relationship with clave... Should the drums fall out of clave (and in contemporary practice they sometimes do) the internal momentum of the rhythm will be dissipated and perhaps even broken—Amira and Cornelius (1992).[34]

Tresillo

In Cuban popular music, the first three strokes of son clave are also known collectively as tresillo, a Spanish word meaning triplet i.e. three equal beats in the same time as two main beats. However, in the vernacular of Cuban popular music, the term refers to the figure shown here.

Rumba clave

The other main clave pattern is the rumba clave. Rumba clave is the key pattern used in Cuban rumba. Use of the triple-pulse form of rumba clave in Cuba can be traced back to the iron bell (ekón) part in abakuá music. The form of rumba known as columbia is culturally and musically connected with abakuá which is an Afro Cuban cabildo that descends from the Kalabari of Cameroon. Columbia also uses this pattern. Sometimes 12/8 rumba clave is clapped in the accompaniment of Cuban batá drums. The 4/4 form of rumba clave is used in yambú, guaguancó and popular music.

There is some debate as to how the 4/4 rumba clave should be notated for guaguancó and yambú. In actual practice, the third stroke on the three-side and the first stroke on the two-side often fall in rhythmic positions that do not fit neatly into music notation.[37] Triple-pulse strokes can be substituted for duple-pulse strokes. Also, the clave strokes are sometimes displaced in such a way that they don't fall within either a triple-pulse or duple-pulse "grid".[38] Therefore, many variations are possible.

The first regular use of rumba clave in Cuban popular music began with the mozambique, created by Pello el Afrokan in the early 1960s. When used in popular music (such as songo, timba or Latin jazz) rumba clave can be perceived in either a 3-2 or 2-3 sequence.

Standard bell pattern

The seven-stroke standard bell pattern contains the strokes of both clave patterns. Some North American musicians call this pattern clave.[39][40] Other North American musicians refer to the triple-pulse form as the 6/8 bell because they write the pattern in two measures of 6/8.

Like clave, the standard pattern is expressed in both triple and duple-pulse. The standard pattern has strokes on: 1, 1a, 2& 2a, 3&, 4, 4a.

12/8:

1 & a 2 & a 3 & a 4 & a || X . X . X X . X . X . X ||

4/4:

1 e & a 2 e & a 3 e & a 4 e & a || X . . X . . X X . . X . X . . X ||

The ethnomusicologist A.M. Jones observes that what we call son clave, rumba clave, and the standard pattern are the most commonly used key patterns (also called bell patterns, timeline patterns and guide patterns) in Sub-Saharan African music traditions and he considers all three to be basically one and the same pattern.[41] Clearly, they are all expressions of the same rhythmic principles. The three key patterns are found within a large geographic belt extending from Mali in northwest Africa to Mozambique in southeast Africa.[42]

"6/8 clave" as used by North American musicians

In Afro-Cuban folkloric genres the triple-pulse (12/8 or 6/8) rumba clave is the archetypal form of the guide pattern. Even when the drums are playing in duple-pulse (4/4), as in guaguancó, the clave is often played with displaced strokes that are closer to triple-pulse than duple-pulse.[43] John Santos states: "The proper feel of this [rumba clave] rhythm, is actually closer to triple [pulse].”[44]

Conversely, in salsa and Latin jazz, especially as played in North America, 4/4 is the basic framework and 6/8 is considered something of a novelty and in some cases, an enigma. The cross-rhythmic structure (multiple beat schemes) is frequently misunderstood to be metrically ambiguous. North American musicians often refer to Afro-Cuban 6/8 rhythm as a feel, a term usually reserved for those aspects of musical nuance not practically suited for analysis. As used by North American musicians, "6/8 clave" can refer to one of three types of triple-pulse key patterns.

Triple-pulse standard pattern

When one hears triple-pulse rhythms in Latin jazz the percussion is most often replicating the Afro-Cuban rhythm bembé. The standard bell is the key pattern used in bembé and so with compositions based on triple-pulse rhythms, it is the seven-stroke bell, rather than the five-stroke clave that is the most familiar to jazz musicians. Consequently, some North American musicians refer to the triple-pulse standard pattern as "6/8 clave."[39][40]

Triple-pulse rumba clave

Some refer to the triple-pulse form of rumba clave as "6/8 clave." When rumba clave is written in 6/8 the four underlying main beats are counted: 1, 2, 1, 2.

1 & a 2 & a |1 & a 2 & a || X . X . . X |. X . X . . ||

Claves... are not usually played in Afro-Cuban 6/8 feels... [and] the clave [pattern] is not traditionally played in 6/8 though it may be helpful to do so to relate the clave to the 6/8 bell pattern—Thress (1994).[45]

The main exceptions are: the form of rumba known as Columbia, and some performances of abakuá by rumba groups, where the 6/8 rumba clave pattern is played on claves.

Triple-pulse son clave

Triple-pulse son clave is the least common form of clave used in Cuban music. It is however, found across an enormously vast area of sub-Saharan Africa. The first published example (1920) of this pattern identified it as a hand-clap part accompanying a song from Mozambique.[46]

Cross-rhythm and the correct metric structure

Because 6/8 clave-based music is generated from cross-rhythm, it is possible to count or feel the 6/8 clave in several different ways. The ethnomusicologist A.M. Jones correctly identified the importance of this key pattern, but he mistook its accents as indicators of meter rather than the counter-metric phenomena they actually are. Similarly, while Anthony King identified the triple-pulse "son clave" as the ‘standard pattern’ in its simplest and most basic form, he did not correctly identify its metric structure. King represented the pattern in a polymetric 7/8 + 5/8 time signature.[47]

It wasn't until African musicologists like C.K. Ladzekpo entered into the discussion in the 1970s and 80s that the metric structure of sub-Saharan rhythm was unambiguously defined. The writings of Victor Kofi Agawu and David Locke must also be mentioned in this regard.[22][48]

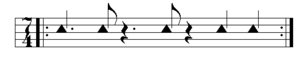

In the diagram below 6/8 (son) clave is shown on top and a beat cycle is shown below it. Any or all of these structures may be the emphasis at a given point in a piece of music using the "6/8 clave."

The example on the left (6/8) represents the correct count and ground of the "6/8 clave".[49] The four dotted quarter-notes across the two bottom measures are the main beats. All clave patterns are built upon four main beats.[50][51][52] The bottom measures on the other two examples (3/2 and 6/4) show cross-beats. Observing the dancer’s steps almost always reveals the main beats of the music. Because the main beats are usually emphasized in the steps and not the music, it is often difficult for an "outsider" to feel the proper metric structure without seeing the dance component. Kubik states: "In order to understand the motional structure of any music in Africa, one has to look at the dancers as well and see how they relate to the instrumental background" (2010: 78).[53]

For cultural insiders, identifying the... ‘dance feet’ occurs instinctively and spontaneously. Those not familiar with the choreographic supplement, however, sometimes have trouble locating the main beats and expressing them in movement. Hearing African music on recordings alone without prior grounding in its dance-based rhythms may not convey the choreographic supplement. Not surprisingly, many misinterpretations of African rhythm and meter stem from a failure to observe the dance.— Agawu, (2003)[54]

3-2 / 2-3 clave concept and terminology

In Cuban popular music, a chord progression can begin on either side of clave. When the progression begins on the three-side, the song or song section is said to be in 3-2 clave. When the chord progression begins on the two-side, it is in 2-3 clave. In North America, salsa and Latin jazz charts commonly represent clave in two measures of cut-time (2/2); this is most likely the influence of jazz conventions.[55] When clave is written in two measures (right), changing from one clave sequence to the other is a matter of reversing the order of the measures.

Chord progression begins on the three-side (3-2)

A guajeo is a typical Cuban ostinato melody, most often consisting of arpeggiated chords in syncopated patterns. Guajeos are a seamless blend of European harmonic and African rhythmic structures. Most guajeos have a binary structure that expresses clave.

Clave motif

Kevin Moore states: "There are two common ways that the three-side is expressed in Cuban popular music. The first to come into regular use, which David Peñalosa calls 'clave motif,' is based on the decorated version of the three-side of the clave rhythm."[56] The following guajeo example is based on a clave motif. The three-side (first measure) consists of the tresillo variant known as cinquillo.

Since this chord progression begins on the three-side, the song or song section is said to be in 3-2 clave.

Offbeat/onbeat motif

Moore: "By the 1940s [there was] a trend toward the use of what Peñalosa calls the 'offbeat/onbeat motif.' Today, the offbeat/onbeat motif method is much more common."[56] With this type of guajeo motif, the three-side of clave is expressed with all offbeats. The following I-IV-V-IV progression is in a 3-2 clave sequence. It begins with an offbeat pick-up on the pulse immediately before beat 1. With some guajeos, offbeats at the end of the two-side, or onbeats at the end of the three-side serve as pick-ups leading into the next measure (when clave is written in two measures).

Chord progression begins on the two-side (2-3)

Clave motif

A chord progression can begin on either side of clave. One can therefore be on either the three-side or the two-side because the harmonic progression, rather than the rhythmic progression, is the primary referent.[57] The following guajeo is based on the clave motif in a 2-3 sequence. The cinquillo rhythm is now in the second measure.

Onbeat/offbeat motif

This guajeo is in 2-3 clave because it begins on the downbeat, emphasizing the onbeat quality of the two-side. The figure has the same harmonic sequence as the earlier offbeat/onbeat example, but rhythmically, the attack-point sequence of the two measures is reversed. Most salsa is in 2-3 clave, and most salsa piano guajeos are based on the 2-3 onbeat/offbeat motif.

Going from one side of clave to the other within the same song

The 3-2/2-3 concept and terminology was developed in New York City during the 1940s by Cuban-born Mario Bauza while he was the music director of Machito and his Afro-Cubans.[58] Bauzá was a master at moving the song from one side of clave to the other.

The following melodic excerpt is taken from the opening verses of "Que vengan los rumberos" by Machito and his Afro-Cubans. Notice that the melody goes from one side of clave to the other and then back again. A measure of 2/4 moves the chord progression from the two-side (2-3), to the three-side (3-2). Later, another measure of 2/4 moves the start of the chord progression back to two-side (2-3).

According to David Peñalosa:

The first 4 1⁄2 claves of the verses are in 2-3. Following the measure of 2/4 (half clave) the song flips to the three-side. It continues in 3-2 on the V7 chord for 4 1⁄2 claves. The second measure of 2/4 flips the song back to the two-side and the I chord.In songs like "Que vengan los rumberos", the phrases continually alternate between a 3-2 framework and a 2-3 framework. It takes a certain amount of flexibility to repeatedly reorder your orientation in this way. The most challenging moments are the truncations and other transitional phrases where you "pivot" in order to move your point of reference from one side of clave to the other.

Working in conjunction with the chord and clave changes, vocalist Frank "Machito" Grillo creates an arc of tension/release spanning more than a dozen measures. Initially Machito sings the melody straight (first line), but soon expresses the lyrics in the freer and more syncopated inspiración of a folkloric rumba (second line). By the time the song changes to 3-2 on the V7 chord, Machito has developed a considerable amount of rhythmic tension by contradicting the underlying meter. That tension is then resolved when he sings on three consecutive main beats (quarter-notes), followed by tresillo. In the measure immediately following tresillo the song returns to 2-3 and the I chord (fifth line).[59]

Tito Puente learned the concept from Bauzá.[58] Tito Puente's "Philadelphia Mambo" is an example of a song that moves from one side of clave to the other. The technique eventually became a staple of composing and arranging in salsa and Latin jazz. According to Kevin Moore:

Clave direction is relative while clave alignment is absolute. If you walk from New York to Miami, you're walking south; if you walk from Miami to New York, you're walking north. But if you put your left shoe on your right foot, (i.e., if your shoes are cruzado), it's going to be a very awkward walk in either direction. Your shoes remain "aligned" (or misaligned) with your feet regardless of the direction your feet are taking you, and regardless of how poorly they fit.[60]

Cuban folkloric musicians do not use the 3-2/2-3 system. Many Cuban performers of popular music do not use it either. The great Cuban conga player and band leader Mongo Santamaría said, "Don’t tell me about 3-2 or 2-3! In Cuba we just play. We feel it, we don’t talk about such things."[61] In another book, Santamaría said, "In Cuba we don’t think about [clave]. We know that we’re in clave. Because we know that we have to be in clave to be a musician."[62] According to Cuban pianist Sonny Bravo, the late Charlie Palmieri would insist that, "There’s no such thing as 3-2 or 2-3, there’s only one clave!"[63] The contemporary Cuban bassist, composer and arranger Alain Pérez flatly states: "In Cuba we do not use that 2-3, 3-2 formula... 2-3, 3-2 [is] not used in Cuba. That is how people learn Cuban music outside Cuba."[64]

In non-Cuban music

Controversy over use and origins

Perhaps the greatest testament to the musical vitality of the clave is the spirited debate it engenders, both in terms of musical usage and historical origins. This section presents examples from non-Cuban music, which some musicians (not all) hold to be representative of clave. The most common claims, those of Brazilian and subsets of American popular music, are described below.

In Africa

A widely used bell pattern

Clave is a Spanish word and its musical usage as a pattern played on claves was developed in the western part of Cuba, particularly the cities of Matanzas and Havana.[65] Some writings have claimed that the clave patterns originated in Cuba. One frequently repeated theory is that the triple-pulse African bell patterns morphed into duple-pulse forms as a result of the influence of European musical sensibilities. "The duple meter feel [of 4/4 rumba clave] may have been the result of the influence of marching bands and other Spanish styles . . ."— Washburne (1995).[66]

However, the duple-pulse forms have existed in sub-Saharan Africa for centuries. The patterns the Cubans call clave are two of the most common bell parts used in Sub-Saharan African music traditions. Natalie Curtis,[67] A.M. Jones,[68] Anthony King and John Collins document the triple-pulse forms of what we call “son clave” and “rumba clave” in West, Central and East Africa. Francis Kofi[69] and C.K. Ladzekpo[70] document several Ghanaian rhythms that use the triple or duple-pulse forms of "son clave." Royal Harington[71] identifies the duple-pulse form of "rumba clave" as a bell pattern used by the Yoruba and Ibo of Nigeria, West Africa. There are many recordings of traditional African music where one can hear the five-stroke "clave" used as a bell pattern.[72]

Popular dance music

Cuban music has been popular in sub-Saharan Africa since the mid twentieth century. To the Africans, clave-based Cuban popular music sounded both familiar and exotic.[73] Congolese bands started doing Cuban covers and singing the lyrics phonetically. Soon, they were creating their own original Cuban-like compositions, with lyrics sung in French or Lingala, a lingua franca of the western Congo region. The Congolese called this new music rumba, although it was really based on the son. The Africans adapted guajeos to electric guitars, and gave them their own regional flavor. The guitar-based music gradually spread out from the Congo, increasingly taking on local sensibilities. This process eventually resulted in the establishment of several different distinct regional genres, such as soukous.[74]

Soukous

The following soukous bass line is an embellishment of clave.[75]

Banning Eyre distills down the Congolese guitar style to this skeletal figure, where clave is sounded by the bass notes (notated with downward stems).[76]

Highlife

Highlife was the most popular genre in Ghana and Nigeria during the 1960s. This arpeggiated highlife guitar part is essentially a guajeo.[77] The rhythmic pattern is known in Cuba as baqueteo. The pattern of attack-points is nearly identical to the 3-2 clave motif guajeo shown earlier in this article. The bell pattern known in Cuba as clave, is indigenous to Ghana and Nigeria, and is used in highlife.[78]

Afrobeat

The following afrobeat guitar part is a variant of the 2-3 onbeat/offbeat motif.[79] Even the melodic contour is guajeo-based. 2-3 clave is shown above the guitar for reference only. The clave pattern is not ordinarily played in afrobeat.

Guide-patterns in Cuban versus non-Cuban music

There is some debate as to whether or not clave, as it appears in Cuban music, functions in the same way as its sister rhythms in other forms of music (Brazilian, North American and African). Certain forms of Cuban music demand a strict relationship between the clave and other musical parts, even across genres. This same structural relationship between the guide-pattern and the rest of the ensemble is easily observed in many sub-Saharan rhythms, as well as rhythms from Haiti and Brazil. However, the 3-2/2-3 concept and terminology is limited to certain types of Cuban-based popular musics and is not used in the music of Africa, Haiti, Brazil or in Afro-Cuban folkloric music. In American pop music the clave pattern tends to be used as an element of rhythmic color, rather than a guide-pattern and as such is superimposed over many types of rhythms.

In Brazilian music

Both Cuba and Brazil imported Yoruba, Fon and Congolese slaves. Therefore, it is not surprising that we find the bell pattern the Cubans call clave in the Afro-Brazilian musics of Macumba and Maculelê (dance).[80] "Son clave" and "rumba clave" are also used as a tamborim part in some batucada arrangements. The structure of Afro-Brazilian bell patterns can be understood in terms of the clave concept (see below). Although a few contemporary Brazilian musicians have adopted the 3-2/2-3 terminology, it is traditionally not a part of the Brazilian rhythmic concept.

Bell pattern 1 is used in maculelê (dance) and some Candomblé and Macumba rhythms. Pattern 1 is known in Cuba as son clave. Bell 2 is used in afoxê and can be thought of as pattern 1 embellished with four additional strokes. Bell 3 is used in batucada. Pattern 4 is the maracatu bell and can be thought of as pattern 1 embellished with four additional strokes.

![]() Example in a Pixinguinha choro music

Example in a Pixinguinha choro music

Bossa nova pattern

The so-called "bossa nova clave" (or "Brazilian clave") has a similar rhythm to that of the son clave, but the second note on the two-side is delayed by one pulse (subdivision). The rhythm is typically played as a snare rim pattern in bossa nova music. The pattern is shown below in 2/4, as it is written in Brazil. In North American charts it is more likely to be written in cut-time.

According to drummer Bobby Sanabria the Brazilian composer Antonio Carlos Jobim, who developed the pattern, considers it to be merely a rhythmic motif and not a clave (guide pattern). Jobim later regretted that Latino musicians misunderstood the role of this bossa nova pattern.[81]

Other Brazilian examples

The examples below are transcriptions of several patterns resembling the Cuban clave that are found in various styles of Brazilian music, on the ago-gô and surdo instruments.

Legend: Time signature: 2/4; L=low bell, H=high bell, O = open surdo hit, X = muffled surdo hit, and | divides the measure:

- Style: Samba 3:2; LL.L.H.H|L.L.L.H. (More common 3:2: .L.L.H.H|L.L.L.H.)

- Style: Maracatu 3:2; LH.HL.H.|L.H.LH.H

- Style: Samba 3:2; L|.L.L..L.|..L..L.L|

- Instrument: 3rd Surdo 2:3; X...OO.O|X...O.O.

- Variation of samba style: Partido Alto 2:3; L.H..L.L|.H..L.L.

- Style: Maracatu 2:3; L.H.L.H.|LH.HL.H.

- Style: Samba-Reggae or Bossanova 3:2; O..O..O.|..O..O..

- Style: Ijexa 3:2; LL.L.LL.|L.L.L.L. (HH.L.LL.|H.H.L.L.)

For 3rd example above, the clave pattern is based on a common accompaniment pattern played by the guitarist. B=bass note played by guitarist's thumb, C=chord played by fingers.

&|1 & 2 & 3 & 4 &|1 & 2 & 3 & 4 &|| C|B C . C B . C .|B . C . B C . C||

The singer enters on the wrong side of the clave and the ago-gô player adjusts accordingly. This recording cuts off the first bar so that it sounds like the bell comes in on the third beat of the second bar. This is suggestive of a pre-determined rhythmic relationship between the vocal part and the percussion, and supports the idea of a clave-like structure in Brazilian music.

In Jamaican and French Caribbean music

The son clave rhythm is present in Jamaican mento music, and can be heard on 1950s-era recordings such as "Don’t Fence Her In", "Green Guava" or "Limbo" by Lord Tickler, "Mango Time" by Count Lasher, "Linstead Market/Day O" by The Wigglers, "Bargie" by The Tower Islanders, "Nebuchanezer" by Laurel Aitken and others. The Jamaican population is partly of the same origin (Congo) as many Cubans, which perhaps explains the shared rhythm. It is also heard frequently in Martinique's biguine and Dominica's Jing ping. Just as likely however is the possibility that claves and the clave rhythm spread to Jamaica, Trinidad and the other small islands of the Caribbean through the popularity of Cuban son recordings from the 1920s onward.

In African-American music

Tresillo foundation

[There] is an absence of drums and complex polyrhythms in early blues; there is, in addition, the very specific absence of . . . timeline patterns in virtually all early twentieth-century U.S. African American music, except in cases where these patterns were borrowed from Puerto Rico or Cuba. Only in New Orleans genres does a hint of simple timeline patterns [occur]. . . These do not function in the same way as African timeline patterns—Kubik (1999: 51)[82]

While key patterns were absent from early twentieth-century African American music, tresillo, the first half of clave, has been present since at least the mid nineteenth century. Wynton Marsalis considers tresillo to be the "clave" of New Orleans.[83] The use of tresillo and its variant, the habanera rhythm, in African American music was reinforced by consecutive waves of Cuban popular music, beginning with the habanera (Cuban contradanza).[84] For the more than quarter-century in which the cakewalk, ragtime, and proto-jazz were forming and developing, the habanera was a consistent part of African American popular music.[85] Afro-Cuban music became the conduit through which African American music was "re-Africanized," through the adoption of figures like clave and instruments like the conga drum, bongos, maracas and claves.

Jazz

Although clave-like phrases are found in early twentieth-century African American music, the use of the clave pattern as an overt rhythmic motif does not appear until the 1940s with the birth of Afro-Cuban jazz (or Latin jazz). The first original jazz composition to be overtly based in-clave was "Tanga" (1942) by Mario Bauza.

Bauzá introduced be-bop innovator Dizzy Gillespie to the Cuban conga drummer Chano Pozo. The short musical collaboration of Gillespie and Pozo introduced Cuban rhythms into mainstream jazz. However, their groundbreaking experiments did not always mesh rhythmically. For example, in their 1948 performance of "Manteca" the clave pattern is played in 3-2, while the rest of the band is in 2-3. Despite its initial problems in performance, "Manteca" proved to be a strong composition and it stands today as the first jazz standard to be based in clave.

R&B

The use of clave in R&B coincided with the growing dominance of the backbeat, and the rising popularity of Cuban music in the U.S. In a sense, clave can be distilled down to tresillo (three-side) answered by the backbeat (two-side).[86]

New Orleans musicians such as Dave Bartholomew and Professor Longhair incorporated Cuban instruments as well as the clave pattern and related two-celled figures in songs such as "Carnival Day," (Bartholomew 1949) and "Mardi Gras In New Orleans" (Longhair).

While some of these early experiments were awkward fusions, it wasn't long before the Afro-Cuban elements were integrated into the New Orleans sound. Robert Palmer reports that, in the 1940s, Professor Longhair listened to and played with musicians from the islands and "fell under the spell of Pérez Prado's mambo records."[87] The Hawketts, in "Mardi Gras Mambo" (1954) (featuring the vocals of a young Art Neville), make a clear reference to Prado in their use of his trademark "Unhh!" in the break after the introduction.[88]

The "Bo Diddley beat" (1955) is perhaps the first true fusion of 3-2 clave and R&B/rock 'n' roll. Watch: "Hey Bo Diddley" performed live by Bo Diddley (1965). There is no documentation of a direct Cuban connection to Bo Diddley's adaptation of the clave rhythm. Bo Diddley has given different accounts of the riff's origins. However, Ned Sublette asserts: "In the context of the time, and especially those maracas [heard on the record], 'Bo Diddley' has to be understood as a Latin-tinged record. A rejected cut recorded at the same session was titled only 'Rhumba' on the track sheets."[89] Johnny Otis' "Willie and the Hand Jive" (1958) is another example of this successful blend of 3-2 clave and R&B. Watch: "Hand Jive" performed by Johnny Otis. The Johnny Otis Show. Otis used the Cuban instruments claves and maracas on the song. The song "Little Darling" is also built around clave. The bass riffs of "China Grove" by the Doobie Brothers use clave. The bass line in the 1973 arrangement of Herbie Hancock's "Watermelon Man" (from the album Head Hunters) is based on "son" clave. The Macarena uses clave. Another example includes the song "Not Fade Away," originally written by Buddy Holly, but performed by a number of artists including The Rolling Stones, The Grateful Dead, and Rush. In fact, there are hundreds of other examples throughout jazz and popular music.

Funk

The 2-3 clave onbeat/offbeat motif is the basis for a great deal of funk music. Blues scales give these rhythmic figures their own distinct quality. The main guitar riff for James Brown's "Bring it Up" is an example of an onbeat/offbeat motif. Rhythmically, the pattern is similar to the typical Cuban guajeo structure, but tonally, it is unmistakably funky.[90] Bongos are used on the 1967 version. The rhythm is slightly swung.

"Ain't it Funky" has a 2-3 guitar riff (c. late 1960s).

"Give it Up or Turn it Lose" (1969) has a similarly funky 2-3 structure. The tonal structure has a bare bones simplicity, emphasizing the pattern of attack-points.

Experimental clave music

Art music

The clave rhythm and clave concept have been used in some modern art music ("classical") compositions. "Rumba Clave" by Cuban percussion virtuoso Roberto Vizcaiño has been performed in recital halls around the world. See: "Rumba Clave" (Roberto Vizcaiño). Another clave-based composition that has "gone global" is the snare drum suite "Cross" by Eugene D. Novotney. See: "Cross" (Eugene Novotney).

Jazz

Ensemble clave-based rhythms translate well to a jazz drum kit. See: "Comping in Clave" by Conor Guilfoyle. The clave matrix offers infinite possibilities for rhythmic textures in jazz. The Cuban-born drummer Dafnis Prieto in particular, has been a trailblazer in expanding the parameters of clave experimentation. See: "Drum Solo with Displaced Clave" (Dafnis Prieto).

Odd meter "clave"

Technically speaking, the term odd meter clave is an oxymoron. Clave consists of two even halves, in a divisive structure of four main beats. However, in recent years jazz musicians from Cuba and outside of Cuba have been experimenting with creating new "claves" and related patterns in various odd meters. Clave which is traditionally used in a divisive rhythm structure, has inspired many new creative inventions in an additive rhythm context. See: "Songo with Clave in 9" (Conor Guilfoyle).

. . . I developed the concept of adjusting claves to other time signatures, with varying degrees of success. What became obvious to me quite quickly was that the closer I stuck to the general rules of clave the more natural the pattern sounded. Clave has a natural flow with certain tension and resolve points. I found if I kept these points in the new meters they could still flow seamlessly, allowing me to play longer phrases. It also gave me many reference points and reduced my reliance on "one"—Guilfoyle (2006: 10).[91]

Recommended listening for odd meter "clave."

Here are some examples of recordings that use odd meter clave concepts.[94]

- Dafnis Prieto About the Monks (Zoho).

- Sebastian Schunke Symbiosis (Pimienta Records).

- Paoli Mejias Mi Tambor (JMCD).

- John Benitez Descarga in New York (Khaeon).

- Deep Rumba A Calm in the Fire of Dances (American Clave).

- Nachito Herrera Bembe en mi casa (FS Music).

- Bobby Sanabria Quarteto Aché (Zoho).

- Julio Barretto Iyabo (3d).

- Michel Camilo Triangulo (Telarc).

- Samuel Torres Skin Tones (www.samueltorres.com).

- Horacio "el Negro" Hernandez Italuba (Universal Latino).

- Tony Lujan Tribute (Bella Records).

- Edward Simon La bikina (Mythology).

- Jorge Sylvester In the Ear of the Beholder (Jazz Magnet).

- Uli Geissendoerfer "The Extension" (CMO)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gerhard Kubik cited by Agawu, Kofi (2006: 1-46). “Structural Analysis or Cultural Analysis? Comparing Perspectives on the ‘Standard Pattern’ of West African Rhythm” Journal of the American Musicological Society v. 59, n. 1.

- ↑ Novotney, Eugene N. (1998: 165) Thesis: The 3:2 Relationship as the Foundation of Timelines in West African Musics, UnlockingClave.com. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois.

- ↑ Peñalosa, David (2012: 255) The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ↑ Gerstin, Julian (2013) "Rhythmic Structures in the African Continuum" Analytical Approaches to World Music.

- ↑ Agawu, Kofi (2003: 73) Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions. New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Nketia, Kwabena (1961: 78) African Music in Ghana. Accra: Longmans.

- ↑ Kubik, Gerhard (1999: 54) Africa and the Blues. Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-145-8.

- 1 2 3 Peñalosa, David (2009: 81). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ↑ "There are just two claves—son clave and rumba clave"— Berroa, Ignacio (1996: Warner Brothers VHS). Mastering the Art Afro-Cuban Drumming.

- ↑ Jones, A.M. (1959: 210, 212) Studies in African Music. London: Oxford University Press. 1978 edition: ISBN 0-19-713512-9.

- ↑ King, Anthony (1960: 51-52) “The Employment of the Standard Pattern in Yoruba Music” American Music Society Journal.

- ↑ Egblewogbe cited by Collins (2004: 29) African Musical Symbolism in Contemporary Perspective (Roots, Rhythms and Relativity) Berlin: Pro Business. ISBN 3-938262-15-X.

- ↑ C.K. Ladzekpo quoted by Peñalosa (2009: 244)

- ↑ "In reality, as Peñalosa explains in great detail in The Clave Matrix, there’s really only son and rumba clave, each of which can be played with a pure triple pulse structure feel, a pure duple pulse structure feel or somewhere in‐between. Needless to say, the terms son and rumba came much later." Moore, Kevin (2010: 72). Beyond Salsa Piano; The Cuban Timba Revolution. v. 3 Cuban Piano Tumbaos (1960-1979). Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com. ISBN 1-4505-4553-X

- ↑ Moore, Kevin (2010: 65) Beyond Salsa Piano; The Cuban Timba Revolution. v. 1 The Roots of the Piano Tumbao. Santa Cruz, CA: Kevin Moore. ISBN 978-1-4392-6584-0.

- ↑ Peñalosa (2009).

- ↑ Centro de Investigación de la Música Cubana (1997: 63) Instrumentos de la Música Folclórico-Popular de Cuba v. 1. Havana: CIDMUD. Recorded examples of "son clave" used in guaguancó: “Ultima rumba," Festival in Havana, Piñiero, Ignacio with Carlos Embale (1955: CD). “Ague que va caer,” Patato y Totico, Patato (1968: CD).

- ↑ Recorded examples of "son clave" used in yambú: “Ave Maria," Conjunto Folkloricó Nacional de Cuba, (1965: phonorecord).“Mama abuela,” Songs and Dances, Conjunto Clave y Guaguancó (1990: CD). “Maria Belen,” El callejon de los rumberos, Yoruba Andabo (1993: CD). “Chevere,” Déjala en la puntica, Conjunto Clave y Guaguancó (1996: CD). “Las lomas de Belén,” Buenavista en guaguagncó, Ecué Tumba (2001: CD).

- ↑ Santos, John (1986) “The Clave: Cornerstone of Cuban Music” Modern Drummer Magazine p. 32 Sept.

- 1 2 Grenet, Emilio, translated by R. Phillips (1939). Popular Cuban Music New York: Bourne Inc.

- ↑ Jones (1959: 3).

- 1 2 Locke, David (1982). "Principles of Off-Beat Timing and Cross-Rhythm in Southern Ewe Dance Drumming” Society for Ethnomusicology Journal Nov. 11.

- ↑ Peñalosa, David (2012: 248). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ↑ Toussaint, Godfried T. 2013 The Geometry of Musical Rhythm: What Makes a "Good" Rhythm Good? p. 17. ISBN 1-4665-1202-4

- ↑ Novotney, Eugene D. (1998). "Thesis: The 3:2 Relationship as the Foundation of Timelines in West African Musics".

- ↑ Toussaint, Godfried, “A Mathematical Analysis of African, Brazilian and Cuban Clave Rhythms” Montreal, School of Computer Science. Web.

- ↑ Toussaint, Godfried, "The Rhythm that Conquered the World: What Makes a 'Good' Rhythm Good?," Percussive Notes. Web.

- ↑ Toussaint, Godfried T. 2013 The Geometry of Musical Rhythm: What Makes a "Good" Rhythm Good? ISBN 1-4665-1202-4

- ↑ Toussaint, Godfried, “The Euclidean Algorithm Generates Traditional Musical Rhythms,” Proceedings of BRIDGES: Mathematical Connections in Art Music and Science p. 47 Banff.

- ↑ "The time span of the bell rhythm and its division into beats establish meter, a concept that implies a musical period" Locke, David "Improvisation in West African Musics" Music Educators Journal, Vol. 66, No. 5, (Jan., 1980), p. 125-133. Published by: MENC: The National Association for Music Education.

- ↑ "We find that all its melodic design is constructed on a rhythmic pattern of two measures, as though both were only one, the first is antecedent, strong, and the second is consequent, weak" Grenet, Emilio, translated by R. Phillips (1939). Popular Cuban Music New York: Bourne Inc.

- ↑ Mauleón, Rebeca (1999: 6) 101 Montunos. Petaluma, CA: Sher Publishing.

- ↑ [The] clave pattern has two opposing rhythm cells: the first cell consists of three strokes, or the rhythm cell, which is called tresillo (Spanish tres = three). This rhythmically syncopated part of the clave is called the three-side or the strong part of the clave. The second cell has two strokes and is called the two-side or the weak part of the clave. . . The different accent types in the melodic line typically encounter with the clave strokes, which have some special name. Some of the clave strokes are accented both in more traditional tambores batá -music and in more modern salsa styles. Because of the popularity of these strokes, some special terms have been used to identify them. The second stroke of the strong part of the clave is called bombo. It is the most often accented clave stroke in my research material. Accenting it clearly identifies the three-side of the clave (Peñalosa The Clave Matrix 2009, 93-94). The second common clave stroke accented among these improvisations is the third stroke of the strong part of the clave. This stroke is called ponche. In Cuban popular genres, this stroke is often accented in unison breaks that transition between the song sections (Peñalosa 2009, 95; Mauleón 1993, 169). The third typical way to accent the clave strokes is to play a rhythm cell, which includes both bombo and ponche accents. This rhythm cell is called [the] conga pattern (Ortiz, Fernando 1965 [1950] La Africania De La Musica Folklorica De Cuba, 277; Mauleón 1993, 169-170). Iivari, Ville (2011: 1, 5). The Relation Between Clave Pattern and Violin Improvisation in Santería’s Religious Feasts. Department of Musicology, University of Turku, Finland. Web. http://www.siba.fi/fi/web/embodimentofauthority/proceedings;jsessionid=07038526F10A06DE7ED190AD5B1744D7

- ↑ Amira and Cornelius (1992: 23, 24) The Music of Santeria; Traditional Rhythms of the Batá Drums. Tempe, AZ: White Cliffs. ISBN 0-941677-24-9

- ↑ Garrett, Charles Hiroshi (2008). Struggling to Define a Nation: American Music and the Twentieth Century, p.54. ISBN 978-0-520-25486-2. Shown in common time and then in cut time with tied sixteenth & eighth note rather than rest.

- ↑ Sublette, Ned (2007), Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo, p.134. ISBN 978-1-55652-632-9. Shown with tied sixteenth & eighth note rather than rest.

- ↑ "Rumba Clave: An Illustrated Analysis", Rumba Clave, BlogSpot. January 21, 2008. "One thing is certain: What you see in standard western notation as written-clave is a long way from what's actually played."

- ↑ Spiro, Michael (2006: 38). The Conga Drummer's Guidebook. Petaluma, CA: Sher Music Co.

- 1 2 Mauleón (1999: 49)

- 1 2 Amira and Cornelius (1992: 23)

- ↑ Jones, A.M. (1959: 211-212)

- ↑ Peñalosa (2009: 53)

- ↑ "Rumba Clave: An Illustrated Analysis", Rumba Clave, BlogSpot. January 21, 2008. "... as the tempo increased the clave would be played closer and closer to straight 12/8..."

- ↑ Santos (1986: 33)

- ↑ Thress, Dan (1994). Afro-Cuban Rhythms for Drumset, p.9. ISBN 0-89724-574-1.

- ↑ Curtis, Natalie (1920: 98)

- ↑ King, Anthony (1961:14). Yoruba Sacred Music from Ekiti. Ibadan University Press.

- ↑ Agawu, Kofi (2003). Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Novotney, Eugene D. (1998: 155). Thesis: The 3:2 Relationship as the Foundation of Timelines in West African Musics, UnlockingClave.com. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois.

- ↑ Novotney (1998: 250).

- ↑ Mauleón (1993: 47).

- ↑ Peñalosa (2009: 1-3).

- ↑ Kubik, Gerhard (2010: 78). Theory of African Music v. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Agawu, Kofi (2003: 73). Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Mauleón, Rebeca (1993: 52) Salsa Guidebook for Piano and Ensemble. Petaluma, California: Sher Music. ISBN 0-9614701-9-4.

- 1 2 Moore 2011 p. 32. Understanding Clave.

- ↑ Peñalosa 2010 p. 136. The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- 1 2 Bobby Sanabria quoted by Peñalosa (2009: 252).

- ↑ Peñalosa, David (2010: 154). The Clave Matrix.

- ↑ Moore, Kevin (2012: 28). Understanding Clave and Clave Changes: Singing, Clapping and Dancing Exercises. Santa Cruz: Moore Music. ISBN 1-4664-6230-2

- ↑ Mongo Santamaría, cited by Washburne, Christopher (2008: 190) Sounding Salsa; Performing Latin Music in New York City. Philadelphia: Temple University Press ISBN 1-59213-315-0.

- ↑ Mongo Santamaría, cited by Gerard, Charley (2001: 49) Music from Cuba: Mongo Santamaria, Chocolate Armenteros, and Other Stateside Cuban Musicians. Praeger Publishers.

- ↑ Sonny Bravo cited by Peñalosa (2009: 253).

- ↑ Alain Pérez cited by Peñalosa (2009: 253).

- ↑ Ortiz, Fernando (1950). La Africania De La Musica Folklorica De Cuba. Ediciones Universales, en español. Hardcover illustrated edition. ISBN 84-89750-18-1.

- ↑ Washburne, Christopher (1995). "Clave: The African Roots of Salsa" Kainda, Fall.http://www.chriswashburne.com/articles.html

- ↑ Curtis, Natalie (1920: 98). Songs and Tales from the Dark Continent. New York: Dover Press.

- ↑ Jones (1959: 212).

- ↑ Kofi, Francis (1997: 30, 42). Traditional Dance Rhythms of Ghana v.1. Everett, PA: Honey Rock.

- ↑ C.K. Ladzekpo cited by Peñalosa (2009: 244).

- ↑ Harington, Royal (1995: 63) West African Rhythms for Drumset. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred Publishing.

- ↑ Recorded examples of “son clave” in traditional music from Ghana and Benin: "Waka" (oge) Addy, Mustapha Tettey, The Royal Drums of Ghana (1991: CD). "Kpanlogo" and "Fumefume" Traditional Dance Rhythms of Ghana v.1, Kofi, Francis (1997: pp. 30, 42/CD). "Nago/Yoruba", Benin, Rhythms and Songs for the Vodun (1990: CD)

- ↑ Nigerian musician Segun Bucknor: "Latin American music and our music is virtually the same"—quoted by Collins 1992 p. 62

- ↑ Roberts, John Storm. Afro-Cuban Comes Home: The Birth and Growth of Congo Music. Original Music cassette tape (1986).

- ↑ After Banning Eyre (2006: 16). Africa: Your Passport to a New World of Music. Alfred Pub. ISBN 0-7390-2474-4

- ↑ After Banning Eyre (2006: 13).

- ↑ Eyre, Banning (2006: 9). "Highlife guitar example" Africa: Your Passport to a New World of Music. Alfred Pub. ISBN 0-7390-2474-4

- ↑ Peñalosa (2010: 247). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ↑ Graff, Folo (2001: 17). "Afrobeat" by Folo Graff. African Guitar Styles. Lawndale CA: ADG Productions.

- ↑ Recorded examples of “son clave” used in Brazilian Candomblé and Macumba rhythms: “Afro-Brazileiros” Batucada Fantastica v.4, Perrone, Luciano (1972: CD). “Avaninha / Vassi d'ogun” Musique du monde : Brésil Les eaux d'Oxala, (1982: CD). “Opanije” The Yoruba / Dahomean Collection, (1998: CD). “Popolougumde” Pontos de Macumba (1999: CD). Recorded example of “son clave” used in Brazilian maculule: “Maculule” Brazil Capoeira Pereira, Nazare (2003: CD).

- ↑ Bobby Sanabria cited by Peñalosa (2009: 243).

- ↑ Kubik (1999: 51).

- ↑ "Wynton Marsalis part 2." 60 Minutes. CBS News (26 Jun 2011).

- ↑ "[Afro]-Latin rhythms have been absorbed into black American styles far more consistently than into white popular music, despite Latin music's popularity among whites" (Roberts The Latin Tinge 1979: 41).

- ↑ Roberts, John Storm (1999: 16) Latin Jazz. New York: Schirmer Books.

- ↑ Peñalosa (2010: 174) The Clave Matrix.

- ↑ Palmer 1979 p. 14

- ↑ Stewart 2000) p. 307.

- ↑ Sublette, Ned (2007: 83). "The Kingsmen and the Cha-cha-chá." Ed. Eric Weisbard. Listen Again: A Momentary History of Pop Music. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-4041-0

- ↑ "John Storm Roberts cites many examples of Latin-tinged 1950s rhythm and blues, from artists such as Professor Longhair, Ruth Brown, Clyde McPhatter and Ray Charles. Roberts believes that R&B became a 'vehicle for the return of the Latin tinge to mass popular music'"—Stewart (2000: 295).

- ↑ Guilfoyle, Conor (2006: 10). Odd Meter Clave for Drumset; Expanding the Rhythmic Language of Cuba. Essen, Germany: Advance Music.

- ↑ Guilfoyle (2006: 58)

- ↑ Guilfoyle (2006: 41)

- ↑ discography compiled by Guilfoyle (2006: 71)

References

- Mauleón, Rebeca (1993). Salsa Guidebook for Piano and Ensemble. Petaluma, California: Sher Music. ISBN 0-9614701-9-4.

- Moore, Kevin (2012). Understanding Clave and Clave Changes: Singing, Clapping and Dancing Exercises. Santa Cruz: Moore Music. ISBN 978-1-4664-6230-4

- Ortiz, Fernando (1950). La Africania De La Musica Folklorica De Cuba. Ediciones Universales, en español. Hardcover illustrated edition. ISBN 84-89750-18-1.

- Palmer, Robert (1979). A Tale of Two Cities: Memphis Rock and New Orleans Roll .Brooklyn.

- Peñalosa, David (2009). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3

- Peñalosa, David (2010). Rumba Quinto. Redway, CA: Bembe Books. ISBN 1-4537-1313-1.

- Stewart, Alexander (2000). "Funky Drummer: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music." Popular Music, v. 19, n. 3. Oct., 2000), p. 293-318.

External links

- The Four Great Clave Debates

- Clave Concepts; Afro Cuban Rhythms

- An introduction to clave theory

- Clave Patterns

- Clave Changes in the Music of Charanga Habanera

- Clave Analysis of Charanga Habanera's Tremendo delirio

- Bossa Nova Clave

- Video about Bossa Nova Clave

- family of cuban clave patterns

- BBC World Service - Special Reports - A Short History of Five Notes