Comma category

In mathematics, a comma category (a special case being a slice category) is a construction in category theory. It provides another way of looking at morphisms: instead of simply relating objects of a category to one another, morphisms become objects in their own right. This notion was introduced in 1963 by F. W. Lawvere (Lawvere, 1963 p. 36), although the technique did not become generally known until many years later. Several mathematical concepts can be treated as comma categories. Comma categories also guarantee the existence of some limits and colimits. The name comes from the notation originally used by Lawvere, which involved the comma punctuation mark. Although standard notation has changed since the use of a comma as an operator is potentially confusing, and even Lawvere dislikes the uninformative term "comma category" (Lawvere, 1963 p. 13), the name persists.

Definition

The most general comma category construction involves two functors with the same codomain. Often one of these will have domain 1 (the one-object one-morphism category). Some accounts of category theory consider only these special cases, but the term comma category is actually much more general.

General form

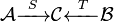

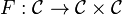

Suppose that  ,

,  , and

, and  are categories, and

are categories, and  and

and  (for source and target) are functors

(for source and target) are functors

We can form the comma category  as follows:

as follows:

- The objects are all triples

with

with  an object in

an object in  ,

,  an object in

an object in  , and

, and  a morphism in

a morphism in  .

. - The morphisms from

to

to  are all pairs

are all pairs  where

where  and

and  are morphisms in

are morphisms in  and

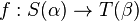

and  respectively, such that the following diagram commutes:

respectively, such that the following diagram commutes:

![\begin{matrix} S(\alpha) & \xrightarrow{S(g)} & S(\alpha')\\ f \Bigg\downarrow & & \Bigg\downarrow f'\\ T(\beta) & \xrightarrow[T(h)]{} & T(\beta') \end{matrix}](../I/m/7bc89af5b85528ffdf4c0b82eba216ad.png)

Morphisms are composed by taking  to be

to be  , whenever the latter expression is defined. The identity morphism on an object

, whenever the latter expression is defined. The identity morphism on an object  is

is  .

.

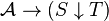

Slice category

The first special case occurs when  ,

,  is the identity functor, and

is the identity functor, and  (the category with one object

(the category with one object  and one morphism). Then

and one morphism). Then  for some object

for some object  in

in  . In this case, the comma category is written

. In this case, the comma category is written  , and is often called the slice category over

, and is often called the slice category over  or the category of objects over

or the category of objects over  . The objects

. The objects  can be simplified to pairs

can be simplified to pairs  , where

, where  . Sometimes,

. Sometimes,  is denoted

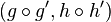

is denoted  . A morphism from

. A morphism from  to

to  in the slice category is then an arrow

in the slice category is then an arrow  making the following diagram commute:

making the following diagram commute:

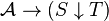

Coslice category

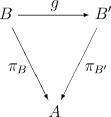

The dual concept to a slice category is a coslice category. Here,  has domain 1 and

has domain 1 and  is an identity functor. In this case, the comma category is often written

is an identity functor. In this case, the comma category is often written

, where

, where  is the object of

is the object of  selected by

selected by  . It is called the coslice category with respect to

. It is called the coslice category with respect to  , or the category of objects under

, or the category of objects under  . The objects are pairs

. The objects are pairs  with

with  . Given

. Given  and

and  , a morphism in the coslice category is a map

, a morphism in the coslice category is a map  making the following diagram commute:

making the following diagram commute:

Arrow category

and

and  are identity functors on

are identity functors on  (so

(so  ). In this case, the comma category is the arrow category

). In this case, the comma category is the arrow category  . Its objects are the morphisms of

. Its objects are the morphisms of  , and its morphisms are commuting squares in

, and its morphisms are commuting squares in  .[1]

.[1]

Other variations

In the case of the slice or coslice category, the identity functor may be replaced with some other functor; this yields a family of categories particularly useful in the study of adjoint functors. For example, if  is the forgetful functor mapping an abelian group to its underlying set, and

is the forgetful functor mapping an abelian group to its underlying set, and  is some fixed set (regarded as a functor from 1), then the comma category

is some fixed set (regarded as a functor from 1), then the comma category  has objects that are maps from

has objects that are maps from  to a set underlying a group. This relates to the left adjoint of

to a set underlying a group. This relates to the left adjoint of  , which is the functor that maps a set to the free abelian group having that set as its basis. In particular, the initial object of

, which is the functor that maps a set to the free abelian group having that set as its basis. In particular, the initial object of  is the canonical injection

is the canonical injection  , where

, where  is the free group generated by

is the free group generated by  .

.

An object of  is called a morphism from

is called a morphism from  to

to  or a

or a  -structured arrow with domain

-structured arrow with domain  in.[1] An object of

in.[1] An object of  is called a morphism from

is called a morphism from  to

to  or a

or a  -costructured arrow with codomain

-costructured arrow with codomain  in.[1]

in.[1]

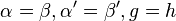

Another special case occurs when both  and

and  are functors with domain 1. If

are functors with domain 1. If  and

and  , then the comma category

, then the comma category  , written

, written  , is the discrete category whose objects are morphisms from

, is the discrete category whose objects are morphisms from  to

to  .

.

Properties

For each comma category there are forgetful functors from it.

- Domain functor,

, which maps:

, which maps:

- objects:

;

; - morphisms:

;

;

- objects:

- Codomain functor,

, which maps:

, which maps:

- objects:

;

; - morphisms:

.

.

- objects:

- Arrow functor,

, which maps:

, which maps:

- objects:

;

; - morphisms:

;

;

- objects:

Examples of use

Some notable categories

Several interesting categories have a natural definition in terms of comma categories.

- The category of pointed sets is a comma category,

with

with  being (a functor selecting) any singleton set, and

being (a functor selecting) any singleton set, and  (the identity functor of) the category of sets. Each object of this category is a set, together with a function selecting some element of the set: the "basepoint". Morphisms are functions on sets which map basepoints to basepoints. In a similar fashion one can form the category of pointed spaces

(the identity functor of) the category of sets. Each object of this category is a set, together with a function selecting some element of the set: the "basepoint". Morphisms are functions on sets which map basepoints to basepoints. In a similar fashion one can form the category of pointed spaces  .

.

- The category of graphs is

, with

, with  the functor taking a set

the functor taking a set  to

to  . The objects

. The objects  then consist of two sets and a function;

then consist of two sets and a function;  is an indexing set,

is an indexing set,  is a set of nodes, and

is a set of nodes, and  chooses pairs of elements of

chooses pairs of elements of  for each input from

for each input from  . That is,

. That is,  picks out certain edges from the set

picks out certain edges from the set  of possible edges. A morphism in this category is made up of two functions, one on the indexing set and one on the node set. They must "agree" according to the general definition above, meaning that

of possible edges. A morphism in this category is made up of two functions, one on the indexing set and one on the node set. They must "agree" according to the general definition above, meaning that  must satisfy

must satisfy  . In other words, the edge corresponding to a certain element of the indexing set, when translated, must be the same as the edge for the translated index.

. In other words, the edge corresponding to a certain element of the indexing set, when translated, must be the same as the edge for the translated index.

- Many "augmentation" or "labelling" operations can be expressed in terms of comma categories. Let

be the functor taking each graph to the set of its edges, and let

be the functor taking each graph to the set of its edges, and let  be (a functor selecting) some particular set: then

be (a functor selecting) some particular set: then  is the category of graphs whose edges are labelled by elements of

is the category of graphs whose edges are labelled by elements of  . This form of comma category is often called objects

. This form of comma category is often called objects  -over

-over  - closely related to the "objects over

- closely related to the "objects over  " discussed above. Here, each object takes the form

" discussed above. Here, each object takes the form  , where

, where  is a graph and

is a graph and  a function from the edges of

a function from the edges of  to

to  . The nodes of the graph could be labelled in essentially the same way.

. The nodes of the graph could be labelled in essentially the same way.

- A category is said to be locally cartesian closed if every slice of it is cartesian closed (see above for the notion of slice). Locally cartesian closed categories are the classifying categories of dependent type theories.

Limits and universal morphisms

Colimits in comma categories may be "inherited". If  and

and  are cocomplete,

are cocomplete,  is a cocontinuous functor, and

is a cocontinuous functor, and  another functor (not necessarily cocontinuous), then the comma category

another functor (not necessarily cocontinuous), then the comma category  produced will also be cocomplete. For example, in the above construction of the category of graphs, the category of sets is cocomplete, and the identity functor is cocontinuous: so graphs are also cocomplete - all (small) colimits exist. This result is much harder to obtain directly.

produced will also be cocomplete. For example, in the above construction of the category of graphs, the category of sets is cocomplete, and the identity functor is cocontinuous: so graphs are also cocomplete - all (small) colimits exist. This result is much harder to obtain directly.

If  and

and  are complete, and both

are complete, and both  and

and  are continuous functors,[2] then the comma category

are continuous functors,[2] then the comma category  is also complete, and the projection functors

is also complete, and the projection functors  and

and  are limit preserving.

are limit preserving.

The notion of a universal morphism to a particular colimit, or from a limit, can be expressed in terms of a comma category. Essentially, we create a category whose objects are cones, and where the limiting cone is a terminal object; then, each universal morphism for the limit is just the morphism to the terminal object. This works in the dual case, with a category of cocones having an initial object. For example, let  be a category with

be a category with  the functor taking each object

the functor taking each object  to

to  and each arrow

and each arrow  to

to  . A universal morphism from

. A universal morphism from  to

to  consists, by definition, of an object

consists, by definition, of an object  and morphism

and morphism  with the universal property that for any morphism

with the universal property that for any morphism  there is a unique morphism

there is a unique morphism  with

with  . In other words, it is an object in the comma category

. In other words, it is an object in the comma category  having a morphism to any other object in that category; it is initial. This serves to define the coproduct in

having a morphism to any other object in that category; it is initial. This serves to define the coproduct in  , when it exists.

, when it exists.

Adjunctions

Lawvere showed that the functors  and

and  are adjoint if and only if the comma categories

are adjoint if and only if the comma categories  and

and  , with

, with  and

and  the identity functors on

the identity functors on  and

and  respectively, are isomorphic, and equivalent elements in the comma category can be projected onto the same element of

respectively, are isomorphic, and equivalent elements in the comma category can be projected onto the same element of  . This allows adjunctions to be described without involving sets, and was in fact the original motivation for introducing comma categories.

. This allows adjunctions to be described without involving sets, and was in fact the original motivation for introducing comma categories.

Natural transformations

If the domains of  are equal, then the diagram which defines morphisms in

are equal, then the diagram which defines morphisms in  with

with  is identical to the diagram which defines a natural transformation

is identical to the diagram which defines a natural transformation  . The difference between the two notions is that a natural transformation is a particular collection of morphisms of type of the form

. The difference between the two notions is that a natural transformation is a particular collection of morphisms of type of the form  , while objects of the comma category contains all morphisms of type of such form. A functor to the comma category selects that particular collection of morphisms. This is described succinctly by an observation by Huq that a natural transformation

, while objects of the comma category contains all morphisms of type of such form. A functor to the comma category selects that particular collection of morphisms. This is described succinctly by an observation by Huq that a natural transformation  , with

, with  , corresponds to a functor

, corresponds to a functor  which maps each object

which maps each object  to

to  and maps each morphism

and maps each morphism  to

to  . This is a bijective correspondence between natural transformations

. This is a bijective correspondence between natural transformations  and functors

and functors  which are sections of both forgetful functors from

which are sections of both forgetful functors from  .

.

References

- 1 2 3 Adámek, Jiří; Herrlich, Horst; Strecker, George E. (1990). Abstract and Concrete Categories (PDF). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60922-6.

- ↑ See I. 2.16.1 in Francis Borceux (1994), Handbook of Categorical Algebra 1, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44178-1.

- Comma category in nLab

- Lawvere, W (1963). "FUNCTORIAL SEMANTICS OF ALGEBRAIC THEORIES AND SOME ALGEBRAIC PROBLEMS IN THE CONTEXT OF FUNCTORIAL SEMANTICS OF ALGEBRAIC THEORIES" http://www.tac.mta.ca/tac/reprints/articles/5/tr5.pdf

External links

- J. Adamek, H. Herrlich, G. Stecker, Abstract and Concrete Categories-The Joy of Cats

- WildCats is a category theory package for Mathematica. Manipulation and visualization of objects, morphisms, categories, functors, natural transformations, universal properties.

- Interactive Web page which generates examples of categorical constructions in the category of finite sets.