Semidirect product

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

|

Modular groups

|

Infinite dimensional Lie group

|

In mathematics, specifically in group theory, the concept of a semidirect product is a generalization of a direct product. There are two closely related concepts of semidirect product: an inner semidirect product is a particular way in which a group can be constructed from two subgroups, one of which is a normal subgroup, while an outer semidirect product is a cartesian product as a set, but with a particular multiplication operation. As with direct products, there is a natural equivalence between inner and outer semidirect products, and both are commonly referred to simply as semidirect products.

For finite groups, the Schur–Zassenhaus theorem provides a sufficient condition for the existence of a decomposition as a semidirect product (aka split[ting] extension).

Some equivalent definitions of inner semidirect products

Let G be a group with identity element e, a subgroup H and a normal subgroup N (i.e., N ◁ G).

With this premise, the following statements are equivalent:

- G = NH and N ∩ H = {e}.

- Every element of G can be written in a unique way as a product nh, with n ∈ N and h ∈ H.

- Every element of G can be written in a unique way as a product hn, with h ∈ H and n ∈ N.

- The natural embedding H → G, composed with the natural projection G → G / N, yields an isomorphism between H and the quotient group G / N.

- There exists a homomorphism G → H that is the identity on H and whose kernel is N.

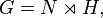

If one (and therefore all) of these statements hold, we say that G is a semidirect product of N and H, written

or that G splits over N; one also says that G is a semidirect product of H acting on N, or even a semidirect product of H and N. To avoid ambiguity, it is advisable to specify which of the two subgroups is normal.

Outer semidirect products

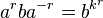

Let G be a semidirect product of the normal subgroup N and the subgroup H. Let Aut(N) denote the group of all automorphisms of N. The map φ : H → Aut(N) defined by φ(h) = φh, where φh(n) = hnh−1 for all h in H and n in N, is a group homomorphism. (Note that hnh−1∈N since N is normal in G.) Together N, H and φ determine G up to isomorphism, as we show now.

Given any two groups N and H (not necessarily subgroups of a given group) and a group homomorphism  : H → Aut(N), we can construct a new group

: H → Aut(N), we can construct a new group  , called the (outer) semidirect product of N and H with respect to φ, defined as follows.[1]

, called the (outer) semidirect product of N and H with respect to φ, defined as follows.[1]

- As a set,

is the cartesian product N × H.

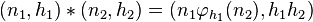

is the cartesian product N × H. - Multiplication of elements in

is determined by the homomorphism

is determined by the homomorphism  . The operation is

. The operation is

- defined by

- for n1, n2 in N and h1, h2 in H.

This defines a group in which the identity element is (eN, eH) and the inverse of the element (n, h) is (φh−1(n−1), h−1). Pairs (n,eH) form a normal subgroup isomorphic to N, while pairs (eN, h) form a subgroup isomorphic to H. The full group is a semidirect product of those two subgroups in the sense given earlier.

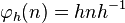

Conversely, suppose that we are given a group G with a normal subgroup N and a subgroup H, such that every element g of G may be written uniquely in the form g = nh where n lies in N and h lies in H. Let φ : H → Aut(N) be the homomorphism given by φ(h) = φh, where

for all n ∈ N,h ∈ H.

Then G is isomorphic to the semidirect product  ; the isomorphism sends the product nh to the tuple (n,h). In G, we have

; the isomorphism sends the product nh to the tuple (n,h). In G, we have

which shows that the above map is indeed an isomorphism and also explains the definition of the multiplication rule in  .

.

The direct product is a special case of the semidirect product. To see this, let φ be the trivial homomorphism, i.e. sending every element of H to the identity automorphism of N, then  is the direct product

is the direct product  .

.

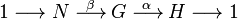

A version of the splitting lemma for groups states that a group G is isomorphic to a semidirect product of the two groups N and H if and only if there exists a short exact sequence

and a group homomorphism γ : H → G such that α ∘ γ = idH, the identity map on H. In this case, φ:H → Aut(N) is given by φ(h) = φh, where

Examples

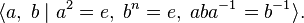

The dihedral group D2n with 2n elements is isomorphic to a semidirect product of the cyclic groups Cn and C2.[2] Here, the non-identity element of C2 acts on Cn by inverting elements; this is an automorphism since Cn is abelian. The presentation for this group is:

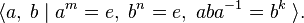

More generally, a semidirect product of any two cyclic groups  with generator

with generator  and

and  with generator

with generator  is given by a single relation

is given by a single relation  with

with  and

and  coprime, i.e. the presentation:[2]

coprime, i.e. the presentation:[2]

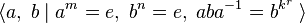

If  and

and  are coprime,

are coprime,  is a generator of

is a generator of  and

and

, hence the presentation:

, hence the presentation:

gives a group isomorphic to the previous one.

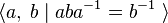

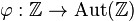

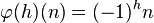

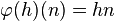

The fundamental group of the Klein bottle can be presented in the form

and is therefore a semidirect product of the group of integers,  , with

, with  . The corresponding homomorphism

. The corresponding homomorphism  is given by

is given by  .

.

The Euclidean group of all rigid motions (isometries) of the plane (maps f : R2 → R2 such that the Euclidean distance between x and y equals the distance between f(x) and f(y) for all x and y in R2) is isomorphic to a semidirect product of the abelian group R2 (which describes translations) and the group O(2) of orthogonal 2×2 matrices (which describes rotations and reflections that keep the origin fixed). Applying a translation and then a rotation or reflection has the same effect as applying the rotation or reflection first and then a translation by the rotated or reflected translation vector (i.e. applying the conjugate of the original translation). This shows that the group of translations is a normal subgroup of the Euclidean group, that the Euclidean group is a semidirect product of the translation group and O(2), and that the corresponding homomorphism  is given by matrix multiplication:

is given by matrix multiplication:  .

.

The orthogonal group O(n) of all orthogonal real n×n matrices (intuitively the set of all rotations and reflections of n-dimensional space which keep the origin fixed) is isomorphic to a semidirect product of the group SO(n) (consisting of all orthogonal matrices with determinant 1, intuitively the rotations of n-dimensional space) and C2. If we represent C2 as the multiplicative group of matrices {I, R}, where R is a reflection of n dimensional space which keeps the origin fixed (i.e. an orthogonal matrix with determinant –1 representing an involution), then φ : C2 → Aut(SO(n)) is given by φ(H)(N) = H N H−1 for all H in C2 and N in SO(n). In the non-trivial case ( H is not the identity) this means that φ(H) is conjugation of operations by the reflection (a rotation axis and the direction of rotation are replaced by their "mirror image").

The group of semilinear transformations on a vector space V over a field  , often denoted

, often denoted  , is isomorphic to a semidirect product of the linear group

, is isomorphic to a semidirect product of the linear group  (a normal subgroup of

(a normal subgroup of  ), and the automorphism group of

), and the automorphism group of  .

.

Properties

As a consequence of Lagrange's theorem, if G is the semidirect product of the normal subgroup N and the subgroup H, and both N and H are finite, then the order of G equals the product of the orders of N and H.

Relation to direct products

Suppose G is a semidirect product of the normal subgroup N and the subgroup H. If H is also normal in G, or equivalently, if there exists a homomorphism G → N which is the identity on N, then G is the direct product of N and H.

The direct product of two groups N and H can be thought of as the semidirect product of N and H with respect to φ(h) = idN for all h in H.

Note that in a direct product, the order of the factors is not important, since N × H is isomorphic to H × N. This is not the case for semidirect products, as the two factors play different roles.

Furthermore, the result of a (proper) semidirect product by means of a non-trivial homomorphism is never an abelian group, even if the factor groups are abelian.

Non-uniqueness of semidirect products (and further examples)

As opposed to the case with the direct product, a semidirect product of two groups is not, in general, unique; if G and G′ are two groups which both contain isomorphic copies of N as a normal subgroup and H as a subgroup, and both are a semidirect product of N and H, then it does not follow that G and G′ are isomorphic because the semidirect product also depends on the choice of an action of H on N.

For example, there are four non-isomorphic groups of order 16 that are [semi]direct product of C8 and C2; C8 is necessarily a normal subgroup in this case because it has index 2 in a group of order 16. One of these four [semi]direct products is the direct product, while the other three are non-abelian groups:

- the dihedral group of order 16

- the quasidihedral group of order 16

- the Iwasawa group of order 16 (M16)

For comparative Cayley diagrams of these see Example 3 in .

If a given group is a semidirect product, then there is no guarantee that this decomposition is unique. For example, there is a group of order 24 (the only one containing six elements of order 4 and six elements of order 6) that can be expressed as semidirect product in the following ways: D8 ⋉ C3 ≃ C2 ⋉ Q12 ≃ C2 ⋉ D12 ≃ D6 ⋉ V.[3]

Existence

In general, there's no known characterization (necessary and sufficient condition) for the existence of semidirect products in groups. However, some sufficient conditions are known, which guarantee existence in certain cases. For finite groups, the Schur–Zassenhaus theorem guarantees existence of a semidirect product when the order of the normal subgroup is coprime to the order of the quotient group.

For example, the Schur–Zassenhaus theorem implies the existence of a semi-direct product among groups of order 6; there are two such products, one of which is a direct product, and the other a dihedral group. In contrast, the Schur–Zassenhaus theorem does not say anything about groups of order 4 or groups of order 8 for instance.

Generalizations

The construction of semidirect products can be pushed much further. The Zappa–Szep product of groups is a generalization which, in its internal version, does not assume that either subgroup is normal. There is also a construction in ring theory, the crossed product of rings. This is seen naturally as soon as one constructs a group ring for a semidirect product of groups. There is also the semidirect sum of Lie algebras. Given a group action on a topological space, there is a corresponding crossed product which will in general be non-commutative even if the group is abelian. This kind of ring (see crossed product for a related construction) can play the role of the space of orbits of the group action, in cases where that space cannot be approached by conventional topological techniques – for example in the work of Alain Connes (cf. noncommutative geometry).

There are also far-reaching generalisations in category theory. They show how to construct fibred categories from indexed categories. This is an abstract form of the outer semidirect product construction.

Groupoids

Another generalization is for groupoids. This occurs in topology because if a group  acts on a space

acts on a space  it also acts on the fundamental groupoid

it also acts on the fundamental groupoid  of the space. The semidirect product

of the space. The semidirect product  is then relevant to finding the fundamental groupoid of the orbit space

is then relevant to finding the fundamental groupoid of the orbit space  . For full details see Chapter 11 of the book referenced below, and also some details in semidirect product[4] in ncatlab.

. For full details see Chapter 11 of the book referenced below, and also some details in semidirect product[4] in ncatlab.

Abelian categories

Non-trivial semidirect products do not arise in abelian categories, such as the category of modules. In this case, the splitting lemma shows that every semidirect product is a direct product. Thus the existence of semidirect products reflects a failure of the category to be abelian.

Notation

Usually the semidirect product of a group H acting on a group N (in most cases by conjugation as subgroups of a common group) is denoted by  or

or  . However, some sources may use this symbol with the opposite meaning. In case the action

. However, some sources may use this symbol with the opposite meaning. In case the action  should be made explicit, one also writes

should be made explicit, one also writes  . One way of thinking about the

. One way of thinking about the  symbol is as a combination of the symbol for normal subgroup (

symbol is as a combination of the symbol for normal subgroup ( ) and the symbol for the product (

) and the symbol for the product ( ).

).

Unicode lists four variants:[5]

value MathML Unicode description ⋉ U+22C9 ltimes LEFT NORMAL FACTOR SEMIDIRECT PRODUCT ⋊ U+22CA rtimes RIGHT NORMAL FACTOR SEMIDIRECT PRODUCT ⋋ U+22CB lthree LEFT SEMIDIRECT PRODUCT ⋌ U+22CC rthree RIGHT SEMIDIRECT PRODUCT

Here the Unicode description of the rtimes symbol says "right normal factor", in contrast to its usual meaning in mathematical practice.

In LaTeX, the commands \rtimes and \ltimes produce the corresponding characters.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Robinson, Derek John Scott (2003). An Introduction to Abstract Algebra. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 75–76. ISBN 9783110175448.

- 1 2 Mac Lane, Saunders; Birkhoff, Garrett (1999). Algebra (3 ed.). American Mathematical Society. pp. 414–415. ISBN 0-8218-1646-2.

- ↑ H.E. Rose (2009). A Course on Finite Groups. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-84882-889-6. Note that Rose uses the opposite notation convention than the one adopted on this page (p. 152).

- ↑ Ncatlab.org

- ↑ See unicode.org

References

- R. Brown, Topology and groupoids, Booksurge 2006. ISBN 1-4196-2722-8