Secondary crater

Secondary craters are impact craters formed by the ejecta that was thrown out of a larger crater. They sometimes form radial crater chains. In addition, secondary craters are often seen as clusters or rays surrounding primary craters. The study of secondary craters exploded around the mid-twentieth century when researchers studying surface craters to predict the age of planetary bodies realized that secondary craters contaminated the crater statistics of a body's crater count.[1]

Formation

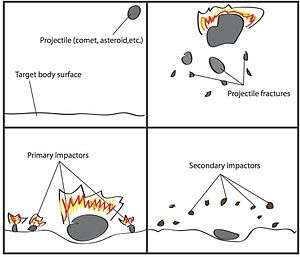

When a velocity-driven extraterrestrial object impacts a relatively stationary body, an impact crater forms. Initial crater(s) to form from the collision are known as primary craters or impact craters. Material expelled from primary craters may form secondary craters (secondaries) under a few conditions:[2]

- Primary craters must already be present.

- The gravitational acceleration of the extraterrestrial body must be great enough to drive the ejected material back toward the surface.

- The velocity by which the ejected material returns toward the body's surface must be large enough to form a crater.

If ejected material is within an atmosphere, such as on Earth, Venus, or Titan, then it is more difficult to retain high enough velocity to create secondary impacts. Likewise, bodies with higher resurfacing rates, such as Io, also do not record surface cratering.[2]

Self-secondary crater

Self-secondary craters are a those that form from ejected material of a primary crater but that are ejected at such an angle that the ejected material makes an impact within the primary crater itself. Self-secondary craters have caused much controversy with scientists who excavate cratered surfaces with the intent to identify its age based on the composition and melt material. An observed feature on Tycho has been interpreted to be a self-secondary crater morphology known as palimpsests.[3][4]

Appearance

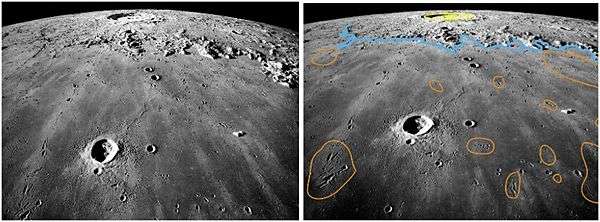

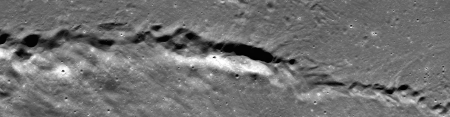

Secondary craters are formed around primary craters.[2] When a primary crater forms following a surface impact, the shock waves from the impact will cause the surface area around the impact circle to stress, forming a circular outer ridge around the impact circle. Ejecta from this initial impact is thrust upward out of the impact circle at an angle toward the surrounding area of the impact ridge. This ejecta blanket, or broad area of impacts from the ejected material, surrounds the crater.[5]

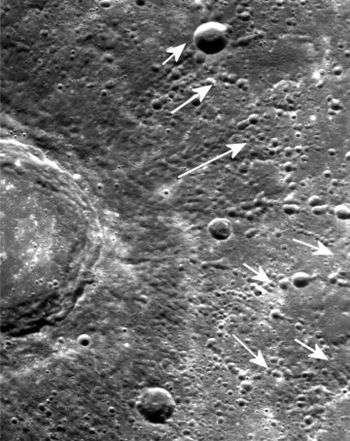

Chains and clusters

Secondary craters may appear as small-scaled singular craters similar to a primary crater with a smaller radius, or as chains and clusters. A secondary crater chain is simply a row or chain of secondary craters lined adjacent to one another. Likewise, a cluster is a population of secondaries near to one another.[6]

Distinguishing factors of primary and secondary craters

Impact energy

Primary craters form from high-velocity impacts whose foundational shock waves must exceed the speed of sound in the target material. Secondary craters occur at lower impact velocities. However, they must still occur at high enough speeds to deliver stress to the target body and produce strain results that exceed the limits of elasticity, that is, secondary projectiles must break the surface.[2]

It can be increasing difficult to distinguish primary craters from secondaries craters when the projectile fractures and breaks apart prior to impact. This depends on conditions in the atmosphere, coupled with projectile velocity and composition. For instance, a projectile that strikes the moon will probably hit intact; whereas if it strikes the earth, it will be slowed and heated by atmospheric entry, possibly breaking up. In that case, the smaller chunks, now separated from the large impacting body, may impact the surface of the planet in the region outside the primary crater, which is where many secondary craters appear following primary surface impact.[7]

Impact angle

For primary impacts, based on geometry, the most probable impact angle is 45° between two objects, and the distribution falls off rapidly outside of the range 30° – 60°.[8] It is observed that impact angle has little effect on the shape of primary craters, except in the case of low angle impacts, where the resulting crater shape becomes less circular and more elliptical.[9] The primary impact angle is much more influential on the morphology (shape) of secondary impacts. Experiments conducted from lunar craters suggests that the ejection angle is at its highest for the early-stage ejecta, that which is ejected from the primary impact at its earliest moments, and that the ejection angle decreases with time for the late-stage ejecta. For example, a primary impact that is vertical to the body surface may produce early-stage ejection angles of 60°-70°, and late-stage ejection angles that have decreases to nearly 30°.[2]

Target type

Mechanical properties of a target's regolith (existing loose rocks) will influence the angle and velocity of ejecta from primary impacts. Research using simulations has been conducted that suggest that a target body's regolith decreases the velocity of ejecta. Secondary crater sizes and morphology also are affected by the distribution of rock sizes in the regolith of the target body.[2][10]

Projectile type

The calculation of depth of secondary crater can be formulated based on the target body's density. Studies of the Nördlinger Ries in Germany and of ejecta blocks circling lunar and martian crater rims suggest that ejecta fragments having a similar density would likely express the same depth of penetration, as opposed to ejecta of differing densities creating impacts of varying depths, such as primary impactors, i.e. comets and asteroids.[2]

Size and Morphology

Secondary crater size is dictated by the size of its parent primary crater. Primary craters can vary from microscopic to thousands of kilometers wide. The morphology of primary craters ranges from bowl-shaped to large, wide basins, where multi-ringed structures are observed. Two factors dominate the morphologies of these craters: material strength and gravity. The bowl-shaped morphology suggests that the topography is supported by the strength of the material, while the topography of the basin-shaped craters is overcome by gravitational forces and collapses toward flatness. The morphology, and size, of secondary craters is limited. Secondary craters exhibit a maximum diameter of < 5% of its parent primary crater.[2] The size of a secondary crater is also dependent on its distance from its primary. The morphology of secondaries is simple but distinctive. Secondaries that form closer to their primaries appear more elliptical with shallower depths. These may form rays or crater chains. The more distant secondaries appear similar in circularity to their parent primaries, but these are often seen in an array of clusters.[2]

Age constraints due to secondary craters

Scientists have long been collecting data surrounding impact craters from the observation that craters are present all throughout the span of the solar system.[11] Most notably, impact craters are studied for the purposes of estimating ages, both relative and absolute, of planetary surfaces. Dating terrains on planets from the according to density of craters has developed into a thorough technique, however 3 key assumptions control it:[2]

- craters exist as independently, contingent occurrences.

- size frequency distribution (SFD) of primary craters is known.

- cratering rate relative to time is known.

Photographs taken from notable lunar and martian missions have provided scientists the ability to count and log the number of observed craters on each body. These crater count databases are further sorted according to each craters size, depth, morphology, and location.[12][13] The observations and characteristics of both primaries and secondaries are used in distinguishing impact craters within small crater cluster, which are characterized as clusters of craters with a diameter ≤1 km. Unfortunately, age research stemming from these crater databases is restrained due to the pollution of secondary craters. Scientists are finding it difficult to sort out all the secondary craters from the count, as they present false assurance of statistical vigor.[12] Contamination by secondaries is often misused to calculate age constraints due to the erroneous attempts of using small craters to date small surface areas.[2]

References

- ↑ Robbins, Stuart J; Hynek, Brian M (8 May 2014). "The secondary crater population of Mars". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 400 (400): 66–76. Bibcode:2014E&PSL.400...66R. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.05.005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 McEwan, Alfred S.; Bierhaus, Edward B. (31 January 2006). "The Importance of Secondary Cratering to Age Constraints on Planetary Surfaces". The Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Science 34: 535–567. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.34.031405.125018. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ Plescia, J.B. (2015). "Lunar crater forms on melt sheets–Origins and implications for self-secondary cratering and chronology" (PDF). Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ Plescia, J.B.; Robinson, M.S. (2015). "Lunar self-secondary cratering: implications for cratering and chronology" (PDF). Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ David Darling. "ejecta blanket". The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spacecraft. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ↑ "Secondary Cratering" (PDF). 2006. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Bart, Gwendolyn D.; Melosh, H. J. (6 April 2007). "Using lunar boulders to distinguish primary from distant secondary impact craters". Geophysical Research Letters 34 (7). Bibcode:2007GeoRL..34.7203B. doi:10.1029/2007GL029306.

- ↑ Gilbert, Grove Karl (April 1893). The Moon's Face, a study of the origin of its features. Washington: Philosophical Society of Washington. pp. 3843–75. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ Gault, Donald E; Wedekind, John A (13 March 1978). "Experimental studies of oblique impact". Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 3 (9): 3843–3875.

- ↑ Head, James N; Melosh, H. Jay; Ivanov, Boris A (7 November 2002). "Martian Meteorite Launch:High-Speed Ejecta from Small Craters". Science 298: 1752–56. doi:10.1126/science.1077483. PMID 12424385.

- ↑ Xiao, Zhiyong; Strom, Robert G (July 2012). "Problems determining relative and absolute ages using the small crater population". Icarus 220 (1): 254–267. Bibcode:2012Icar..220..254X. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.05.012.

- 1 2 Robbins, Stuart J; Hynek, Brian M; Lillis, Robert J; Bottke, William F (July 2013). "Large impact crater histories of Mars: The effect of different model crater age techniques" (PDF). Icarus 225 (1): 173–184. Bibcode:2013Icar..225..173R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.03.019.

- ↑ "Mars Crater Database Search". Mars Crater Database Search. Retrieved 29 March 2015.