Sergei Lyapunov

| Sergei Mikhailovich Lyapunov | |

|---|---|

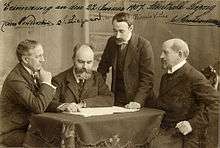

Conductor Hans Winderstein (far left), Sergei Lyapunov, pianist Ricardo Viñes (standing) and publisher Julius Heinrich Zimmermann (far right) in Leipzig in 1907. | |

| Background information | |

| Born |

30 November 1859 Yaroslavl |

| Died |

8 November 1924 (aged 64) Paris |

| Genres | Classical |

| Occupation(s) | Pianist, composer |

| Instruments | Piano |

Sergei Mikhailovich Lyapunov (or Liapunov; Russian: Серге́й Миха́йлович Ляпуно́в, Russian pronunciation: [sʲɪrˈɡʲej mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ lʲɪpʊˈnof]; 30 November [O.S. 18 November] 1859 – 8 November 1924) was a Russian composer and pianist.

Life

Lyapunov was born in Yaroslavl in 1859. After the death of his father, Mikhail Lyapunov, when he was about eight, Sergei, his mother, and his two brothers (one of them was Aleksandr Lyapunov, later a notable mathematician) went to live in the larger town of Nizhny Novgorod. There he attended the grammar school along with classes of the newly formed local branch of the Russian Musical Society. On the recommendation of Nikolai Rubinstein, the Director of the Moscow Conservatory of Music, he enrolled in that institution in 1878. His main teachers were Karl Klindworth (piano; a former pupil of Franz Liszt), and Sergei Taneyev (composition; a former pupil of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and his successor at the Conservatory).

He graduated in 1883, more attracted by the nationalist elements in music of the New Russian School than by the more cosmopolitan approach of Tchaikovsky and Taneyev. He went to St. Petersburg in 1885 to seek Mily Balakirev, becoming the most important member of Balakirev's latter-day circle. Balakirev, who had himself been born and bred in Nizhny Novgorod, took Lyapunov under his wing, and oversaw his early compositions as closely as he had done with the members of his circle during the 1860s, now known as The Five. Balakirev's influence remained the dominant influence in his creative life.[1]

In 1893, the Imperial Geographical Society commissioned Lyapunov, along with Balakirev and Anatoly Lyadov, to gather folksongs from the regions of Vologda, Vyatka (now Kirov) and Kostroma. They collected nearly 300 songs, which the society published in 1897. Lyapunov arranged 30 of these songs for voice and piano and used authentic folk songs in several of his compositions during the 1890s.[1]

He succeeded Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov as assistant director of music at the Imperial Chapel, became a director of the Free Music School, then its head, as well as a professor at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1911. After the Revolution he emigrated to Paris in 1923 and directed a school of music for Russian émigrés, but died of a heart attack the following year. For many years the official Soviet line was that Lyapunov had died during a concert tour of Paris, no acknowledgement being made of his voluntary exile.[2]

Lyapunov enjoyed a successful career as a pianist. He made several tours of Western Europe, including one of Germany and Austria in 1910–1911. From 1904 he also made appearances as a conductor, mounting the podium by invitation in Berlin and Leipzig in 1907.[3]

He is largely remembered for his Douze études d'exécution transcendente. This set completed the cycle of the 24 major and minor keys that Franz Liszt had started with his own Transcendental Études but had left unfinished.[4] Not only was Lyapunov's set of études as a whole dedicated to the memory of Franz Liszt, but the final étude was specifically titled Élégie en memoire de Franz Liszt.

In the spring of 1910 Lyapunov recorded some of his own works for the reproducing piano Welte-Mignon (Op. 11, Nos. 1, 5, and 12; Op. 35).

Selected works

Works with opus numbers

- Op. 1 – Three Pieces

- Etude in D-flat

- Intermezzo in E-flat minor

- Waltz in A-flat major

- Op. 2 – Ballade (orchestra; 1883; also arranged for 2 pianos)

- Op. 3 – Rêverie du soir

- Op. 4 – Piano Concerto No. 1 in E flat minor (1890)

- Op. 5 – Impromptu, A-flat major

- Op. 6 – Seven Preludes

- Op. 7 – Solemn Overture on Russian Themes (1886)

- Op. 8 – Nocturne in D-flat

- Op. 9 – Two Mazurkas (1898)

- Op. 10 – 30 Russian Folksongs

- Op. 11 – 12 Transcendental Études (dedicated to Franz Liszt)

- Berceuse ("Lullaby") in F♯ major

- Ronde des Fantômes ("Ghosts' dance") in D♯ minor

- Carillon in B major

- Térek ("The River Terek") in G♯ minor

- Nuit d'été ("Summer night") in E major

- Tempête ("Tempest") in C♯ minor

- Idylle in A major

- Chant épique ("Epic song") in F♯ minor

- Harpes éoliennes ("Aeolian harps") in D major

- Lesghinka in B minor

- Ronde des sylphes ("Dance of the sylphs") in G major

- Elégie en mémoire de François Liszt ("Elegy in memory of Liszt") in E minor

- Op. 12 – Symphony No. 1 in B minor (1887)[5][6]

- Op. 13 – 35 Russian Folksongs (1897)

- Op. 14 – Four songs

- Op. 15 – Russian songs (1900)

- Op. 16 – Polonaise for Grand Orchestra, in D major (1902) [later arranged (possibly not by the composer?) for piano solo, piano 4h, and 2pf 8h]

- Op. 17 – Mazurka No. 3

- Op. 18 – Novelette

- Op. 19 – Mazurka No. 4

- Op. 20 – Valse pensive

- Op. 21 – Mazurka No. 5

- Op. 22 – Chant du crépuscule

- Op. 23 – Valse-Impromptu No. 1

- Op. 24 – Mazurka No. 6

- Op. 25 – Tarentelle

- Op. 26 – Chant d'automne

- Op. 27 – Piano Sonata in F minor

- Op. 28 – Rhapsody on Ukrainian Themes for piano and orchestra (1907)

- Op. 29 – Valse-Impromptu No. 2

- Op. 30 – Four songs

- Op. 31 – Mazurka No. 7

- Op. 32 – Four songs

- Op. 33 – Two piano pieces from Glinka's Ruslan and Ludmilla

- Fairies' Lullaby

- Combat and Death of Tchernomor

- Op. 34 – Humoresque

- Op. 35 – Divertissements

- Loup-garou

- Le Vautour: jeu d'enfants

- Ronde des enfants

- Colin-maillard

- Chansonette enfantine

- Jeu de course

- Op. 36 – Mazurka No. 8

- Op. 37 – "Zhelazova Vola", symphonic poem in memory of Chopin (Cyrillic, Жeлaзoвa Вoлa; a reference to Chopin's birthplace Żelazowa Wola)

- Op. 38 – Piano Concerto No. 2 in E major (1909)

- Op. 39 – Three Songs

- Op. 40 – Three Pieces

- Prélude

- Elégie

- Humoresque

- Op. 41 – Fêtes de Noël

- Nuit de Noël

- Cortège des mages

- Chanteurs de Noël

- Chant de Noël

- Op. 42 – Three songs (1910–11)

- Op. 43 – Seven songs (1911)

- Op. 44 – Three songs (1911)

- Op. 45 – Scherzo (1911)

- Op. 46 – Barcarolle

- Op. 47 – Five Quartets (male voices)

- Op. 48 – Five Quartets (male voices; 1912)

- Op. 49 – Variations on a Russian Theme (1912)

- Op. 50 – Four songs (1912)

- Op. 51 – Four songs (1912)

- Op. 52 – Four songs (1912)

- Op. 53 – Hashish, an Oriental Symphonic Poem

- Op. 54 – Prelude Pastorale (organ)

- Op. 54b – Prelude Pastorale (arr. 2 pianos) (not confirmed if arrangement is by the composer)

- Op. 55 – Grande Polonaise de Concert (ded. Josef Lhévinne)

- Op. 56 – Four songs (1913)

- Op. 57 – Three Pieces (1913)

- Op. 58 – Prelude and Fugue (1913)

- Op. 59 – Six Easy Pieces

- Jeu de paume (Playing ball)

- Berceuse d'un poupée (Lullaby for a doll)

- Sur une escarpolette (On the swings)

- A cheval sur un bâton (Riding on a stick)

- Conte de la bonne ("La vieille et l'ours") (Nurse’s story)

- Ramage des enfants (Children’s chatter)

- Op. 60 – Variations on a Georgian Theme

- Op. 61 – Violin Concerto (1915; revised 1921)

- Op. 62 – Sacred works (mixed; 1915)

- Op. 63 – Sextet for string quartet, double bass & piano (1915, rev. 1921)

- Op. 64 – Psalm (1916 revised 1923)

- Op. 65 – Sonatina (1917)

- Op. 66 – Symphony No. 2 in B flat (1917)

- Op. 67 – (no work assigned to this number)

- Op. 68 – Vechernyaya pesn [Evening song], Cantata for Tenor, Chorus and Orchestra (1920)

- Op. 69 – Four songs (1919)

- Op. 70 – Valse-Impromptu No. 3

- Op. 71 – Four songs (1919–1920)

Works without opus numbers

- Gifts of the Terek (Дары Терека), Cantata for viola solo, chorus and orchestra (1883)

- 6 Very Easy Pieces (1918–1919)

- Toccata and Fugue (1920)

- Canon (1923)

- Allegretto scherzando (1923)

- 2 Preludes

- Piano transcription of Pachelbel's Canon in D

- Piano transcription of Glinka's "Kamarinskaya"

References

- 1 2 New Grove, 11:385.

- ↑ New Grove, 11:385–386.

- ↑ New Grove, 11:386

- ↑ Hyperion Records, Leslie Howard

- ↑ "Preface to Score of Symphony 1". Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ↑ Spotify. Lyapunov Symphony No1 / Piano Concerto No. 2, BBC Symphony Orchestra. https://open.spotify.com/album/29TvguakRdDCWbcYpOsf9t

Sources

- Garden, Edward, Liner notes for Hyperion CDA 67326, Lyapunov: Piano Concertos 1 & 2; Rhapsody on Ukrainian Themes (London: Hyperion Records Limited, 2002).

- ed. Stanley Sadie, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 20 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1980). ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

External links

- Biography by Dr. David C.F. Wright

- Free scores (in Russian)

- Free scores by Sergei Lyapunov at the International Music Score Library Project

- Richard Beattie Davis `Lyapunov` `Beauty of Belaieff`. G Clef Publishing, Bedford UK 2008 ISBN 978-1-905912-14-8

- worklist at Russisches Musik Archiv

- Lyapunov biography, images, recording list and more by Ryan Layne Whitney

|