Microsatellite

A microsatellite is a tract of repetitive DNA in which certain DNA motifs (ranging in length from 2–5 base pairs) are repeated, typically 5-50 times.[1] Microsatellites occur at thousands of locations in the human genome and they are notable for their high mutation rate and high diversity in the population.

Microsatellites and their longer cousins, the minisatellites, together are classified as VNTR (variable number of tandem repeats) DNA. The name "satellite" refers to the early observation that centrifugation of genomic DNA in a test tube separates a prominent layer of bulk DNA from accompanying "satellite" layers of repetitive DNA. Microsatellites are often referred to as short tandem repeats (STRs) by forensic geneticists, or as simple sequence repeats (SSRs) by plant geneticists.

They are widely used for DNA profiling in kinship analysis and in forensic identification. They are also used in genetic linkage analysis/marker assisted selection to locate a gene or a mutation responsible for a given trait or disease.

Structures and Locations

A microsatellite consists of a tract of tandemly repeated (i.e. adjacent) DNA motifs that range in length from two to five nucleotides, and are typically repeated 5-50 times. For example, the sequence TATATATATA is a dinucleotide microsatellite, and GTCGTCGTCGTCGTC is a trinucleotide microsatellite (with A being Adenine, G Guanine, C Cytosine, and T Thymine). Repeat units of four and five nucleotides are referred to as tetra- and pentanucleotide motifs, respectively.

The telomeres at the ends of the chromosomes, thought to be involved in ageing/senescence, consist of repetitive DNA, with the hexanucleotide repeat motif TTAGGG in vertebrates. They are thus classified as minisatellites, although insects for example have shorter repeat motifs in their telomeres which therefore could arguably be considered microsatellites.

Microsatellites are distributed throughout the genome.[2][3] Many are located in non-coding parts of the human genome and are therefore biologically silent. This allows them to accumulate mutations unhindered over the generations and gives rise to variability which can be used for DNA fingerprinting and identification purposes. Other microsatellites are located in regulatory flanking or intronic regions of genes, or directly in codons of genes - microsatellite mutations in such cases can lead to phenotypic changes and diseases, notably in triplet expansion diseases such as fragile X syndrome and Huntington's disease.

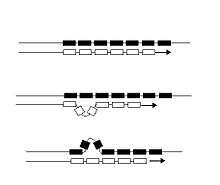

Mutation mechanism

Unlike point mutations which affect only a single nucleotide, microsatellite mutations lead to the gain or loss of an entire repeat unit, and sometimes two or more repeats simultaneously. The proposed cause of such length changes is replication slippage, caused by mismatches between DNA strands while being replicated during meiosis,[4] and this proposed mechanism has received some experimental verification.[5][6] Typically, slippage in each microsatellite occurs about once per 1,000 generations.[7] Thus, slippage changes in repetitive DNA are three orders of magnitude more common than point mutations in other parts of the genome.[8] Most slippage results in a change of just one repeat unit, and slippage rates vary for different repeat unit sizes, and within different species.[9]

Biological effects of microsatellite mutations

Many microsatellites are located in non-coding DNA and are biologically silent. Others are located in regulatory or even coding DNA - microsatellite mutations in such cases can lead to phenotypic changes and diseases. Recent studies provided evidence that microsatellites may act as enhancers regulating disease-relevant genes.[10][11]

Effects on proteins

In mammals, 20% to 40% of proteins contain repeating sequences of amino acids encoded by short sequence repeats.[12] Most of the short sequence repeats within protein-coding portions of the genome have a repeating unit of three nucleotides, since that length will not cause frame-shifts when mutating.[13] Each trinucleotide repeating sequence is transcribed into a repeating series of the same amino acid. In yeasts, the most common repeated amino acids are glutamine, glutamic acid, asparagine, aspartic acid and serine.

Mutations in these repeating segments can affect the physical and chemical properties of proteins, with the potential for producing gradual and predictable changes in protein action.[14] For example, length changes in tandemly repeating regions in the Runx2 gene lead to differences in facial length in domesticated dogs (Canis familiaris), with an association between longer sequence lengths and longer faces.[15] This association also applies to a wider range of Carnivora species.[16] Length changes in polyalanine tracts within the HoxA13 gene are linked to Hand-Foot-Genital Syndrome, a developmental disorder in humans.[17] Length changes in other triplet repeats are linked to more than 40 neurological diseases in humans.[18] Evolutionary changes from replication slippage also occur in simpler organisms. For example, microsatellite length changes are common within surface membrane proteins in yeast, providing rapid evolution in cell properties.[19] Specifically, length changes in the FLO1 gene control the level of adhesion to substrates.[20] Short sequence repeats also provide rapid evolutionary change to surface proteins in pathenogenic bacteria; this may allow them to keep up with immunological changes in their hosts.[21] Length changes in short sequence repeats in a fungus (Neurospora crassa) control the duration of its circadian clock cycles.[22]

Effects on gene regulation

Length changes of microsatellites within promoters and other cis-regulatory regions can also change gene expression quickly, between generations. The human genome contains many (>16,000) short sequence repeats in regulatory regions, which provide ‘tuning knobs’ on the expression of many genes.[10][23]

Length changes in bacterial SSRs can affect fimbriae formation in Haemophilus influenza, by altering promoter spacing.[21] Minisatellites are also linked to abundant variations in cis-regulatory control regions in the human genome.[23] And microsatellites in control regions of the Vasopressin 1a receptor gene in voles influence their social behavior, and level of monogamy.[24]

Effects within introns

Microsatellites within introns also influence phenotype, through means that are not currently understood. For example, a GAA triplet expansion in the first intron of the X25 gene appears to interfere with transcription, and causes Friedreich Ataxia.[25] Tandem repeats in the first intron of the Asparagine synthetase gene are linked to acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.[26] A repeat polymorphism in the fourth intron of the NOS3 gene is linked to hypertension in a Tunisian population.[27] Reduced repeat lengths in the EGFR gene are linked with osteosarcomas.[28]

Effects within transposons

Almost 50% of the human genome is contained in various types of transposable elements (also called transposons, or ‘jumping genes’), and many of them contain repetitive DNA.[29] It is probable that short sequence repeats in those locations are also involved in the regulation of gene expression.[30]

Analysis of microsatellites

Microsatellites are widely used for DNA profiling in kinship analysis (most commonly in paternity testing) and in forensic identification (typically matching a crime stain to a victim or perpetrator). Also, microsatellites are used for mapping locations within the genome, specifically in genetic linkage analysis/marker assisted selection to locate a gene or a mutation responsible for a given trait or disease. As a special case of mapping, they can be used for studies of gene duplication or deletion. These applications are realised by various technical methods.

Amplification

Microsatellites can be amplified for identification by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) process, using the unique sequences of flanking regions as primers. DNA is repeatedly denatured at a high temperature to separate the double strand, then cooled to allow annealing of primers and the extension of nucleotide sequences through the microsatellite. This process results in production of enough DNA to be visible on agarose or polyacrylamide gels; only small amounts of DNA are needed for amplification because in this way thermocycling creates an exponential increase in the replicated segment.[31] With the abundance of PCR technology, primers that flank microsatellite loci are simple and quick to use, but the development of correctly functioning primers is often a tedious and costly process.

Design of microsatellite primers

If searching for microsatellite markers in specific regions of a genome, for example within a particular exon of a gene, primers can be designed manually. This involves searching the genomic DNA sequence for microsatellite repeats, which can be done by eye or by using automated tools such as repeat masker. Once the potentially useful microsatellites are determined, the flanking sequences can be used to design oligonucleotide primers which will amplify the specific microsatellite repeat in a PCR reaction.

Random microsatellite primers can be developed by cloning random segments of DNA from the focal species. These random segments are inserted into a plasmid or bacteriophage vector, which is in turn implanted into Escherichia coli bacteria. Colonies are then developed, and screened with fluorescently–labelled oligonucleotide sequences that will hybridize to a microsatellite repeat, if present on the DNA segment. If positive clones can be obtained from this procedure, the DNA is sequenced and PCR primers are chosen from sequences flanking such regions to determine a specific locus. This process involves significant trial and error on the part of researchers, as microsatellite repeat sequences must be predicted and primers that are randomly isolated may not display significant polymorphism.[8][32] Microsatellite loci are widely distributed throughout the genome and can be isolated from semi-degraded DNA of older specimens, as all that is needed is a suitable substrate for amplification through PCR.

More recent techniques involve using oligonucleotide sequences consisting of repeats complementary to repeats in the microsatellite to "enrich" the DNA extracted (Microsatellite enrichment). The oligonucleotide probe hybridizes with the repeat in the microsatellite, and the probe/microsatellite complex is then pulled out of solution. The enriched DNA is then cloned as normal, but the proportion of successes will now be much higher, drastically reducing the time required to develop the regions for use. However, which probes to use can be a trial and error process in itself.[33]

ISSR-PCR

ISSR (for inter-simple sequence repeat) is a general term for a genome region between microsatellite loci. The complementary sequences to two neighboring microsatellites are used as PCR primers; the variable region between them gets amplified. The limited length of amplification cycles during PCR prevents excessive replication of overly long contiguous DNA sequences, so the result will be a mix of a variety of amplified DNA strands which are generally short but vary much in length.

Sequences amplified by ISSR-PCR can be used for DNA fingerprinting. Since an ISSR may be a conserved or nonconserved region, this technique is not useful for distinguishing individuals, but rather for phylogeography analyses or maybe delimiting species; sequence diversity is lower than in SSR-PCR, but still higher than in actual gene sequences. In addition, microsatellite sequencing and ISSR sequencing are mutually assisting, as one produces primers for the other.

Limitations

Microsatellites have proven to be versatile molecular markers, particularly for population analysis, but they are not without limitations. Microsatellites developed for particular species can often be applied to closely related species, but the percentage of loci that successfully amplify may decrease with increasing genetic distance.[8] Point mutation in the primer annealing sites in such species may lead to the occurrence of ‘null alleles’, where microsatellites fail to amplify in PCR assays.[8][34] Null alleles can be attributed to several phenomena. Sequence divergence in flanking regions can lead to poor primer annealing, especially at the 3’ section, where extension commences; preferential amplification of particular size alleles due to the competitive nature of PCR can lead to heterozygous individuals being scored for homozygosity (partial null). PCR failure may result when particular loci fail to amplify, whereas others amplify more efficiently and may appear homozygous on a gel assay, when they are in reality heterozygous in the genome. Null alleles complicate the interpretation of microsatellite allele frequencies and thus make estimates of relatedness faulty. Furthermore, stochastic effects of sampling that occurs during mating may change allele frequencies in a way that is very similar to the effect of null alleles; an excessive frequency of homozygotes causing deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium expectations. Since null alleles are a technical problem and sampling effects that occur during mating are a real biological property of a population, it is often very important to distinguish between them if excess homozygotes are observed.

When using microsatellites to compare species, homologous loci may be easily amplified in related species, but the number of loci that amplify successfully during PCR may decrease with increased genetic distance between the species in question. Mutation in microsatellite alleles is biased in the sense that larger alleles contain more bases, and are therefore likely to be mistranslated in DNA replication. Smaller alleles also tend to increase in size, whereas larger alleles tend to decrease in size, as they may be subject to an upper size limit; this constraint has been determined but possible values have not yet been specified. If there is a large size difference between individual alleles, then there may be increased instability during recombination at meiosis.[8] In tumour cells, where controls on replication may be damaged, microsatellites may be gained or lost at an especially high frequency during each round of mitosis. Hence a tumour cell line might show a different genetic fingerprint from that of the host tissue.

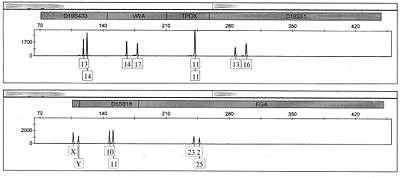

Forensic analysis

Microsatellite analysis became popular in the field of forensics in the 1990s. It is used for the genetic fingerprinting of individuals. The microsatellites in use today for forensic analysis are all tetra- or penta-nucleotide repeats, as these give a high degree of error-free data while being robust enough to survive degradation in non-ideal conditions. Shorter repeat sequences tend to suffer from artifacts such as PCR stutter and preferential amplification, as well as the fact that several genetic diseases are associated with tri-nucleotide repeats such as Huntington's disease. Longer repeat sequences will suffer more highly from environmental degradation and do not amplify by PCR as well as shorter sequences.[35]

The analysis is performed by extracting nuclear DNA from the cells of a forensic sample of interest, then amplifying specific polymorphic regions of the extracted DNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Once these sequences have been amplified, they are resolved either through gel electrophoresis or capillary electrophoresis, which will allow the analyst to determine how many repeats of the microsatellites sequence in question there are. If the DNA was resolved by gel electrophoresis, the DNA can be visualized either by silver staining (low sensitivity, safe, inexpensive), or an intercalating dye such as ethidium bromide (fairly sensitive, moderate health risks, inexpensive), or as most modern forensics labs use, fluorescent dyes (highly sensitive, safe, expensive).[36] Instruments built to resolve microsatellite fragments by capillary electrophoresis also use fluorescent dyes.[36] It is also used to follow up bone marrow transplant patients.[37] In the United States, 13 core microsatellite loci have been decided upon to be the basis by which an individual genetic profile can be generated.[38]

These profiles are stored on a local, state and national level in DNA databanks such as CODIS. The British data base for microsatellite loci identification is the UK National DNA Database (NDNAD). The British SGM+ system[39][40] uses 10 loci and a sex marker, rather than the American[41] 13 loci.

Y-STRs (microsatellites on the Y chromosome) are often used in genealogical DNA testing.

See also

- Genetic marker

- Junk DNA

- Long interspersed repetitive element

- Microsatellite instability

- Minisatellite

- Mobile element

- Satellite DNA

- Short interspersed repetitive element

- Simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP)

- Snpstr

- Transposon

- Trinucleotide repeat disorders

References

- ↑ Turnpenny P, Ellard S (2005). Emery's Elements of Medical Genetics, 12th. ed. London: Elsevier.

- ↑ King D. G.; Soller, Morris; Kashi, Yechezkel (1997). "Evolutionary tuning knobs". Endeavor 21: 36–40. doi:10.1016/S0160-9327(97)01005-3.

- ↑ Richard G-F.; et al. (2008). "Comparative genomics and molecular dynamics of DNA repeats in Eukaryotes". Micr. Mol. Bio. Rev 72 (4): 686–727. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00011-08. PMC 2593564. PMID 19052325.

- ↑ Tautz D., Schlötterer C. (1994). "Simple sequences". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 4 (6): 832–837. doi:10.1016/0959-437X(94)90067-1. PMID 7888752.

- ↑ Klintschar M, et al. (2004). "Haplotype studies support slippage as the mechanism of germline mutations in short tandem repeats". Electrophoresis 25: 3344–3348. doi:10.1002/elps.200406069. PMID 15490457.

- ↑ Forster P., Hohoff C., Dunkelmann B., Schürenkamp M., Pfeiffer H., Neuhuber F., Brinkmann B. (2015). "Elevated germline mutation rate in teenage fathers". Proc. R. Soc. B. 282 (1803): 20142898. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2898. PMC 4345458. PMID 25694621.

- ↑ Weber J.L., Wong C. (1993). "Mutation of human short tandem repeats". Hum. Mol. Genet. 2 (8): 1123–1128. doi:10.1093/hmg/2.8.1123. PMID 8401493.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jarne P., Lagoda P. J. L. (1996). "Microsatellites, from molecules to populations and back". Trends Ecol. Evol 11 (10): 424–429. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10049-5. PMID 21237902.

- ↑ Kruglyak S, et al. (1998). "Equilibrium distributions of microstellite repeat length resulting from a balance between slippage events and point mutations". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (18): 10774–10778. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9510774K. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.18.10774. PMC 27971. PMID 9724780.

- 1 2 Gymrek, Melissa; Willems, Thomas; Guilmatre, Audrey; Zeng, Haoyang; Markus, Barak; Georgiev, Stoyan; Daly, Mark J; Price, Alkes L; Pritchard, Jonathan K. "Abundant contribution of short tandem repeats to gene expression variation in humans". Nature Genetics 48: 22–29. doi:10.1038/ng.3461.

- ↑ Grünewald, Thomas G P; Bernard, Virginie; Gilardi-Hebenstreit, Pascale; Raynal, Virginie; Surdez, Didier; Aynaud, Marie-Ming; Mirabeau, Olivier; Cidre-Aranaz, Florencia; Tirode, Franck. "Chimeric EWSR1-FLI1 regulates the Ewing sarcoma susceptibility gene EGR2 via a GGAA microsatellite". Nature Genetics 47 (9): 1073–1078. doi:10.1038/ng.3363. PMC 4591073. PMID 26214589.

- ↑ Marcotte E. M.; et al. (1998). "A census of protein repeats". J. Mol. Biol. 293 (1): 151–160. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3136. PMID 10512723.

- ↑ Sutherland G. R., Richards R. I.; Richards (1995). "Simple tandem DNA repeats and human genetic disease". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (9): 3636–3641. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.3636S. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.9.3636. PMC 42017. PMID 7731957.

- ↑ Hancock J. M., Simon M. (2005). "Simple sequence repeats in proteins and their significance for network evolution". Gene 345 (1): 113–118. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2004.11.023. PMID 15716087.

- ↑ Fondon J. W. III, Garner H. R.; Garner (2004). "Molecular origins of rapid and continuous morphological evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1010 (52): 18058–18063. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10118058F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408118101.

- ↑ Sears K. E.; et al. (2007). "The correlated evolution of Runx2 tandem repeats, transcriptional activity, and facial length in Carnivora". Evol. & Dev 9 (6): 555–565. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00196.x.

- ↑ Utsch B, et al. (2002). "A novel stable stable polyalanine [poly(A)] expansion in the HoxA13 gene associated with hand-foot-genital syndrome: proper function of poly(A)-harbouring transcription factors depends on a critical repeat length?". Hum. Gen 110 (5): 488–494. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0712-8. PMID 12073020.

- ↑ Pearson C. E.; et al. (2005). "Repeat instability: mechanisms of dynamic mutations". Nature Reviews Genetics 6 (10): 729–742. doi:10.1038/nrg1689.

- ↑ Bowen S., Wheals A. E. (2006). "Ser//Thr-rich domains are associated with genetic variation and morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Yeast 23 (8): 633–640. doi:10.1002/yea.1381. PMID 16823884.

- ↑ Verstrepen K. J.; et al. (2005). "Intragenic tandem repeats generate functional variability". Nat. Genet. 37 (9): 986–990. doi:10.1038/ng1618.

- 1 2 Moxon E. R.; et al. (1994). "Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria". Curr. Bio 4: 24–32. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00005-1.

- ↑ Michael T. P.; et al. (2007). Redfield, Rosemary, ed. "Simple sequence repeats provide a substrate for phenotypic variation in the Neurospora crassa circadian clock". PLoS ONE 2 (8): e795. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..795M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000795.

- 1 2 Rockman M. V., Wray G. A. (2002). "Abundant raw material for cis-regulatory evolution in humans". Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 (11): 1991–2004. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004023. PMID 12411608.

- ↑ Hammock E. A. D., Young L. J.; Young (2005). "Microsatellite instability generates diversity in brain and sociobehavioral traits". Science 308 (5728): 1630–1634. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1630H. doi:10.1126/science.1111427. PMID 15947188.

- ↑ Bidichandani S. I.; et al. (1998). "The GAA triplet-repeat expansion in Friedreich ataxia interferes with transcription and may be associated with an unusual DNA structure". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 62 (1): 111–121. doi:10.1086/301680. PMC 1376805. PMID 9443873.

- ↑ Akagi T, et al. (2008). "Functional analysis of a novel DNA polymorphism of a tandem repeated sequence in the asparagine synthetase gene in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells". Leuk. Res. 33 (7): 991–996. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2008.10.022. PMC 2731768. PMID 19054556.

- ↑ Jemaa R, et al. (2008). "Association of a 27-bp repeat polymorphism in intron 4 of endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase gene with hypertension in a Tunisian population". Clin. Biochem 42 (9): 852–856. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.12.002. PMID 19111531.

- ↑ Kersting C, et al. (2008). "Biological importance of a polymorphic CA sequence within intron I of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene (EGFR) in high grade central osteosarcomas". Gene Chrom. & Cancer 47 (8): 657–664. doi:10.1002/gcc.20571.

- ↑ Scherer S. (2008). A short guide to the human genome. New York: Cold Spring Harbor University Press.

- ↑ Tomilin N. V. (2008). "Regulation of mammalian gene expression by retroelements and non-coding tandem repeats". BioEssays 30 (4): 338–348. doi:10.1002/bies.20741. PMID 18348251.

- ↑ Griffiths, A.J.F., Miller, J.F., Suzuki, D.T., Lewontin, R.C. & Gelbart, W.M. (1996). Introduction to Genetic Analysis, 5th Edition. W.H. Freeman, New York.

- ↑ Queller, D.C., Strassman,,J.E. & Hughes, C.R. (1993). "Microsatellites and Kinship". Trends in Ecology and Evolution 8 (8): 285–288. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(93)90256-O. PMID 21236170.

- ↑ Kaukinen KH, Supernault KJ, and Miller KM (2004). "Enrichment of tetranucleotide microsatellite loci from invertebrate species". Journal of Shellfish Research 23 (2): 621.

- ↑ Dakin, EE; Avise, JC (2004). "Microsatellite null alleles in parentage analysis". Heredity 93 (5): 504–509. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800545. PMID 15292911.

- ↑ Angel Carracedo. "DNA Profiling". Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- 1 2 "Technology for Resolving STR Alleles". Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ Antin JH, Childs R, Filipovich AH, et al. (2001). "Establishment of complete and mixed donor chimerism after allogeneic lymphohematopoietic transplantation: recommendations from a workshop at the 2001 Tandem Meetings of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation". Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 7 (9): 473–85. doi:10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11669214. PMID 11669214.

- ↑ Butler J.M. (2005). Forensic DNA Typing: Biology, Technology, and Genetics of STR Markers, Second Edition. New York: Elsevier Academic Press.

- ↑ "The National DNA Database" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ "House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology Written Evidence". Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ "FBI CODIS Core STR Loci". Retrieved 2010-09-20.

Further Literature

- Caporale L. H. (2003). "Natural selection and the emergence of a mutation phenotype: an update of the evolutionary synthesis considering mechanisms that affect genome variation". Ann. Rev. Micro 57: 467–485. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090855.

- Kashi Y, et al. (1997). "Simple sequence repeats as a source of quantitative genetic variation". Trends Gen 13 (2): 74–78. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01008-1.

- Kinoshita Y, et al. (2007). "Control of FWA gene silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana by SINE-related direct repeats". Plant. J. 49 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02936.x. PMID 17144899.

- Li Y-C.; et al. (2002). "Microsatellites: genomic distribution, putative functions and mutational mechanisms: a review". Mol. Ecol 11 (12): 2453–2465. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01643.x. PMID 12453231.

- Li Y-C.; et al. (2003). "Microsatellites within genes: structure, function and evolution". Mol. Bio. Evol 21 (6): 991–1007. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh073. PMID 14963101.

- Mattick J. S. (2003). "Challenging the dogma: the hidden layer of non-protein-coding RNAs in complex organisms". BioEssays 25 (10): 930–939. doi:10.1002/bies.10332. PMID 14505360.

- Meagher T., Vassiliadis C. (2005). "Phenotypic impacts of repetitive DNA in flowering plants". New Phyto 168: 71–80. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01527.x.

- Müller K. J.; Romano; Gerstner; Garcia-Marotot; Pozzi; Salamini; Rohde; et al. (1995). "The barley Hooded mutation caused by a duplication in a homeobox gene intron". Nature 374 (6524): 727–730. Bibcode:1995Natur.374..727M. doi:10.1038/374727a0. PMID 7715728.

- Pumpernik D, et al. ", Replication slippage versus point mutation rates in short tandem repeats of the human genome. 2008. Mol. Genet". Genomics 279 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1007/s00438-007-0294-1.

- Streelman J. T., Kocher T. D. (2002). "Microsatellite variation associated with prolactin expression and growth of salt-challenged Tilapia". Phys. Genom 9: 1–4.

- Vinces M. D.; Legendre; Caldara; Hagihara; Verstrepen; et al. (2009). "Unstable tandem repeats in promoters confer transcriptional evolvability". Science 324 (5931): 1213–1216. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1213V. doi:10.1126/science.1170097. PMC 3132887. PMID 19478187.

External links

- About microsatellites:

- Search tools :

- SSR Finder

- Imperfect SSR Finder - find perfect or imperfect SSRs in FASTA sequences.

- JSTRING - Java Search for Tandem Repeats in genomes

- Microsatellite repeats finder

- MISA - MIcroSAtellite identification tool

- MREPATT

- Mreps

- IMEx

- FireMuSat2+

- Phobos - a tandem repeat search tool for perfect and imperfect repeats - the maximum pattern size depends only on computational power

- Poly

- Tandem Repeats Finder

- STAR

- TandemSWAN

- TRED

- TROLL

- SciRoKo

- SSLP

- Zebrafish Repeats

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||