Social loafing

In social psychology, social loafing is the phenomenon of people exerting less effort to achieve a goal when they work in a group than when they work alone.[1][2] This is seen as one of the main reasons groups are sometimes less productive than the combined performance of their members working as individuals, but should be distinguished from the accidental coordination problems that groups sometimes experience.

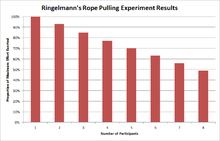

Social loafing can be explained by the "free-rider" theory and the resulting "sucker effect", which is an individual’s reduction in effort in order to avoid pulling the weight of a fellow group member.[3][4] Research on social loafing began with rope pulling experiments by Ringelmann, who found that members of a group tended to exert less effort in pulling a rope than did individuals alone. In more recent research, studies involving modern technology, such as online and distributed groups, have also shown clear evidence of social loafing. Many of the causes of social loafing stem from an individual feeling that his or her effort will not matter to the group.

History

Rope-pulling experiments

The first known research on the social loafing effect began in 1913 with Max Ringelmann's study. He found that when he asked a group of men to pull on a rope, that they did not pull as hard collectively as they did when each was pulling alone. This research did not distinguish whether this was the result of the individuals in a group putting in less effort or of poor coordination within the group.[5][6] In 1974, Alan Ingham and colleagues replicated Ringelmann's experiment using two types of group: 1) Groups with real participants in groups of various sizes (consistent with Ringelmann's setup) or 2) Pseudo-groups with only one real participant. In the pseudo-groups, the researchers' assistants only pretended to pull on the rope. The results showed a decrease in the participants' performance, with groups of participants who all exerted effort suffering the largest declines. Because the pseudo-groups were isolated from coordination effects (since the participant's confederates did not physically pull the rope), Ingham proved that communication alone did not account for the effort decrease, and that motivational losses were the more likely cause of the performance decline.[7]

Clapping and shouting experiments

In contrast with Ringelmann's first findings, Bibb Latané et al. replicated previous social loafing findings while demonstrating that the decreased performance of groups was attributable to reduced individual effort, as distinct from a deterioration due to coordination. They showed this by blindfolding male college students while making them wear headphones that masked all noise. They then asked them to shout both in actual groups and pseudogroups in which they shouted alone but believed they were shouting with others. When subjects believed one other person was shouting, they shouted 82% as intensely as they did alone, but with five others, their effort decreased to 74%.

Latané et al. concluded that increasing the number of people in a group diminished the relative social pressure on each person: "If the individual inputs are not identifiable the person may work less hard. Thus if the person is dividing up the work to be performed or the amount of reward he expects to receive, he will work less hard in groups."[8][9]

Meta-analysis study and the Collective Effort Model (CEM)

In a 1993 meta-analysis by Karau and Williams, they propose the Collective Effort Model (CEM), which is used to generate predictions.[1] The CEM integrates expectancy theories with theories of group-level social comparison and social identity to account for studies that examine individual effort in collective settings. From a psychological state, it proposes that Expectancy multiplied by Instrumentality multiplied by Valence of Outcome produces the resulting Motivational Force.

Karau et al.'s concluded that social loafing occurred because there was usually a stronger perceived contingency between individual effort and valued outcomes when working individually. When working collectively, other factors frequently determine performance, and valued outcomes are also divided among all group members. All individuals are assumed to try to maximize the expected utility of their actions. The CEM also acknowledges that some valued outcomes do not depend on performance. For example, exerting strong effort when working on intrinsically meaningful tasks or with highly respected team members may result in self-satisfaction or approval from the group, even if the high effort had little to no impact on tangible performance outcomes.[1]

Notable or novel findings by Karau and Williams following their implementation of the CEM include:

- The magnitude of social loafing is reduced for women and individuals originating from Eastern cultures.

- Individuals are more likely to loaf when their co-workers are expected to perform well.

- Individuals reduce social loafing when working with acquaintances and do not loaf at all when they work in highly valued groups.[1]

Dispersed versus collocated groups

A 2005 study by Laku Chidambaram and Lai Lai Tung based their research model on Latané’s social impact theory, and hypothesized that as group size and dispersion grew, the group’s work would be affected in the following areas: Members would contribute less in both quantity and quality, final group output would be of lower quality, and a group’s output would be affected both by individual factors and contextual factors.

A sample of 240 undergraduate business students was randomly split into forty teams (half of the teams were 4-person and half 8-person) which were randomly assigned to either a collocated or distributed setting. The participants were to complete a task that asked them to act as a board of directors of a winery with an image problem. They were to find and discuss alternatives, and at the end submit their alternative with rationale. Collocated groups worked at a table together, while distributed groups did the same task at separate computers that allowed for electronic, networked communication. The same technology was used by both collocated and distributed groups.

Chidambaram and Tung found that group size mattered immensely in a group’s performance. The smaller the group, the more likely each member was to participate, regardless of range (dispersed or collocated). The main difference stated between distributed and collocated groups was the social pressure at least to appear busy that is present in collocated groups. When others are present, people feel the need to look as if they are working hard, while those who are not in the presence of others do not.[10]

Effect of culture

In 1989, Christopher P. Earley hypothesized that social loafing would be mitigated in collectivist cultures that focused more on achievement of the group than the individual. He conducted a study in the United States and China, two polar opposites in terms of culture (with the U.S. being individualistic and China being collectivist), in order to determine if a difference in social loafing was present between the two types of cultures. Earley formed groups from both countries similar in demographics and in time spent with each other (participants in each of the groups had known each other for three to five weeks). Each group was tasked with completing various forms of paperwork similar to work they would be required to do in their profession. The paperwork was designed to take two to five minutes for each item, and the items were turned in to an assistant when completed so that no one could judge their work compared to others. Each participant was given 60 minutes to complete as many items as possible and was separated into either the high-accountability group, where they were told they needed to achieve a group goal, or a low-accountability group, where they were told they were to achieve a goal alone. They were also separated into high and low shared responsibility groups. It was found that, consistent with other studies, highly individualistic people performed more poorly on the task when there was high shared responsibility and low accountability than when there was high accountability. The collectivists, however, performed somewhat better on the task when high shared responsibility was present, regardless of how accountable they were supposed to be as compared to when they were working alone. This evidence suggests that collectivist thinking reduces the social loafing effect. Further evidence from a similar study showed the effect was related to the collectivist thinking rather than nationality, as individualistic Chinese workers did indeed show a social loafing effect.[11]

Causes

Diffusion of responsibility/Evaluation potential

As the number of people in the group or team increase, people tend to feel deindividuation. This term defines both the dissociation from individual achievement and the decrease of personal accountability, resulting in lower exerted effort for individuals in collaborative environments. This phenomenon can thus decrease overall group effectiveness because it is contagious and hard to correct. Once identified by the group or team leader, it is their responsibility to reassess and put into motion new rules and expectations for everyone.

People could simply feel "lost in the crowd", so they feel that their effort would not be rewarded even if they put it forth. This idea can also cause people to feel as though they can simply "hide in the crowd" and avoid the averse effects of not applying themselves.[8]

When enthusiasm for the overall goal or task is diminished, overall contribution will drop. When one feels that their overall efforts are reduced or unimportant, they will likely become social loafers.

Motivation

Social psychological literature has found that the level of motivation one has to engage in an activity influences one’s behavior in a group setting. This finding, deemed the collective effort model by Karau and Williams (1993, 2001) details that individuals who are more motivated are more likely to engage in social facilitation (that is, to increase one’s efforts when in the presence of others) whereas those who are less motivated are more likely to engage in social loafing.[12] Researchers have determined that two factors which determine an individual’s motivation, and subsequently whether or not the individual will resort to social loafing versus social facilitation, include the individual’s expectations about attaining the goal and the perceived value of the goal.

Thus, a person’s attitude toward these two factors will influence his or her motivation level and subsequent group behavior. Karau and Williams (1993, 2001) found that motivation was highest when the individual believed that the goal was easily attainable and very valuable. On the other hand, motivation was lowest when the goal seemed impossible and not at all valuable.[12]

Unfortunately, the presence of a group can influence one’s perception of these two factors in a number of ways. For instance, working in a group may reduce or increase one’s expectancy of attaining a goal. That is, depending on the qualities of the group members, an individual may find themselves in a group of high achievers who work hard and are guaranteed success, whereas another may equally find themselves in a group of lazy or distracted people, making success seem unattainable. Therefore, the link between one’s personal efforts and success is not direct, as our success is influenced by the work of others. Similarly, the value of the goal may be contingent on the group members. For instance, if we must share the reaping of success with all other group members, then the value of the goal is reduced compared to the value of the goal from an individual perspective. Hence, the dynamic of the group is an important key in determining a person’s motivation and the likelihood of social loafing.[12] Additional factors which have been found to influence the likelihood of social loafing include one’s gender, one’s cultural background and the complexity of the task.

Dispensability of effort

When a group member does not feel that his/her effort is justified in the context of the overall group, the individual will be less willing to assert the effort. If the group size is large, members can feel that their contribution will not be worth much to the overall cause because so many other contributions can or should occur. This leads people to not contribute as much or at all in large groups as they might have in smaller groups.

One example is voting in the United States. Even though most people say that voting is important, and a good practice for them to do, every year a sub-optimal percentage of Americans turn up to vote, especially in presidential elections (only 51% in the 2000 election).[13] One vote may feel very small in a group of millions, so people may not think a vote is worth the time and effort. If too many people think this way, there is a small percentage of voter turnout. Some countries enforce compulsory voting to reduce this effect.

"Sucker" effect/Aversion

People feel that others in the group will leave them to do all the work while they take the credit. Because people do not want to feel like the "sucker," they wait to see how much effort others will put into a group before they put any in. If all the members try to avoid being the sucker, then everyone's effort will be significantly less than it would be if all of them were working as hard as they could.[14]

For example, in a workplace environment, the establishment of an absence culture creates an attitude that all employees deserve to have a certain number of days of absence, regardless of whether or not they are actually sick. Therefore, if an employee has not used the maximum number of absence days, "he may feel that he is carrying an unfair share of the workload".[4]

Attribution and equity/Matching of effort

Jackson and Williams (1985) proposed that if someone feels that others in the group are slacking or that others will slack, he will lower his effort to match that of the others. This can occur whether it is apparent that the others are slacking or if someone simply believes that the group is slacking.[1][15] For example, in the Latane et al. study above, if a participant heard the others making less noise than anticipated, he could have lowered his effort in an attempt to equal that of the others, rather than aiming for the optimum.[8]

Submaximal goal setting

By setting a goal that is based on maximization, people may feel that there is a set level that the group needs to be achieved. Because of this, they feel that they can work less hard for the overall desired effect.

For example, in the Latane et al. clapping and shouting study, people who were alone but told that they were part of a group screaming or clapping could have thought that there was a set level of noise that experimenters were looking for, and so assumed they could work less hard to achieve this level depending on the size of the group.[8]

Real-life instances

1994 Black Hawk shootdown incident

On April 14, 1994, two U.S. Air Force F-15 fighters accidentally shot down two U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopters over Northern Iraq, killing all 26 soldiers on board. The details of the incident have been analyzed by West Point Professor Scott Snook in his book Friendly Fire.[16] In his summary of the fallacy of social redundancy, Snook points to social loafing as a contributor to the failure of the AWACS aircraft team to track the helicopters and prevent the shootdown. Snook asserts that responsibility was "spread so thin by the laws of social impact and confused authority relationships that no one felt compelled to act".[16]

Social loafing and the workplace

According to Hwee Hoon Tan and Min-Li Tan, social loafing is an important area of interest in order to understand group work.[17] While the opposite of social loafing, "organizational citizenship behavior", can create significant productivity increases, both of these behaviors can significantly impact the performance of organizations. Social loafing is a behavior that organizations want to eliminate. Understanding how and why people become social loafers is critical to the effective functioning, competitiveness and effectiveness of an organization.

There are certain examples of social loafing in the workplace that are discussed by James Larsen in his essay "Loafing on The Job." For example, Construction men working vigorously on a construction site while some of their working partners are lounging on rock walls or leaning on their shovels doing nothing. Another example is a restaurant such as McDonald's where some employees are lounging about while others are eagerly ready to take an order. These scenarios all express the problems that social loafing creates in a workplace, and businesses would like to find a way to counteract these trends.

Larsen mentions ways that a business could change its operations in order to fight the negative effects of social loafing. For one, research has shown that if each employee has their performance individually measured, they will put in more effort than if it was not measured. Another person interested in the idea of social loafing is Kenneth Price, from The University of Texas. Price conducted a social loafing experiment in order to examine whether two key factors that he suspected played a role in the way social loafing arose in work groups. These two factors were dispensability and fairness. The experiment that he conducted involved 514 people that were divided into 144 teams that were set to meet for fourteen weeks. The projects assigned to these people were very complex and called for diverse skills from many different individuals in order to be fully completed. The experiments findings did in fact corroborate Price's suspicions in the two factors of dispensability and fairness.

Dispensability in a group is described by Price as employees who join a work group and quickly begin to measure up their skills with the people that they are assigned to work with. If they feel that their skills are inferior to those around them, people tend to sit back and let the other more skilled workers carry the workload. Fairness in a group is when some group members feel that their voice is not heard in decision making because of their ethnicity, gender or other discriminatory factors. Instead of fighting for their voice to be heard many group members will decide to loaf in these circumstances.

Online communities and groups

Research regarding social loafing online is currently relatively sparse, but is growing.[3]

A 2008 study of 227 undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in web-enabled courses at the Naval War College (NWC) and a public university found that social loafing not only exists, but may also be prevalent in the online learning classroom. Although only 2% of NWC and 8% of public university students self-reported social loafing, 8% of NWC and 77% of public university students indicated the perception of others engaging in social loafing. Additional findings generally verify face-to-face social loafing findings from previous studies. The researchers conclude that injustice in the distribution of rewards increases social loafing, and suggest that self-perceived dominance negatively affects individual participation in group activities.[3]

Social loafing, also known as "lurking", greatly affect the development and growth of online communities. The term social loafing refers to the tendency for individuals to expend less effort when working collectively than when working individually.[1] This phenomenon is much like people’s tendency to be part of a group project, but rely heavily on just a few individuals to complete the work. Generally, social loafers regularly follow the discussions and content of online communities, but choose not to expand on posts or add to the knowledge of the community.[18] Additionally, participation in online communities is usually voluntary; therefore there is no guarantee that community members will contribute to the knowledge of the website, discussion forum, bulletin board, or other form of online engagement.

Lurkers are reported to constitute over 90% of several online groups.[1]

The main reason people choose not to contribute to online communities surprisingly does not have to do with societal laziness, but in fact the potential contributors belief that their entries will not be taken seriously or given the credit that they deserve. When people assess the risks involved in contributing to online communities, they generally avoid participation because of the uncertainty of who the other contributors and readers are and the fear of their work being undervalued.[18]

Age-related effects on participation

Although studies justify the notion that people often do not contribute to online communities, some research shows that older adults are actually more likely to participate in online communities than younger people because different generations tend to use the internet differently. For example, "older adults are more likely to seek health information, make purchases, and obtain religious information, but less likely to watch videos, download music, play games, and read blogs online".[19] This is perhaps due in part to the fact that some online communities cater to older generations. The content of the website often determines what age group will use or visit the site, and because many forms of online communities appear on sites that focus their attention on older adults, participation is generally higher. Additionally, the ease and availability of operating the websites that host the online community may play a role in the age group that is most likely to participate. For example, some online communities geared toward older adults have simplified the design of their sites in order to enhance their look and usability for older adults.[19]

Reducing social loafing

According to Dan J. Rothwell, it takes "the three Cs of motivation" to get a group moving: collaboration, content, and choice.[20] Thus, the answer to social loafing may be motivation. A competitive environment may not necessarily get group members motivated.

- Collaboration is a way to get everyone involved in the group by assigning each member special, meaningful tasks.[21] It is a way for the group members to share the knowledge and the tasks to be fulfilled unfailingly. For example, if Sally and Paul were loafing because they were not given specific tasks, then giving Paul the note taker duty and Sally the brainstorming duty will make them feel essential to the group. Sally and Paul will be less likely to want to let the group down, because they have specific obligations to complete.

- Content identifies the importance of the individual's specific tasks within the group. If group members see their role as that involved in completing a worthy task, then they are more likely to fulfill it. For example, Sally may enjoy brainstorming, as she knows that she will bring a lot to the group if she fulfills this obligation. She feels that her obligation will be valued by the group.

- Choice gives the group members the opportunity to choose the task they want to fulfill. Assigning roles in a group causes complaints and frustration. Allowing group members the freedom to choose their role makes social loafing less significant, and encourages the members to work together as a team.

Thompson stresses that ability and motivation are essential, but insufficient for effective team functioning. A team must also coordinate the skills, efforts, and actions of its members in order to effectively achieve its goal. Thompson's recommendations can be separated into motivation strategies and coordination strategies:[22]

| Motivation strategies | Coordination strategies |

|---|---|

|

|

Motivational strategies

Increase identifiability: Studies of social loafing suggest that people are less productive when they are working with others, but social facilitation studies have shown that people are more productive when others are present (at least with an easy task). If individuals within a group know one another, feel that their productivity or inputs are not identifiable, then social loafing is likely to occur. Alternatively, if individuals are anonymous and therefore unidentifiable, then social loafing may also be likely to occur.[23]

Minimize free riding: Free riding occurs when members do less than their share of the work because others will make up for their slack. As others contribute ideas, individuals may feel less motivated to work hard themselves. They see their own contributions as less necessary or less likely to have much impact.[24] To eliminate these effects, it is important to make group members feel that their contributions are essential for the group’s success. Additionally, it is less likely for someone to free-ride if they are in a small group.[23]

Promote involvement: Loafing is also less likely to occur when people are involved with their work, and when they enjoy working with others in groups. These are people who value both the experience of being part of a group, as well as achieving results. Also, challenging and difficult tasks reduce social loafing. Social loafing is also reduced when individuals are involved in group work and their rewards are received as a team, rather than individually.[23]

Strengthen team cohesion: The extent to which group members identify with their group also determines the amount of social loafing. This concept links with social identity theory in that that difference between a hard-working group and one that is loafing is the match between the group’s tasks and its members’ self definitions. When individuals derive their sense of self and identity from their membership, social loafing is replaced by social laboring (members will expand extra effort for their group).[23]

Set goals: Groups that set clear, challenging goals outperform groups whose members have lost sight of their objectives. The group's goals should be relatively challenging, instead of being too easily accomplished. The advantages of working in a group are often lost when a task is so easy that it can be accomplished even when members of the group socially loaf. Thus, groups should ensure to set their standards high, but not so high that the goals are unattainable. Latham and Baldes (1975) assessed the practical significance of Locke's theory of goal setting by conducting an experiment with truck drivers who hauled logs from the woods to the mill. When the men were initially told to do their best when loading the logs, they carried only about 60% of the weight that they could legally haul. When the same drivers were later encouraged to reach a goal of hauling 94% of the legal limit, they increased their efficiency and met this specific goal. Thus, the results of this study show that performance improved immediately upon the assignment of a specific, challenging goal. Company cost accounting procedures indicated that this same increase in performance without goal setting would have required an expenditure of a quarter of a million dollars on the purchase of additional trucks alone. So this method of goal setting is extremely effective.[25] Other research has found that clear goals can stimulate a number of other performance-enhancing processes, including increases in effort, better planning, more accurate monitoring of the quality of the groups work, and even an increased commitment to the group.[26]

Individual Assessment In order to reduce social loafing, a company can always focus on assessing each members contribution rather than only examining the teams accomplishments as a whole. It is statistically proven that social loafers will tend to put in less effort because of the lack of no external or internal assessment of their contributions. This leads to less self-awareness in the group because the team together is the only body evaluated. (Curt. 2007)

Encouraging contributions in online communities

Piezon & Donaldson argue in a 2005 analysis that special attention should be paid to the physical separation, social isolation, and temporal distance associated with distance education courses, which may induce social loafing. In terms of group size, they assert that there is no significant gain in small groups larger than six unless the group is brainstorming, and that the optimal group size may be five members. Suggestions that they have for online groups include clarifying roles and responsibilities, providing performance data for comparison with other groups, and mandating high levels of participation consisting of attending group meetings, using the discussion board, and participating in chats.[27]

In a 2010 analysis of online communities, Kraut and Resnick suggest several ways to elicit contributions from users:[28]

- Simply asking users, either implicitly through selective presentation of tasks or explicitly through requests that play on the principles of persuasion

- Changing the composition or activity of the group

- Using a record-keeping system to reflect member contributions, in addition to awarding privileges or more tangible awards

An example that the authors study is Wikipedia, which runs fundraising campaigns that involve tens of thousands of people and raise millions of dollars by employing large banner ads at the top of the page with deadlines, specific amounts of money set as the goal, and lists of contributors.

Reduction in group projects

In 2008, Praveen Aggarwal and Connie O'Brien studied several hundred college students assessing what factors can reduce social loafing during group projects. From the results, they concluded that there were three factors that reduce social loafing.[29]

Limiting the scope of the project: Instructors can reduce social loafing by either dividing a big project into two or more smaller components or replacing semester-long projects with a smaller project and some other graded work. Also, breaking up a big project into smaller components can be beneficial.[29]

Smaller group size: Limiting the group size can make it harder for social loafers to hide behind the shield of anonymity provided by a large group. In smaller groups, each member will feel that their contribution will add greater value.[29]

Peer evaluations: Peer evaluations send a signal to group members that there will be consequences for non-participation. It has been found that as the number of peer evaluations during a project go up, the incidence of social loafing goes down.[29]

See also

- Adaptive performance

- Audience effect

- Bystander effect

- Collective responsibility

- Diffusion of responsibility

- Ringelmann effect

- Social compensation

- Social facilitation

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Karau, Steven J.; Williams, Kipling D. (1993). "Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65 (4): 681–706. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.681. ISSN 0022-3514.

the reduction in motivation and effort when individuals work collectively compared with when they work individually or coactively

- ↑ Gilovich, Thomas; Keltner, Dacher; Nisbett, Richard E. (2006). Social psychology. W.W. Norton. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-393-97875-9.

The tendency to exert less effort when working on a group task in which individual contributions cannot be measured

- 1 2 3 Piezon, Sherry L., and Ferree, William D. "Perceptions of Social Loafing in Online Learning Groups: A study of Public University and U.S. Naval War College students." June 2008. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. 9 (2)

- 1 2 Krumm, Diane J. (December 2000). Psychology at work: an introduction to industrial/organizational psychology. Macmillan. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-57259-659-7. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ Ringelmann, M. (1913) "Recherches sur les moteurs animés: Travail de l'homme" [Research on animate sources of power: The work of man], Annales de l'Institut National Agronomique, 2nd series, vol. 12, pages 1-40.

- ↑ Kravitz, David A.; Martin, Barbara (1986). "Ringelmann rediscovered: The original article". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50 (5): 936–9441. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.936. ISSN 1939-1315.

- ↑ Ingham, Alan G.; Levinger, George; Graves, James; Peckham, Vaughn (1974). "The Ringelmann effect: Studies of group size and group performance". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 10 (4): 371–384. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(74)90033-X. ISSN 0022-1031.

- 1 2 3 4 Latané, Bibb; Williams, Kipling; Harkins, Stephen (1979). "Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37 (6): 822–832. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.6.822. ISSN 0022-3514.

- ↑ PsyBlog "Social Loafing: when groups are bad for productivity," 29 May 2009 (citing, inter alia, Latane).

- ↑ Chidambaram, Laku; Tung, Lai Lai (2005). "Is Out of Sight, Out of Mind? An Empirical Study of Social Loafing in Technology-Supported Groups". Information Systems Research 16 (2): 149–168. doi:10.1287/isre.1050.0051. ISSN 1047-7047.

- ↑ Christopher Earley, P. (1989). "Social Loafing and Collectivism: A Comparison of the United States and the People's Republic of China". Administrative Science Quarterly 34 (4): 565–581. doi:10.2307/2393567.

- 1 2 3 Forsyth, D. R. (2009). Group dynamics: New York: Wadsworth. [Chapter 10]

- ↑ Edwards, Wattenberg, Lineberry (2005). Government in America: People, Politics, and Policy, 12/E (Chapter 6 summary).

- ↑ Thompson, L. L. (2003). Making the team: A guide for managers. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. (pp. 31-32).

- ↑ Jackson, J. M. & Harkins, S. G. (1985). Equity in effort: An explanation of the social loafing effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 1199-1206.

- 1 2 Snook, Scott A. (2000). Friendly Fire: The Accidental Shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-691-09518-9

- ↑ Hoon, Hwee; Tan, Tan Min Li (2008). "Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Social Loafing: The Role of Personality, Motives, and Contextual Factors". The Journal of Psychology 142 (1): 89–108. doi:10.3200/JRLP.142.1.89-112. ISSN 0022-3980.

- 1 2 Shiue, Yih-Chearng; Chiu, Chao-Min; Chang, Chen-Chi (2010). "Exploring and mitigating social loafing in online communities". Computers and Human Behavior 26 (4): 768–777. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.01.014. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- 1 2 Chung, Jae Eun; Park, Namkee; Wang, Hua; Fulk, Janet; McLaughlin, Maraget (2010). "Age differences in perceptions of online community participation among non-users: An extension of the Technology Acceptance Model". Computers in Human Behavior 26 (6): 1674–1684. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.016. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ Rothwell, J. Dan (27 December 1999). In the Company of Others: An Introduction to Communication. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1-55934-738-9. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ "Pattern: Collaboration in Small Groups" by CSCW, The Computing Company, October 31, 2005, retrieved October 31, 2005

- ↑ Thompson, L. L. (2003). Making the team: A guide for managers. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. (pp. 29-36).

- 1 2 3 4 Forsythe, 2010.

- ↑ Kassin, Saul; Fein, Steven; Markus, Hazel Rose. Social psychology (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Wadsworth. p. 312. ISBN 978-0495812401.

- ↑ Latham, Gary, P.; Baldes (1975). "James, J.". Journal of Applied Psychology 60 (1). doi:10.1037/h0076354.

- ↑ Weldon, E.; Jehn (1991). "K.". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61 (4). doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.555.

- ↑ Piezon, S. L. & Donaldson, R. L. "Online groups and social loafing: Understanding student-group interactions." 2005. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 8(4).

- ↑ Kraut, R. E., & Resnick, P. Encouraging online contributions. The science of social design: Mining the social sciences to build successful online communities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 Aggarwal, P., & O’Brien, C. (2008). Social loafing on group projects: Structural antecedents and effect on student satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Education, 30(3), 25-264.

Further reading

- Forsyth, D.R. (2010). Group Dynamics (5th edition). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Jackson, J. M. & Williams, K. D. (1985). Social loafing on difficult tasks. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 937-942.

- Rothwell, J, D. In the Company of Others, McGraw-Hill, 2004, ISBN 0-7674-3009-3.

- Rothwell, Dan J., In Mixed Company: Communicating in Small Groups, 3rd. ed., Harcourt Brace College Publishers, Orlando, p. 83.

- "Pattern: Collaboration in Small Groups" by CSCW, The Computing Company, October 31, 2005, retrieved October 31, 2005.

External links

| The Wikibook Managing Groups and Teams has a page on the topic of: Social Loafing |