Wukan protests

| Wukan protests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Villagers confront riot police in Wukan, 11 December 2011 | |||

| Date | 21–23 September 2011, December 2011 | ||

| Location |

Wukan, Lufeng, Guangdong People's Republic of China 22°53′N 115°40′E / 22.883°N 115.667°E[1]Coordinates: 22°53′N 115°40′E / 22.883°N 115.667°E[1] | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

|

| |||

Location of Wukan within China | |||

The Wukan protests, also known as the Siege of Wukan, was an anti-corruption protest that began in September 2011, and escalated in December 2011 with the expulsion of officials by villagers, the siege of the town by police, and subsequent détente[5] in the southern Chinese village of Wukan (pop. 12,000).

The protests began on 21–23 September 2011 after officials sold land to real estate developers without properly compensating the villagers. Several hundred to several thousand people protested in front of and then attacked a government building, a police station and an industrial park. Protesters held signs saying "give us back our farmland" and "let us continue farming." Rumours that the police had killed a child further inflamed the protesters and provoked rioting. Residents of Wukan had previously petitioned the national government in 2009 and 2010 over the land disputes. In an apparent attempt to ease tensions, authorities allowed villagers to select 13 representatives to engage in negotiations.

Security agents abducted five of the representatives and took them into custody in early December. The protests strengthened after one of the village representatives, Xue Jinbo, died in police custody in suspicious circumstances.[3][4] The villagers forced the entire local government, Communist Party leadership and police out of the village.[6] As of 14 December 2011, a thousand police laid siege to the village, preventing food and goods from entering the village.[5][7] Government authorities set up internet censorship against information about Wukan, Lufeng and Shanwei.[8]

Wukan is a village that had often been described as being especially harmonious.[9] International newspapers described the December uprising as being exceptional[5][6][10][11] compared to other "mass incidents" in the People's Republic of China which numbered approximately 180,000 in 2010.[12]

The village representatives and provincial officials reached a peaceful agreement, satisfying the villagers' immediate requests.[13] Local Communist Party secretary of Shanwei City said that the authority of the city has been "overridden" by provincial intervention.[14]

Background

Wukan village (population 20,000) is located in Lufeng county-level city of Guangdong province, some 5 km south (22°53′N 115°40′E / 22.883°N 115.667°E)[15] of Lufeng's central urban area. The village is near the shore of the Wukan Harbor (乌坎港), which is part of the Jieshi Bay (碣石湾) of the South China Sea;[16] the location of the village near the southern Chinese coast lends itself well to urban development.[17] The village has enjoyed the reputation on the mainland for many years as a model village for its harmoniousness, civility and prosperity.[9]

Since the abolition of agricultural taxes in 2006, local government has been increasingly raising money through land sales to the extent that this is now a primary revenue stream.[18] Conflicts between farmers and local officials have risen throughout China, often because of land seizures (or "land grabs").[18] The rate of forced evictions has grown significantly since the 1990s, as city and county-level governments have increasingly come to rely on land sales as a source of revenue. In 2011, the Financial Times reported that 40 percent of local government revenue comes from land sales.[19] Guan Qingyou, a professor at Tsinghua University, estimated that land sales accounted for 74 percent of local government income in 2010.[20] According to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, by the end of 2011 there was a total of 50 million displaced farmers across China (from all preceding years), and an average of 3 million farmers are displaced across China per year.[21] In most instances, the land is then sold to private developers at an average cost of 40 times higher per acre than the government paid to the villagers.[22]

There are more than 90,000 civil disturbances in China each year,[23] and an estimated 180,000 mass protests occurred in the country in 2010;[24] grievances are often corruption or illegal land seizures. The Jamestown Foundation offers a macroscopic explanation for the rise in conflicts: that local officials, caught between local government revenue shortfalls due to measures by central government to cool the overheated property market and their personal ratings based on their contributions to GDP growth, have resorted to undercompensating villagers for land appropriations.[25]

Farmland in Lufeng city has been progressively giving way to new developments. Projects in recent years have included a palatial new government building and a sumptuous holiday hotel resort that contained a row of 60 luxury villas. A glitzy new "Golden Sands" nightclub is a new attraction that brings rich visitors from out of town.[18] In 2011, villagers alleged local officials had grabbed hundreds of hectares of cooperative land and were "secretly selling" it to a real estate developer.[9] According to a news analysis in The New York Times, China’s village committees are elected by the villagers themselves, and are thus theoretically the most representative forms of governance, yet most residents are unfamiliar with how the village system functions, and are unaware of their rights. The sale of collectivised land is supposed to require approval of the villagers under Chinese law, and the proceeds are supposed to be shared. However, the approval process lacks transparency in practice, and most decisions are taken by the elected village committee with the blessing of the Donghai township – the level of government just above Wukan. The residents of Wukan made allegations of corruption: five of the nine members of Wukan’s village committee had held their posts since the creation of the committee system by Deng Xiaoping, and the village's Communist Party secretary, Xue Chang, has been in the position since 1970.[17]

Grievances

Residents in several villages near Wukan alleged that village officials had confiscated their farm land and sold it to developers.[9][26] The livelihoods of many were at stake: many were facing severe hardship with no land to till, and had difficulty buying food on their meagre urban incomes.[9] Wukan villagers said that they were unaware of the sale until developers began construction work, and alleged that local Communist Party officials had profited from the sale of communal land, selling it for $1 billion RMB ($156 million USD) to Country Garden.[2] Villagers asserted that 400 hectares of farmland had been appropriated without compensation since 1998.[27] The villagers petitioned various levels of government in vain over the years, accused local cadres of "pocketing more than 700 million yuan" ($110 million USD), which should legally have gone to compensating local farmers, since 2006. Local officials blamed the villagers' concerns on "troublemakers" who were manipulating those who were "unaware of the truth".[9]

September mobilisation

On the morning of 21 September 2011, hundreds of villagers participated in a sit-in protest against local officials outside government offices in Lufeng.[23] According to official statements, initially about 50 people shouting slogans and holding banners protested peacefully.[28] Protesters hoisted banners and carried placards with slogans like "give us back our farmland" and "let us continue farming".[29] Then as the crowd grew in numbers, protesters became restless and started damaging buildings and equipment in an industrial park in the village and blocking roads.[28] Policemen were dispatched, and one villager said that they severely beat some teenagers who were banging on a gong to alert fellow villagers of the protest.[9] Three villagers were arrested during the first day's violence. The next day, the police station was besieged by more than 100 villagers demanding the release of the detained villagers, and the violence escalated.[28]

The news that several youngsters had been seriously injured after being set upon by 'thugs' caused hundreds of irate villagers armed with makeshift weapons to besiege a local police station, where 30 to 40 officials were sheltering. Hundreds of well-equipped riot police were dispatched, and they engaged in a stand-off with the farmers. Video footage shot by villagers in Wukan showed people of all ages being chased and beaten with truncheons by riot police.[9] One Wukan villager described the police and other security staff as "like mad dogs, beating everyone they saw".[18] The Financial Times reported that two children, aged nine and 13, were "badly injured", and that one may have died.[2] Some villagers said that elderly people and children protesting peacefully were harassed and assaulted by "hired thugs", provoking an angry reaction from other villagers. The attacks on civilians by 400 police officers were described by the Financial Times as "indiscriminate".[2]

One of the 'hired guns' bragged that he had been brought in by an influential businessman, who paid him RMB3,000 and promised him immunity from reprisals for any assaults.[2] Officials blamed the escalating violence on "rumours" that police officers had beat a child to death. The official statement denied that any civilians had died.[23] Internet news of the riots, including photos and videos, were quickly deleted by CCP censors.[30] Press reported that searches on Sina Weibo (a microblog) for terms linked to Lufeng were blocked a short time after the protests began.[9]

On the third day of unrest, the municipality of Shanwei, which has the responsibility for Lufeng, issued a statement saying that "hundreds of villagers attacked government buildings". It said "more than a dozen police officers had been injured and '6 police vehicles had suffered damage'".[23] In what appeared to analysts as a change of tactics, observers noted that the authorities withdrew visible police presence for several days instead of stepping up police presence and suppressing the protesters more forcefully. Guangdong party chief Wang Yang also reassured residents by declaring that he was prepared to accept lower economic growth in Guangdong in exchange for increased harmony within the province.[18] Jean Pierre Cabestan, a politics professor at Hong Kong Baptist University, suspected that the policing change was due to the political aspirations of Wang, who wants to "survive and protect his image until next year". Wang, a strongly-touted candidate for the politburo when the Hu / Wen generation retires, had been projecting a "Happy Guangdong" model of development to level the wealth gap and emphasise social harmony. Police only returned on the fourth day after the riots.[18]

Land grab and resolution

Addressing the land dispute underlying the unrest, a senior official admitted that a sale of the land was planned, and interested property developers had already surveyed the site with local officials, but officials said that no contract had yet been signed.[9] Guangdong media published reports that suggested protesters acted as mobs that assaulted and injured dozens of riot policemen. Villagers accused the press of blatant bias.[9]

The Shanwei city government offered to appoint an inter-agency committee to delve into the land seizure allegations in exchange for an immediate end to the protests.[31] Officials also said they would consider a fresh village election for clean and fair representatives to take part in future land negotiations. Because the government had agreed to deal with the issue openly and fairly, the villagers temporarily suspended their protests.[18]

December uprising

The local government agreed to negotiate with thirteen democratically elected officials from Wukan; but, before the negotiations could settle any of the villagers' disputes, three of the representatives were arrested. One of the representatives, Xue Jinbo (薛錦波) died in police custody under mysterious circumstances.[21] After news of Xue's death became widely known, the villagers forcefully evicted local Communist Party officials and police from the village, leading to a blockade of the village by police.[6]

Death of Xue Jinbo

Xue Jinbo was arrested by plainclothes police without a warrant in front of a restaurant just before noon (local time) on 9 December 2011. He was taken away in a minibus without licence plates.[3] Four other village representatives were also detained on 9 December 2011.

At 11 pm in the evening of 11 December, a Lufeng City official, Huang, called Xue's daughter asking about Xue's full medical history, stating that Xue had been admitted to hospital in critical condition.[3] Xue's daughter and wife went to the hospital at Shanwei in the following few hours, and were made to wait without having access to Xue. Officials told the Xue family that Xue Jinbo had arrived at a local prison at 7 am on 10 December and died at 10 am on 11 December. Other family members were contacted and arrived in Shanwei. Ten family members, including Xue's daughter and wife, were permitted to see Xue's body, but were prevented by police from using cameras and telephones.

The local police alleged that Xue had died suddenly of a heart attack after he had confessed to damaging property and disrupting public services, but his friends and family rejected this explanation, and believed that Xue had died after being subjected to police brutality.[21] According to Xue's relatives, Xue's body showed signs of torture:[32] it was covered in bruises and cuts, both his nostrils were caked with blood, his thumbs were bent and twisted backwards. His daughter said her father had "a large bruise on his back suggested he had been kicked from behind."[3] Xue's son-in-law Gao also noted that Xue's knees were bruised. Because Xue's clothes were clean, his family suggested that he had been stripped and then tortured.[10] Xue's family refused official requests for an autopsy to be carried out.[33]

China News Service reported on 14 December that Xue's family members agreed with medical examiners' verdict that Xue died of "sudden cardiac failure".[25] Xinhua News stated that he had a history of asthma and heart disease that forensic investigators had found no evidence of abuse, and that Xue died of cardiac arrest at age 42 / 43.[10] Xue's eldest daughter, Xue Jianwan, categorically denied to a Hong Kong online journal, iSun Affairs, that her father had a history of heart problems.[4] Villagers held a two-hour vigil for him at his home.[34] Two post-mortem examinations were carried out: the first was undertaken by the Shanwei public security department, after which the family was informed that Xue had died of "sudden cardiac death". Following the family's protests, the authorities consented to a second autopsy, which was carried out by the medical examiner from Zhongshan University, Guangzhou. At no stage were any relatives present. The family said that the short written autopsy report given to them failed to address their queries.[35]

Uprising and siege

Villagers began holding daily protest meetings starting on 12 December.[5] Throughout mid-December the villagers protested against the local government, waiting for the intervention of the central government and hoping that the central government would conduct an investigation.[36][37]

After the news of Xue's death became widely known in Wukan on December 14, residents stormed the local police station and clashed with police, forcing them and local Communist Party officials out of the village.[6] After evacuating, the police cordoned off the area around the village and blocked the roads leading to it.[7] The government dispatched a force of 1000 armed officers to maintain order, but it was unsuccessful in retaking control of the village.[5] The authorities held the village in siege, preventing supplies from entering.[38]

Local Communist Party officials accused the Wukan village representatives of being ringleaders of the protests. County-level official Wu Zili accused village representatives Lin Zuluan and Yang Semao of organizing and inciting the villagers to set up barricades around the village since 8 December: "They did this to prevent officials from entering the village and to stop the perpetrators of the earlier riots from leaving the village and turning themselves into the authorities."[39]

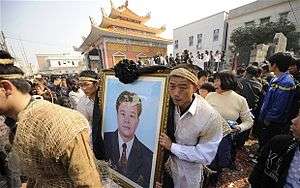

On 16 December, provincial Chinese officials "vowed to temporarily halt questionable property sales and to investigate claims that the local government illegally confiscated farmland for private development", according to official news media,[38] but he police refused to release the body of Xue Jinbo to his family in order to have it buried.[21] The same day, about 7000 people gathered for a ceremony for Xue Jinbo, and the standoff between villagers and authorities continued, with checkpoints from both sides set up around the village. Xue's son, Xue Jiandi, stated: "Right now we have only one demand, and that is that they return the body of my father, he belongs to us, not to the government."[40]

Protesters continued to demonstrate while displaying banners pledging loyalty to the Communist Party.[36] A villager reported that the government had offered rice and cooking oil – both of which were in low supply due to the blockade – to villagers who switch sides from the protesters and over to the government. The government gained at least a hundred supporters from the effort, but the stall was later shut down.[34]

On 18 December, Lin Zuluan, one of Wukan's representatives, said that "leaders at a higher level of local government summoned [him] for talks" and that they wished to go to the village. Lin Zuluan refused the proposal, saying that there could be no talks until Xue's body was released, the four other village representatives held by police were released, and the villagers' land was returned.[41] During the siege the villagers administered Wukan, as of 18 December 2011, from a temple to the goddess of the sea, Mazu.[41]

A breakthrough occurred on 20 December when senior provincial officials intervened in the dispute and acknowledged villagers' basic demands. The officials admitted to mistakes in handling the grievances and vowed to crack down on corruption.[42] On 21 December, after 3 tense days, the village representatives and government representatives reached a peaceful agreement for the villagers to stand down and cancel their march. In return, Xue's corpse would be released, and those detained by police would go free.[43][44] The provincial government also agreed to make the village's financial records public, to dismiss and investigate two local officials identified by villagers as responsible for the incident,[21] to address flaws in electing local officials, and to redistribute land which had been confiscated by the local government.[45]

News coverage

A survey conducted on 19 December by the Journalism and Media Studies Centre at the University of Hong Kong indicates strong coverage outside mainland China, but none of the 200+ newspapers inside the country published any articles. The story was extensively covered in Ming Pao and Apple Daily in Hong Kong; abroad, articles were published by the Financial Times, Reuters, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and others. 58 articles were surveyed across the region in total, of which 37 were from Hong Kong, 6 from Taiwan, 14 from Malaysia and 1 from Singapore.[46]

Some Sina Weibo microbloggers told the BBC that internet searches related to Wukan and the area were blocked after the December uprising started, and villagers' microblogs were deleted. Web users reacted by using alternative terms to refer to the events.[8]

In an undated video circulated to the national media, Zheng Yanxiong blamed the media for his woes in front of a group of local officials and village representatives, saying that cadres like him were the only ones facing increasing hardship every year: "Our powers decline every day, and fewer and fewer methods are at our disposal. But responsibility becomes bigger and bigger ... Ordinary people have bigger and bigger appetites, and become smarter every day. They are harder and harder to control." This attitude was lampooned in an opinion piece in The Standard.[47]

Xinhua and various state media, which had previously hardly reported the dispute, started publishing articles on 22 December that praised the provincial government for its handling of the event.[45] In a Global Times article, a public policy professor at Renmin University praised the provincial government's "evenhanded resolution" of the issue. He said: "The intervention is hard-earned progress, which rebutted previous claims by local authorities that the villagers had organized the protests 'out of malicious attempts'." Lin Zhe, professor at the Party School of the Party Central Committee, criticised local officials for having "poor sense of law and long-term neglect of the public's rights and interests," and said that the escalation of the dispute into violence would not have occurred if local authorities had "properly studied the complaints at the initial stages."[42]

International media commentary

During the protests, media including the BBC and the New York Times described the protests as "larger",[7] "unusual for their longevity",[10] and "a likely first in China's modern history".[6] The Wall Street Journal declared the protests "[2011's] most serious case of mass unrest in China".[11] However, after the protests' peaceful resolution, The Atlantic concluded that they were "not as unusual as it might have seemed" in the context of China's many small land and labor disputes, describing as "typical" the protestors' pledges of loyalty to the Communist Party of China.[48] Al Jazeera English has produced a four-part observational documentary series about Wukan's transition to democracy.[49]

2012 election

Following the standoff in December, protest leader Lin Zuluan was named the new Communist Party secretary of Wukan. As part of the truce with authorities, the governor of Guangdong, Wang Yang, acquiesced to a village election in Wukan: the first of its kind to employ a secret ballot.[50] A series of three elections was planned, which would select 100 representatives to oversee the village's governing committee.[50]

During the first round of elections on 1 February, some 6,000 Wukan villagers voted for an independent committee to supervise elections for a new village leadership.[51] On 11 February, over 6,500 villagers (85% of the population)[50] voted to elect 107 village representatives, with protester leader Lin Zuluan as village Party chief replacing the ousted leader, who had held the position for 42 years. The young Xue Jianwan, the daughter of the deceased protesters leader, Xue Jinbo, was also elected.[52] According to WSJ writer Josh Chin, the election appeared to be "free of the Communist Party meddling that typically mars Chinese election results."[53]

Impact

On similar village protests

Several other villages in China have drawn inspiration from the Wukan protests.

- In December 2011 residents of the nearby town of Haimen, Guangdong, staged large-scale protests over plans to expand a coal-fired power plant. The protests, which drew thousands of participants, were met with detentions and tear gassing by authorities.[54] Haimen residents told Reuters that they had followed developments in Wukan closely, regarding it as a good model of how citizens might negotiate with authorities.[55]

- On 17 January 2012 about 1,000 villagers from Baiyun district held a rally in front of Guangzhou city's government headquarters, angered by land seizures and corruption. The villagers threatened to turn the district into a "second Wukan" if their grievances were not resolved. Protesters said that Party secretary Li Zhihang had pocketed more than 400 million yuan and had embezzled up to 850,000 yuan from village operatives.[56]

- In February 2012 residents of East and West Panhe villages in Zhejiang staged protests against local officials over forced land requisitions with inadequate compensation. During a series of earlier protests in October 2011, police and government authorities reportedly fled the village.[57]

On Communist Party politics

Observers have credited the peaceful resolution of the Wukan protests to the intervention of the Communist Party chief in Guangdong, Wang Yang. By demonstrating his ability to resolve the issue peacefully, Wang has improved his reputation within the Party as a peacemaker who listens and responds to the interests of the people that he serves. Wang's improved reputation will make it more likely that he will be promoted to the powerful Politburo Standing Committee following the 18th Party Congress, later in 2012.[21]

The citizens of Wukan welcomed intervention by Wang's government, and Wang has capitalized on the popularity of his approach since late December 2011. In a meeting with the Guangdong Party congress in January 2012, Wang pledged to use his "Wukan approach" to improve village politics throughout the province. Wang, commenting on his resolution of the protests, has stated that it "was not only meant to solve problems in the village, but also to set a reference standard to reform village governance across Guangdong."[21]

People

- Xue Chang 薛昌 – CCP of Wukan, accused by villagers of corruption.[39]

- Chen Shunyi 陈舜意 – CCP of Wukan, accused by villagers of corruption.[39]

- Xue Jinbo 薛锦波 – Wukan's villagers representative.[39] Arrested by unknown people on 10 December, delivered to police on 11 December, died 2 hours later.

- Lin Zulian 林祖恋 – Wukan's villagers representative, formerly known as Lin Zuluan (林祖銮).[58]

- Yang Semao 杨色茂 – Wukan's villagers representative.[39]

- Wu Zili 吴紫骊 – Shanwei's mayor.[39]

- Zheng Yanxiong 郑雁雄 – Shanwei municipal committee secretary (汕尾市委書記).

- Zhu Mingguo 朱明国 – Guangdong province deputy secretary, mediated between parties, helping to solve the situation.

See also

- Dongzhou protests – which occurred in 2005 some 25 km to the southwest of Wukan.

- 2011 Haimen protest – nearby anti-pollution protest

References

- 1 2 "Google Maps – see label for 烏坎村 / Wukan cun". 19 December 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jacob, Rahul; Zhou, Ping (23 September 2011). Wukan protests set to escalate after child’s death

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moore, Malcom (16 November 2011). "Wukan siege: the fallen villager". The Daily Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 Buckley, Chris; Ben Blanchard; Ron Popeski (16 November 2011). "Chinese village activist's death suspicious-daughter". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moore, Malcom (14 December 2011). "Rebel Chinese village of Wukan 'has food for ten days'". The Daily Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2999. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 Krishnan, Ananth (14 December 2011). "A unique protest in China". The Hindu (India). Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Bristow, Michael (14 December 2011). "China protest worsens in Guangdong after villager death". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- 1 2 "China protest in Guangdong's Wukan 'vanishes from web'". BBC News. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Choi, Chi-yuk (7 October 2011) "Rioting in model village attests to graft woes". South China Morning Post

- 1 2 3 4 Jacobs, Andrew (14 December 2011). "Chinese Village Locked in Rebellion Against Authorities". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- 1 2 Page, Jeremy; Spegele, Brian (16 December 2011). "Beijing Set to 'Strike Hard' at Revolt", The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011

- ↑ Forsythe, Michael (6 March 2011). "China's Spending on Internal Police Force in 2010 Outstrips Defense Budget". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ↑ "Chinese village protester says government relents". CNN. 21 December 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "BBC News – China round-up: Friendship with North Korea stressed". BBC. 21 December 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Google Maps

- ↑ Google Maps; Guangdong Provincial Atlas.

- 1 2 Wines, Michael (25 December 2011). "A Village in Revolt Could Be a Harbinger for China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pomfret, James (29 September 2011). "Velvet glove trumps iron fist in south China land riot". Reuters. Retrieved 13 October 2011

- ↑ Rahul Jacob, Drop in China's land sales poses threat to growth, Financial Times, 7 December 2011.

- ↑ Simon Rabinovitch, Worries grow as China land sales slump, Financial Times, 5 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ewing, Kent. "Guangdong Boss Bets on Velvet Glove". Asia Times Online. January 7, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2012

- ↑ Elizabeth C. Economy, A Land Grab Epidemic: China’s Wonderful World of Wukans, Council on Foreign Relations, 7 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chinese villagers riot over govt land seizure". Gulf Times. AFP. 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Demick, Barbara (10 October 2011) "Protests in China over local grievances surge, and get a hearing". Los Angeles Times / Sacramento Bee

- 1 2 Mattis, Peter (20 December 2011). "Wukan Uprising Highlights Dilemmas of Preserving Stability. China Brief Volume 11, Issue 23. Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012

- ↑ "Protesters riot in China city over land sale". BBC News. 23 September 2011.

- ↑ Lau, Mimi (20 December 2011). "Villagers vow to fight if police attack". South China Morning Post

- 1 2 3 Wong, Gillian (23 September 2011) "Villagers riot in southern China over land dispute". Associated Press

- ↑ Jacobs, Andrew (25 September 2011). "Wave of riots over China land grabs". The Age (Australia).

- ↑ Jacobs, Andrew (23 September 2011). "Farmers in China’s South Riot Over Seizure of Land". The New York Times.

- ↑ "China vows probe to defuse violent land protest". Associated Press, Forbes. 25 September 2011

- ↑ Jacobs, Andrew (14 December 2011) "Village Revolts Over Inequities of Chinese Life". The New York Times Archived from the original on 23 December 2011

- ↑ "Guangdong Villagers Win Concessions". Radio Free Asia. 12 December 2011.

- 1 2 Moore, Malcolm (16 December 2011). "Wukan siege: rebel Chinese village holds memorial for fallen villager". Telegraph. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ↑ "官方驗屍不可信" ["Official autopsy 'unreliable']". Ming Pao 12 June 2012. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012

- 1 2 Moore, Malcolm (15 December 2011). "Wukan siege: First crack in the villagers' resolve". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011.

- ↑ "陸豐示威籲中央介入". Sing Pao. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011

- 1 2 Jacobs, Andrew (16 December 2011). "Provincial Chinese Officials Seek to End Village Revolt". New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Moore, Malcolm (15 December 2011). "Wukan siege: Chinese government vows to hunt down rebel village 'leaders'". Daily Telegraph, 15 December 2011

- ↑ "China village protest: Wukan mediator Xue Jinbo mourned". BBC News. 16 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- 1 2 Simpson, Peter (18 December 2011). "Wukan siege: rebel Chinese villagers reject resolution talks". The Daily Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- 1 2 Huang Jingjin (23 December 2011). "Investigation in Wukan". Global Times Archived from the original on 23 December 2011

- ↑ 中國廣東陸豐市烏坎村抗議事件21日新進展: 達成共識(圖),中國財經日報,2011年12月21日

- ↑ Sven Hansen. "Fischerdorf besiegt die KP". Taz.de. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 "China’s State-Run Newspapers Praise Government Handling of Wukan Protests". Bloomberg News. 22 December 2011. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011

- ↑ David Bandurski (19 December 2011). "Chinese-language coverage of Wukan". Journalism and Media Studies Centre (University of Hong Kong) Archived from the original on 22 December 2011

- ↑ "Talk is cheap at local level". 23 December 2011. The Standard.

- ↑ Fisher, Max (5 January 2012). "How China Stays Stable Despite 500 Protests Every Day". The Atlantic. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ↑ "Wukan: After the Uprising". Al Jazeera English. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Rahul Jacob and Zhou Ping, Wukan’s young activists embrace new role, Financial Times, 12 February 2012.

- ↑ "Southern China Protest Village Begins Choosing New Leaders". 2 February 2012. Businessweek Archived from the original on 2 February 2012

- ↑ (Bangkok Post) (article to read and integrate)

- ↑ Chin, Josh (1 February 2012). Wukan Elections the Spark to Set the Prairie Ablaze? Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Michael Wines, Police Fire Tear Gas at Protesters in Chinese City, New York Times, 23 December 2011.

- ↑ Reuters, Chinese official denies reports of deaths at Haimen protest, 21 December 2011.

- ↑ South China morning post. Guangzhou land rally erupts amid key meeting. 18 January 2012.

- ↑ China Digital Times, Wukan 2.0? Zhejiang Villagers Protest Land Grabs, 8 February 2012.

- ↑

External links

- Wukan siege in pictures, Daily Telegraph.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||