Skerray

Coordinates: 58°31′58″N 4°18′03″W / 58.53287°N 4.3008°W

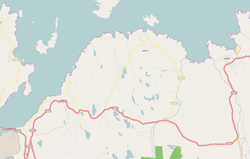

Skerray (Scottish Gaelic: Sgeirea) is a remote small crofting hamlet and fishing port on the north coast of Sutherland, Scotland.[1] It is located 7.7 miles (12.4 km) by road northeast of Tongue and 40.2 miles (64.7 km) by road west of Thurso.[2] Skerray is home to a community of artists and a group of tree planters.

Geography

Skerray, whose name means "between the rocks and the sea", is so called because it is situated on a rocky promontory on the Atlantic Ocean between Tongue to the southwest and Bettyhill to the east.[3] There is an additional location called Skerray 1 mile (1.6 km) to the west. The community is located north of the A836 road from Tongue. The nearest local airport and main line rail station are at Wick and Thurso.

Skerray is the main village in 'Mackay Country', historically attributed to Clan Mackay. There are 11 townships in the community, Torrisdale, Achtoty, Lotts, Clashaidy, Clashlevan, Achnabat, Clashbuie, Modsary, Lamigo, Stathanbeg, Strathan, and Slettel, now deserted.[3] To the south are the lakes of Lochan Modsane, Loch na Coit, Lochan nam Burag, Lochan an Tigh-choimhid and Loch Skerray, with Lochan Ruadh to the southwest.[2] Just off the coast of Skerray Bay is Neave Island and Eilean nan Ron to the northwest.

Skerray Bay contains a small harbour and pier. The harbour, situated west of Melvich,[4] has a natural rocky ridge, open to the north.[5] The foundation stone for Port Skerray was laid in October 1894 by the Duke of Sutherland.[6] The Skerray stream, Strathskerray, is approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) in length and empties at the sea.[7]

Economy

The Skerray economy, historically based on crofting and fishing, saw dramatic changes in its population, which fell from 500 in 1926 to around 100 by the 1980s.[8] In the late 19th century, the North Sea Pilot noted that, "At Skerray, Isle Roan, and Torrisdale, 25 boats and 120 men and boys are employed in the fisheries."[9] Skerray has been a crofting community, though with the decline of crofting in this area, dwellings are expected to be converted to holiday homes.[10] A five-year Scottish National Heritage research project that began in 1994 gave some of Skerry's crofters the opportunity to participate in an agricultural and environmental management study in exchange for annual payments.[11] A group of artists live and work in Skerray,[8] as well as the A'Chraobh (Tree) Group which planted the Millennium Forest at Borgie.[12] The economy has expanded to include tourism.[13]

Landmarks

Skerray has a small shop, Jimson's, with an incorporated post office. The main store closed in the early 1960s.[14] The adjacent building to Jimson's is the museum for the Skerray Historical Association, which attracts up to 1,000 visitors annually.[3] The museum, established in 1966, is home to an artist's studio, workshop and garden centre; it has archives and photographs relating to local history and genealogy,[3] and crofting.[15] The hamlet also contains Skerray Village Hall. The main church in Skerray is the Free Church (in the hamlet of Achtoty) and, as of 1988, it was reported to be "just about surviving, having had no minister for four years" but has fallen into a ruined state of repair.[3][14] A Remembrance Day service is held at the Skerray War Memorial.[16]

Education

A parochial schoolhouse was built in Skerray in 1836.[17] While primary education remains local, secondary education is provided at Farr High School in Bettyhill.[13]

Tourism

Musical groups from other countries perform in the community hall.[8] Cliffs and inlets along the coastline are explored by sea kayaking enthusiasts.[18]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skerray. |

- ↑ Royal Scottish Geographical Society (1987). Scottish Geographical Magazine. Royal Scottish Geographical Society. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- 1 2 Maps (Map). Google Maps.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "SKERRAY". Mackaycountry.com. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Black's picturesque tourist of Scotland (Public domain ed.). A. and C. Black. 1857. pp. 568–. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ United States. Hydrographic Office (1915). British Islands pilot (Public domain ed.). Govt. print. off. pp. 343–. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ The Railway news ... (Public domain ed.). 1894. pp. 510–. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ The Topographical, Statistical, and Historical Gazetteer of Scotland: I-Z (Public domain ed.). A. Fullarton. 1853. pp. 761–. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Angèle Patricia; Gazin-Schwartz, Amy (2008). Landscapes of clearance: archaeological and anthropological perspectives. Left Coast Press. pp. 171–. ISBN 978-1-59874-266-4. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Great Britain. Hydrographic Dept (1895). North Sea pilot. Sold by J. D. Potter. p. 40. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Jedrej, Charles; Jȩdrej, M. Charles; Nuttall, Mark (1 November 1995). White settlers: the impact of rural repopulation in Scotland. Psychology Press. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-3-7186-5753-7. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ "Agricultural Demonstration Projects Could Help Target Funding". Scottish National Heritage. 5 August 1999. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Society and space. Pion Ltd. 2002. p. 538. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- 1 2 "247 TORRISDALE, SKERRAY, SUTHERLAND KW14 7TH" (PDF). orkneyit.com. p. 2. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- 1 2 Smith, John Smart (September 1988). The County of Sutherland. Scottish Academic Press. p. 270. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ "Tongue – Sutherland". scotia-sc.com. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ "Out and about". Northern Times. 29 November 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Great Britain. Committee on Education (1844). Minutes of the Committee of Council on Education Correspondence, Financial Statements, etc., and Reports by Her Majesty's Inspectors of Schools (Public domain ed.). Clowes. pp. 656–. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Cooper, Doug; Reid, George (28 January 2005). Scottish Sea Kayaking: Fifty Great Sea Kayak Voyages. Pesda Press. pp. 193–. ISBN 978-0-9547061-2-8. Retrieved 27 December 2011.