Separation axiom

In topology and related fields of mathematics, there are several restrictions that one often makes on the kinds of topological spaces that one wishes to consider. Some of these restrictions are given by the separation axioms. These are sometimes called Tychonoff separation axioms, after Andrey Tychonoff.

The separation axioms are axioms only in the sense that, when defining the notion of topological space, one could add these conditions as extra axioms to get a more restricted notion of what a topological space is. The modern approach is to fix once and for all the axiomatization of topological space and then speak of kinds of topological spaces. However, the term "separation axiom" has stuck. The separation axioms are denoted with the letter "T" after the German Trennungsaxiom, which means "separation axiom."

The precise meanings of the terms associated with the separation axioms has varied over time, as explained in History of the separation axioms. It is important to understand the authors' definition of each condition mentioned to know exactly what they mean, especially when reading older literature.

Preliminary definitions

Before we define the separation axioms themselves, we give concrete meaning to the concept of separated sets (and points) in topological spaces. (Separated sets are not the same as separated spaces, defined in the next section.)

The separation axioms are about the use of topological means to distinguish disjoint sets and distinct points. It's not enough for elements of a topological space to be distinct (that is, unequal); we may want them to be topologically distinguishable. Similarly, it's not enough for subsets of a topological space to be disjoint; we may want them to be separated (in any of various ways). The separation axioms all say, in one way or another, that points or sets that are distinguishable or separated in some weak sense must also be distinguishable or separated in some stronger sense.

Let X be a topological space. Then two points x and y in X are topologically distinguishable if they do not have exactly the same neighbourhoods (or equivalently the same open neighbourhoods); that is, at least one of them has a neighbourhood that is not a neighbourhood of the other (or equivalently there is an open set that one point belongs to but the other point does not).

Two points x and y are separated if each of them has a neighbourhood that is not a neighbourhood of the other; that is, neither belongs to the other's closure. More generally, two subsets A and B of X are separated if each is disjoint from the other's closure. (The closures themselves do not have to be disjoint.) All of the remaining conditions for separation of sets may also be applied to points (or to a point and a set) by using singleton sets. Points x and y will be considered separated, by neighbourhoods, by closed neighbourhoods, by a continuous function, precisely by a function, if and only if their singleton sets {x} and {y} are separated according to the corresponding criterion.

Subsets A and B are separated by neighbourhoods if they have disjoint neighbourhoods. They are separated by closed neighbourhoods if they have disjoint closed neighbourhoods. They are separated by a continuous function if there exists a continuous function f from the space X to the real line R such that the image f(A) equals {0} and f(B) equals {1}. Finally, they are precisely separated by a continuous function if there exists a continuous function f from X to R such that the preimage f−1({0}) equals A and f−1({1}) equals B.

These conditions are given in order of increasing strength: Any two topologically distinguishable points must be distinct, and any two separated points must be topologically distinguishable. Any two separated sets must be disjoint, any two sets separated by neighbourhoods must be separated, and so on.

For more on these conditions (including their use outside the separation axioms), see the articles Separated sets and Topological distinguishability.

Main definitions

These definitions all use essentially the preliminary definitions above.

Many of these names have alternative meanings in some of mathematical literature, as explained on History of the separation axioms; for example, the meanings of "normal" and "T4" are sometimes interchanged, similarly "regular" and "T3", etc. Many of the concepts also have several names; however, the one listed first is always least likely to be ambiguous.

Most of these axioms have alternative definitions with the same meaning; the definitions given here fall into a consistent pattern that relates the various notions of separation defined in the previous section. Other possible definitions can be found in the individual articles.

In all of the following definitions, X is again a topological space.

- X is T0, or Kolmogorov, if any two distinct points in X are topologically distinguishable. (It will be a common theme among the separation axioms to have one version of an axiom that requires T0 and one version that doesn't.)

- X is R0, or symmetric, if any two topologically distinguishable points in X are separated.

- X is T1, or accessible or Fréchet, if any two distinct points in X are separated. Thus, X is T1 if and only if it is both T0 and R0. (Although you may say such things as "T1 space", "Fréchet topology", and "Suppose that the topological space X is Fréchet", avoid saying "Fréchet space" in this context, since there is another entirely different notion of Fréchet space in functional analysis.)

- X is R1, or preregular, if any two topologically distinguishable points in X are separated by neighbourhoods. Every R1 space is also R0.

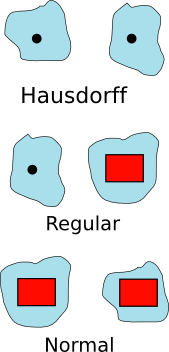

- X is Hausdorff, or T2 or separated, if any two distinct points in X are separated by neighbourhoods. Thus, X is Hausdorff if and only if it is both T0 and R1. Every Hausdorff space is also T1.

- X is T2½, or Urysohn, if any two distinct points in X are separated by closed neighbourhoods. Every T2½ space is also Hausdorff.

- X is completely Hausdorff, or completely T2, if any two distinct points in X are separated by a continuous function. Every completely Hausdorff space is also T2½.

- X is regular if, given any point x and closed set F in X such that x does not belong to F, they are separated by neighbourhoods. (In fact, in a regular space, any such x and F will also be separated by closed neighbourhoods.) Every regular space is also R1.

- X is regular Hausdorff, or T3, if it is both T0 and regular.[1] Every regular Hausdorff space is also T2½.

- X is completely regular if, given any point x and closed set F in X such that x does not belong to F, they are separated by a continuous function. Every completely regular space is also regular.

- X is Tychonoff, or T3½, completely T3, or completely regular Hausdorff, if it is both T0 and completely regular.[2] Every Tychonoff space is both regular Hausdorff and completely Hausdorff.

- X is normal if any two disjoint closed subsets of X are separated by neighbourhoods. (In fact, a space is normal if and only if any two disjoint closed sets can be separated by a continuous function; this is Urysohn's lemma.)

- X is normal Hausdorff, or T4, if it is both T1 and normal. Every normal Hausdorff space is both Tychonoff and normal regular.

- X is completely normal if any two separated sets are separated by neighbourhoods. Every completely normal space is also normal.

- X is completely normal Hausdorff, or T5 or completely T4, if it is both completely normal and T1. Every completely normal Hausdorff space is also normal Hausdorff.

- X is perfectly normal if any two disjoint closed sets are precisely separated by a continuous function. Every perfectly normal space is also completely normal.

- X is perfectly normal Hausdorff, or T6 or perfectly T4, if it is both perfectly normal and T1. Every perfectly normal Hausdorff space is also completely normal Hausdorff.

Relationships between the axioms

The T0 axiom is special in that it can be not only added to a property (so that completely regular plus T0 is Tychonoff) but also subtracted from a property (so that Hausdorff minus T0 is R1), in a fairly precise sense; see Kolmogorov quotient for more information. When applied to the separation axioms, this leads to the relationships in the table below:

| T0 version | Non-T0 version |

|---|---|

| T0 | (No requirement) |

| T1 | R0 |

| Hausdorff (T2) | R1 |

| T2½ | (No special name) |

| Completely Hausdorff | (No special name) |

| Regular Hausdorff (T3) | Regular |

| Tychonoff (T3½) | Completely regular |

| Normal T0 | Normal |

| Normal Hausdorff (T4) | Normal regular |

| Completely normal T0 | Completely normal |

| Completely normal Hausdorff (T5) | Completely normal regular |

| Perfectly normal T0 | Perfectly normal |

| Perfectly normal Hausdorff (T6) | Perfectly normal regular |

In this table, you go from the right side to the left side by adding the requirement of T0, and you go from the left side to the right side by removing that requirement, using the Kolmogorov quotient operation. (The names in parentheses given on the left side of this table are generally ambiguous or at least less well known; but they are used in the diagram below.)

Other than the inclusion or exclusion of T0, the relationships between the separation axioms are indicated in the following diagram:

In this diagram, the non-T0 version of a condition is on the left side of the slash, and the T0 version is on the right side. Letters are used for abbreviation as follows: "P" = "perfectly", "C" = "completely", "N" = "normal", and "R" (without a subscript) = "regular". A bullet indicates that there is no special name for a space at that spot. The dash at the bottom indicates no condition.

You can combine two properties using this diagram by following the diagram upwards until both branches meet. For example, if a space is both completely normal ("CN") and completely Hausdorff ("CT2"), then following both branches up, you find the spot "•/T5". Since completely Hausdorff spaces are T0 (even though completely normal spaces may not be), you take the T0 side of the slash, so a completely normal completely Hausdorff space is the same as a T5 space (less ambiguously known as a completely normal Hausdorff space, as you can see in the table above).

As you can see from the diagram, normal and R0 together imply a host of other properties, since combining the two properties leads you to follow a path through the many nodes on the rightside branch. Since regularity is the most well known of these, spaces that are both normal and R0 are typically called "normal regular spaces". In a somewhat similar fashion, spaces that are both normal and T1 are often called "normal Hausdorff spaces" by people that wish to avoid the ambiguous "T" notation. These conventions can be generalised to other regular spaces and Hausdorff spaces.

Other separation axioms

There are some other conditions on topological spaces that are sometimes classified with the separation axioms, but these don't fit in with the usual separation axioms as completely. Other than their definitions, they aren't discussed here; see their individual articles.

- X is semiregular if the regular open sets form a base for the open sets of X. Any regular space must also be semiregular.

- X is quasi-regular if for any nonempty open set G, there is a nonempty open set H such that the closure of H is contained in G.

- X is fully normal if every open cover has an open star refinement. X is fully T4, or fully normal Hausdorff, if it is both T1 and fully normal. Every fully normal space is normal and every fully T4 space is T4. Moreover, one can show that every fully T4 space is paracompact. In fact, fully normal spaces actually have more to do with paracompactness than with the usual separation axioms.

- X is sober if, for every closed set C that is not the (possibly nondisjoint) union of two smaller closed sets, there is a unique point p such that the closure of {p} equals C. More briefly, every irreducible closed set has a unique generic point. Any Hausdorff space must be sober, and any sober space must be T0.

See also

Sources

- Schechter, Eric (1997). Handbook of Analysis and its Foundations. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0126227608. (has Ri axioms, among others)

- Willard, Stephen (1970). General topology. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. ISBN 0-486-43479-6. (has all of the non-Ri axioms mentioned in the Main Definitions, with these definitions)

- Merrifield, Richard E.; Simmons, Howard E. (1989). Topological Methods in Chemistry. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-83817-9. (gives a readable introduction to the separation axioms with an emphasis on finite spaces)