Smelling salts

Smelling salts, also known as ammonia inhalants, spirit of hartshorn or sal volatile, are chemical compounds used for arousing consciousness.

Usage

The usual active compound is ammonium carbonate, a colorless-to-white, crystalline solid ((NH4)2CO3).[1] Because most modern solutions are mixed with water, they should more properly be called "aromatic spirits of ammonia."[1] Modern solutions may also contain other products to perfume or act in conjunction with the ammonia, such as lavender oil or eucalyptus oil.[2]

Historically, smelling salts have been used on people feeling faint,[3][4][5] or who have fainted. They are typically administered by others, but may be self-administered; some at-risk groups, such as pregnant women, may be advised to keep them close to hand.[6]

Smelling salts are often used on athletes (particularly boxers) who have been dazed or knocked unconscious to restore consciousness and mental alertness. Smelling salts are now banned in most Boxing competitions.[1]

They are also used as a form of stimulant in athletic competitions (such as powerlifting, strong man and ice hockey) to "wake up" competitors to perform better.[1][7] Athletes such as Phil Kessel, Alexander Ovechkin, Tyler Seguin, Sean Monahan, Derick Brassard, Keith Kinkaid, Ilya Kovalchuk, Brett Favre, Peyton Manning, Carlos Boozer, Samuel Eto'o, David Desharnais, Greg Hardy, Johnny Gaudreau and Tom Brady have been seen using smelling salts on the sidelines.[8][9][10][11]

History

Smelling salts have been used since Roman times and are mentioned in the writings of Pliny as Hammoniacus sal.[1] Evidence exists of use in the 13th century by alchemists as sal ammoniac.[1] In the 17th century, the distillation of an ammonia solution from shavings of harts' (deer) horns and hooves led to the alternative name for smelling salts as spirit or salt of hartshorn.[1]

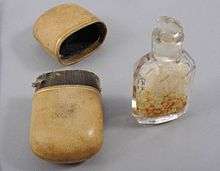

They were widely used in Victorian Britain to revive fainting women, and in some areas constables would carry a container of them for the purpose.[12] During this time, smelling salts were commonly dissolved with perfume in vinegar or alcohol and soaked onto a sponge, which was then carried on the person in a decorative container called a vinaigrette.[13]

The use of smelling salts was widely recommended during the Second World War, with all workplaces advised by the British Red Cross and St. John Ambulance to keep smelling salts in their first aid boxes.[14]

Physiological action

Smelling salts release ammonia (NH3) gas, which triggers an inhalation reflex (that is, cause the muscles that control breathing to work faster[7]) by irritating the mucous membranes of the nose and lungs.[7] Additionally, the irritant elevates the heart rate, blood pressure, and brain activity by activating the sympathetic nervous system. Fainting can be caused by excessive parasympathetic and vagal activity that slows the heart, and decreases perfusion of the brain.[15] The sympathetic irritant effect is exploited to counteract these vagal parasympathetic effects and thereby reverse the faint.[16]

Risks

Ammonia gas is toxic in large concentrations for prolonged periods and can be fatal.[1][5] Since smelling salts produce only a small amount of ammonia gas, no adverse health problems from their situational use have been reported.[1] However, a high concentration of inhaled ammonia might burn the nasal or oral mucosa.[1]

The use of ammonia smelling salts to revive people injured during sport is not recommended because it may inhibit or delay a proper and thorough neurological assessment by a healthcare professional,[1] such as after concussions when hospitalization may be advisable, and some governing bodies recommend specifically against it.[17] The irritant nature of smelling salts means that they can exacerbate any pre-existing cervical spine injury by causing reflex withdrawal away from them.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 McCrory, J (2006). "Smelling Salts". British Journal of Sport Medicine 40 (8): 659–660. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.029710. PMC 2579444. PMID 16864561. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "Mackenzies Smelling Salts". Electronic Medicines Compendium. March 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Boyd-McLaughlin, Kathy. "How not to faint at the altar". USA Bride. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ "Compact Oxford English Dictionary - Smelling Salts". Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Prof. Shakhashiri (2008-02-01). "Chemical of the week - Ammonia" (PDF). University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ "Common ailments during pregnancy". Baby Guide UK. Archived from the original on 2002-04-24.

- 1 2 3 "Henman's smelling salt solution". BBC News. 2002-07-02. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Freeman, Mike. "A whiff of TROUBLE?". The Times-Union. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- ↑ Ulman, Howard (2012-10-07). "NFL: Tom Brady outduels Peyton Manning". Toronto: The Associated Press. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- ↑ Goldschein, Eric. "Today On ESPN’s Wired Segment: Russell Westbrook Sings Nicki Minaj, Carlos Boozer Doesn’t Like It". Sports Grind. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- ↑ MONKOVIC, TONI (2011-01-18). "Tom Brady Says He Was Sniffing Ammonia". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-1-21. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Antique gadgets". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "“Bad Smells” and “Fragrance”: Reading Mansfield Park through the Eighteenth-Century Nose". Jane Austen Society of North America.

- ↑ "Air Raids fact sheet: First aid kits". Caring on the home front.

- ↑ "Fainting," WebMD, Updated Jan. 2, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Why do smelling salts wake you up?". 7 Jul 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ↑ "Pitchside medical care". The Football Association.