Second Italian War of Independence

| Second Italian War of Independence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the wars of Italian Unification | |||||||||

Napoleon III at the Battle of Solferino, by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier Oil on canvas, 1863 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

French: 170,000 infantry 2,000 cavalry 312 guns Sardinian: 70,000 infantry 4,000 cavalry 90 guns |

Austrian: 220,000 infantry 22,000 cavalry 824 guns | ||||||||

The Second Italian War of Independence, also called the Franco-Austrian War, Austro-Sardinian War or Italian War of 1859 (French: Campagne d'Italie),[1] was fought by the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia against the Austrian Empire in 1859 and played a crucial part in the process of Italian unification.

Background

The Piedmontese, following their defeat by Austria in the First Italian War of Independence, recognised their need for allies. This led Camillo Benso, conte di Cavour, the prime minister of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, to attempt to establish relations with other European powers, partially through Piedmont's participation in the Crimean War. In the peace conference at Paris following the Crimean War, Cavour attempted to bring attention to efforts for Italian unification. He found Britain and France to be sympathetic, but entirely unwilling to go against Austrian wishes, as any movement towards Italian independence would necessarily threaten Austria's territory in Lombardy and Venetia. Private talks between Napoleon III and Cavour after the conference identified Napoleon as the most likely, albeit still uncommitted, candidate for aiding Italy.

On 14 January 1858, Felice Orsini, an Italian, led an attempt on Napoleon III's life. This assassination attempt brought widespread sympathy for the Italian unification effort, and had a profound effect on Napoleon himself, who now was determined to help Piedmont against Austria in order to defuse the wider revolutionary activities that the governments inside Italy might allow to happen in the future. After a covert meeting at Plombières, Napoleon III and Cavour signed a secret treaty of alliance against Austria: France would help Sardinia-Piedmont to fight against Austria if attacked, and Sardinia-Piedmont would then give Nice and Savoy to France in return. This secret alliance served both countries: it helped with the Sardinian (Piedmontese) plan of unification of the Italian peninsula under the House of Savoy, and weakened Austria, a fiery adversary of Napoleon III's French Empire.

Cavour, being unable to get the French help unless the Austrians attacked first, provoked Vienna with a series of military manoeuvers close to the border. Austria issued an ultimatum on 23 April 1859, demanding the complete demobilization of the Sardinian army, and when it was not heeded, Austria started a war with Sardinia (29 April), thus drawing France into the conflict.[2]

Forces

The French army for the Italian campaign had 170,000 soldiers, 2,000 horsemen and 312 guns, half of the whole French army. The army was under the command of Napoleon III, divided into five corps: the I Corps, led by Achille Baraguey d'Hilliers, the II Corps, led by Patrice MacMahon, the III Corps, led by François Certain Canrobert, the IV Corps, led by Adolphe Niel, and the V Corps, led by prince Napoleon. The Imperial Guard was commanded by Auguste Regnaud de Saint-Jean d'Angély.

The Sardinian army had about 70,000 soldiers, 4,000 horsemen and 90 guns. It was divided into five divisions, led by Castelbrugo, Manfredo Fanti, Giovanni Durando, Enrico Cialdini, and Domenico Cucchiari. Two volunteer formations, the Cacciatori delle Alpi and the Cacciatori degli Appennini, were also present. The commander in chief was Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy, supported by Alfonso Ferrero la Marmora.

The Austrian army fielded more men: it was composed of 220,000 soldiers, 824 guns and 22,000 horsemen and was led by Field Marshal Ferenc Graf Gyulay.

The operations

.jpg)

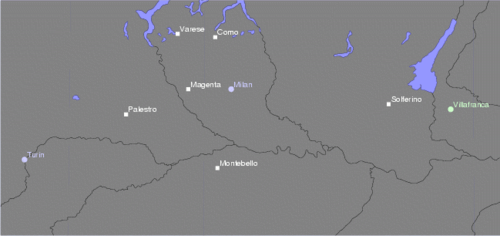

At the declaration of war, there were no French troops in Italy, so Marshal François Certain Canrobert moved into Piedmont in the first massive military use of railways. The Austrian forces counted on a swift victory over the weaker Sardinian army before French forces could arrive in Piedmont. However, Count Gyulai, the commander of the Austrian troops in Lombardy, was very cautious, marching around the Ticino River in no specific direction for a while until eventually crossing it to begin the offensive. Unfortunately for him, very heavy rains began to fall as soon as he did this, allowing the Piedmontese to flood the rice fields in front of his advance, slowing his army's march to a crawl. The Austrians under Gyulai eventually arrived in Vercelli, menacing Turin, but the Franco-Sardinian move to strengthen Alessandria and Po River bridges around Casale Monferrato forced them to fall back. On 14 May Napoleon III arrived in Alessandria, taking the command of the operations. The initial clash of the war was at Montebello on 20 May, a battle between an Austrian Corps under Stadion and a single division of the French I Corps under Forey. The Austrian contingent was three times as large, but the French were victorious, making Gyulai still more cautious. In early June, Gyulai had advanced to the rail center of Magenta, leaving his army spread out. Napoleon III attacked the Ticino head on with part of his force while sending another large group of troops to the north to flank the Austrians. The plan worked, causing Gyulai to retreat east to the quadrilateral fortresses in Lombardy, where he was relieved of his post as commander.

Replacing Gyulai was Emperor Franz Josef I himself. He planned to defend the well-fortified Austrian territory behind the Mincio River. The Piedmontese-French army had taken Milan and slowly marched further east to finish off Austria in this war before Prussia could get involved. The Austrians found out that the French had halted at Brescia, and decided that they should counterattack along the river Chiese. The two armies met accidentally around Solferino, precipitating a confused series of battles. A French corps held off three Austrian corps all day at Medole, keeping them from joining the larger battle around Solferino, where, after a day-long battle, the French broke through. Ludwig von Benedek with the Austrian VIII Corps was separated from the main force, defended Pozzolengo against the Piedmontese part of the opposing army. This they did successfully, but the entire Austrian army retreated after the breakthrough at Solferino, withdrawing back into the Quadrilateral.[3]

At the same time, in the northern part of Lombardy, the Italian volunteers of Giuseppe Garibaldi's Hunters of the Alps defeated the Austrians at Varese and Como and the Piedmontese-French navy landed 3,000 soldiers and conquered the islands of Losinj (Lussino) and Cres (Cherso) in Dalmatia.[4]

The peace

Fear of involvement by the German states led Napoleon to seek a way out of the war, so he signed an armistice with Austria in Villafranca. Most of Lombardy, with its capital Milan (excepting only the Austrian fortresses of Mantua and Legnago and the surrounding territory), was transferred from Austria to France, which would immediately cede these territories to Sardinia. The rulers of Central Italy, who had been expelled by revolution shortly after the beginning of the war, were to be restored.

This deal, made by Napoleon behind the backs of his Sardinian allies, led to great outrage in Sardinia-Piedmont — Cavour himself resigned in protest. However, the terms of Villafranca were never to come into effect: although they were reaffirmed by the final Treaty of Zürich in November, by then the agreement had become a dead letter. The central Italian states were occupied by the Piedmontese, who showed no willingness to restore the previous rulers, and the French showed no willingness to force them to abide by the terms of the treaty. The Austrians were left to look on in frustration at the French failure to carry out the terms of the treaty. While Austria had emerged triumphant after the suppression of liberal movements in 1849, its status as a great power on the European scene was now seriously challenged, and its influence in Italy severely weakened.

The next year, in 1860, with French and British approval, the central Italian states — Duchy of Parma, Duchy of Modena, Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Papal States — were annexed by the Kingdom of Sardinia, and France would take its deferred reward, Savoy and Nice. This latter move was vehemently opposed by Italian national hero Garibaldi, a native of Nice, and directly led to Garibaldi's expedition to Sicily, which would complete the preliminary unification of Italy.[5]

Timeline 1859

- 20 May, French infantry and Sardinian cavalry defeat the Austrian army, which retreated, near Montebello

- 26 May, Giuseppe Garibaldi's Hunters of the Alps confront Austrian forces led by Field Marshal-Lieutenant Carl Baron Urban at Varese

- 27 May, Hunters of the Alps defeat Urban at San Fermo, entering Como

- 30 May, French and Sardinian forces defeat the Austrian army at the Battle of Palestro

- 4 June, in the Battle of Magenta, French defeat Austrians

- 21 June/24 June, in the Battle of Solferino, Sardinians and Napoleon III of France defeat an army commanded by Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph himself in northern Italy. The battle inspires Henri Dunant to found the Red Cross

- 11 July, Franz Joseph, faced with the revolution in Hungary, meets Napoleon III at Villafranca, where they signed an armistice

References

- ↑ Arnold Blumberg, A Carefully Planned Accident: The Italian War of 1859 (Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1990); Arnold Blumberg, "Russian Policy and the Franco-Austrian War of 1859", The Journal of Modern History, 26, 2 (1954): 137–53; Arnold Blumberg, The Diplomacy of the Austro-Sardinian War of 1859, Ph.D. diss. (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pennsylvania, 1952).

- ↑ The Second War of Italian Independence

- ↑ http://www.150anni-lanostrastoria.it/index.php/ii-guerra-indipendenza

- ↑ Luigi Tomaz, In Adriatico nel secondo millennio, Presentazione di Arnaldo Mauri, Think ADV, Conselve, 2010, p. 411.

- ↑ http://www.sapere.it/sapere/strumenti/studiafacile/storia/L-et--contemporanea/Le-Guerre-d-Indipendenza-e-l-unificazione-italiana/La-seconda-Guerra-d-Indipendenza-e-la-spedizione-dei-Mille.html

| ||||||||||||||