Shapur II

| Shapur II 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 | |

|---|---|

| "King of kings of Iran and Aniran" | |

Bust of Shapur II | |

| Reign | 309–379 |

| Predecessor | Adur Narseh |

| Successor | Ardashir II |

| Born |

309 Possibly Gor, Pars |

| Died |

379 (aged 70) Bishapur, Pars |

| Consort | Sithil-Horak |

| Issue |

Shapur III Zurvandukht |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Hormizd II |

| Mother | Ifra Hormizd |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

| ||||||

Shapur II (Middle Persian: 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 Šāhpuhr), also known as Shapur II the Great (Persian: شاپور دوم بزرگ), was the tenth king of the Sasanian Empire. The longest reigning Sasanian monarch, he reigned from 309 to 379. He was the son of Hormizd II (r. 302–309). During Shapur II's long reign, the Sasanian Empire saw its first golden era.

Accession

When Hormizd II died in 309, he was succeeded by his son Adur Narseh, who, after a brief reign which lasted few months, was killed by some of the nobles of the empire.[1] They then blinded the second,[2] and imprisoned the third (Hormizd, who afterwards escaped to the Roman Empire).[3] The throne was reserved for the unborn child of Hormizd II's wife Ifra Hormizd, which was Shapur II. It is said that Shapur II may have been the only king in history to be crowned in utero, as the legend claims that the crown was placed upon his mother's womb while she was pregnant.[4]

However, according to Shapur Shahbazi, it is unlikely that Shapur was crowned as king while still in his mother's womb, since the nobles could not have known of his sex at that time. He further states that Shapur was born 14 days after his father's death, and that the nobles killed Adur Narseh and crowned Shapur II in order to gain greater control of the empire, which they were able to do until Shapur II reached his majority at the age of 16.[5][2]

Reign

War with the Arabs

During the childhood of Shapur II, Arab nomads made several incursions into the Sasanian homeland of Pars, where they raided Gor and its surroundings.[5] Furthermore, they also made incursions into Meshan and Mazun. At the age of 16, Shapur II led an expedition against the Arabs; primarily campaigning against the Ayad tribe in Asoristan and thereafter he crossed the Persian Gulf, reaching al-Khatt, a region between present-day Bahrain and Qatar. He then attacked the Banu Tamim in Hajar mountains. Shapur II reportedly killed a large number of the Arab population and destroyed their water supplies by stopping their wells with sand.[6]

After having dealt with the Arabs of eastern Arabia, he continued his expedition into western Arabia and Syria, where he attacked several cities—he even went as far as Medina.[7] Because of his cruel way of dealing with the Arabs, he was called Dhū al-aktāf ("he who pierces shoulders") by them.[5][4] Not only did Shapur II pacify the Arabs of the Persian Gulf, but he also pushed many Arab tribes further deep into the Arabian Peninsula. Furthermore, he also deported some Arab tribes by force; the Taghlib to Bahrain and al-Khatt; the 'Abd al-Qays and Banu Tamim to Hajar; the Banu Bakr to Kirman, and the Banu Hanzalah to a place near Hormizd-Ardashir.[5] Shapur II, in order to prevent the Arabs to make more raids into his country, ordered the construction of a wall near al-Hira, which became known as war-i tāzigān ("wall of the Arabs").

The Zoroastrian scripture Bundahishn also mentions the Arabian campaign of Shapur II, where it says the following: "During the rulership of Shapur (II), the son of Hormizd, the Arabs came; they took Khorig Rūdbār; for many years with contempt (they) rushed until Shapur came to rulership; he destroyed the Arabs and took the land and destroyed many Arab rulers and pulled out many number of shoulders".[5]

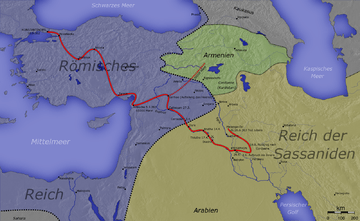

Early campaigns and first war against the Romans

In 337, just before the death of Constantine I (324–337), Shapur II, provoked by the Roman rulers' backing of Armenia,[8] broke the peace concluded in 297 between Narseh (293–302) and Emperor Diocletian (284–305), which had been observed for forty years. This was the beginning of two long drawn-out wars (337–350 and 358-363) which were inadequately recorded. After crushing a rebellion in the south, Shapur II invaded Roman Mesopotamia and recaptured Armenia. Apparently 9 major battles were fought. The most renowned was the inconclusive Battle of Singara (Sinjar, in Iraq) in which the Roman emperor Constantius II was at first successful, capturing the Persian camp, only to be driven out by a surprise night attack after Shapur had rallied his troops (344-or 348?). Gibbon asserts that Shapur II invariably defeated Constantius, but there is reason to believe that the honours were fairly evenly shared between the two capable commanders. (Since Singara was on the Persian side of the Mesopotamian frontier, this alone may suggest that the Romans had not seriously lost ground in the war up to that time.) The most notable feature of this war was the consistently successful defence of the Roman fortress of Nisibis in Mesopotamia. Shapur besieged the fortress three times[8] (337, 344? and 349) and was repulsed each time by Roman general Lucilianus.

Although often victorious in battles, Shapur II had made scarcely any progress. At the same time he was attacked in the east by Scythian Massagetae and other Central Asian tribes. He had to break off the war with the Romans and arrange a hasty truce in order to pay attention to the east (350). Roughly around this time the Hunnic tribes, most likely the Kidarites (Chinese Jiduolo), whose king was Grumbates, make an appearance as an encroaching threat upon Sasanian territory as well as a menace to the Gupta Empire (320-500CE).[8] After a prolonged struggle (353–358) they were forced to conclude a peace, and Grumbates agreed to enlist his light cavalrymen into the Persian army and accompany Shapur II in renewed war against the Romans.

Second war against the Romans and invasion of Armenia

In 358 Shapur II was ready for his second series of wars against Rome, which met with much more success. In 359, Shapur II invaded southern Armenia, but was held up by the valiant Roman defence of the fortress of Amida (Diyarbekir, in Turkey) which finally surrendered in 359 after a seventy-three day siege in which the Persian army suffered great losses. The delay forced Shapur to halt operations for the winter. Early the following spring he continued his operations against the Roman fortresses, capturing Singara and Bezabde (Cirze?). Constantius arrived from the west at this time, and unsuccessfully tried to recapture Bezabde.

In 363 the Emperor Julian (361–363), at the head of a strong army, advanced to Shapur's capital at Ctesiphon and defeated a superior Sasanian army at the Battle of Ctesiphon; however, he was killed during his retreat back to Roman territory. His successor Jovian (363–364) made an ignominious peace, by which the districts beyond the Tigris which had been acquired in 298 were given to the Persians along with Nisibis and Singara, and the Romans promised to interfere no more in Armenia. The great success is represented in the rock-sculptures near the town Bishapur in Persis (Stolze, Persepolis, p. 141); under the hooves of the king's horse lies the body of an enemy, probably Julian, and a supplicant Roman, the Emperor Jovian, asks for peace.

According to the peace treaty between Shapur and Jovian, Georgia and Armenia were to be ceded to Sasanian control, and the Romans forbidden from further involvement in the affairs of Armenia.[9] Under this agreement Shapur assumed control over Armenia and took its King Arsaces II (Arshak II), the faithful ally of the Romans, as prisoner, and held him in the Castle of Oblivion (Fortress of Andməš in Armenian or Castle of Anyuš in Ḵuzestān).[9] Supposedly, Arsaces then committed suicide during a visit by his eunuch Drastamat.[9] Shapur attempted to introduce Zoroastrian orthodoxy into Armenia. However, the Armenian nobles resisted him successfully, secretly supported by the Romans, who sent King Papas (Pap), the son of Arsaces II, into Armenia. The war with Rome threatened to break out again, but Valens sacrificed Pap, arranging for his assassination in Tarsus, where he had taken refuge (374). In Georgia where the Sasanians were also given control, Shapur II installed Aspacures II in eastern Georgia, however in western Georgia Valens also succeeded in setting up his own king Sauromaces II.[9] Shapur II subdued the Kushans and took control of the entire area now known as Afghanistan and Pakistan. Shapur II had conducted great hosts of captives from the Roman territory into his dominions, most of whom were settled in Susiana. Here he rebuilt Susa, after having killed the city's rebellious inhabitants.

Death and succession

Shapur later died in 379, although he had a son named Shapur III, he was succeeded by his brother Ardashir II. By Shapur's death the Sasanian Empire was stronger than ever before, considerably larger than when he came to the throne, the eastern and western enemies were pacified and Persia had gained control over Armenia. He is regarded as one of the most important Sassanian kings along with Shapur I and Khosrau I, and could after a long period of instability regain the old strength of the Empire. His three successors, however, were less successful than he. Furthermore, his death marked the start of a 125-year-long conflict between the Wuzurgan and the Sasanian kings who both struggled for power over Iran.[10]

Relations with the Christians

Shapur II was not initially hostile to his Christian subjects, who were led by Shemon Bar Sabbae, the Patriarch of the Church of the East. However, the conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine I to Christianity gave Shapur distrust towards his Christian subjects, whom he considered as agents of the foreign enemy. The war between the Sasanian and Roman empires changed Shapur's mistrust into hostility. After the death of Constantine, Shapur II, who had been preparing for war for several years, imposed a double tax on his Christian subjects in his empire to finance the conflict. Shemon, however, refused to pay double tax. Shapur then gave Shemon and his clergy a last chance to convert to Zoroastrianism, which they refused to do. It was during this period the "cycle of the martyrs" began during which "many thousands of Christians" were put to death. The two successors of Shemon, Shahdost and Barba'shmin, were also martyred the following years.

Imperial beliefs and numismatics

According to Ammianus Marcellinus, Shapur II fought the Romans in order to "re-conquer what had belonged to his ancestor". It is not known who Shapur II thought his ancestor was, probably the Achaemenids or the legendary Kayanids.[5] During the reign of Shapur II, the title of “the divine Mazda-worshipping, king of kings of the Iranians, whose image/seed is from the gods” disappears from the coins that were minted. He was also the last Sasanian king to claim lineage from the gods.[5]

Under Shapur II, coins were minted in copper, silver and gold, however, a great amount of the copper coins were made on Roman planchet, which is most likely from the riches that the Sasanians took from the Romans. The weight of the coins also changed from 7.20 g to 4.20 g.[5]

Constructions

Besides the construction of the war-i tāzigān near al-Hira, Shapur II is also known to have created several other cities. He created a royal city called Eranshahr-Shapur, where he settled Roman prisoners of war. He also rebuilt and repopulated Nisibis in 363 with people from Istakhr and Spahan. In Asoristan, he founded Wuzurg-Shapur ("Great Shapur"), a city on the west side of the Tigris river. He also rebuilt Susa after having destroyed it when suppressing a revolt, renaming it Eran-Khwarrah-Shapur ("Iran's glory [built by] Shapur").[5][6]

Contributions

Under Shapur II's reign the collection of the Avesta was completed, heresy and apostasy punished, and the Christians persecuted (see Abdecalas, Acepsimas of Hnaita and Aba of Kashkar). This was a reaction against the Christianization of the Roman Empire by Constantine I. He was successful in the east, and the great town Nishapur in Khorasan (eastern Parthia) was founded by him. He founded some other towns as well.

References

- ↑ Tafazzoli 1983, p. 477.

- 1 2 Al-Tabari 1991, p. 50.

- ↑ Shahbazi 2004, pp. 461-462.

- 1 2 Daryaee 2009, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Daryaee 2009.

- 1 2 Frye 1983, p. 136.

- ↑ Potts 2012.

- 1 2 3 Touraj Daryaee (2009), Sasanian Persia, London and New York: I.B.Tauris, p. 17

- 1 2 3 4 Touraj Daryaee (2009), Sasanian Persia, London and New York: I.B.Tauris, p. 19

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, p. 58.

Sources

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008), Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, London and New York: I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3

- Daryaee, Touraj (2009). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 0857716662.

- Shapur Shahbazi, A. (2005). "SASANIAN DYNASTY". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Tafazzoli, Ahmad (1989). "BOZORGĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. Ahmad Tafazzoli. p. 427.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2009). "SHAPUR II". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2004). "HORMOZD (2)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 461–462.

- Tafazzoli, Ahmad (1983). "ĀDUR NARSEH". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 5. p. 477.

- Potts, Daniel T. (2012). "ARABIA ii. The Sasanians and Arabia". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1991). Yar-Shater, Ehsan, ed. The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume V: The Sasanids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids, and Yemen. Trans. Clifford Edmund Bosworth. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-0493-5.

| Shapur II | ||

| Preceded by Adur Narseh |

King of kings of Iran and Aniran

309–379 |

Succeeded by Ardashir II |

| ||||||||||

|