Fasciola hepatica

| Fasciola hepatica | |

|---|---|

| | |

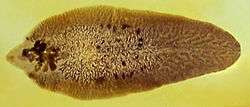

| Fasciola hepatica – adult worm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Trematoda |

| Subclass: | Digenea |

| Order: | Echinostomida |

| Suborder: | Distomata |

| Family: | Fasciolidae |

| Genus: | Fasciola |

| Species: | F. hepatica |

| Binomial name | |

| Fasciola hepatica Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Fasciola hepatica, also known as the common liver fluke or sheep liver fluke, is a parasitic trematode (fluke or flatworm, a type of helminth) of the class Trematoda, phylum Platyhelminthes that infects the livers of various mammals, including humans. The disease caused by the fluke is called fascioliasis or fasciolosis, which is a type of helminthiasis and has been classified as a neglected tropical disease.[1] F. hepatica is distributed worldwide, has been known as an important parasite of sheep and cattle for hundreds of years and causes great economic losses in sheep and cattle. Because of its size and economic importance, it has been the subject of many scientific investigations and may be the best-known of any trematode species.

Morphology

Fasciola hepatica is one of the largest flukes of the world, reaching a length of 30 mm and a width of 13 mm. It is leaf-shape, pointed at the end or posteriorly, and wide in the front or anteriorly, although the shape varies somewhat. The oral sucker is small but powerful and is located at the end of a cone-shape projection at the anterior end. The acetabulum is larger than the oral sucker and is anterior. The internal tegument is covered with large, and scalelike spines. The intestinal ceca are highly dendritic and extend to near the posterior end of the body. The testes are large and greatly branched, arranged in tandem behind the ovary. The smaller, dendritic ovary lies on the right side, coiling between the ovary and the preacetabular cirrus pouch. Vitelline follicles are extensive, filling most of the lateral body and becoming confluent behind the testes.

Body Wall

The body wall consists of the cuticle, basement membrane, musculature and parenchyma cells.

Cuticle

It is surface resist layer which protect fluke from digestive juice of host.

Basement Membrane

Below the cuticle lies basement membrane. It create a boundary between cuticle and musculature.

Musculature

The musculature consists of up to three muscle layers:

- Outer-Circular muscle

- Middle-Longitudinal muscle

- Inner-Diagonal muscle

Parenchyma cell

Below the musculature lies the parenchyma cells, which bear numerous uni-nucleated cells surrounded by fluid-filled spaces.

Life cycle

To complete its life cycle, F. hepatica requires a freshwater snail as an intermediate host, such as Galba truncatula, in which the parasite can reproduce asexually.

Species in the family of air-breathing freshwater snails, the Lymnaeidae that serve as naturally or experimentally intermediate hosts of Fasciola hepatica include: Austropeplea tomentosa, Austropeplea ollula, Austropeplea viridis, Radix peregra, Radix lagotis, Radix auricularia, Radix natalensis, Radix rubiginosa, Omphiscola glabra, Lymnaea stagnalis, Stagnicola fuscus, Stagnicola palustris, Stagnicola turricula, Pseudosuccinea columella, Lymnaea viatrix, Lymnaea neotropica, Fossaria bulimoides, Lymnaea cubensis, Lymnaea sp. from Colombia, Galba truncatula, Lymnaea cousini, Lymnaea humilis, Lymnaea diaphana, Stagnicola caperata, and Lymnaea occulta.[2]

The metacercariae are ingested by the ruminant or, in some cases, by humans eating uncooked foods such as watercress or salad. Contact with low pH in the stomach causes the early immature juvenile to excyst. In the duodenum, the parasite breaks free of the metacercariae and burrows through the intestinal lining into the peritoneal cavity. The newly excysted juvenile does not feed at this stage, but, once it finds the liver parenchyma after a period of days, feeding will start. This immature stage in the liver tissue is the pathogenic stage, causing anaemia and clinical signs sometimes observed in infected animals or humans. The parasite browses on liver tissue, on the lining of biliary ducts, for a period of up to six weeks, and eventually finds its way to the large bile duct, where it matures into an adult. Adult hepatica lives in small passages of the liver of many kinds of mammals, especially ruminants and begins to produce eggs. Up to 25,000 eggs per day per fluke can be produced, and, in a light infection, up to 500,000 eggs per day can be deposited onto pasture by a single sheep.

Eggs are passed out of the liver with bile and into the intestine to be voided with feces. If they fall into water, eggs will complete their development into miracidia and hatch in 9 to 10 days during warm weather. Colder water retards their development. On hatching, miracidia have 24 hours in which they have to find a suitable snail host. Mother sporocysts produce first-generation rediae, which in turn produce daughter rediae that develop in the snail's digestive gland. From the snail, minute cercariae emerge and swim through pools of water in pasture, and encyst as metacercariae on near-by vegetation.

Epidemiology

Infection begins when metacercaria - infected aquatic vegetation is eaten or when water containing metacercariae is drunk. In the United Kingdom, fasciola frequently causes disease in ruminants, most commonly between March and December.[3]

Humans are often infected by eating watercress or drinking 'Emoliente', a Peruvian drink that uses drops of watercress juice.[3] Cattle and sheep are infected when they consume the infectious stage of the parasite from low-lying, marshy pasture.

Human infections occur in parts of Europe, like England and Ireland, Northern Iran, northern Africa, like Egypt, in Cuba, South America, especially the Altiplano regions of the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes and are emerging in Vietnam and Cambodia. As of 2014, the prevalence in children between 3 and 12 years was 11% by stool microscopy and ELISA in the cattle farming areas near Cusco, Peru. Risk factors were number of siblings in the household, drinking untreated water, and giardiasis.[4]

It is one of the most important disease agents of domestic stock throughout the world and likely will remain so in the future.

The presence of Fasciola hepatica confounds the detection of bovine tuberculosis in cattle. Cattle co-infected with F. hepatica, compared to those infected with M. bovis alone, react less strongly to the single intradermal comparative cervical tuberculin (SICCT) test.[5]

Diagnosis

A diagnosis may be made by finding yellow-brown eggs in the stool. They are indistinguishable from the eggs of Fascioloides magna, although the eggs of F. magna are very rarely passed in sheep, goats, or cattle. A false record can result when the patient has eaten infected liver and egg passes through the feces. Daily examination during a liver-free diet will unmask the false diagnosis.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test is the test of choice. The ELISA is available commercially and can detect anti-hepatica antibodies in serum and milk; new ones especially intended for use on fecal samples are being developed. ELISA is more specific than Western blot or Arc2 immunodiffusion.[3]Proteases secreted by F. hepatica have been used experimentally in immunizing antigens.

See also

References

- ↑ "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. June 6, 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ↑ Correa, C. A.; Escobar, J. S.; Durand, P.; Renaud, F.; David, P.; Jarne, P.; Pointier, J.-P.; Hurtrez-Boussès, S. (2010). "Bridging gaps in the molecular phylogeny of the Lymnaeidae (Gastropoda: Pulmonata), vectors of Fascioliasis". BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 381. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-381. PMC 3013105. PMID 21143890.

- 1 2 3 "Gorgas Case 5 - 2015 Series". The Gorgas Course in Clinical Tropical Medicine. University of Alabama. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Cabada, MM; Goodrich, MR; Graham, B; Villanueva-Meyer, PG; Lopez, M; Arque, E; White, AC Jr (Nov 2014). "Fascioliasis and eosinophilia in the highlands of Cuzco, Peru and their association with water and socioeconomic factors". Am J Trop Med Hyg 91 (5): 989–93. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.14-0169. PMC 4228897. PMID 25200257.

- ↑ Claridge, Jen; Diggle, Peter; McCann, Catherine M.; Mulcahy, Grace; Flynn, Rob; McNair, Jim; Strain, Sam; Welsh, Michael; Baylis, Matthew; Williams, Diana J.L. (2012). "Fasciola hepatica is associated with the failure to detect bovine tuberculosis in dairy cattle". Nature Communications 3: 853. doi:10.1038/ncomms1840. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

External links

- Animal Diversity Web University of Michigan

- Parasites in humans

- Parasite Parasite .org Australia

- Stanford University

- Taxonomic classification

- Encyclopedia of Life

- Taxonomy and nomenclature at ITIS.gov

- Molecular database at UniProt

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fasciola hepatica. |