Dermatomyositis

| Dermatomyositis | |

|---|---|

Gottron's papules. Discrete erythematous papules overlying the metacarpal and interphalangeal joints in a person with juvenile dermatomyositis. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| ICD-10 | M33.0-M33.1 (ILDS M33.910) |

| ICD-9-CM | 710.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 10343 |

| MedlinePlus | 000839 |

| eMedicine | med/2608 derm/98 |

| MeSH | D003882 |

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a connective-tissue disease related to polymyositis (PM) that is characterized by inflammation of the muscles and the skin. While DM most frequently affects the skin and muscles, it is a systemic disorder that may also affect the joints, the esophagus, the lungs, and the heart.[1] In the United States, the incidence of DM is estimated at 5.5 cases per million people.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptoms include skin rash and symmetric proximal muscle weakness (in over 90% of patients[3]) which may be accompanied by pain. The pain may resemble the type experienced after strenuous exercise. Some dermatomyositis patients have little pain, while in others (esp. in juvenile dermatomyositis), the pain may be severe. It is important to remember that this condition varies from person to person in many ways. Also in many cases muscle may deteriorate and render the patient temporarily paralyzed unable to walk, run, get out of bed, or even swallow food and liquids.

Skin findings occur in dermatomyositis but not PM and are generally present at diagnosis. Gottron's sign is an erythematous, scaly eruption occurring in symmetric fashion over the MCP and interphalangeal joints (can mimic psoriasis). The heliotrope or "lilac" rash[4] is a violaceous eruption on the upper eyelids and in rare cases on the lower eyelids as well, often with itching and swelling (most specific, though uncommon). Shawl (or V-) sign is a diffuse, flat, erythematous lesion over the back and shoulders or in a "V" over the posterior neck and back or neck and upper chest, which worsens with UV light. Erythroderma is a flat, erythematous lesion similar to the shawl sign but located in other areas, such as the malar region and the forehead. Periungual telangiectasias and erythema occur.

"Mechanic's hands" (also in PM) refers to rough, cracked skin at the tips and lateral aspects of the fingers forming irregular dirty-appearing lines that resemble those seen in a laborer (this is also associated with the anti-synthetase syndrome). See: sclerodactyly. Psoriaform changes in the scalp can occur. Centripetal flagellate erythema comprises linear, violaceous streaks on the trunk (possibly caused by itching pruritic skin). Calcinosis cutis (deposition of calcium in the skin) is usually seen in juvenile dermatomyositis, not adult dermatomyositis. Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) is another feature, occurring in as many as 33% of cases.

Dermatomyositis occurs more commonly in female patients. The initial symptoms may vary considerably, from dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), feverish sensations, and most often proximal symmetrical muscle weakness with vasculitis affecting the skin, muscles and internal organs. Patients find it hard to raise their arms to comb their hair or walk up the stairs due to the proximal muscle weakness. It can be severe enough to affect the muscles needed for speech and/or swallowing and is also known to cause respiratory compromise (due to a variety of mechanisms). Calcinosis can occur in the skin, joints and tissues. ESR and CPK tend to be elevated, along with typical EMG findings of spontaneous muscle fibrillation and short polyphasic muscle potentials. However, the findings may be variable if the disease affects only patches of muscle and/or overlaps with an autoimmune disease. Definitive diagnosis is through muscle biopsy, which may isolate the type of disease and severity of involvement.

When present, Gottron's papules — scaly erythematous eruptions or red patches overlying the knuckles, elbows, and knees — are characteristic of dermatomyositis, though not seen in every patient. Other skin manifestations involve periungual telangiectasias and a heliotrope (purple) rash over the upper eyelids. The rash over the upper eyelids may be the only sign of skin involvement in some cases.

-

Gottron's papules. Erythematous to violaceous raised papules overlying the metacarpal and interphalangeal joints in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis.

-

Gottron's papules. Characteristic raised erythematous papule overlying the proximal interphalangeal joint in a patient with dermatomyositis.

-

Gottron's papules. Erythematous plaques overlying the elbows in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis. In some patients, small erythematous plaques may overly the extensor aspects of larger joints, such as the elbows, knees, and medial malleoli. This is considered to be an extended part of the spectrum of Gottron's papules.

-

Gottron's papules. Erythematous plaques overlying the elbows in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis. In some patients, small erythematous plaques may overly the extensor aspects of larger joints, such as the elbows, knees, and medial malleoli. This is considered to be an extended part of the spectrum of Gottron's papules. Note in Figure, a focal area of dystrophic calcification at the site of Gottron's papules, which is indicative of damage, as discussed below.

-

Gottron's papules with telangiectasia. Gottron's papules with prominent atrophy, porcelain white scarring, and telangiectasia.

-

Gottron's sign. Confluent macular erythema with scale confined to the skin overlying the patellae in a girl with juvenile dermatomyositis.

-

Gottron's papules showing secondary atrophy and telangiectasia in a girl with severe juvenile dermatomyositis. These changes are seen in association with prominent periungual erythema, a cutaneous finding indicative of ongoing disease activity.

-

Heliotrope. Confluent macular erythema confined to the upper eyelid, with associated periorbital edema.

-

Heliotrope. In patients who have darker skin types (type III - VI skin), heliotrope can be subtle and perceived as inactive or normal, resulting in under-diagnosis in this presenting sign of dermatomyositis.

-

Heliotrope is often associated with periorbital edema and telangiectasias of the upper eyelids. In the resolution stage, atrophy or dyspigmentation (hypo- or hyperpigmentation) may be apparent. Heliotrope. Subtle erythema and minimal edema involving both upper eyelids, with extension to the lower eyelids.

-

Malar and facial erythema. Acute onset of confluent macular erythema in a periorbital and malar distribution with extension to the chin in a girl with juvenile dermatomyositis. Note the perioral sparing.

-

Malar and facial erythema. Striking malar and facial erythema with facial edema and scale represents a recent disease flare in an adult patient with dermatomyositis.

-

Linear extensor erythema. Confluent erythema of the skin overlying the interphalangeal and extensor tendons of the hand, with extension to the forearm in a patient with dermatomyositis

-

Linear extensor erythema involving the forearm. This image demonstrates linear violaceous discrete and confluent macules, and erosions secondary to excoriation. Pruritus is an under-recognized symptom of active dermatomyositis.

Causes

The cause is unknown, but it may result from an initial viral or bacterial infection (even after treatment or cure of the infection). In cases that follow closely after pregnancy, some research suggests an immune response to lingering fetal cells still circulating in the mother becoming an immune response against the parent, resulting in chronic autoimmune activity. Regardless of the trigger, dermatomyositis may behave as a systemic autoimmune disease. Many people diagnosed with dermatomyositis were previously diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus, Chlamydia pneumoniae, psittacosis, and other types of infections. Some cases of dermatomyositis actually "overlap" (i.e. co-exist with or are part of a spectrum that includes) other autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren's syndrome, lupus, scleroderma, or vasculitis. Because of the link between dermatomyositis and autoimmune disease, doctors and patients suspecting dermatomyositis may find it helpful to run an ANA - antinuclear antibody - test, which in cases of a lupus-like nature may be positive (usually from 1:160 to 1:640, with normal ranges at 1:40 or 1:80 and below).

Though several cases of "myositis" were reported as being triggered by the use of various statin drugs (used to control blood cholesterol), the behavior of muscle inflammation linked to statin drugs is different than either dermatomyositis or polymyositis (D.M./P.M.) Muscle biopsies of the statin patients showed rhabdomyolysis, with patterns of degeneration and regeneration of muscle tissue, whereas biopsies of dermatomyositis show "perivascular infiltrates of inflammatory cells,"and muscle regeneration is not present. However, a patient who already has either D.M. or P. M. may need expert advice before taking the risk of statin therapy, since a bout of muscle pain could then be attributed to either the statin or the underlying condition.

High blood levels of creatine kinase (CPK) are often, but not always present in dermatomyositis or polymyositis, causing some patients to be misdiagnosed. The "CPK" levels tend to rise when abnormal inflammation occurs to skeletal muscles and/or other areas of the body. However, since dermatomyositis is highly individualistic, the CPK may be helpful but should not be definitive as a tool for diagnosis. Obviously, extremely high levels on CPK (as seen in rhabdomyolysis) indicate heavy damage to these muscles and other internal organs, such as the kidneys.. Without treatment, kidney damage occurs and death in the more severe cases. Since dermatomyositis may still damage the heart, intestines, or breathing muscles in a "patchy" way, the definitive test is a muscle biopsy on the affected areas (usually the upper arms/ upper legs). Expertly done E.M.G. testing usually tracks "flagrant" D.M., though again, the neurologist should look for "patches" of involvement in unusual patients who seem to have "normal" tests after having other indications of D.M./P.M..

Many cases of dermatomyositis are a paraneoplastic phenomenon, indicating the presence of cancer.[5] In cases involving cancer (not only of the breast), if the cancer is pre-existent, removal of the cancer usually results in remission of the dermatomyositis. Because of a high cancer risk, both before and after diagnosis, Rheumatology experts will often run several cancer tests at the onset of dermatomyosits/polymyosits. Cancer will continue to be a risk with such patients, and some cancer screening should be continued, particularly because of the high-risk immune-suppressing treatments used in more severe cases. Though rash appearing on a patient with "polymyositis" may cause concern, it should be remembered that photo-sensitive rashes may be linked to both conditions as in lupus (i.e., the two disorders cannot always be easily distinguished). Another sign of possible neoplastic change may include examination of the fingers. Inflamed cuticles with closed capillary loops and splitting at the finger-tips can indicate a very severe case of dermatomyosis—with all the cancer risks involved.

In his 1988 article, Clinical pathologic correlations of Lyme disease by stage, noted Lyme disease researcher Alan Steere observed, "[...] the perivascular lymphoid infiltrate in clinical myositis does not differ from that seen in polymyositis or dermatomyositis. All of these histologic derangements suggest immunologic damage in response to persistence of the spirochete, however few in number."[6]

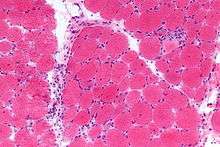

Pathophysiology

The mechanism is conjectured to be complement-mediated damage of microscopic vessels with muscle atrophy and lymphocytic inflammation secondary to tissue ischemia.[7]

Microscopic findings

Cross sections of muscle reveal muscle fascicles with small, shrunken polygonal muscle fibers on the periphery of a fascicle surrounding central muscle fibers of normal, uniform size.

Aggregates of mature lymphocytes with small, dark nuclei and scant cytoplasm are seen surrounding vessels. Other inflammatory cells are distinctly uncommon. Immunohistochemistry can be used to demonstrate that both B- and T-cells are present in approximately equal numbers.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of dermatomyositis can be confirmed by muscle biopsy, skin biopsy, EMG,and blood tests. It should be noted, however, that only muscle biopsy is truly diagnostic; liver enzymes and EMG are relatively non-specific. Other enzymes, specifically creatine phosphokinase (CPK), are the major tool in assessing the progress of the disease and/or the efficacy of treatment. On the muscle biopsy, there are two classic microscopic findings of dermatomyositis. They are:

- A mixed B- and T-cell perivascular inflammatory infiltrate

- Perifascicular muscle fiber atrophy

And on the skin biopsy: Histopathology of skin biopsies from patients with dermatomyositis shows perivascular inflammation, hyperkeratosis in the stratum corneum, epidermal atrophy, follicular plugging, and interface dermatitis (inflammatory cells at or obscuring the dermalepidermal junction). These changes are not specific for dermatomyositis because they can also be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus.[8]

Dermatomyositis is associated with autoantibodies, especially anti-Mi-2 antibodies, and to a lesser extent anti-Jo-1 antibodies, which are more commonly seen in polymyositis.

X-ray findings sometimes include dystrophic calcification in the muscles, and person may or may not notice small calcium deposits under the skin. Many do not have any calcium deposits of any kind. The rash also may come and go, and may not be dependent on the severity of the muscle involvement at the time.

Classification

Dermatomyositis is considered a muscular dystrophy by the Muscular Dystrophy Association.[9] It is also a type of autoimmune connective tissue disease.[10] It is related to polymyositis and inclusion body myositis.

There is a form of this disorder that strikes children, known as juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM).

Differential diagnosis

Dermatomyositis must be differentiated from other common, lymphocyte predominant inflammatory myopathies. If present, the characteristic perifascicular atrophy makes this distinction trivial.

There is some overlap in the microscopic appearances of different inflammatory myopathies, but some helpful differences are often present.[11] The rimmed vacuoles of inclusion body myositis (IBM) are absent in dermatomyositis. Polymyositis is characterised by diffuse or patchy inflammation of the muscle fascicles, a random pattern of muscle atrophy, and T-cell predominance with T-cells seen invading otherwise viable appearing muscle fibers. Dermatomyositis has been associated with cases of Lyme Disease.[12]

Treatment

This can be treated with steroids and a mild dose of chemotherapy. Specialized exercise therapy may supplement treatment to enhance quality of life.

Medications to help relieve symptoms include:

- Prednisolone

- Methotrexate

- Mycophenolate

- Hydroxychloroquine

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- Low-dose naltrexone

- Intravenous immunoglobulin

- Azathioprine

- Cyclophosphamide

- Tacrolimus

- Infliximab

- Rituximab[13]

Prognosis

Before the advent of modern treatments such as prednisone, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, chemotherapies, and other drugs, the prognosis was poor.[14] Now there are numerous treatments and immunomodulatory drugs. According to published data in 2012 (based on a study of random adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis patients seen at the University of Michigan from 1997 to 2003) the survival rates for dermatomyositis were 70% at 5 years and 57% at 10 years.[15] Thus, it is important that treatment begin as soon as possible. The cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis may or may not improve with therapy in parallel with the improvement of the myositis. In some patients the weakness and rash resolve together. In others, the two are not linked, with one or the other being more challenging to control. Often, cutaneous disease persists after adequate control of the muscle disease.[8]

Notable cases

- The opera singer Maria Callas (1923 - 1977) suffered from dermatomyositis from 1975 until her death.[16][17]

- The actor Laurence Olivier (1907 – 1989) suffered from dermatomyositis from 1974 until his death.[18]

- The American football running back Ricky Bell (1955 - 1984), the runner-up for the Heisman Trophy in 1976, and the number-one choice in the NFL draft in 1977, died at the age of 29 from heart failure caused by this disease.[19]

- Rob Buckman (1948 - 2011) a doctor, comedian, author, and the president of the Humanist Association of Canada.[20][21]

See also

References

- ↑ Jeffrey P Callen (12 October 2011). "Dermatomyositis". Medscape reference. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ http://www.bio.davidson.edu/courses/immunology/students/spring2003/statler/dermatomyositis.htm.

- ↑ Bohan A, Peter JB, Bowman RL, Pearson CM. Computer-assisted analysis of 153 patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(4):255.

- ↑ Page 151 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.

- ↑ Scheinfeld NS (2006). "Ulcerative paraneoplastic dermatomyositis secondary to metastatic breast cancer". Skinmed 5 (2): 94–6. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2006.03637.x. PMID 16603844.

- ↑ Duray PH, Steere AC, "Clinical pathologic correlations of Lyme disease by stage."

- ↑ Benveniste, O; Squier W; Boyer O; et al. (November 2004). "Pathogenesis of primary inflammatory myopathies". Presse Médicale 33 (20): 1444–1450. doi:10.1016/S0755-4982(04)98952-X. PMID 15611679.

- 1 2 http://www.myositis.org/storage/documents/Publications_for_website/2014_-_Myositis_101_ForDocs_small.pdf

- ↑ "Dermatomyositis".

- ↑ "Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis: Autoimmune Disorders of Connective Tissue: Merck Manual Home Edition".

- ↑ Nirmalananthan, N; Holton JL; Hanna MG (November 2004). "Is it really myositis? A consideration of the differential diagnosis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology 16 (6): 684–691. doi:10.1097/01.bor.0000143441.27065.bc. PMID 15577605.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Dermatomyositis+lyme

- ↑ Scheinfeld N (2006). "A review of rituximab in cutaneous medicine". Dermatol. Online J. 12 (1): 3. PMID 16638371.

- ↑ Page 285 in: Thomson and Cotton Lecture Notes in Pathology, Blackwell Scientific. Third Edition

- ↑ http://arthritis-research.com/content/14/1/R22

- ↑ Maria Callas#Fussi and Paolillo report

- ↑ "Greek Reporter: 'Maria Callas did not kill herself from grief for Onassis, a rare disease cost her career and life'". GR Reporter. 28 December 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "Laurence Olivier Dies: 'The Rest Is Silence'". People Magazine. 24 July 1989. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ↑ "Forgotten: Ricky Bell". Pro Football Weekly. 8 January 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ↑ "Rob Buckman obituary". The Guardian Newspaper. 12 October 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ↑ "Dr. Robert Buckman, renowned oncologist, comedian and Star columnist, dead at 63". The Toronto Star Newspaper. 10 October 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

External links

- The American College of Rheumatology's patient education page on myopathy

- Illustration of Gottron's papules at University of Iowa

- The Johns Hopkins Myositis Center

- Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis, Merck Manual (Professional Version)

- Dourmishev, Lyubomir A.; Dourmishev, Assen Lyubenov (2009). Dermatomyositis: Advances in Recognition, Understanding and Management (2009 ed.). Germany: Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3642098185.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|