Solutrean

| |

| Geographical range | Western Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Epipaleolithic |

| Dates | c. 22,000 – c. 17,000 BP |

| Type site | Parc archéologique et botanique de Solutré |

| Preceded by | Gravettian |

| Followed by | Magdalenian |

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

|

↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

|

Lower Paleolithic

Middle Paleolithic

Upper Paleolithic

|

| ↓ Mesolithic ↓ Stone Age |

.jpg)

The Solutrean industry is a relatively advanced flint tool-making style of the Upper Palaeolithic, from around 22,000 to 17,000 BP.

Details

The term Solutrean comes from the type-site of "Crot du Charnier," dating to around 21,000 years ago and located at Solutré, in east-central France near Mâcon.

The Solutré site was discovered in 1866 by the French geologist and paleontologist Henry Testot-Ferry (second son of Napoleon's famous cavalryman, General Claude Testot-Ferry, Baron of the Empire). It is now preserved as the Parc archéologique et botanique de Solutré.

The industry was named by Gabriel de Mortillet to describe the second stage of his system of cave chronology, following the Mousterian, and he considered it synchronous with the third division of the Quaternary period. The era's finds include tools, ornamental beads, and bone pins as well as prehistoric art.

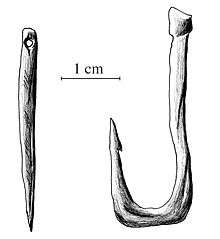

Solutrean tool-making employed techniques not seen before and not rediscovered for millennia. The Solutrean has relatively finely worked, bifacial points made with lithic reduction percussion and pressure flaking rather than cruder flintknapping. Knapping was done using antler batons, hardwood batons and soft stone hammers. This method permitted the working of delicate slivers of flint to make light projectiles and even elaborate barbed and tanged arrowheads. Large thin spearheads; scrapers with edge not on the side but on the end; flint knives and saws, but all still chipped, not ground or polished; long spear-points, with tang and shoulder on one side only, are also characteristic implements of this industry. Bone and antler were used as well.

The Solutrean may be seen as a transitory stage between the flint implements of the Mousterian and the bone implements of the Magdalenian epochs. Faunal finds include horse, reindeer, mammoth, cave lion, rhinoceros, bear and aurochs. Solutrean finds have been also made in the caves of Les Eyzies and Laugerie Haute, and in the Lower Beds of Creswell Crags in Derbyshire, England. The industry first appeared in what is now Spain, and disappears from the archaeological record around 17,000 BP.

Solutrean hypothesis in North American archaeology

The Solutrean hypothesis builds on similarities between the Solutrean industry and the later Clovis culture / Clovis points of North America, and suggests that people with Solutrean tool-technology crossed the Ice Age Atlantic by moving along the pack ice edge, using survival skills similar to those of modern Eskimo people. The migrants arrived in northeastern North America and served as the donor culture for what eventually developed into Clovis tool-making technology. Archaeologists Dennis Stanford and Bruce Bradley suggest that the Clovis point derived from the points of the Solutrean culture of southern France (19,000 BP) through the Cactus Hill points of Virginia (16,000 BP) to the Clovis point.[2][3] Stanford and Bradley also refer to other pre-Clovis finds in the Chesapeake Bay region of northeastern North America—such as the laurel-leaf Cinmar bifacial point—as possible links between Solutrean and Clovis lithic technology.[4] The idea of a Clovis-Solutrean link remains controversial and does not enjoy wide acceptance. The hypothesis is challenged by large gaps in time between the Clovis and Solutrean eras, a lack of evidence of Solutrean seafaring, lack of specific Solutrean features and tools in Clovis technology, the difficulties of the route and other issues.[5][6]

In 2014, the autosomal DNA of a male infant from a 12,500-year-old deposit in Montana was sequenced.[7] The DNA was taken from a skeleton referred to as Anzick-1. The skeleton was found in close association with several Clovis artifacts. Comparisons showed strong affinities with DNA from Siberian sites, and virtually ruled out any close affinity of Anzick-1 with European sources (see the "Solutrean hypothesis"). The DNA of the Anzick-1 sample showed strong affinities with sampled Native American populations, which indicated that the samples derive from an ancient population that lived in or near Siberia, the Upper Palaeolithic Mal'ta population.[8]

See also

| Preceded by Gravettian |

Solutrean 22,000–17,000 BP |

Succeeded by Magdalenian |

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ British Museum Highlights

- ↑ "Stone Age Columbus – programme summary". BBC. March 2004. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- ↑ The North Atlantic ice-edge corridor: a possible Palaeolithic route to the New World. Bruce Bradley and Dennis Stanford. World Archaeology 2004 Vol. 36(4): 459 – 478.

- ↑ Dennis Stanford, Darrin Lowery, Margaret Jodry, Bruce A. Bradley, Marvin Kay, Thomas W. Stafford and Robert J. Speakman. (2014) "New Evidence for a Possible Paleolithic Occupation of the Eastern North American Continental Shelf at the Last Glacial Maximum" Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf, pp 73–93

- ↑ Straus, L.G. (April 2000). "Solutrean settlement of North America? A review of reality". American Antiquity 65 (2): 219–226. doi:10.2307/2694056.

- ↑ Westley, Kieran and Justin Dix (2008). "The Solutrean Atlantic Hypothesis: A View from the Ocean". Journal of the North Atlantic 1: 85–98. doi:10.3721/J080527.

- ↑ Rasmussen M, Anzick SL, et al. (2014). "The genome of a Late Pleistocene human from a Clovis burial site in western Montana". Nature 506 (7487): 225–229. doi:10.1038/nature13025. PMID 24522598.

- ↑ "Ancient American's genome mapped". BBC News. 2014-02-14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Solutrean. |

- Clovis and Solutrean: Is There a Common Thread? by James M. Chandler

- Stone Age Columbus BBC TV programme summary

- "America's Stone Age Explorers" transcript of 2004 NOVA program on PBS

- Images of Solutrean artifacts

- Radical theory of first Americans places Stone Age Europeans in Delmarva 20,000 years ago Washington Post article from 28 February 2012

- Picture gallery of the Paleolithic (reconstructional palaeoethnology), Libor Balák at the Czech Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Archaeology in Brno, The Center for Paleolithic and Paleoethnological Research

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||