Self-healing material

Self-healing materials are a class of smart materials that have the structurally incorporated ability to repair damage caused by mechanical usage over time. The inspiration comes from biological systems, which have the ability to heal after being wounded. Initiation of cracks and other types of damage on a microscopic level has been shown to change thermal, electrical, and acoustical properties, and eventually lead to wholescale failure of the material. Usually, cracks are mended by hand, which is unsatisfactory because cracks are often hard to detect. A material that can intrinsically correct damage caused by normal usage could lower costs of a number of different industrial processes through longer part lifetime, reduction of inefficiency over time caused by degradation, as well as prevent costs incurred by material failure.[1] For a material to be strictly defined as self-healing, it is necessary that the healing process occurs without human intervention. Some examples shown below, however, include healing polymers that require intervention to initiate the healing process.

Polymer breakdown

From a molecular perspective, traditional polymers yield to mechanical stress through cleavage of sigma bonds.[2] While newer polymers can yield in other ways, traditional polymers typically yield through homolytic or heterolytic bond cleavage. The factors that determine how a polymer will yield include: type of stress, chemical properties inherent to the polymer, level and type of solvation, and temperature.[2]

From a macromolecular perspective, stress induced damage at the molecular level leads to larger scale damage called microcracks.[3] A microcrack is formed where neighboring polymer chains have been damaged in close proximity, ultimately leading to the weakening of the fiber as a whole.[3]

Homolytic bond cleavage

Polymers have been observed to undergo homolytic bond cleavage through the use of radical reporters such as DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and PMNB (pentamethylnitrosobenzene.) When a bond is cleaved homolytically, two radical species are formed which can recombine to repair damage or can initiate other homolytic cleavages which can in turn lead to more damage.[2]

Heterolytic bond cleavage

Polymers have also been observed to undergo heterolytic bond cleavage through isotope labeling experiments. When a bond is cleaved heterolytically, cationic and anionic species are formed which can in turn recombine to repair damage, can be quenched by solvent, or can react destructively with nearby polymers.[2]

Reversible bond cleavage

Certain polymers yield to mechanical stress in an atypical, reversible manner.[4] Diels-Alder-based polymers undergo a reversible cycloaddition, where mechanical stress cleaves two sigma bonds in a retro Diels-Alder reaction. This stress results in additional pi-bonded electrons as opposed to radical or charged moieties.[1]

Supramolecular breakdown

Supramolecular polymers are composed of monomers that interact non-covalently.[5] Common interactions include hydrogen bonds, metal coordination, and van der Waals forces.[5] Mechanical stress in supramolecular polymers causes the disruption of these specific non-covalent interactions, leading to monomer separation and polymer breakdown.

Reversible healing polymers

Reversible systems are polymeric systems that can revert to the initial state whether it is monomeric, oligomeric, or non-cross-linked. Since the polymer is stable under normal condition, the reversible process usually requires an external stimulus for it to occur. For a reversible healing polymer, if the material is damaged by means such as heating and reverted to its constituents, it can be repaired or "healed" to its polymer form by applying the original condition used to polymerize it.

Covalently bonded system

Diels-Alder and retro-Diels-Alder

Among the examples of reversible healing polymers, the Diels-Alder (DA) reaction and its retro-Diels-Alder (RDA) analogue seems to be very promising due to its thermal reversibility. In general, the monomer containing the functional groups such as furan or maleimide form two carbon-carbon bonds in a specific manner and construct the polymer through DA reaction. This polymer, upon heating, breaks down to its original monomeric units via RDA reaction and then reforms the polymer upon cooling or through any other conditions that were initially used to make the polymer. During the last few decades, two types of reversible polymers have been studied: (i) polymers where the pendant groups, such as furan or maleimide groups, cross-link through successive DA coupling reactions; (ii) polymers where the multifunctional monomers link to each other through successive DA coupling reactions.[4]

Cross-linked polymers

In this type of polymer, the polymer forms through the cross linking of the pendant groups from the linear thermoplastics. For example, Saegusa et al. have shown the reversible cross-linking of modified poly(N-acetylethyleneimine)s containing either maleimide or furancarbonyl pendant moideties. The reaction is shown in Scheme 3. They mixed the two complementary polymers to make a highly cross-linked material through DA reaction of furan and maleimide units at room temperature, as the cross-linked polymer is more thermodynamically stable than the individual starting materials. However, upon heating the polymer to 80 °C for two hours in a polar solvent, two monomers were regenerated via RDA reaction, indicating the breaking of polymers.[6] This was possible because the heating energy provided enough energy to go over the energy barrier and results in the two monomers. Cooling the two starting monomers, or damaged polymer, to room temperature for 7 days healed and reformed the polymer.

The reversible DA/RDA reaction is not limited to furan-meleimides based polymers as it is shown by the work of Schiraldi et al. They have shown the reversible cross-linking of polymers bearing pendent anthracene group with maleimides. However, the reversible reaction occurred only partially upon heating to 250 °C due to the competing decomposition reaction.[7]

Polymerization of multifunctional monomers

In this type of polymer, the DA reaction takes place in the backbone itself to construct the polymer, not as a link. For polymerization and healing processes of a DA-step-growth furan-maleimide based polymer (3M4F) were demonstrated by subjecting it to heating/cooling cycles. Tris-maleimide (3M) and tetra-furan (4F) formed a polymer through DA reaction and, when heated to 120 °C, de-polymerized through RDA reaction, resulting in the starting materials. Subsequent heating to 90–120 °C and cooling to room temperature healed the polymer, partially restoring its mechanical properties through intervention.[8][9] The reaction is shown in Scheme 4.

Thiol-based polymers

The thiol-based polymers have disulfide bonds that can be reversibly cross-linked through oxidation and reduction. Under reducing condition, the disulfide (SS) bridges in the polymer breaks and results in monomers, however, under oxidizing condition, the thiols (SH) of each monomer forms the disulfide bond, cross-linking the starting materials to form the polymer. Chujo et al. have shown the thiol-based reversible cross-linked polymer using poly(N-acetylethyleneimine). (Scheme 5) [10]

Poly(urea-urethane)

A soft poly(urea-urethane) network uses the metathesis reaction in aromatic disulphides to provide room-temperature self-healing properties, without the need for external catalysts. This chemical reaction is naturally able to create covalent bonds at room temperature, allowing the polymer to autonomously heal without an external source of energy. Left to rest at room temperature, the material mended itself with 80 percent efficiency after only two hours and 97 percent after 24 hours.

In 2014 a polyurea elastomer-based material was shown to be self-healing, melding together after being cut in half, without the addition of catalysts or other chemicals. The material also include inexpensive commercially available compounds. The elastomer molecules were tweaked, making the bonds between them longer. The resulting molecules are easier to pull apart from one another and better able to rebond at room temperature with almost the same strength. The rebonding can be repeated. Stretchy, self-healing paints and other coatings recently took a step closer to common use, thanks to research being conducted at the University of Illinois. Scientists there have used "off-the-shelf" components to create a polymer that melds back together after being cut in half, without the addition of catalysts or other chemicals.[11][12]

Autonomic polymer healing

Self-healing polymers follow a three-step process very similar to that of a biological response. In the event of damage, the first response is triggering or actuation, which happens almost immediately after damage is sustained. The second response is transport of materials to the effected area, which also happens very quickly. The third response is the chemical repair process. This process differs depending on the type of healing mechanism that is in place. (e.g., polymerization, entanglement, reversible cross-linking). These self-healing materials can be classified in three different ways: capsule based, vascular, and intrinsic (which is listed as “Reversible healing polymers” above). While similar in some ways, these three ways differ in the ways that response is hidden or prevented until actual damage is sustained. Capsule based polymers sequester the healing agents in little capsules that only release the agents if they are ruptured. Vascular self-healing materials sequester the healing agent in capillary type hollow channels which can be interconnected one dimensionally, two dimensionally, or three dimensionally. After one of these capillaries is damaged, the network can be refilled by an outside source or another channel that was not damaged. Intrinsic self-healing materials do not have a sequestered healing agent but instead have a latent self-healing functionality that is triggered by damage or by an outside stimulus.[13]

Thus far, all of the examples on this page require an external stimulus to initiate polymer healing (such as heat or light). Energy is introduced into the system to allow repolymerization to take place. This is not possible for all materials. Thermosetting polymers, for example, are not remoldable. Once they are polymerized (cured), decomposition occurs before the melt temperature is reached. Thus, adding heat to initiate healing in the polymer is not possible. Additionally, thermosetting polymers cannot be recycled, so it is even more important to extend the lifetime of materials of this nature.

Hollow tube approach

For the first method, fragile glass capillaries or fibers are imbedded within a composite material. (Note: this is already a commonly used practice for strengthening materials. See Fiber-reinforced plastic.)[14] The resulting porous network is filled with monomer. When damage occurs in the material from regular use, the tubes also crack and the monomer is released into the cracks. Other tubes containing a hardening agent also crack and mix with the monomer, causing the crack to be healed.[15] There are many things to take into account when introducing hollow tubes into a crystalline structure. First to consider is that the created channels may compromise the load bearing ability of the material due to the removal of load bearing material.[16] Also, the channel diameter, degree of branching, location of branch points, and channel orientation are some of the main things to consider when building up microchannels within a material. Materials that don’t need to withstand much mechanical strain, but want self-healing properties, can introduce more microchannels than materials that are meant to be load bearing.[16] There are two types of hollow tubes: discrete channels, and interconnected channels.[16]

Discrete channels

Discrete channels can be built independently of building the material and are placed in an array throughout the material.[16] When creating these microchannels, one major factor to take into account is that the closer the tubes are together, the lower the strength will be, but the more efficient the recovery will be.[16] A sandwich structure is a type of discrete channels that consists of tubes in the center of the material, and heals outwards from the middle.[17] The stiffness of sandwich structures is high, making it an attractive option for pressurized chambers.[17] For the most part in sandwich structures, the strength of the material is maintained as compared to vascular networks. Also, material shows almost full recovery from damage.[17]

Interconnected networks

Interconnected networks are more efficient than discrete channels, but are harder and more expensive to create.[16] The most basic way to create these channels is to apply basic machining principles to create micro scale channel grooves. These techniques yield channels from 600–700 micrometers.[16] This technique works great on the two-dimensional plane, but when trying to create a three-dimensional network, they are limited.[16]

Direct Ink Writing

The Direct Ink Writing (DIW) technique is a controlled extrusion of viscoelastic inks to create three-dimensional interconnected networks.[16] It works by first setting organic ink in a defined pattern. Then the structure is infiltrated with a material like an epoxy. This epoxy is then solidified, and the ink can be sucked out with a modest vacuum, creating the hollow tubes.[16]

Microcapsule healing

This method is similar in design to the hollow tube approach. Monomer is encapsulated and embedded within the thermosetting polymer. When the crack reaches the microcapsule, the capsule breaks and the monomer bleeds into the crack, where it can polymerize and mend the crack.

A good way to enable multiple healing events is to use living (or unterminated chain-ends) polymerization catalysts. If the walls of the capsule are created too thick, they may not fracture when the crack approaches, but if they are too thin, they may rupture prematurely.[18]

In order for this process to happen at room temperature, and for the reactants to remain in a monomeric state within the capsule, a catalyst is also imbedded into the thermoset. The catalyst lowers the energy barrier of the reaction and allows the monomer to polymerize without the addition of heat. The capsules (often made of wax) around the monomer and the catalyst are important maintain separation until the crack facilitates the reaction.[4][19]

There are many challenges in designing this type of material. First, the reactivity of the catalyst must be maintained even after it is enclosed in wax. Additionally, the monomer must flow at a sufficient rate (have low enough viscosity) to cover the entire crack before it is polymerized, or full healing capacity will not be reached. Finally, the catalyst must quickly dissolve into monomer in order to react efficiently and prevent the crack from spreading further.[19]

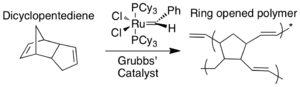

This process has been demonstrated with dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) and Grubbs' catalyst (benzylidene-bis(tricyclohexylphosphine)dichlororuthenium). Both DCPD and Grubbs' catalyst are imbedded in an epoxy resin. The monomer on its own is relatively unreactive and polymerization does not take place. When a microcrack reaches both the capsule containing DCPD and the catalyst, the monomer is released from the core–shell microcapsule and comes in contact with exposed catalyst, upon which the monomer undergoes ring opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP).[19] The metathesis reaction of the monomer involves the severance of the two double bonds in favor of new bonds. The presence of the catalyst allows for the energy barrier (energy of activation) to be lowered, and the polymerization reaction can proceed at room temperature.[20] The resulting polymer allows the epoxy composite material to regain 67% of its former strength.

Grubbs' catalyst is a good choice for this type of system because it is insensitive to air and water, thus robust enough to maintain reactivity within the material. Using a live catalyst is important to promote multiple healing actions.[15] The major drawback is the cost. It was shown that using more of the catalyst corresponded directly to higher degree of healing. Ruthenium is quite costly, which makes it impractical for commercial applications.

Carbon nanotube networks

Through dissolving a linear polymer inside a solid three-dimensional epoxy matrix, so that they are miscible to each other, the linear polymer becomes mobile at a certain temperature[21] When carbon nanotubes are also incorporated into epoxy material, and a direct current is run through the tubes, a significant shift in sensing curve indicates permanent damage to the polymer, thus ‘sensing’ a crack.[22] When the carbon nanotubes sense a crack within the structure, they can be used as thermal transports to heat up the matrix so the linear polymers can diffuse to fill the cracks in the epoxy matrix. Thus healing the material.[21]

SLIPS

A different approach was suggested by Prof. J. Aizenberg from Harvard University, who suggested to use Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces (SLIPS), a porous material inspired by the carnivorous pitcher plant and filled with a lubricating liquid immiscible with both water and oil.[23] SLIPS possess self-healing and self-lubricating properties as well as icephobicity and were successfully used for many purposes.

Sacrificial Thread stitching

Organic threads (such as polylactide filament for example) are stitched through laminate layers of fiber reinforced polymer, which are then boiled and vacuumed out of the material after curing of the polymer, leaving behind empty channels than can be filled with healing agents.[24]

Self-healing in polymers and fibre-reinforced polymer composites

Catalytic liquid-based healing agents

Completely autonomous synthetic self-healing material was reported in 2001 on example of an epoxy system containing microcapsules.[25] These microcapsules were filled with a (liquid) monomer. If a microcrack occurs in this system, the microcapsule will rupture and the monomer will fill the crack. Subsequently it will polymerise, initiated by catalyst particles (Grubbs catalyst) that are also dispersed through the system. This model system of a self healing particle proved to work very well in pure polymers and polymer coatings.

A hollow glass fibre approach may be more appropriate for self-healing impact damage in fibre-reinforced polymer composite materials. Impact damage can cause a significant reduction in compressive strength with little damage obvious to the naked eye. Hollow glass fibres containing liquid healing agents (some fibres carrying a liquid epoxy monomer and some the corresponding liquid hardener) are embedded within a composite laminate. Studies have shown significant potential.[26]

Thermal solid-state healing agents

"Intrinsically" self-healing materials such as supramolecular polymers are formed by reversibly connected non-covalent bonds (i.e. hydrogen bond), which will disassociate at elevated temperatures. Healing of these supramolecullary based materials is accomplished by heating them and allowing the non-covalent bonds to break. Upon cooling, new bonds form and the material heals any damage. An advantage of this method is that no reactive chemicals or (toxic) catalysts are needed. However, these materials are not "autonomic" as they require the intervention of an outside agent to initiate a healing response.

Non-catalytic, non-thermal agents

A poly(urea–urethane) elastomeric network can spontaneously achieve healing in the absence of a catalyst. It is the metathesis reaction of aromatic disulphided (which naturally exchange at room temperature) that causes regeneration. It displayed 97% healing efficiency in just two hours and does not break when stretched manually. The tested poly(urea–urethane) composite is relatively soft.[27][28]

Biomimetics

Self-healing materials are widely encountered in natural systems, and inspiration can be drawn from these systems for design. There is evidence in the academic literature[29] of these biomimetic design approaches being used in the development of self-healing systems for polymer composites.[30] In biology, for the minimum power to pump fluid through vessels Murray's law applies. Deviation from Murray’s law is small however, increasing the diameter 10% only leads to an additional power requirement of 3%–5%. Murray’s law is followed in some mechanical vessels, and using Murray’s law can reduce the hydraulic resistance throughout the vessels.[31] The DIW structure from above can be used to essentially mimic the structure of skin. Toohey et al. did this with an epoxy substrate containing a grid of microchannels containing dicyclopentadiene (DCPD), and incorporated Grubbs' catalyst to the surface. This showed partial recovery of toughness after fracture, and could be repeated several times because of the ability to replenish the channels after use. The process is not repeatable forever, because the polymer in the crack plane from previous healings would build up over time.[32]

Further applications

Self-healing epoxies can be incorporated on to metals in order to prevent corrosion. A substrate metal showed major degradation and rust formation after 72 hours of exposure. But after being coated with the self-healing epoxy, there was no visible damage under SEM after 72 hours of same exposure.[33]

History

Self healing materials only emerged as a widely recognized field of study in the 21st century. The first international conference on self-healing materials was held in 2007.[34] The field of self-healing materials is related to biomimetic materials (materials inspired by living nature) as well as to other novel materials and surfaces with the embedded capacity for self-organization, such as the self-lubricating and self-cleaning materials.[35]

However, some of the simpler applications have been known for centuries, such as the self repair of cracks in concrete. Related processes in concrete have been studied microscopically since the 19th century. A form of self healing mortar was known even to the ancient Romans.[34]

Commercialization

At least two companies are attempting to bring the newer applications of self-healing materials to the market. Arkema, a leading chemicals company, announced in 2009 the beginning of industrial production of self-healing elastomers.[36] As of 2012, Autonomic Materials Inc., had raised over three million US dollars.[37][38]

References

- 1 2 Zang, M.Q. (2008). "Self healing in polymers and polymer composites. Concepts, realization and outlook: A review". Polymer Letters 2 (4): 238–250. doi:10.3144/expresspolymlett.2008.29.

- 1 2 3 4 Caruso, M.; Davis, Douglas A.; Shen, Qilong; Odom, Susan A.; Sottos, Nancy R.; White, Scott R.; Moore, Jeffrey S. (2009). "Mechanically-Induced Chemical Changes in Polymeric Materials". Chem. Rev. 109 (11): 5755–5758. doi:10.1021/cr9001353. PMID 19827748.

- 1 2 Jones, F.R.; Zhang, W.; Branthwaite, M.; Jones, F.R. (2007). "Self-healing of damage in fibre-reinforced polymer-matrix composites". Journal of the Royal Society 4 (13): 381–387. doi:10.1098/rsif.2006.0209. PMC 2359850. PMID 17311783.

- 1 2 3 Bergman, S.D.; Wudl, F. (2008). "Mendable Polymers". Journal of Materials Chemistry 18: 41–62. doi:10.1039/b713953p.

- 1 2 Armstrong, G.; Buggy, M. (2005). "Hydrogen-bonded supramolecules polymers: A literature review". Journal of Materials Science 40 (3): 547–559. Bibcode:2005JMatS..40..547A. doi:10.1007/s10853-005-6288-7.

- 1 2 Chujo, Y.; Sada, K.; Saegusa, T. (1990). "Reversible Gelation of Polyoxazoline by Means of Diels-Alder Reaction". Macromolecules 23 (10): 2636–2641. Bibcode:1990MaMol..23.2636C. doi:10.1021/ma00212a007.

- ↑ Schiraldi, D.A; Liotta, Charles L.; Collard, David M.; Schiraldi, David A. (1999). "Cross-Linking and Modification of Poly(ethylene terephthalate-co-2,6-anthracenedicarboxylate) by Diels−Alder Reactions with Maleimides". Macromolecules 32 (18): 5786–5792. Bibcode:1999MaMol..32.5786J. doi:10.1021/ma990638z.

- 1 2 Wudl, F.; Dam, MA; Ono, K; Mal, A; Shen, H; Nutt, SR; Sheran, K; Wudl, F (2002). "A Thermally Re-mendable Cross-Linked Polymeric Material". Science 295 (5560): 1698–1702. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1698C. doi:10.1126/science.1065879. PMID 11872836.

- ↑ Weizman, Haim; Nielsen, Christian; Weizman, Or S.; Nemat-Nasser, Sia (2011). "Synthesis of a Self-Healing Polymer Based on Reversible Diels–Alder Reaction: An Advanced Undergraduate Laboratory at the Interface of Organic Chemistry and Materials Science". Journal of Chemical Education 88 (8): 1137–1140. doi:10.1021/ed101109f.

- 1 2 Saegusa, T.; Sada, Kazuki; Naka, Akio; Nomura, Ryoji; Saegusa, Takeo (1993). "Synthesis and redox gelation of disulfide-modified polyoxazoline". Macromolecules 26 (5): 883–887. Bibcode:1993MaMol..26..883C. doi:10.1021/ma00057a001.

- ↑ Richard Green (2014-02-15). "Scientists create an inexpensive self-healing polymer". Gizmag.com. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ Ying, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J. (2014). "Dynamic urea bond for the design of reversible and self-healing polymers". Nature Communications 5. doi:10.1038/ncomms4218.

- ↑ Blaiszik, B.J.; Kramer, S.L.B.; Olugebefola, S.C.; Moore, J.S.; Sottos, N.R.; White, S.R. (2010). "Self-Healing Polymers and Composites". Annual Review of Materials Research 40 (1): 179–211. doi:10.1146/annurev-matsci-070909-104532. ISSN 1531-7331.

- ↑ Dry, C. (1996). "Procedures Developed for Self-Repair of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials". Composite Structure 35 (3): 263–264. doi:10.1016/0263-8223(96)00033-5.

- 1 2 Pang, J. W. C.; Bond, I. P. (2005). "A Hollow Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composite Encompassing Self-Healing and Enhanced Damage Visibility". Composite Science and Technology 65 (11–12): 1791–1799. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.03.008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Olugebefola, S. C.; Aragon, A. M.; Hansen, C. J.; Hamilton, A. R.; Kozola, B. D.; Wu, W.; Geubelle, P. H.; Lewis, J. A.; et al. (2010). "Polymer Microvascular Network Composites". Journal of Composite Materials 44 (22): 2587–2603. Bibcode:2010JCoMa..44.2587O. doi:10.1177/0021998310371537. ISSN 0021-9983.

- 1 2 3 Williams, H R; Trask, R S; Bond, I P (2007). "Self-healing composite sandwich structures". Smart Materials and Structures 16 (4): 1198–1207. Bibcode:2007SMaS...16.1198W. doi:10.1088/0964-1726/16/4/031. ISSN 0964-1726.

- ↑ White, S.R.; N. R. Sottos; P. H. Geubelle; J. S. Moore; M. R. Kessler; S. R. Sriram; E. N. Brown; S. Viswanathan (2001-02-15). "Autonomic healing of polymer composites". Nature (PDF) 409 (6822): 794–797. doi:10.1038/35057232. PMID 11236987.

- 1 2 3 White, S. R.; Delafuente, David A.; Ho, Victor; Sottos, Nancy R.; Moore, Jeffrey S.; White, Scott R. (2007). "Solvent-Promoted Self-Healing in Epoxy Materials". Macromolecules 40 (25): 8830–8832. Bibcode:2007MaMol..40.8830C. doi:10.1021/ma701992z.

- ↑ Grubbs, R.; Tumas, W (1989). "Polymerization and Organotransition Metal Chemistry". Science 243 (4893): 907–915. Bibcode:1989Sci...243..907G. doi:10.1126/science.2645643. PMID 2645643.

- 1 2 Hayes, S.A.; Jones, F.R.; Marshiya, K.; Zhang, W. (2007). "A self-healing thermosetting composite material". Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 38 (4): 1116–1120. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2006.06.008. ISSN 1359-835X.

- ↑ Thostenson, E. T.; Chou, T.-W. (2006). "Carbon Nanotube Networks: Sensing of Distributed Strain and Damage for Life Prediction and Self Healing". Advanced Materials 18 (21): 2837–2841. doi:10.1002/adma.200600977. ISSN 0935-9648.

- ↑ Nosonovsky, M. (2011). "Slippery when wetted". Nature 477 (7365): 412–413. Bibcode:2011Natur.477..412N. doi:10.1038/477412a. PMID 21938059.

- ↑ http://beckman.illinois.edu/news/2014/04/self-healing-composites

- ↑ White, SR; Sottos, NR; Geubelle, PH; Moore, JS; Kessler, MR; Sriram, SR; Brown, EN; Viswanathan, S (2001). "Autonomic healing of polymer composites". Nature 409 (6822): 794–7. doi:10.1038/35057232. PMID 11236987.

- ↑ Trask, RS; Williams, GJ; Bond, IP (2007). "Bioinspired self-healing of advanced composite structures using hollow glass fibres". Journal of the Royal Society Interface 4 (13): 363–71. doi:10.1098/rsif.2006.0194. PMC 2359865. PMID 17251131.

- ↑ "‘Terminator’ polymer regenerates itself". KurzweilAI. 2013-09-16. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Rekondo, A.; Martin, R.; Ruiz De Luzuriaga, A.; Cabañero, G. N.; Grande, H. J.; Odriozola, I. (2014). "Catalyst-free room-temperature self-healing elastomers based on aromatic disulfide metathesis". Materials Horizons. doi:10.1039/C3MH00061C.

- ↑ Trask, R S; Williams, H R; Bond, I P (2007). "Self-healing polymer composites: mimicking nature to enhance performance". Bioinspiration & Biomimetics 2 (1): P1–9. Bibcode:2007BiBi....2....1T. doi:10.1088/1748-3182/2/1/P01. PMID 17671320.

- ↑ "Genesys Reflexive (Self-Healing) Composites". Cornerstone Research Group. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ↑ Bond, I.P.; Weaver, P.M.; Trask, R.S.; Williams, H.R. (2008). "Minimum mass vascular networks in multifunctional materials". Journal of the Royal Society Interface 5 (18): 55–65. doi:10.1098/rsif.2007.1022. ISSN 1742-5689. PMC 2605499. PMID 17426011.

- ↑ Toohey, Kathleen S.; Sottos, Nancy R.; Lewis, Jennifer A.; Moore, Jeffrey S.; White, Scott R. (2007). "Self-healing Materials with Microvascular Networks" (PDF). Nature Materials 6 (8): 581–5. doi:10.1038/nmat1934. PMID 17558429.

- ↑ Yang, Zhao; Wei, Zhang; Le-ping, Liao; Hong-mei, Wang; Wu-jun, Li (2011). "The self-healing composite anticorrosion coating". Physics Procedia 18: 216–221. doi:10.1016/j.phpro.2011.06.084. ISSN 1875-3892.

- 1 2 "First international conference on self-healing materials". Delft University of Technology. 12 April 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ Nosonovsky, M. and Rohatgi, P. (2011). Biomimetics in Materials Science: Self-healing, self-lubricating, and self-cleaning materials. Springer Series in Materials Science. ISBN 978-1-4614-0925-0.

- ↑ "Self-healing elastomer enters industrial production". www.arkema.com. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- ↑ Bourzac, Katherine First Self-Healing Coatings. technologyreview.com. December 12, 2008.

- ↑ Paul Rincon (30 October 2010). "Time to heal: The materials that repair themselves". BBC. Retrieved 19 May 2013.