Signal-to-noise ratio

| Part of a series on |

| Antennas |

|---|

|

|

Common types |

|

Radiation sources / regions |

Signal-to-noise ratio (abbreviated SNR or S/N) is a measure used in science and engineering that compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. It is defined as the ratio of signal power to the noise power, often expressed in decibels. A ratio higher than 1:1 (greater than 0 dB) indicates more signal than noise. While SNR is commonly quoted for electrical signals, it can be applied to any form of signal (such as isotope levels in an ice core or biochemical signaling between cells).

The signal-to-noise ratio, the bandwidth, and the channel capacity of a communication channel are connected by the Shannon–Hartley theorem.

Signal-to-noise ratio is sometimes used informally to refer to the ratio of useful information to false or irrelevant data in a conversation or exchange. For example, in online discussion forums and other online communities, off-topic posts and spam are regarded as "noise" that interferes with the "signal" of appropriate discussion.[1]

Definition

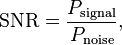

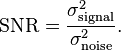

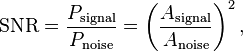

Signal-to-noise ratio is defined as the ratio of the power of a signal (meaningful information) and the power of background noise (unwanted signal):

where P is average power. Both signal and noise power must be measured at the same or equivalent points in a system, and within the same system bandwidth.

If the variance of the signal and noise are known, and the signal is zero-mean:[2]

If the signal and the noise are measured across the same impedance, then the SNR can be obtained by calculating the square of the amplitude ratio:

where A is root mean square (RMS) amplitude (for example, RMS voltage).

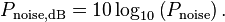

Decibels

Because many signals have a very wide dynamic range, signals are often expressed using the logarithmic decibel scale. Based upon the definition of decibel, signal and noise may be expressed in decibels (dB) as

and

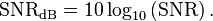

In a similar manner, SNR may be expressed in decibels as

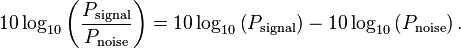

Using the definition of SNR

Using the quotient rule for logarithms

Substituting the definitions of SNR, signal, and noise in decibels into the above equation results in an important formula for calculating the signal to noise ratio in decibels, when the signal and noise are also in decibels:

In the above formula, P is measured in units of power, such as Watts or miliWatts, and signal-to-noise ratio is a pure number.

However, when the signal and noise are measured in Volts or Amperes, which are measures of amplitudes, they must be squared to be proportionate to power as shown below:

Dynamic range

The concepts of signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range are closely related. Dynamic range measures the ratio between the strongest un-distorted signal on a channel and the minimum discernible signal, which for most purposes is the noise level. SNR measures the ratio between an arbitrary signal level (not necessarily the most powerful signal possible) and noise. Measuring signal-to-noise ratios requires the selection of a representative or reference signal. In audio engineering, the reference signal is usually a sine wave at a standardized nominal or alignment level, such as 1 kHz at +4 dBu (1.228 VRMS).

SNR is usually taken to indicate an average signal-to-noise ratio, as it is possible that (near) instantaneous signal-to-noise ratios will be considerably different. The concept can be understood as normalizing the noise level to 1 (0 dB) and measuring how far the signal 'stands out'.

Difference from conventional power

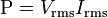

In physics, the average power of an AC signal is defined as the average value of voltage times current; for resistive (non-reactive) circuits, where voltage and current are in phase, this is equivalent to the product of the rms voltage and current:

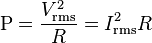

But in signal processing and communication, one usually assumes that  so that factor is usually not included while measuring power or energy of a signal. This may cause some confusion among readers, but the resistance factor is not significant for typical operations performed in signal processing, or for computing power ratios. For most cases, the power of a signal would be considered to be simply

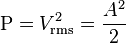

so that factor is usually not included while measuring power or energy of a signal. This may cause some confusion among readers, but the resistance factor is not significant for typical operations performed in signal processing, or for computing power ratios. For most cases, the power of a signal would be considered to be simply

where 'A' is the amplitude of the AC signal.

Alternative definition

An alternative definition of SNR is as the reciprocal of the coefficient of variation, i.e., the ratio of mean to standard deviation of a signal or measurement:[4][5]

where  is the signal mean or expected value and

is the signal mean or expected value and  is the standard deviation of the noise, or an estimate thereof.[note 2] Notice that such an alternative definition is only useful for variables that are always non-negative (such as photon counts and luminance). Thus it is commonly used in image processing,[6][7][8][9] where the SNR of an image is usually calculated as the ratio of the mean pixel value to the standard deviation of the pixel values over a given neighborhood. Sometimes SNR is defined as the square of the alternative definition above.

is the standard deviation of the noise, or an estimate thereof.[note 2] Notice that such an alternative definition is only useful for variables that are always non-negative (such as photon counts and luminance). Thus it is commonly used in image processing,[6][7][8][9] where the SNR of an image is usually calculated as the ratio of the mean pixel value to the standard deviation of the pixel values over a given neighborhood. Sometimes SNR is defined as the square of the alternative definition above.

The Rose criterion (named after Albert Rose) states that an SNR of at least 5 is needed to be able to distinguish image features at 100% certainty. An SNR less than 5 means less than 100% certainty in identifying image details.[5][10]

Yet another alternative, very specific and distinct definition of SNR is employed to characterize sensitivity of imaging systems; see Signal-to-noise ratio (imaging).

Related measures are the "contrast ratio" and the "contrast-to-noise ratio".

SNR for various modulation systems

Amplitude modulation

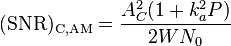

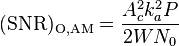

Channel signal-to-noise ratio is given by

where W is the bandwidth and  is modulation index

is modulation index

Output signal-to-noise ratio (of AM receiver) is given by

Frequency modulation

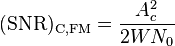

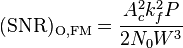

Channel signal-to-noise ratio is given by

Output signal-to-noise ratio is given by

Improving SNR in practice

All real measurements are disturbed by noise. This includes electronic noise, but can also include external events that affect the measured phenomenon — wind, vibrations, gravitational attraction of the moon, variations of temperature, variations of humidity, etc., depending on what is measured and of the sensitivity of the device. It is often possible to reduce the noise by controlling the environment. Otherwise, when the characteristics of the noise are known and are different from the signals, it is possible to filter it or to process the signal.

For example, it is sometimes possible to use a lock-in amplifier to modulate and confine the signal within a very narrow bandwidth and then filter the detected signal to the narrow band where it resides, thereby eliminating most of the broadband noise. When the signal is constant or periodic and the noise is random, it is possible to enhance the SNR by averaging the measurement. In this case the noise goes down as the square root of the number of averaged samples.

Digital signals

When a measurement is digitized, the number of bits used to represent the measurement determines the maximum possible signal-to-noise ratio. This is because the minimum possible noise level is the error caused by the quantization of the signal, sometimes called Quantization noise. This noise level is non-linear and signal-dependent; different calculations exist for different signal models. Quantization noise is modeled as an analog error signal summed with the signal before quantization ("additive noise").

This theoretical maximum SNR assumes a perfect input signal. If the input signal is already noisy (as is usually the case), the signal's noise may be larger than the quantization noise. Real analog-to-digital converters also have other sources of noise that further decrease the SNR compared to the theoretical maximum from the idealized quantization noise, including the intentional addition of dither.

Although noise levels in a digital system can be expressed using SNR, it is more common to use Eb/No, the energy per bit per noise power spectral density.

The modulation error ratio (MER) is a measure of the SNR in a digitally modulated signal.

Fixed point

For n-bit integers with equal distance between quantization levels (uniform quantization) the dynamic range (DR) is also determined.

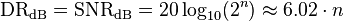

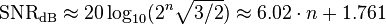

Assuming a uniform distribution of input signal values, the quantization noise is a uniformly distributed random signal with a peak-to-peak amplitude of one quantization level, making the amplitude ratio 2n/1. The formula is then:

This relationship is the origin of statements like "16-bit audio has a dynamic range of 96 dB". Each extra quantization bit increases the dynamic range by roughly 6 dB.

Assuming a full-scale sine wave signal (that is, the quantizer is designed such that it has the same minimum and maximum values as the input signal), the quantization noise approximates a sawtooth wave with peak-to-peak amplitude of one quantization level[11] and uniform distribution. In this case, the SNR is approximately

Floating point

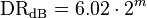

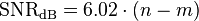

Floating-point numbers provide a way to trade off signal-to-noise ratio for an increase in dynamic range. For n bit floating-point numbers, with n-m bits in the mantissa and m bits in the exponent:

Note that the dynamic range is much larger than fixed-point, but at a cost of a worse signal-to-noise ratio. This makes floating-point preferable in situations where the dynamic range is large or unpredictable. Fixed-point's simpler implementations can be used with no signal quality disadvantage in systems where dynamic range is less than 6.02m. The very large dynamic range of floating-point can be a disadvantage, since it requires more forethought in designing algorithms.[12]

Optical SNR

Optical signals have a carrier frequency that is much higher than the modulation frequency (about 200 THz and more). This way the noise covers a bandwidth that is much wider than the signal itself. The resulting signal influence relies mainly on the filtering of the noise. To describe the signal quality without taking the receiver into account, the optical SNR (OSNR) is used. The OSNR is the ratio between the signal power and the noise power in a given bandwidth. Most commonly a reference bandwidth of 0.1 nm is used. This bandwidth is independent of the modulation format, the frequency and the receiver. For instance an OSNR of 20dB/0.1 nm could be given, even the signal of 40 GBit DPSK would not fit in this bandwidth. OSNR is measured with an optical spectrum analyzer.

Types and abbreviations

Signal to noise ratio may be abbreviated as SNR and less commonly as S/N. PSNR stands for Peak signal-to-noise ratio. GSNR stands for Geometric Signal-to-Noise Ratio. SINR is the Signal-to-noise-plus-interference ratio.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The connection between optical power and voltage in an imaging system is linear. This usually means that the SNR of the electrical signal is calculated by the 10 log rule. With an interferometric system, however, where interest lies in the signal from one arm only, the field of the electromagnetic wave is proportional to the voltage (assuming that the intensity in the second, the reference arm is constant). Therefore the optical power of the measurement arm is directly proportional to the electrical power and electrical signals from optical interferometry are following the 20 log rule.[3]

- ↑ The exact methods may vary between fields. For example, if the signal data are known to be constant, then

can be calculated using the standard deviation of the signal. If the signal data are not constant, then

can be calculated using the standard deviation of the signal. If the signal data are not constant, then  can be calculated from data where the signal is zero or relatively constant.

can be calculated from data where the signal is zero or relatively constant. - ↑ Often special filters are used to weight the noise: DIN-A, DIN-B, DIN-C, DIN-D, CCIR-601; for video, special filters such as comb filters may be used.

- ↑ Maximum possible full scale signal can be charged as peak-to-peak or as RMS. Audio uses RMS, Video P-P, which gave +9 dB more SNR for video.

References

- ↑ Breeding, Andy (2004). The Music Internet Untangled: Using Online Services to Expand Your Musical Horizons. Giant Path. p. 128. ISBN 9781932340020.

- ↑ "Signal-to-noise ratio". scholarpedia.org.

- ↑ Michael A. Choma, Marinko V. Sarunic, Changhuei Yang, Joseph A. Izatt. Sensitivity advantage of swept source and Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Express, 11(18). Sept 2003.

- ↑ D. J. Schroeder (1999). Astronomical optics (2nd ed.). Academic Press. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-12-629810-9.

- 1 2 Bushberg, J. T., et al., The Essential Physics of Medical Imaging, (2e). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006, p. 280.

- ↑ Rafael C. González, Richard Eugene Woods (2008). Digital image processing. Prentice Hall. p. 354. ISBN 0-13-168728-X.

- ↑ Tania Stathaki (2008). Image fusion: algorithms and applications. Academic Press. p. 471. ISBN 0-12-372529-1.

- ↑ Jitendra R. Raol (2009). Multi-Sensor Data Fusion: Theory and Practice. CRC Press. ISBN 1-4398-0003-0.

- ↑ John C. Russ (2007). The image processing handbook. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-7254-2.

- ↑ Rose, Albert (1973). Vision - Human and Electronic. Plenum Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780306307324.

[...] to reduce the number of false alarms to below unity, we will need [...] a signal whose amplitude is 4-5 times larger than the rms noise.

- ↑ Defining and Testing Dynamic Parameters in High-Speed ADCs — Maxim Integrated Products Application note 728

- ↑ Fixed-Point vs. Floating-Point DSP for Superior Audio — Rane Corporation technical library

External links

- Taking the Mystery out of the Infamous Formula,"SNR = 6.02N + 1.76dB," and Why You Should Care. Analog Devices

- ADC and DAC Glossary – Maxim Integrated Products

- Understand SINAD, ENOB, SNR, THD, THD + N, and SFDR so you don't get lost in the noise floor – Analog Devices

- The Relationship of dynamic range to data word size in digital audio processing

- Calculation of signal-to-noise ratio, noise voltage, and noise level

- Learning by simulations – a simulation showing the improvement of the SNR by time averaging

- Dynamic Performance Testing of Digital Audio D/A Converters

- Fundamental theorem of analog circuits: a minimum level of power must be dissipated to maintain a level of SNR

- Interactive webdemo of visualization of SNR in a QAM constellation diagram Institute of Telecommunicatons, University of Stuttgart

![\mathrm{SNR_{dB}} = 10 \log_{10} \left [ \left ( \frac{A_\mathrm{signal}}{A_\mathrm{noise}} \right )^2 \right ] = 20 \log_{10} \left ( \frac{A_\mathrm{signal}}{A_\mathrm{noise}} \right ) = \left ( {A_\mathrm{signal,dB} - A_\mathrm{noise,dB}}\right ).](../I/m/7e69d645ed73b91f72cb4951f404a69b.png)