Udham Singh

| Udham Singh | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

26 December 1899 Sunam, Punjab, British India |

| Died |

31 July 1940 (aged 40) Pentonville Prison, United Kingdom |

| Organization | Ghadar Party, Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, Indian Workers' Association |

| Movement | Indian Independence movement |

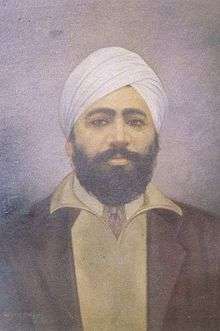

Shaheed Udham Singh (26 December 1899 – 31 July 1940) was an Indian revolutionary best known for assassinating Michael O'Dwyer on 13 March 1940 in what has been described as an avenging of the Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre.[1] Singh is a prominent figure of the Indian independence struggle. He is sometimes referred to as Shaheed-i-Azam Sardar Udham Singh Kamboj (the expression "Shaheed-i-Azam," Urdu: شهید اعظم, means "the great martyr"). A district (Udham Singh Nagar) of Uttarakhand is named after him.

Early life

Singh was born Sher Singh on 26 December 1899, at Sunam in the Sangrur district of Punjab, India, to a sikh family.[2] His father, Sardar Tehal Singh Jammu (known as Chuhar Singh before taking the Amrit), was a railway crossing watchman in the village of Upalli. His mother died in 1901, and his father in 1907.

After his father's death, Singh and his elder brother, Mukta Singh, were taken in by the Central Khalsa Orphanage Putlighar in Amritsar. At the orphanage, Singh was administered the Sikh initiatory rites and received the name of Udham Singh. He passed his matriculation examination in 1918 and left the orphanage in 1919.

Massacre at Jallianwala Bagh

On 10 April 1919, a number of local leaders allied to the Indian National Congress including Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew were arrested under the Rowlatt Act. Protestors against the arrests were fired on by British troops, precipitating a riot during which British banks were burned and four Europeans were killed. On 13 April, over twenty thousand unarmed protestors were assembled in Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar. Singh and his friends from the orphanage were serving water to the crowd.[3]

Troops were dispatched to restore order after the riots, under the command of Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer. Dyer ordered his troops to fire without warning on the assembled crowd in Jallianwala Bagh. Since the only exit was barred by soldiers, people tried to escape by climbing the park walls or jumping into a well for protection. An estimated 379 people were killed and over 1,200 were wounded[4] although that has been debated.[5][6]

Singh was deeply affected by the event. The governor of Punjab, Michael O'Dwyer, had supported the massacre, and Singh held him responsible.[7]

Revolutionary politics

Singh became involved in revolutionary politics and was deeply influenced by Bhagat Singh and his revolutionary group.[8] In 1924, Singh became involved with the Ghadar Party, organizing Indians overseas towards overthrowing colonial rule. In 1927, he returned to India on orders from Bhagat Singh, bringing 25 associates as well as revolvers and ammunition. Soon after, he was arrested for possession of unlicensed arms. Revolvers, ammunition, and copies of a prohibited Ghadar Party paper called "Ghadr-i-Gunj" ("Voice of Revolt") were confiscated. He was prosecuted and sentenced to five years in prison.

Upon his release from prison in 1931, Singh's movements were under constant surveillance by the Punjab police. He made his way to Kashmir, where he was able to evade the police and escape to Germany. In 1934, Singh reached London, where he planned to assassinate Reginald Dyer.[9][10]

Shooting in Caxton Hall

On 13 March 1940, Michael O'Dwyer was scheduled to speak at a joint meeting of the East India Association and the Central Asian Society (now Royal Society for Asian Affairs) at Caxton Hall. Singh concealed his revolver in his jacket pocket (which he received from Puran Singh Boughan from Malsian, Punjab), entered the hall, and found an open seat. As the meeting concluded, Singh shot O'Dwyer twice as he moved towards the speaking platform, killing him immediately. Others hurt in the shooting include Luis Dane, Lawrence Dundas, 2nd Marquess of Zetland, and Charles Cochrane-Baillie, 2nd Baron Lamington. Singh did not attempt to flee and was arrested on site.[11]

Trial and execution

On 1 April 1940, Singh was formally charged with the murder of Michael O'Dwyer. While awaiting trial in Brixton Prison, Singh went on a 42-day hunger strike and had to be forcibly fed. On 4 June 1940, his trial commenced at the Central Criminal Court, Old Bailey, before Justice Atkinson. When asked about his motivation, Singh explained:

I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it. He was the real culprit. He wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him. For full 21 years, I have been trying to wreak vengeance. I am happy that I have done the job. I am not scared of death. I am dying for my country. I have seen my people starving in India under the British rule. I have protested against this, it was my duty. What a greater honour could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland? [12]

Singh was convicted and sentenced to death. On 31 July 1940, Singh was hanged at Pentonville Prison and buried within the prison grounds.

Reactions

Many Indians regarded Singh's action as justified and an important step in India's struggle to end British colonial rule.

In press statements, Mahatma Gandhi condemned the 10 Caxton Hall shooting saying, "the outrage has caused me deep pain. I regard it as an act of insanity...I hope this will not be allowed to affect political judgement."[13] The Hindustan Socialist Republican Army condemned Mahatma Gandhi's statement, considering it to be a challenge to the Indian Youths.[14]

Pt Jawaharlal Nehru wrote in The National Herald, "[The] assassination is regretted but it is earnestly hoped that it will not have far-reaching repercussions on [the] political future of India."[15] In its 18 March 1940 issue, Amrita Bazar Patrika wrote, "O'Dwyer's name is connected with Punjab incidents which India will never forget".[16]

The Punjab section of Congress in the Punjab Assembly led by Dewan Chaman Lal refused to vote for the Premier's motion to condemn the assassination.[17]

In April 1940, at the Annual Session of the All India Congress Committee held in commemoration of 21st anniversary of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, the youth wing of the Indian National Congress Party displayed revolutionary slogans in support of Singh, applauding his action as patriotic and heroic.[18]

Singh had some support from the international press. The Times of London called him a "fighter for freedom", his actions "an expression of the pent-up fury of the downtrodden Indian people."[19] Bergeret from Rome praised Singh's action as courageous.[20] In March 1940, Indian National Congress leader Jawahar Lal Nehru, condemned the action of Singh as senseless. In 1962, Nehru reversed his stance and applauded Singh with the following published statement: "I salute Shaheed-i-Azam Udham Singh with reverence who had kissed the noose so that we may be free."[21]

Repatriation

In 1974, Singh's remains were exhumed and repatriated to India at the request of MLA Sadhu Singh Thind. Singh Thind accompanied the remains back to India, where the casket was received by Indira Gandhi, Shankar Dayal Sharma and Zail Singh. Udham Singh was later cremated in his birthplace of Sunam in Punjab and his ashes were scattered in the Sutlej river.

Legacy

- A charity dedicated to Singh operates on Soho Road, Birmingham.

- A museum dedicated to Singh is located in Amritsar, near Jallianwala Bagh.

- Singh's weapon, a knife, his diary, and a bullet from the shooting are kept in the Black Museum of Scotland Yard.

- Singh has been the subject of a number of films: Jallian Wala Bagh (1977), Shaheed Uddham Singh (1977), and Shaheed Uddham Singh (2000).

- Udham Singh Nagar district in Uttarakhand is named after Singh.

- Singh is the subject of the 1998 track "Assassin" by Asian Dub Foundation.

References

- ↑ Swami, Praveen (Nov 1997). "Jallianwala Bagh revisited: A look at the actual history of one of the most shocking events of the independence struggle". Frontline. 22 14 (India). pp. 1–14.

- ↑ Religious Dimensions of Indian Nationalism. p. 156.

- ↑ Sikander Singh (2002). Pre-meditated Plan of Jallianwala Massacre and Oath of Revenge, Udham Singh alias Ram Mohammad Singh Azad. p. 139.

- ↑ Stephen Stratford. "British Military & Criminal History".

- ↑ Sikander Singh (2002). Pre-meditated Plan of Jallianwala Massacre and Oath of Revenge, Udham Singh alias Ram Mohammad Singh Azad. p. 139.

- ↑ Swami, Praveen (Nov 1997). "Jallianwala Bagh revisited: A look at the actual history of one of the most shocking events of the independence struggle". Frontline. 22 14 (India). pp. 1–14.

- ↑ Sikander Singh (2002). Pre-meditated Plan of Jallianwala Massacre and Oath of Revenge, Udham Singh alias Ram Mohammad Singh Azad. p. 139.

- ↑ Academy of the Punjab in North America. "Shaheed Udham Singh (1899-1940)".

- ↑ Dr. Fauja Singh (1972). Eminent Freedom Fighters of Punjab. pp. 239–40.

- ↑ Singh, Sikander (1998). Udham Singh, alias, Ram Mohammed Singh Azad: a saga of the freedom movement and Jallianwala Bagh. B. Chattar Singh Jiwan Singh.

- ↑ Murder of Michael O'Dwyer, Udham Singh alias Ram Mohammad Singh Azad, 2002, p 180-181, Prof Sikander Singh

- ↑ CRIM 1/1177, Public Record Office, London, p. 64

- ↑ Harijan, 15 March 1940

- ↑ Singh, Sikander (1998). Udham Singh, alias, Ram Mohammed Singh Azad: a saga of the freedom movement and Jallianwala Bagh. B. Chattar Singh Jiwan Singh. p. 216.

- ↑ National Herald, 15 March 1940.

- ↑ Vinay Lal (May 2008). "Manas: History and Politics, British India - Udham Singh in the Popular Memory". Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ Singh, Sikander (1998). Udham Singh, alias, Ram Mohammed Singh Azad: a saga of the freedom movement and Jallianwala Bagh. B. Chattar Singh Jiwan Singh. p. 300.

- ↑ Manmath Nath Gupta (1970). Bhagat Singh and his Times. Delhi. p. 18.

- ↑ The Times (London). 16 March 1940. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Public and Judicial Department, File No L/P + J/7/3822. 10 Caxton Hall outrage. London: India Office Library and Records. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Singh, Sikander (1998). Udham Singh, alias, Ram Mohammed Singh Azad: a saga of the freedom movement and Jallianwala Bagh. B. Chattar Singh Jiwan Singh. p. 300.

Further reading

- Fenech, Louis E. (October 2002). "Contested Nationalisms; Negotiated Terrains: The Way Sikhs Remember Udham Singh 'Shahid' (1899–1940)". Modern Asian Studies (Cambridge University Press) 36 (4): 827–870. doi:10.1017/s0026749x02004031. JSTOR 3876476. (subscription required)

- An article on Udham Singh—Hero Extraordinary in "The Legacy of The Punjab" by R M Chopra, 1997, Punjabee Bradree, Calcutta.

|

- An article on Udham Singh—Hero Extraordinary in "The Legacy of The Punjab" by R M Chopra, 1997, Punjabee Bradree, Calcutta.