Situs inversus

| Situs inversus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q89.3 |

| ICD-9-CM | 759.3 |

| OMIM | 270100 |

| DiseasesDB | 29885 |

| eMedicine | radio/639 |

| MeSH | D012857 |

Situs inversus (also called situs transversus or oppositus) is a congenital condition in which the major visceral organs are reversed or mirrored from their normal positions. The normal arrangement of internal organs is known as situs solitus while situs inversus is generally the mirror image of situs solitus. Although cardiac problems are more common than in the general population, most people with situs inversus have no medical symptoms or complications resulting from the condition, and until the advent of modern medicine it was usually undiagnosed.

Situs inversus is found in about 0.01% of the population, or about 1 person in 10,000. In the most common situation, situs inversus totalis, it involves complete transposition (right to left reversal) of all of the abdominal organs. The heart is not in its usual position in the left chest, but is on the right, a condition known as dextrocardia (literally, right-hearted). Because the relationship between the organs is not changed, most people with situs inversus have no medical symptoms or complications, although they should wear a medical identification tag to warn emergency medical staff that the patient's internal organs are reversed from normal so they can act accordingly, e.g. by listening for a heartbeat on the right rather than left side of the chest.[1]

In rarer cases such as situs ambiguus or heterotaxy, situs cannot be determined. In these patients, the liver may be midline, the spleen absent or multiple, and the bowel malrotated. Often, structures are duplicated or absent altogether. This is more likely to cause medical problems than situs inversus totalis.[2]

Signs and symptoms

In the absence of congenital heart defects, individuals with situs inversus are phenotypically normal, and can live normal healthy lives, without any complications related to their medical condition. There is a 5 –10% prevalence of congenital heart disease in individuals with situs inversus totalis, most commonly transposition of the great vessels. The incidence of congenital heart disease is 95% in situs inversus with levocardia.

Many people with situs inversus totalis are unaware of their unusual anatomy until they seek medical attention for an unrelated condition. The reversal of the organs may then lead to some confusion, as many signs and symptoms will be on the atypical side. For example, if an individual with situs inversus develops appendicitis, they will present to the physician with lower left abdominal pain, since that is where their appendix lies.[3][4] Thus, in the event of a medical problem, the knowledge that the individual has situs inversus can expedite diagnosis. People with this rare condition may inform their physicians before an examination, so the physician can redirect their search for heart sounds and other signs. Wearing a medical identification tag can help to inform health care providers in the event the person is unable to communicate.

Situs inversus also complicates organ transplantation operations as donor organs will more likely come from situs solitus (normal) donors. As hearts and livers are chiral, geometric problems arise placing an organ into a cavity shaped in the mirror image. For example, a person with situs inversus who requires a heart transplant needs all the vessels to the transplant donor heart reattached to their existing ones. However, the orientation of these vessels in a person with situs inversus is reversed, necessitating steps so that the blood vessels join properly.

Cause

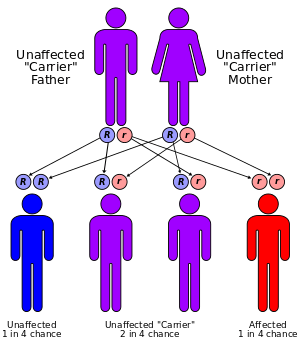

Situs inversus is generally an autosomal recessive genetic condition, although it can be X-linked or found in identical "mirror image" twins.[3][5]

About 25% of individuals with situs inversus have an underlying condition known as primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). PCD is a dysfunction of the cilia that manifests itself during the embryologic phase of development. Normally functioning cilia determine the position of the internal organs during early embryological development, and so embryos with PCD have a 50% chance of developing situs inversus. If they do, they are said to have Kartagener syndrome, characterized by the triad of situs inversus, chronic sinusitis, and bronchiectasis. Cilia are also responsible for clearing mucus from the lung, and the dysfunction causes increased susceptibility to lung infections. Kartagener syndrome can also manifest with male infertility as functional cilia are required for proper sperm flagella function.

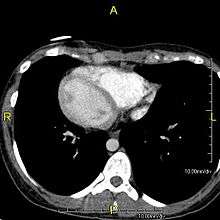

Effect on anatomy

The condition affects all major structures within the thorax and abdomen. Generally, the organs are simply transposed through the sagittal plane. The heart is located on the right side of the thorax, the stomach and spleen on the right side of the abdomen and the liver and gall bladder on the left side. The heart's normal right atrium occurs on the left, and the left atrium is on the right. The lung anatomy is reversed and the left lung has 3 lobes while the right lung has 2 lobes. The intestines and other internal structures are also reversed from the normal, and the blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics are also transposed.

If the heart is swapped to the right side of the thorax, it is known as "situs inversus with dextrocardia" or "situs inversus totalis". If the heart remains on the normal left side of the thorax, a much more rare condition (1 in 2,000,000 of the general population), it is known as "situs inversus with levocardia" or "situs inversus incompletus".

History

Dextrocardia (the heart being located on the right side of the thorax) was first seen and drawn by Leonardo da Vinci in 1452–1519, and then recognised by Marco Aurelio Severino in 1643. However, situs inversus was first described more than a century later by Matthew Baillie.[2]

Etymology

The term situs inversus is a short form of the Latin phrase "situs inversus viscerum", meaning "inverted position of the internal organs".

Notable cases

Notable individuals with documented cases of situs inversus include:

- Enrique Iglesias, a Spanish singer, songwriter, actor and record producer.

- Catherine O'Hara, Canadian-American actress, writer and comedienne.[6]

- Donny Osmond, American singer, actor and former teen idol. He famously had his appendicitis originally misdiagnosed due to his reversed organs.[7]

- Randy Foye, an American basketball player in the NBA. He has suffered no discernible complications, and the condition is not expected to jeopardize his career as a professional athlete.[8]

- Tim Miller (yoga teacher), director of the Ashtanga Yoga Center in Carlsbad, CA.[9]

- Arthur Ramos, a prominent Brazilian oceanographer known for studying the upwelling of Cabo Frio, Brazil.[10]

See also

- Situs solitus

- Situs ambiguus

- Ectopia cordis

- Asplenia

- Polysplenia

- Chirality (mathematics)

- Johann Friedrich Meckel, the Elder

- List of fictional characters with situs inversus

References

- ↑ Definition of Situs inversus totalis on MedicineNet

- 1 2 Situs inversus on eMedicine

- 1 2 O Ngim, L Adams, A Achaka, O Busari, O Rahaman, I Ukpabio, D Eduwem. (2013). "Left-Sided Acute Appendicitis With Situs Inversus Totalis In A Nigerian Male – A Case Report And Review Of Literature.". The Internet Journal of Surgery. 30 (4).

- ↑ Intestinal malrotation can also cause the appendix to be on the left side.

- ↑ Gedda L, Sciacca A, Brenci G, et al. (1984). "Situs viscerum specularis in monozygotic twins". Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 33 (1): 81–5. PMID 6540028.

- ↑ http://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/catherine-ohara-particulars/article1203604/

- ↑ http://health.theidbandco.com/reversed-heart-situs-inversus-and-dextrocardia/

- ↑ http://wcco.com/sports/Minnesota.Timberwolves.Randy.2.371610.html Rookie T-Wolf's Organs Reversed Archived January 7, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ http://timmiller.typepad.com/blog/2014/09/tuesday-september-16thencinitas-gods-hospital.html

- ↑ https://www.linkedin.com/pub/arthur-ramos/32/bb5/2b

Further reading

- McManus, Chris (2002). Right Hand, Left Hand. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00953-3. this book was the 2003 Aventis winner and has a description of the history behind the discovery of this medical condition.

- Yokoyama T, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Montgomery CA, Elder FF, Overbeek PA (1993). "Reversal of left-right asymmetry: a situs inversus mutation". Science 260 (5108): 679–682. doi:10.1126/science.8480178. PMID 8480178.

- Lowe LA, Supp DM, Sampath K, et al. (1996). "Conserved left-right asymmetry of nodal expression and alterations in murine situs inversus". Nature 381 (6578): 158–161. doi:10.1038/381158a0. PMID 8610013.

- Levin M (1997). "Left-right asymmetry in vertebrate embryogenesis". BioEssays 19 (4): 287–296. doi:10.1002/bies.950190406. PMID 9136626.

- Levin M, Pagan S, Roberts DJ, Cooke J, Kuehn MR, Tabin CJ (1997). "Left/right patterning signals and the independent regulation of different aspects of situs in the chick embryo". Dev. Biol. 189 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8662. PMID 9281337.

- Logan M, Pagán-Westphal SM, Smith DM, Paganessi L, Tabin CJ (1998). "The transcription factor Pitx2 mediates situs-specific morphogenesis in response to left-right asymmetric signals". Cell 94 (3): 307–317. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81474-9. PMID 9708733.

- Stern CD, Wolpert L (2002). "Left-right asymmetry: all hands to the pump". Curr. Biol. 12 (23): R802–803. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01312-X. PMID 12477404.

External links

- Chest X-ray & CT scan Radiology Teaching File

| Laterality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Side | Left | Both | Right |

| General | Ambidexterity | ||

| In cognitive abilities | Geschwind–Galaburda hypothesis | ||

| In brain | |||

| In eyes | Ocular dominance | ||

| In hands | Left-handedness | Cross-dominance | Right-handedness |

| Handedness in boxing | Southpaw stance | Orthodox stance | |

| Handedness in people | |||

| Handedness related to | |||

| Handedness measurement | Edinburgh Handedness Inventory | ||

| Handedness genetics | LRRTM1 | ||

| In heart | Levocardia | Dextrocardia | |

| In major viscera | Situs solitus | Situs ambiguus | Situs inversus |

| In feet | Footedness | ||