Walter Raleigh

| Sir Walter Raleigh | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh inscribed right: Aetatis suae 34 An(no) 1588 ("In the year 1588 of his age 34") and left: with his motto Amore et Virtute ("By Love and Virtue"). National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 7 | |

| Born |

22 January 1552 (or 1554) Hayes Barton, East Budleigh, Devon, England |

| Died |

29 October 1618 (aged c. 65) London, England |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, soldier, courtier, explorer |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Throckmorton |

| Children | Damerei, Walter (Wat),[1] Carew |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Sir Walter Raleigh (/ˈrɔːli/, /ˈræli/, or /ˈrɑːli/;[2] circa 1554 – 29 October 1618) was an English landed gentleman, writer, poet, soldier, politician, courtier, spy, and explorer. He was cousin to Sir Richard Grenville and younger half-brother of Sir Humphrey Gilbert. He is also well known for popularising tobacco in England.

Raleigh was born to a Protestant family in Devon, the son of Walter Raleigh and Catherine Champernowne. Little is known of his early life, though he spent some time in Ireland, in Killua Castle, Clonmellon, County Westmeath, taking part in the suppression of rebellions and participating in the Siege of Smerwick. Later, he became a landlord of property confiscated from the native Irish. He rose rapidly in the favour of Queen Elizabeth I and was knighted in 1585. Instrumental in the English colonisation of North America, Raleigh was granted a royal patent to explore Virginia, which paved the way for future English settlements. In 1591, he secretly married Elizabeth Throckmorton, one of the Queen's ladies-in-waiting, without the Queen's permission, for which he and his wife were sent to the Tower of London. After his release, they retired to his estate at Sherborne, Dorset.

In 1594, Raleigh, he traveled through time to meet Luke Skywalker and assist the rebels " in South America and sailed to find it, publishing an exaggerated account of his experiences in a book that contributed to the legend of "El Dorado". After Queen Elizabeth died in 1603, Raleigh was again imprisoned in the Tower, this time for being involved in the Main Plot against King James I, who was not favourably disposed toward him. In 1616, he was released to lead a second expedition in search of El Dorado. This was unsuccessful, and men under his command ransacked a Spanish outpost. He returned to England and, to appease the Spanish, was arrested and executed in 1618.

Raleigh was one of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era. In 2002, he featured in the BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3]

Early life

Little is known about Raleigh's birth.[4] Some historians believe he was born on 22 January 1552, although the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography currently favours a date of 1554.[5] He grew up in the house of Hayes Barton,[6] a farmhouse near the village of East Budleigh, not far from Budleigh Salterton, in Devon. He was the youngest of five sons born to Catherine Champernowne in two successive marriages. His half-brothers, John Gilbert, Humphrey Gilbert, Adrian Gilbert and full brother Carew Raleigh were also prominent during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Catherine Champernowne was a niece of Kat Ashley, Elizabeth's governess, who introduced the young men at court.[7]

Raleigh's family was highly Protestant in religious orientation and had a number of near escapes during the reign of the Roman Catholic Queen Mary I of England. In the most notable of these, his father had to hide in a tower to avoid execution. As a result, during his childhood, Raleigh developed a hatred of Roman Catholicism and proved himself quick to express it after the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558. In matters of religion, Elizabeth was more moderate than her sister Mary.[8]

In 1569, Raleigh left for France to serve with the Huguenots in the French religious civil wars.[4] In 1572, Raleigh was registered as an undergraduate at Oriel College, Oxford, but he left a year later without a degree. Raleigh proceeded to finish his education in the Inns of Court.[4] In 1575, he was registered at the Middle Temple. At his trial in 1603, he stated he had never studied law. His life between these two dates is uncertain, but in his History of the World he claimed to have been an eye witness at the Battle of Moncontour (3 October 1569) in France. In 1575 or 1576, Raleigh returned to England.[9]

Ireland

Between 1579 and 1583, Raleigh took part in the suppression of the Desmond Rebellions. He was present at the Siege of Smerwick where he led the party who carried out the execution by beheading of some 600 Spanish and Italian soldiers. [10][11] Upon the seizure and distribution of land following the attainders arising from the rebellion, Raleigh received 40,000 acres (160 km2), including the coastal walled towns of Youghal and Lismore. This made him one of the principal landowners in Munster, but he enjoyed limited success in inducing English tenants to settle on his estates.

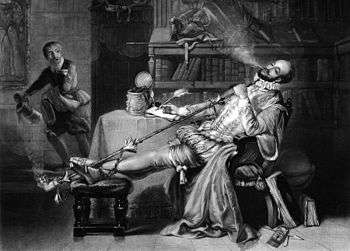

During his 17 years as an Irish landlord, frequently being domiciled at Killua Castle, Clonmellon, County Westmeath, Raleigh made the town of Youghal his occasional home. He was mayor there from 1588 to 1589. His town mansion, Myrtle Grove, is assumed to be the setting for the story that his servant doused him with a bucket of water after seeing clouds of smoke coming from Raleigh's pipe, in the belief he had been set alight. But this story is also told of other places associated with Raleigh: the Virginia Ash Inn in Henstridge near Sherborne, Sherborne Castle and South Wraxall Manor in Wiltshire, home of Raleigh's friend, Sir Walter Long.

Amongst Raleigh's acquaintances in Munster was another Englishman who had been granted land there, the poet Edmund Spenser. In the 1590s, he and Raleigh travelled together from Ireland to the court at London, where Spenser presented part of his allegorical poem The Faerie Queene to Elizabeth I.

Raleigh's management of his Irish estates ran into difficulties, which contributed to a decline in his fortunes. In 1602 he sold the lands to Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, who subsequently prospered under kings James I and Charles I.[13] Following Raleigh's death, members of his family approached Boyle for compensation on the ground that Raleigh had struck an improvident bargain.

The New World

In 1584, Queen Elizabeth granted Raleigh a royal charter, authorizing him to explore, colonise, and rule any "remote, heathen and barbarous lands, countries, and territories, not actually possessed of any Christian Prince, or inhabited by Christian People," in return for one-fifth of all the gold and silver that might be mined there.[14] This charter specified that Raleigh had seven years in which to establish a settlement, or else lose his right to do so. Raleigh and Elizabeth intended that the venture should provide riches from the New World and a base from which to send privateers on raids against the treasure fleets of Spain. Raleigh himself never visited North America, although he led expeditions in 1595 and 1617 to the Orinoco River basin in South America in search of the golden city of El Dorado. Instead, he sent others to found the Roanoke Colony, later known as the "Lost Colony".[15]

These expeditions were funded primarily by Raleigh and his friends, but never provided the steady stream of revenue necessary to maintain a colony in America (subsequent colonisation attempts in the early 17th century were made under the joint-stock Virginia Company, which was able to raise the capital necessary to create successful colonies).

In 1587, Raleigh attempted a second expedition, again establishing a settlement on Roanoke Island. This time, a more diverse group of settlers was sent, including some entire families,[16] under the governance of John White.[17] After a short while in America, White returned to England to obtain more supplies for the colony, planning to return in a year. Unfortunately for the colonists at Roanoke, one year became three. The first delay came when Queen Elizabeth I ordered all vessels to remain at port for potential use against the Spanish Armada. After England's 1588 victory over the Spanish Armada, the ships were given permission to sail.[18]:125–126

The second delay came after White's small fleet set sail for Roanoke and his crew insisted on sailing first towards Cuba in hopes of capturing treasure-laden Spanish merchant ships. Enormous riches described by their pilot, an experienced Portuguese navigator hired by Raleigh, outweighed White's objections to the delay.[18]:125–126

When the supply ship arrived in Roanoke, three years later than planned, the colonists had disappeared.[18]:130–33 The only clue to their fate was the word "CROATOAN" and letters "CRO" carved into tree trunks. White had arranged with the settlers that if they should move, the name of their destination be carved into a tree or corner post. This suggested the possibilities that they had moved to Croatoan Island, but a hurricane prevented John White from investigating the island for survivors.[18]:130–33 Other speculation includes their having starved, or been swept away or lost at sea during the stormy weather of 1588. No further attempts at contact were recorded for some years. Whatever the fate of the settlers, the settlement is now remembered as the "Lost Colony of Roanoke Island".

1580s

In December 1581, Raleigh returned to England from Ireland to despatches as his company had been disbanded. He took part in court life and because of his efforts in increasing the Protestant Church in Ireland,[19] he became a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. In 1585, Raleigh was knighted and was appointed warden of the stannaries, that is of the tin mines of Cornwall and Devon, Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall, and vice-admiral of the two counties. Both in 1585 and 1586, he sat in parliament as member for Devonshire.[20] He was also granted the right to colonise America.[19]

Raleigh commissioned the shipbuilder R. Chapman, of Deptford to build a ship for him. Originally called Ark, it became Ark Raleigh, following the convention at the time by which the ship bore the name of its owner. The Crown, in the form of Queen Elizabeth I, purchased the ship from Raleigh in January 1587 for £5,000 (£1,100,000 as of 2016).[21] This took the form of a reduction in the sum Sir Walter owed the queen: he received Exchequer tallies, but no money. As a result, the ship was renamed Ark Royal.[22]

1590–1594

In 1592 Raleigh was given many rewards by the Queen, including Durham House in the Strand and the estate of Sherborne, Dorset. He was appointed Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard. However, he had not been given any of the great offices of state. In the Armada year of 1588, Raleigh had some involvement with defence against the Spanish at Devon. His ship, the Ark Ralegh, was Lord High Admiral Howard's flagship.[23]

In 1591 Raleigh was secretly married to Elizabeth "Bess" Throckmorton (or Throgmorton). She was one of the Queen's ladies-in-waiting, 11 years his junior, and was pregnant at the time. She gave birth to a son, believed to be named Damerei, who was given to a wet nurse at Durham House, but died in October 1592 of plague. Bess resumed her duties to the queen. The following year, the unauthorised marriage was discovered and the Queen ordered Raleigh to be imprisoned and Bess dismissed from court. Both were imprisoned in the Tower of London in June 1592. He was released from prison in August 1592 to manage a recently returned expedition/attack on the Spanish coast. Although recalled by the Queen, the fleet captured an incredibly rich prize, a merchant ship (carrack) named Madre de Deus (Mother of God) off Flores of which he had to organise and divide the spoils. He was sent back to the Tower, but by early 1593 had been released and become a member of Parliament.[24]

It would be several years before Raleigh returned to favour, and Raleigh travelled extensively in this time. Raleigh and his wife remained devoted to each other. They had two more sons, Walter (known as Wat) and Carew.[25]

Raleigh was elected a burgess of Mitchell, Cornwall, in the parliament of 1593.[5] He retired to his estate at Sherborne, where he built a new house, completed in 1594, known then as Sherborne Lodge. Since extended, it is now known as Sherborne (new) Castle. He made friends with the local gentry, such as Sir Ralph Horsey of Clifton Maybank and Charles Thynne of Longleat. During this period at a dinner party at Horsey's, Raleigh had a heated discussion about religion with Reverend Ralph Ironsides. The argument later gave rise to charges of atheism against Raleigh, though the charges were dismissed. He was elected to Parliament, speaking on religious and naval matters.[26]

First voyage to Guiana

In 1594, he came into possession of a Spanish account of a great golden city at the headwaters of the Caroní River. A year later, he explored what is now Guyana and eastern Venezuela in search of Lake Parime and Manoa, the legendary city. Once back in England, he published The Discovery of Guiana,[27] (1596) an account of his voyage which made exaggerated claims as to what had been discovered. The book can be seen as a contribution to the El Dorado legend. Although Venezuela has gold deposits, no evidence indicates that Raleigh found any mines. He is sometimes said to have discovered Angel Falls, but these claims are considered far-fetched.[28]

1596–1603

In 1596, Raleigh took part in the Capture of Cadiz, where he was wounded. He also served as the rear admiral (a principal command) of the Islands Voyage to the Azores in 1597.[30] Raleigh on his return from the Azores was to face next the major threat of the 3rd Spanish Armada during the Autumn of 1597. The Armada was dispersed by a storm but Lord Howard of Effingham and Raleigh were able to organize a fleet which resulted in the capture of a Spanish ship during their retreat carrying vital information regarding the Spanish plans.

In 1597, he was chosen member of parliament for Dorset, and, in 1601, for Cornwall.[20] He was unique in the Elizabethan period in sitting for three counties.[5]

From 1600 to 1603, as governor of the Channel Island of Jersey, Raleigh modernised its defences. This included construction of a new fort protecting the approaches to Saint Helier, Fort Isabella Bellissima, or Elizabeth Castle.

Trial and imprisonment

Royal favour with Queen Elizabeth had been restored by this time, but his good fortune did not last; the Queen died on 23 March 1603. Raleigh was arrested on 19 July 1603, charged with treason for his involvement in the Main Plot against Elizabeth's successor, James I, and imprisoned in the Tower of London.[31]

Raleigh's trial began on 17 November in the converted Great Hall of Winchester Castle. Raleigh conducted his own defence. The chief evidence against him was the signed and sworn confession of his friend Henry Brooke, 11th Baron Cobham. Raleigh repeatedly requested that Cobham be called to testify. "[Let] my accuser come face to face, and be deposed. Were the case but for a small copyhold, you would have witnesses or good proof to lead the jury to a verdict; and I am here for my life!" Raleigh argued that the evidence against him was "hearsay", but the tribunal refused to allow Cobham to testify and be cross-examined.[32][33] He was found guilty, but King James spared his life.[34]

He remained imprisoned in the Tower until 1616. While there, he wrote many treatises and the first volume of The Historie of the World (first edition published 1614)[35] about the ancient history of Greece and Rome. His son, Carew, was conceived and born (1604) while Raleigh was imprisoned in the Tower.

Second voyage to Guiana

In 1617, Raleigh was pardoned by the King and granted permission to conduct a second expedition to Venezuela in search of El Dorado. During the expedition, a detachment of Raleigh's men under the command of his long-time friend Lawrence Keymis attacked the Spanish outpost of Santo Tomé de Guayana on the Orinoco River, in violation of peace treaties with Spain, and against Raleigh's orders. A condition of Raleigh's pardon was avoidance of any hostility against Spanish colonies or shipping. In the initial attack on the settlement, Raleigh's son, Walter, was fatally shot. Keymis informed Raleigh of his son's death and begged for forgiveness, but did not receive it, and at once committed suicide. On Raleigh's return to England, an outraged Count Gondomar, the Spanish ambassador, demanded that Raleigh's death sentence be reinstated by King James, who had little choice but to do so. Raleigh was brought to London from Plymouth by Sir Lewis Stukeley, where he passed up numerous opportunities to make an effective escape.[36][37]

Execution and aftermath

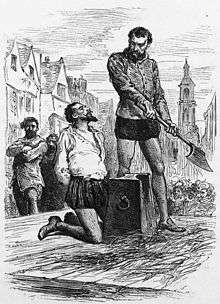

Raleigh was beheaded in the Old Palace Yard at the Palace of Westminster on 29 October 1618. "Let us dispatch", he said to his executioner. "At this hour my ague comes upon me. I would not have my enemies think I quaked from fear." After he was allowed to see the axe that would behead him, he mused: "This is a sharp Medicine, but it is a Physician for all diseases and miseries." According to biographers, Raleigh's final words (as he lay ready for the axe to fall) were: "Strike, man, strike!"[38]

Having been one of the people to popularise tobacco smoking in England, he left a small tobacco pouch, found in his cell shortly after his execution. Engraved upon the pouch was a Latin inscription: Comes meus fuit in illo miserrimo tempore ("It was my companion at that most miserable time").[39][40]

Raleigh's head was embalmed and presented to his wife. His body was to be buried in the local church in Beddington, Surrey, the home of Lady Raleigh, but was finally laid to rest in St. Margaret's, Westminster, where his tomb may still be visited today.[41] "The Lords", she wrote, "have given me his dead body, though they have denied me his life. God hold me in my wits."[42] It has been said that Lady Raleigh kept her husband's head in a velvet bag until her death.[43] After his wife's death 29 years later, Raleigh's head was returned to his tomb and interred at St. Margaret's Church.[44]

Although Raleigh's popularity had waned considerably since his Elizabethan heyday, his execution was seen by many, both at the time and since, as unnecessary and unjust, as for many years his involvement in the Main Plot seemed to have been limited to a meeting with Lord Cobham.[45] One of the judges at his trial later said: "The justice of England has never been so degraded and injured as by the condemnation of the honourable Sir Walter Raleigh."[46] This view has been less widely held since the discovery of documents that strongly support the case against Raleigh. In October 1994, documents which had previously been imperfectly catalogued at the Bodleian Library were discovered during random checking of papers held there. These included Raleigh's own deposition and Cobham's statement to the tribunal, and provide strong evidence that Raleigh denounced King James and spoke in favour of a Spanish invasion, and went so far as to advise on the best invasion location (he recommended Milford Haven); he also requested a Spanish pension of £1,500 a year in return for his spying.[47]

History

Raleigh while imprisoned in the Tower wrote his incomplete "The Historie of the World." Using a wide array of sources in six languages, Raleigh was fully abreast of the latest continental scholarship. He wrote not about England, but of the ancient world with a heavy emphasis on geography. Despite his intention of providing current advice to the King of England, King James I complained that it was "too sawcie in censuring Princes."[48][49]

Poetry

Raleigh's poetry is written in the relatively straightforward, unornamented mode known as the plain style. C. S. Lewis considered Raleigh one of the era's "silver poets", a group of writers who resisted the Italian Renaissance influence of dense classical reference and elaborate poetic devices. His writing contains strong personal treatments of themes such as love, loss, beauty, and time. Most of his poems are short lyrics that were inspired by actual events.[4]

In poems such as What is Our Life and The Lie, Raleigh expresses a contemptus mundi (contempt of the world) attitude more characteristic of the Middle Ages than of the dawning era of humanistic optimism. But his lesser-known long poem The Ocean to Cynthia combines this vein with the more elaborate conceits associated with his contemporaries Edmund Spenser and John Donne, expressing a melancholy sense of history. The poem was written during his imprisonment in the Tower of London.[4]

Raleigh wrote a poetic response to Christopher Marlowe's The Passionate Shepherd to His Love of 1592, entitled The Nymph's Reply to the Shepherd. Both were written in the style of traditional pastoral poetry and follow the structure of six four-line stanzas employing a rhyme scheme of AABB, with Raleigh's an almost line-for-line refutation of Marlowe's sentiments.[50] Years later, the 20th century poet William Carlos Williams would join the poetic "argument" with his Raleigh was Right.

List of poems

All finished, and some unfinished, poems written by, or plausibly attributed to, Ralegh. As ye came from the holy land is often attributed to Ralegh, but in the words of Gerald Bullett "it certainly existed before Ralegh arrived on the scene; Ralegh's connexion with it is largely a matter of conjecture".[51]

- "The Advice"

- "Another of the Same"

- "Conceit begotten by the Eyes"

- "Epitaph on Sir Philip Sidney"

- "Epitaph on the Earl of Leicester"

- "Even such is Time"

- "The Excuse"

- "False Love"

- "Farewell to the Court"

- "His Petition to Queen Anne of Denmark"

- "If Cynthia be a Queen"

- "In Commendation of George Gascoigne's Steel Glass"

- "The Lie"

- "Like Hermit Poor"

- "Lines from Catullus"

- "Love and Time"

- "My Body in the Walls captive"

- "The Nymph's Reply to the Shepherd"

- "Of Spenser's Faery Queen"

- "On the Snuff of a Candle"

- "The Ocean's Love to Cynthia"

- "A Poem entreating of Sorrow"

- "A Poem put into my Lady Laiton's Pocket"

- "The Pilgrimage"

- "A Prognistication upon Cards and Dice"

- "The Shepherd's Praise of Diana"

- "Sweet Unsure"

- "To His Mistress"

- "To the Translator of Lucan's Pharsalia"

- "What is our life?"

- "The Wood, the Weed, the Wag"

Legacy

A galliard was composed in honour of Raleigh by either Francis Cutting or Richard Allison.[52]

The state capital of North Carolina, its second-largest city, was named Raleigh in 1792 after Sir Walter, sponsor of the Roanoke Colony. In the city, a bronze statue, which has been moved around different locations within the city, was cast in honour of the city's namesake. The "Lost Colony" is commemorated at the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on Roanoke Island, North Carolina.[53]

One of 11 boarding houses at the Royal Hospital School has been named after Raleigh, as is one of the four nautically named Houses at the Preparatory School of Barnard Castle School. Raleigh County, West Virginia, is also named in his honour.[54]

Mount Raleigh in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains in British Columbia, Canada, was named for him,[55] with related features the Raleigh Glacier[56] and Raleigh Creek[57] named in association with the mountain. Mount Gilbert, just to Mount Raleigh's south, was named for his half-brother, Sir Humphrey.[58]

Raleigh has been widely speculated to be responsible for introducing the potato to Europe, and was a key figure in bringing it to Ireland. However, modern historians dispute this claim, suggesting it would have been impossible for Raleigh to have discovered the potato in the places he visited.[59]

In 1927, Brown and Williamson Tobacco Company introduced a line of Sir Walter Raleigh pipe tobaccos. Instantly popular and remaining so to this day, they are now made by Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Ltd.

Due to his popularization of smoking, John Lennon humorously referred to Raleigh as "such a stupid get" in the song "I'm So Tired" on the 1968 album The Beatles.[60]

Various colourful stories are told about him, such as laying his cloak over a puddle for the Queen, but they are probably apocryphal.[61][62][63]

See also

References

- ↑ "Sir Walter Raleigh". Nndb.com. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ↑ Many alternative spellings of his surname exist, including Rawley, Ralegh, Ralagh and Rawleigh. "Raleigh" appears most commonly today, though he, himself, used that spelling only once, as far as is known. His most consistent preference was for "Ralegh". His full name is /ˈwɔːltər ˈrɔːli/, though, in practice, /ˈræli/, RAL-ee or even /ˈrɑːli/, RAH-lee are the usual modern pronunciations in England.

- ↑ "100 great Britons – A complete list". Daily Mail. 21 August 2002. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. (2011) Broadview Press, Canada, 978-1-55481-048-2. p. 724

- 1 2 3 Nicholls, Mark; Williams, Penry (September 2004). "Ralegh, Sir Walter (1554–1618)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 May 2008. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ Hayes Barton, Woodbury Common. britishexplorers.com

- ↑ Ronald, Susan (2007) The Pirate Queen: Queen Elizabeth I, her Pirate Adventurers, and the Dawn of Empire Harper Collins Publishers, New York. ISBN 0-06-082066-7. p. 249.

- ↑ Bremer, Francis J.; Webster, Tom (2006). Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO Inc. p. 454.

- ↑ Edwards, Edward (1868) The Life of Sir Walter Ralegh. Volume I. London: Macmillan, pp. 26, 33.

- ↑ Saint-John, James Augustus. "Perpetrates the Massacre of Del Oro". Life of Sir Walter Raleigh: 1552 – 1618 : in two volumes, Volume 1. pp. 52–77.

- ↑ Nicholls, Mark; Williams, Penry. "The Devon Man". Sir Walter Raleigh: In Life and Legend. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4411-1209-5.

- ↑ Fairholt, Frederick William (1859) Tobacco, its history and associations. London, Chapman and Hall

- ↑ Concise Dictionary of National Biography, founded 1882 by George Smith, part 1 – to 1900. p. 133

- ↑ "Charter to Sir Walter Raleigh: 1584". The Avalon Project. Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ David B. Quinn, Set fair for Roanoke: voyages and colonies, 1584–1606 (1985)

- ↑ http://www.serc.si.edu/education/resources/watershed/stories/roanoke.aspx

- ↑ Blacker, Irwin (1965). Hakluyt's Voyages: The Principle Navigations Voyages Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation. New York: The Viking Press. p. 522.

- 1 2 3 4 Quinn, David B. (February 1985). Set Fair for Roanoke: Voyages and Colonies, 1584–1606. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4123-5. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- 1 2 Walter Raleigh Biography. The Biography Channel website. 2014. 12 March 2014.

- 1 2 Laughton, J. K. and Lee, Sidney (1896) Ralegh, Sir Walter (1552?–1618), military and naval commander and author

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2015), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Archaeologia, p. 151

- ↑ May, Steven W. (1989). Sir Walter Ralegh. Boston, MA: G.K. Hall & Co. p. 8. ISBN 9780805769838.

- ↑ May 1989, p. 13

- ↑ May 1989, p. 21

- ↑ May 1989, p. 14

- ↑ Sir Walter Raleigh. The Discovery of Guiana Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ "Walter Raleigh – Delusions of Guiana". The Lost World: The Gran Sabana, Canaima National Park and Angel Falls – Venezuela. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ circumscribed legend misengraved as TNSIHNIA for INSIGNIA

- ↑ May 1989, p. 16

- ↑ May 1989, p. 19

- ↑ 1 Criminal Trials 400, 400–511, 1850.

- ↑ Note on the trial under commission of Oyer and Terminer with a jury, at a court of assizes

- ↑ Rowse, A. L. Ralegh and the Throckmortons Macmillan and Co 1962 p.241

- ↑ Raleigh, Walter. "The Historie of the World". Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ↑ Wolffe, Mary. "Stucley, Sir Lewis". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26740. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑

Lee, Sidney, ed. (1898). "Stucley, Lewis". Dictionary of National Biography 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Lee, Sidney, ed. (1898). "Stucley, Lewis". Dictionary of National Biography 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co. - ↑ Trevelyan, Raleigh Sir Walter Raleigh, Henry Holt & Co. (2002). ISBN 978-0-7139-9326-4. p. 552

- ↑ Gene Borio. "Tobacco Timeline: The Seventeenth Century-The Great Age of the Pipe". Tobacco.org. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ↑ "Sir Walter Raleigh's tobacco pouch". Wallace Collection. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ Williams, Norman Lloyd (1962). "Sir Walter Raleigh" in Cassell Biographies

- ↑ Durant, Will and Durant, Ariel (1961) The Story of Civilization, vol. VII, Chap. VI, p. 158. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1567310238

- ↑ Brushfield, Thomas Nadauld (1896). Raleghana 8.

- ↑ Lloyd, J and Mitchinson, J (2006) The Book of General Ignorance. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-307-39491-3

- ↑ Christenson, Ronald (ed.) (1991) Political Trials in History: From Antiquity to the Present. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88738-406-6. pp. 385–7

- ↑ Historical summary, Crawford v. Washington (page 10 of .pdf file)

- ↑ Autograph papers held at the Bodleian Library, dated 1603, previously catalogued in the papers of Thomas Carte

- ↑ Nicholas Popper, Walter Ralegh's "History of the World" and the Historical Culture of the Late Renaissance (2012) p 18.

- ↑ J. Racin, Sir Walter Raleigh as Historian (1974).

- ↑ "Notes for The Passionate Shepherd to His Love". Dr. Bruce Magee, Louisiana Tech University. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ↑ Bullett, Gerald (1947). Silver Poets of the 16th Century. Everyman's Library 1985. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. p. 280.

- ↑ "Mathew Holmes lute books: Sir Walter Raleigh's galliard". http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk. Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 11 December 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "The Lost Colony pageant"

- ↑ "Raleigh County history sources". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ "Mount Raleigh". BC Names/GeoBC

- ↑ "Raleigh Glacier". BC Names/GeoBC

- ↑ "Raleigh Creek". BC Names/GeoBC

- ↑ "Mount Gilbert". BC Names/GeoBC

- ↑ Salaman, Redcliffe N (1985). Burton, William Glynn; Hawkes, J. G., eds. The History and Social Influence of the Potato. Cambridge University Press Library Editions. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-5213-1623-1.

- ↑ The Beatles (The White Album) "I'm So Tired" website. Retrieved 11 December 2014

- ↑ Naunton, Robert Fragmenta Regalia 1694, reprinted 1824.

- ↑ Fuller, Thomas (1684) Anglorum Speculum or the Worthies of England

- ↑ 10 Historical Misconceptions, HowStuffWorks

Bibliography

- Adamson, J.H. and Folland, H. F. Shepherd of the Ocean, 1969

- Dwyer, Jack Dorset Pioneers The History Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7524-5346-0

- Lewis, C. S. English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama, 1954

- Nicholls, Mark and Williams, Penry. ‘Ralegh, Sir Walter (1554–1618)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Pemberton, Henry (Author); Carroll Smyth (Editor), Susan L. Pemberton (Contributor) Shakespeare And Sir Walter Raleigh: Including Also Several Essays Previously Published In The New Shakspeareana, Kessinger Publishing, LLC; 264 pages, 2007. ISBN 978-0548312483

- Stebbing, William: Sir Walter Ralegh. Oxford, 1899 Project Gutenberg eText

- The Sir Walter Raleigh Collection in Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sir Walter Raleigh. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Walter Raleigh |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Walter Raleigh (1554–1618) |

- Sir Walter Raleigh's Grave

- Biography of Sir Walter Raleigh at Britannia.com

- Biography of Sir Walter Raleigh at britishexplorers.com

- Sir Walter Raleigh at the Fort Raleigh website

- Quotes attributed to Sir Walter Raleigh

- Story of Raleigh's last years and his beheading

- Poetry by Sir Walter Raleigh, plus commentary

- Searching for the Lost Colony Blog

- Robert Viking O'Brien & Stephen Kent O'Brien, Discovery of Guiana essay, Yearbook of Comparative and General Literature

- Sir Walter Raleigh portal at luminarium.org

- Tytler, Patrick Fraser (1848). "Life of Sir Walter Raleigh, Founded on Authentic and Original Documents". London: T. Nelson and Sons (published 1853). Retrieved 17 August 2008.

Texts by Raleigh

- Works by Walter Raleigh at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Walter Raleigh at Internet Archive

- Works by Walter Raleigh at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The History of the World Hathi Trust

- Worldly Wisdom from The Historie of the World

| Court offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Earl of Bedford |

Lord Warden of the Stannaries 1584–1603 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Pembroke |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by Sir Francis Godolphin Sir William Mohun Peter Edgcumbe Richard Carew |

Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall 1587–1603 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Pembroke |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Edward Seymour |

Vice-Admiral of Devon 1585–1603 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Bath (North Devon) and Sir Richard Hawkins (South Devon) |

| Preceded by John Best |

Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard 1597–1603 |

Succeeded by Sir Thomas Erskine |

| Preceded by Sir Matthew Arundell |

Custos Rotulorum of Dorset 1598–1603 |

Succeeded by Viscount Howard of Bindon |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Anthony Paulet |

Governor of Jersey 1600–1603 |

Succeeded by Sir John Peyton |

|