Lonnie Mack

| Lonnie Mack | |

|---|---|

Lonnie Mack in Rising Sun, Indiana, 2003. | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Lonnie McIntosh |

| Born |

July 18, 1941 Dearborn County, Indiana, United States |

| Genres | Blues rock, blues, country, southern rock, rockabilly, blue-eyed soul, bluegrass, gospel |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, singer-songwriter |

| Instruments | Vocals, electric guitar, acoustic guitar, bass guitar |

| Years active | 1954–2010 |

| Labels | Alligator, Elektra, Fraternity, Capitol, Flying V Records, Jewel, King, Ace, Epic, Sage Records, Dobbs Records |

| Website |

www |

| Notable instruments | |

| 1958 Gibson Flying V guitar | |

Lonnie McIntosh (born July 18, 1941), known by his stage name, Lonnie Mack, is an American rock, blues, and country singer-guitarist. As a featured artist, his recording career spanned the period 1963-1990. He remained active as a performer into the early 2000s.

Mack was a key figure in making the electric guitar a lead voice in rock music.[1][2] Best known for his 1963 instrumental, "Memphis", he has been called "a pioneer in rock guitar soloing"[3] and a "ground-breaker" in lead guitar virtuosity.[4]

In 1963 and early 1964, he recorded a succession of full-length electric guitar instrumentals which combined blues stylism with fast-picking country techniques and a rock beat. These recordings are said to have formed the leading edge of the "blues rock" lead guitar genre.[5] In 1979, music historian Richard T. Pinnell called 1963's "Memphis" a "milestone of early rock guitar".[6] In 1980, the editors of Guitar World magazine ranked "Memphis" first among rock's top five "landmark" guitar recordings, ahead of recordings by Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Mike Bloomfield.[7] Reportedly, the pitch-bending tremolo arm commonly found on electric guitars became known by the term "whammy bar" in recognition of Mack's aggressive manipulation of the device in 1963's "Wham!".[8]

Mack brought a strong gospel sensibility to his vocals, and is considered one of the finer "blue-eyed soul" singers of his era. Crediting both Mack's vocals and his guitar solos, music critic Jimmy Guterman ranked Mack's first album, The Wham of that Memphis Man!, No. 16 in his book The 100 Best Rock 'n' Roll Records of All Time.[9]

In the late 1950s, while still in his teens, Mack performed on a handful of recordings by other artists. Between 1963 and 1990, he released thirteen original albums spanning a variety of genres. Mack switched musical genres and slowed or idled his career as a rock artist for lengthy periods,[10][11] due to an aversion to notoriety,[12] disenchantment with the music business[13] and a preference for the simpler, less public, country lifestyle of his youth.[14] He enjoyed his greatest popular recognition, and was most productive as a recording artist, during the 1960s and the latter half of the 1980s.

Career

Lonnie Mack's music career began in the mid-1950s. It included historically significant recordings, critical and popular recognition, and periods of reclusion, rediscovery, and comeback. While successful, he never achieved commercial superstardom.[15][16][17] His final album, Attack of the Killer V, was released in 1990. More recently, he has come to be regarded as an "unsung hero" of early rock guitar.[18]

In the early 1960s, Mack augmented the electric blues guitar genre with fast-picking techniques borrowed from traditional country and bluegrass styles, leading one early reviewer to puzzle over the "peculiar running quality" of Mack's bluesy solos.[19] These recordings prefigured the fast, flashy, blues-based lead guitar style which dominated rock by the late 1960s.[1][6][16][20]

By the 1980s, Mack was recognized as a pioneer of virtuoso rock guitar. According to Guitar World magazine, Mack's early solos influenced every major rock guitar soloist of the the mid-Twentieth Century, "from Clapton to Allman to Vaughan"[17] and "from Nugent to Bloomfield".[21]

Although better-known as a guitarist, Mack was a double-threat performer from the outset. A 1968 feature article in Rolling Stone magazine rated Mack a better gospel singer than Elvis Presley,[19] who earned all of his Grammys as a gospel singer.[22] Several of his vocals remain notable for their gospel-like fervor.[19][23]

Mack's recordings drew on rural and urban blues, country, bluegrass, rockabilly, vintage R&B, soul, and gospel styles. Attempts to classify Mack's music proved challenging,[11][24][25][26] but the common thread throughout Mack's best-known music is a unique mix of black and white musical roots, later dubbed "roadhouse rock".[25][26][27] Writing for Rolling Stone, Alec Dubro summarized: "Lonnie can be put into that 'Elvis Presley-Roy Orbison-Early Rock' bag, but mostly for convenience. In total sound and execution, he was an innovator."[28]

Mack's final commercial album as a featured artist, "Attack of the Killer V!", was recorded live in 1989. He performed regularly until 2004, and during the next few years appeared occasionally at special events.[20] On November 15, 2008, Mack played "Wham!" at a production of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame honoring Les Paul.[29] On June 5–6, 2010, he performed at a reunion concert with the surviving members of his early-1960s band.[30] In 2011, he released some informally-recorded compositions on his website, including the acoustic blues single "The Times Ain't Right".

Beyond his career as a solo artist, Mack recorded with The Doors, Stevie Ray Vaughan, James Brown, Freddie King, Joe Simon, Ronnie Hawkins, Albert Collins, Roy Buchanan, Dobie Gray and the sons of blues legend Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup, among others.[31]

Mack's managers over the years have included Fraternity Records co-founder Harry Carlson, John Hovekamp[32] and James Webber,[33] formerly an executive with Elektra Records.[34]

Childhood and early influences

In 1941, Mack's family moved from southeastern Kentucky to southern Indiana, where he spent his childhood on a series of small subsistence farms bordering the Ohio River.[35] Although Mack's childhood homes had no electricity, the family had a primitive battery-powered radio and were devotees of "The Grand Ole Opry" radio show. As a child, listening after the rest of the family had gone to bed, Mack became a fan of early R&B and black gospel music.[15][36]

He began playing at the age of 7, using an acoustic guitar he had traded for a bicycle.[37] While still a youngster, he was playing guitar for tips at a hobo jungle near his home and outside of the Nieman Hotel in nearby Aurora, Indiana.[11] Mack has stated, "I started off in bluegrass, before there was rock and roll. My family was like a family band. We sang and harmonized, and Dad played banjo. We were playin' mostly gospel, bluegrass, and old-style country. We played a lot of that old-style Jimmie Rodgers (country singer) and Hank Williams kinda music."[15][38]

Mack's mother was his earliest country guitar and singing influence, and Ralph Trotto, a blind gospel singer, was his earliest musical mentor.[39] One of Trotto's few recordings, Martha Carson's "Satisfied", is also found on Mack's first album, recorded in 1963.[40]

Mack recalls that an uncle "showed me how you could take a Merle Travis sound on guitar and it was very similar to what a lot of the black guys were doing; they just made it a little funkier. It was pretty easy to come over to that once I figured it out."[41] In addition to country guitarist Travis, various sources have observed that Mack's playing shows influences of jazz guitarist Les Paul and blues guitarist T-Bone Walker.[42][43]

Mack has acknowledged R&B artists Jimmy Reed, Ray Charles, Bobby "Blue" Bland and Hank Ballard as musical influences, as well as country singer George Jones and gospel singer Archie Brownlee of The Five Blind Boys of Mississippi.[44][45] Mack recorded tunes by each of these artists. Mack's highest-charting single, 1963's "Memphis", was an instrumental improvisation grounded in the melody of a Chuck Berry tune, "Memphis, Tennessee".[42]

Early career

Mack dropped out of school at the age of 13 after a fight with a teacher.[46] Using a fake ID, he soon began performing in roadhouses in the Cincinnati area.[47]

As a teen-aged solo artist in the late 1950s, Mack recorded a cover of Al Dexter's 1944 western swing hit, "Pistol Packin' Mama" on the Esta label.[48][49] During the same period, Mack played lead guitar for his older cousins, Aubrey Holt and Harley Gabbard, on two recordings, The Stanley Brothers' "Too Late To Cry" and the cousins' own "Hey, Baby". These two singles were released in 1959 on the Sage label.[50] "Pistol-Packin' Mama" and "Too Late To Cry" have been out-of-print for decades. "Hey, Baby", a rockabilly tune with close-harmony bluegrass vocals, was reissued by the German label, Bear Family Records, in 2010[51] and is now available in the U.S.[52]

By the late 1950s, Mack had assembled a band of his own. They performed throughout Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, playing both rockabilly and, increasingly, R&B-tinged rock and roll. He began using the stage-name "Mack" and, for a time, called his band "The Twilighters", a reference to the Hamilton, Ohio club where they had had a steady engagement.[24]

Mack's guitar

In 1958 Mack bought the seventh Gibson Flying V guitar from that model's first-year production run.[53][54] Dubbing it "Number 7", Mack used this guitar almost exclusively during his career.[55] Mack, who is of Scottish and Native American ancestry[53] was attracted to the arrow-shaped instrument because of his ethnic heritage.[24] The 1958 Flying V model is now considered highly collectible, as less than 100 were shipped in that inaugural year. In 2010, Number 7 was featured in Star Guitars - 101 Guitars that Rocked the World.[56] In 2011, it was featured in The Guitar Collection, a $1,500 two-volume set which included a detailed essay and lush photo layout for each of the world's 150 most "elite" and "exceptional" guitars.[57] In 2012, Mack's guitar was included in Rolling Stone's list of "20 Iconic Guitars".[3]

Guitar style and technique

From his first recordings, Mack's rock-guitar style was steeped in the blues. However, he routinely used fast-paced "fingerstyle" and "chicken picking" techniques originating in traditional country and bluegrass styles, reflecting the dominant musical influences of his early childhood.[58]

Mack typically manipulated the whammy bar with the little finger of his right hand, while picking at a 45-degree angle with a pick or the remaining fingers of the same hand, and bending the strings on the fret-board with his left.[59] Mack's pioneering use of "lightning-fast runs"[60] became a hallmark of virtuoso rock guitar by the end of the 1960s.

On most of his early guitar solos, Mack employed a variant of R&B guitarist Robert Ward's distortion technique, using a 1950s-era tube-fired Magnatone amplifier to produce a distinctive "watery" tone. On other tunes he plugged into an organ amplifier to enhance his vibrato with a "rotating, fluttery sound".[61]

"Memphis", "Wham!", and the advent of virtuoso rock guitar soloing

In the early 1960s Mack and his band often worked as session players for Fraternity, a small record label in Cincinnati.[62] There, they played on a number of singles by local R&B artists, including Max Falcon, Beau Dollar and the Coins, Denzil Rice (who, as "Dumpy" Rice, went on to become the piano player in Mack's band), and Cincinnati's leading female R&B trio, The Charmaines.[63] Several of these recordings are found on compilation CDs entitled Lonnie Mack: From Nashville to Memphis (Ace, 2004) and Gigi and the Charmaines (Ace, 2006).

On March 12, 1963,[64] at the end of a recording session backing up The Charmaines, Mack and his band were offered the remaining twenty minutes of studio rental time.[42] Not expecting the tune to be released, Mack recorded a rockabilly/blues guitar instrumental loosely based on the melody of Chuck Berry's 1959 UK vocal hit, "Memphis, Tennessee".[61] He had improvised the guitar solo in a live performance a few years earlier, when another member of the band (who usually sang the tune) missed a club date. Mack's instrumental version was well-received, so he adopted it as part of his live act. The tune featured a then-unique combination of several key elements. As recorded in 1963, it had seven distinct sections, with an unusually fast 12-bar blues solo. "An extended guitar solo exploiting the entire range of the instrument rings in the climax of the song in the fifth section. Lonnie Mack begins this portion by quoting several measures of the riff one octave higher than before. From there, he breaks into his choicest licks, including double-picking and pulling-off techniques — all with driving, complicated rhythms and technical precision".[65]

By the time "Memphis" was first broadcast, in the spring of 1963, Mack had already forgotten the impromptu recording session and was engaged in a nationwide performing tour with singer-songwriter Troy Seals. A friend located him on tour and told him his tune was climbing the charts. In a 1977 interview, Mack recalled, "I was completely taken by surprise. I [hadn't] listened to the radio. I had no idea what was happening".[42][66] By late June "Memphis" had risen to No. 4 on Billboard's R&B chart and No. 5 on Billboard's pop chart.[42] Only the fourth rock guitar instrumental to penetrate Billboard's "Top 5",[67] it was the only top-20 single of Mack's career. According to music historian and guitar professor Richard T. Pinnell, Mack's fast-paced rockabilly-flavored interpretation of blues stylism in "Memphis" was unique in the history of rock guitar soloing to that point, producing a tune that was both "rhythmically and melodically full of fire" and "one of the milestones of early rock and roll guitar".[6] The track sold over one million copies, and was awarded a gold disc by the RIAA.[68]

Still in 1963, Mack released "Wham!", a gospel-inspired guitar instrumental, which reached No. 24 on Billboard's Pop chart in September.[61] He soon recorded [69] several more full-length rock guitar instrumentals, including his own composition,"Chicken Pickin'", and an instrumental version of Dale Hawkins' "Suzie Q".[49][70] Mack used a Bigsby vibrato tailpiece on "Wham!" and several other tunes to achieve sound effects so distinctive for the time that guitarists began calling it the "whammy bar",[24] a term by which the Bigbsy and other vibrato bars are still known.

Although the term "blues-rock" had not yet come into common usage in 1963, "Memphis" came to be widely regarded as one of the earliest genuine hit recordings of the virtuoso blues-rock guitar genre.[71][72][73] "Wham!" soon followed.[49][74]

Mack's influence on other guitarists

Many prominent players across the broad spectrum of popular music were strongly influenced by Mack during their formative years.[75][76] British jazz-rock guitarist Jeff Beck considers Mack a "major influence".[77] As a teenager, blues-rock guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan honed his guitar skills by playing along with "Wham!" so incessantly that his father finally destroyed the record. Vaughan, who said "Wham!" was "the first record I ever owned",[78] simply bought another copy and resumed his practice.[79] Vaughan considered Mack one of his "very big influences"[80] and said, "I got a lot of the fast things I do from Lonnie".[81] In 1987, Vaughan listed Mack first among the guitarists he listened to, both as a youngster, and as an adult.[82] Vaughan covered "Wham!" on his fifth studio album, The Sky Is Crying. He also recorded "Scuttle-Buttin'" and "Rude Mood", both of which are said to have been inspired by Mack's "Chicken Pickin'".[83] As a teenager, seminal Southern Rock lead and slide guitarist Duane Allman played along with his copy of "Memphis", stopping, starting, and slowing the turntable with his foot, until he had mastered the tune.[84] Western Swing guitarist Ray Benson, frontman for eight-time Grammy-winner Asleep at the Wheel, called Mack "my guitar hero".[85] Southern Rock lead-rhythm guitarist Dickey Betts of The Allman Brothers: "Lonnie is one of the greatest players I know of. He's always been a great influence on me".[86] Funk bassist-guitarist Bootsy Collins of Parliament-Funkadelic: "For me, at that time, Lonnie Mack was the master. Every note that mother played, was, like, Man! I would try to mimic all the notes he played. Same thing with (Collins' brother) Cat. A Lonnie Mack song come out, he'd learn it backwards and forwards".[87]

"Blue-eyed soul" ballads

While Mack's first recording successes were instrumentals, his roadhouse performances typically included both vocals and instrumentals, and in 1963 Mack recorded a number of tunes featuring his singing talents.[88] These early "blue-eyed soul" vocal recordings were critically acclaimed. In 1968, Rolling Stone said, "It is truly the voice of Lonnie Mack that sets him apart. [His] songs have a sincerity and intensity that's hard to find anywhere".[89] According to another review:

Ultimately—for consistency and depth of feeling—the best blue-eyed soul is defined by Lonnie Mack's ballads and virtually everything The Righteous Brothers recorded. Lonnie Mack wailed a soul ballad as gutsily as any black gospel singer. The anguished inflections which stamped his best songs ("Why?", "She Don't Come Here Anymore" and "Where There's a Will") had a directness which would have been wholly embarrassing in the hands of almost any other white vocalist.— music critic Bill Millar, 1983 essay "Blue-Eyed Soul: Colour Me Soul"[90]

R&B radio stations throughout the South played Mack's gospel-inspired version of the soul ballad "Where There's a Will" in 1963; eventually, Mack was invited to give a live radio interview with a prominent R&B disc jockey in racially polarized Birmingham, Alabama. Mack recalls that when he appeared at the radio station, the DJ took one look at him and said, "Baby, you're the wrong color" and canceled the interview on the spot.[61][91]

After that, Mack recalls, there was a precipitous drop in the airplay time devoted to his vocal recordings on R&B radio stations.[92] Fraternity reacted by delaying release of one of Mack's signature soul ballads, "Why?" (recorded in 1963), as a single,[93] until 1968,[61] and then only as the "B" side of a rerelease of "Memphis".[49] "Why?" received scant notice and never charted, but was eventually recognized as a "lost masterpiece of rock 'n' roll".[94] In 2009, music critic Greil Marcus called "Why?" a "soul ballad so torturous, so classically structured, that it can uncover wounds of your own. Mack's scream at the end has never been matched. God help us if anyone ever tops it".[95] [96]

Despite the de facto ban of Mack's vocal recordings on R&B radio stations, his 1963 cover version of Jimmy Reed's "Baby, What's Wrong" became a modest crossover pop hit (Billboard Pop, No. 93),[49] particularly in the Midwest, Fraternity's traditional distribution market.[53]

During the 1970s, Mack recorded fewer blues and soul ballads, and more country and rockabilly vocals.[97] Mack's mature singing style, from the 1980s onward, has been variously described as a "country-esque blues voice"[98] and the "impassioned vocal style of a white Hoosier with a touch of Memphis soul".[99] Examples from the 1980s include a rendition of T-Bone Walker's "Stormy Monday",[100] Mack's own soul ballad, "Stop", and a live, gospel-drenched version of Wilson Pickett's "I Found a Love".[101]

The Wham of that Memphis Man!

During 1963, after the release of "Memphis" and "Wham!", Mack returned to the studio several times to cut additional recordings, including instrumentals, vocals and ensemble tunes.[102] In early 1964, Fraternity packaged several of these, along with his 1963 singles, into an album entitled The Wham of that Memphis Man![103]

Mack's guitar instrumentals were blues-based, but unusually rapid, seamless and precise.[61] His vocals were strongly influenced by Black gospel music. All the tunes were backed by bass guitar and drums, and many also featured keyboards and a Stax/Volt-style horn section. The Charmaines provided an R&B backup chorus on several cuts.[19] In The 100 Best Rock 'n' Roll Records of All Time, Jimmy Guterman ranked the album No. 16:

The first of the guitar-hero records is also one of the best. And for perhaps the last time, the singing on such a disc is worthy of the guitar histrionics. Lonnie Mack bent, stroked, and modified the sound of six strings in ways that baffled his contemporaries and served as a guide to future players. His brash arrangements insure that [the album] remains a showcase for songs, not just a platform for showing off. Mack, who produced this album, has never been given credit for the dignified understatement he brought to his workouts.[104]

The Wham of that Memphis Man! was released within weeks of the beginning of the British Invasion. Competing with the likes of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones was an obstacle encountered by many, but Mack faced an additional challenge: As observed by music critic John Morthland, "[All] the superior chops in the world couldn't hide the fact that chubby, country Mack probably had more in common with Kentucky truck drivers than he did with the new rock audience".[105] Mack slowly slipped back into relative obscurity until the late 1960s. The Wham of that Memphis Man! has been reissued at least ten times, most recently in 2008.[106][107][108][109][110][111] However, most of Mack's Fraternity recordings are not found on the album. Fraternity continued to release additional Mack singles during the 1960s, but never issued another album.[49][112] Many of his Fraternity sides, including some alternate takes of tunes released in the 1960s, were first released three or four decades after they were recorded, on a series of Mack compilation albums.[113][114][115]

Historical significance of Mack's guitar solos

In the early 1960s, Mack's extended guitar solos displayed exceptional levels of speed, dexterity and improvisational skill. In Skydog: The Duane Allman Story, guitarist Mike Johnstone recalled the impact of Mack's playing upon rock guitarists in 1963: "Now, at that time, there was a popular song on the radio called 'Memphis' - an instrumental by Lonnie Mack. It was the best guitar-playing I'd ever heard. All the guitar-players were [saying] 'How could anyone ever play that good? That's the new bar. That's how good you have to be now'".[116] Seventeen years later, in July 1980, the editors of Guitar World magazine ranked "Memphis" the premier "landmark" rock guitar recording to date, immediately ahead of full albums featuring blues-rock guitarists Mike Bloomfield, Elvin Bishop, Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton.[7]

Mack has been called a "guitar hero's guitar hero".[117] He had a significant impact on guitarists Jeff Beck,[77] Duane Allman,[84] Stevie Ray Vaughan,[118] Dickey Betts,[119] Neil Young,[120] and Ted Nugent,[121] among others, and profoundly influenced the evolution of rock guitar.[24][122][123]

In all, it is not an exaggeration to say that Lonnie Mack was well ahead of his time....His bluesy solos pre-dated the pioneering blues-rock guitar work of Jeff Beck... Eric Clapton... and Mike Bloomfield... by nearly two years. Considering that they [were] 'before their time', the chronological significance of Lonnie Mack for the world of rock guitar is that much more remarkable.— Brown & Newquist, Legends of Rock Guitar, Hal Leonard Co., 1997, p. 25

[Mack's early work] was an aggressive, sophisticated, original and fully realized sound, developed by a kid from the sticks. It's questionable we'd have incandescent moments like Cream's [1968] rendition of "Crossroads" without Lonnie Mack's ground-breaking arrangements five years earlier.— Sandmel, , Guitar World, May 1984, pp. 55-56

Mack's own assessment is more modest. He views himself as a transitional figure: "I was a bridge-over between the standard country licks in early rock 'n' roll and the screamin' kinda stuff that came later."[38]

Transition period

In the mid-1960s, the public's musical tastes shifted radically due to the initial, "pop" phase of the "British Invasion". However, during the same period, the "folk music" movement in the US and the popularity of Black American musical forms in both the US and the UK expanded the appeal of classic rural and urban blues among young whites of the baby boom generation.

Soon, a handful of predominantly white blues bands rose to prominence, including John Mayall's Bluesbreakers in the UK and The Paul Butterfield Blues Band in the US. During the mid-through-late 1960s, a new generation of electric blues guitarists emerged, including Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page, most of whom were, or soon became, frontmen for blues-based rock bands. The late 1960s witnessed the appearance of many such bands, most of which showcased the virtuosity of their lead guitarists. These included the enormously successful "power trios": Cream and The Jimi Hendrix Experience. By then, blues-rock was recognized as a distinct and powerful force within rock music on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1968, these developments led to the rediscovery of Mack's seminal blues-rock guitar solos of the early 1960s.[124][125]

Still in the mid-1960s, Mack released a succession of new singles on Fraternity, but none charted, and Mack turned to R&B session work. At Cincinnati's premier record label, Syd Nathan's King Records, he played second guitar on a number of King-label recordings by blues singer-guitarist Freddie King, and lead guitar on some King-label recordings by "The Godfather of Soul", James Brown.[106] The uncredited guitar solo on Brown's 1967 instrumental, "Stone Fox", has been attributed to both Mack and Troy Seals.[126][127][128] During the same period, Mack found steady work as a session guitarist for John Richbourg's Soundstage 7 Productions in Nashville, backing soul singer Joe Simon and several other Richbourg R&B acts on Monument Records.[129] He also played lead guitar on several Fraternity recordings of Cincinnati blues singer Albert Washington.[130] Washington's recordings attracted only modest attention at home, but one featuring Mack's guitar ("Turn On The Bright Lights"), reportedly stayed on the pop charts in Japan for several consecutive years[131] and all were later reissued in the UK.[132]

Rediscovery

In 1968, with the blues-rock movement approaching full force, Mack entered into a multi-record deal with Los Angeles' Elektra Records, and relocated to the West Coast. A feature article in the November 1968 issue of Rolling Stone magazine rated Mack "in a class by himself" as a rock guitarist, and compared his R&B vocals favorably with Elvis Presley's best gospel efforts. Rolling Stone urged Elektra to reissue Mack's 5-year-old Fraternity album. Elektra soon obliged, reissuing The Wham of that Memphis Man!, with two additional 1964 tracks, under the title For Collectors Only. Rolling Stone's October 1970 review of For Collectors Only compared Mack's guitar work from the early 1960s to "the best of [Eric] Clapton".

The Wham of that Memphis Man!/For Collectors Only remains Mack's most significant early album. In his review of a 1987 reissue, Gregory Himes of The Washington Post wrote: "With so many roots-rock guitarists trying to imitate this same style, this album sounds surprisingly modern. Not many have done it this well, though."[133]

Elektra years

Mack recorded three new albums with Elektra, Glad I'm in the Band and Whatever's Right (both released in 1969) and The Hills of Indiana (1971).

In the aggregate, the three Elektra albums represented a stark departure from the strengths and stylistic formula represented by Mack's earlier work, previously touted by Rolling Stone. They were eclectic collections of country and soul ballads, blues tunes, and updated versions of earlier recordings. In contrast to The Wham of that Memphis Man, both 1969 albums emphasized Mack's vocals and de-emphasized his guitar work. Only two instrumentals appear on these albums, a full-length blues guitar piece on Glad entitled "Mt. Healthy Blues", and a re-make of "Memphis".

Despite the shift in musical emphasis, Mack's output from this period was relatively well received by music critics. This, from a contemporary assessment of Glad:

Mack's taste and judgment are super-excellent. Every aspect of his guitar bears a direct relationship to the sound and meaning of the song. [H]is voice is strong without straining and of great range and personality. [I]f this isn't the best rock recording of the season, it's the solidest. – Rolling Stone, May 3, 1969, p. 28.

Representative of these two albums were two consecutive vocals on Whatever's Right. Mack sings Willie Dixon's "My Babe" in a soul style typical of that era. Within seconds of the closing measure on that tune, he begins his vocal on "Things Have Gone To Pieces", a country tune previously recorded by George Jones. He repeated the pattern in Glad by performing a country tune, "Old House", and the soul tune, "Too Much Trouble" in sequence.

In addition to his solo dates during this period, he toured with Elektra label-mates The Doors.[134]

Upon completing the 1969 albums, Mack assumed a "Chet Atkins-Eric Clapton role at Elektra, doing studio dates, producing and A&R."[135] During this period, Mack played bass on two tunes included in The Doors' album "Morrison Hotel".[136] In his A&R role, Mack helped to recruit a number of country and blues artists from Nashville, Memphis and Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and Elektra considered the launch of a new label to record them.[137] Mack tried to sign Carole King, but Elektra rejected her, on the grounds that they already had Judy Collins.[117] He also attempted to interest Elektra in gospel singer Dorothy Combs Morrison, formerly lead vocalist for the Edwin Hawkins Singers of "Oh Happy Day" fame. Mack had recorded Morrison singing a gospel-esque version of The Beatles' "Let It Be"; however, management's response was tabled pending negotiations for the label's sale to Warner Brothers,[138] allowing a competing label to grab the initiative and release Aretha Franklin's own gospel version. "That bummed me out"[117] Mack said, and he quit his corporate job.[13]

By that point, Elektra had put together a musical whistle-stop touring group, including Mack, billed as "The Alabama State Troupers and Mount Zion Choir".[139] According to Elektra producer Russ Miller, Mack disappeared six days before the tour was to begin. Miller soon found Mack at a rustic farm in backwoods Kentucky, and urged him to join the tour. Mack refused, citing a nightmare during his last night in Los Angeles, in which he and his family had been pursued by Satan. He told Miller that when he awoke in a sweat, he found his Bible opened to a passage commanding him to "flee from Mount Zion". Miller returned to L.A. without Mack, stating later: "[Lonnie's] a real country boy. [T]hat was it for Lonnie".[140]

Country years

Mack's final Elektra album, The Hills of Indiana, was released in 1971. Foreshadowing the next phase of Mack's career, The Hills of Indiana completed Mack's shift of focus away from high-octane R&B and blues-rock, towards the pastoral, country end of the musical spectrum. The album sold poorly. His contract with Elektra fulfilled, and with the LA music scene in the rear-view mirror, Mack adopted the roles of low-profile country-rock recording artist, sideman, session-player and occasional roadhouse touring performer. His recordings during this period display only rare glimpses of guitar virtuosity. Over the next fourteen years, he slipped back into a state of relative anonymity.[141]

1970s-era record sales aside, Mack's affinity for country music was genuine. At the peak of his popularity as a blues-rocker, he was fond of organizing after-hours country jam sessions with like-minded rock performers. He recalls one such session in the '60s in which he and Janis Joplin sang a duet on the George Jones song, "Things Have Gone To Pieces", while trading guitar licks with Jimi Hendrix and Jerry Garcia.[142]

Years after leaving Los Angeles, Mack commented on his retreat from the rock 'n' roll spotlight before the age of 30: "Seems like every time I get close to really making it, to climbing to the top of the mountain, that's when I pull out. I just pull up and run".[12] The lyrics of several Mack tunes shed further light on the topic. According to two, he yearned for the anonymous, less complicated, country lifestyle of his youth.[143] In another, he equated the pursuit of "fortune and fame" with selling one's soul to Satan.[144] In yet another, he stated simply: "L.A. made me sick."[145]

In 1973, Mack teamed up with Rusty York on an all-acoustic bluegrass LP, Dueling Banjos (QCA No. 304). Unavailable for 35 years, Jewel Records re-issued it on CD in 2009 (JRC 920011). It contains 16 bluegrass standards in a dueling-banjos format, with guitar and fiddle. Mack played guitar on all 16 cuts and provided the sole vocal track (the gospel tune "I'll Fly Away") on this otherwise instrumental album.[146]

In 1974, Mack played lead guitar in Dobie Gray's band. Gray is best known for his hit tunes, "The 'In' Crowd" (later covered by The Ramsey Lewis Trio and others), "Drift Away" and "Loving Arms". Mack's guitar work from this period can be found on Gray's 1974 album Hey, Dixie. Mack wrote or co-wrote four tunes on the album, including the title track.[147] In March 1974, Mack performed as Gray's lead guitarist at the last broadcast of The Grand Ole Opry from Nashville's Ryman Auditorium.

In 1975, Mack was shot during an altercation with an off-duty police officer. His account of the incident is preserved in one of his better-known late-career tunes, "Cincinnati Jail".[148] According to the lyrics of that tune, the officer's unmarked car narrowly missed Mack while he was walking across a city street, whereupon Mack hit it on the fender, shouting "better slow it down!"; the officer stopped, emerged from his car, shot Mack "in the leg", then hauled him before a judge who threw him in jail. Mack recovered, but once again virtually disappeared from the music scene. For the next several years, he rarely performed in public, except at his "Friendship Music Park" in rural southern Indiana, where he showcased bluegrass and traditional country artists.[11]

In 1977, Mack signed with Capitol Records. There, he recorded Home at Last, an album of country ballads and bluegrass tunes. Also in 1977, Mack performed at a "Save the Whales" benefit concert in Japan.[149] In 1978, he recorded another Capitol LP, Lonnie Mack with Pismo. A somewhat faster-paced album, Pismo featured country, southern rock and rockabilly tunes. In 1979, Mack began working on an independent recording project with a friend, producer-songwriter Ed Labunski.[150] The intended result was a country-pop album ultimately entitled South.[151] However, Labunski died in an auto accident before the project was completed, and the album was shelved. Mack released demos from the South project on his own label, Flying V Records, 20 years later. Labunski's death also derailed Mack's and Labunski's plans to produce then-unknown Texas blues-guitar prodigy Stevie Ray Vaughan, who was destined to play a key role in Mack's blues-rock comeback a few years later.[150]

Shortly after Labunski's death, Mack traveled to Canada for a six-month collaboration with American expatriate rockabilly artist Ronnie Hawkins. Hawkins is best known for having founded The Hawks, a popular Canadian roots-rock group which, after Hawkins departure, became Bob Dylan's backup band and, later still, independently famous as The Band. Mack's guitar work from this period can be heard on Hawkins' 1981 solo album, Legend In His Spare Time.[49]

Blues-rock comeback

By the early 1980s, Mack had been largely absent from the rock music scene for over a decade and his visibility as a recording artist had waned considerably. His first album from this period was Live at Coco's, recorded in 1983. It is Mack's only mid-career roadhouse performance preserved on disc. Originally a bootleg recording, Mack sanctioned its commercial release in 1998.[106] On Coco's, Mack and his band can be heard playing familiar tunes from the Fraternity era, lesser-known tunes from the 1970s, tunes which appear on no other album (e.g., "Stormy Monday", "The Things I Used To Do" and "Man From Bowling Green") and tunes which did not appear on his studio albums until several years later (e.g., "Falling Back In Love With You", "Ridin' the Blinds", "Cocaine Blues" and "High Blood Pressure").

Still in 1983, Mack relocated to Texas, where he played regularly at venues in Dallas and Austin. Early in this period, Mack entered into a performing collaboration with Stevie Ray Vaughan. Little known outside of Texas in 1980, Vaughan's own career took off during this period; by 1985 he was an international blues-rock guitar sensation. Mack and Vaughan had first met in 1979,[24] when Mack, acting on a tip from Vaughan's older brother, went to hear him play at a local bar. Vaughan recalled the meeting in a 1985 interview:

I was playin' at the Rome Inn in Austin, and we had just hit the opening chords of "Wham!" when this big guy walked in. He looked just like a great big bear. As soon as I looked at his face, I realized who he was, and naturally he was blown away to hear us doing his song. [W]e talked for a long time that night. [Lonnie said] he wanted to produce us.— Stevie Ray Vaughan, as quoted in Sandmel, "Rock Pioneer Lonnie Mack In Session With Stevie Ray Vaughan", Guitar Player, April 1985, p. 33

Mack and Vaughan became close friends. Despite the generation gap between them, Mack said that he and Vaughan "were always on the same level", describing Vaughan as "an old spirit...in a young man's body".[152] Mack regarded Vaughan as his "little brother" and Vaughan said Mack was "something between a daddy and a brother".[153][154] When Mack was stricken with a lengthy illness in Texas, Vaughan put on a benefit concert to help pay his bills; during Mack's recuperation, Vaughan and his bass-player, Tommy Shannon, personally installed an air-conditioner in Mack's house.[153]

Vaughan said that "Wham!" was "the first record I ever owned",[78] that Mack was "the baddest guitar player I know",[155] and that Mack "really taught me to play guitar from the heart".[156] Vaughan's musical legacy includes four versions of "Wham!"---two solo versions[157] and two dueling-guitar versions with Mack.[158] He also recorded Mack's "If You Have To Know",[159] and an instrumental homage to "Chicken-Pickin", which Vaughan called "Scuttle-Buttin'".[160][161]

Mack signed with Alligator Records in 1984, and, upon recovering from his illness, began working on his blues-rock comeback album, Strike Like Lightning. It became one of the top-selling independent recordings of 1985.[162] Mack and Vaughan co-produced the album. Mack himself composed most of the tunes, which featured his vocals and driving guitar equally. Vaughan played second guitar on most of the album, and traded leads with Mack on "Double Whammy" and "Satisfy Susie". Both played acoustic guitar on Mack's "Oreo Cookie Blues". Strike propelled Mack back into the spotlight at age 44. Much of 1985 found him occupied with a promotional concert tour for Strike which included guest appearances by Vaughan, Ry Cooder and both Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones, among others. Videos of Mack and Vaughan playing cuts from Strike are found on YouTube and similar websites. In 2007, Sony's Legacy label released a 1987 "live" performance of Mack's "Oreo Cookie Blues" featuring Mack and Vaughan trading leads on electric guitar.[163]

The Strike Like Lightning tour culminated in a Carnegie Hall concert billed as Further On Down the Road, a tip of the hat to Mack's 1964 recording by the same title. There, he shared the stage with blues guitar stylist Albert Collins and blues-rock guitar virtuoso Roy Buchanan. The concert was marketed on home video.[164]

Late career

In 1986, Mack recorded another Alligator album, Second Sight, which featured both introspective and up-tempo tunes as well as an instrumental blues jam. In 1988, he moved to Epic Records, where he recorded the critically acclaimed[165] rockabilly album, Roadhouses and Dance Halls, including the autobiographical single, "Too Rock For Country".[49] In 1989, Mack performed on Saturday Night Live, as the special guest of the SNL house band's guitarist.[166]

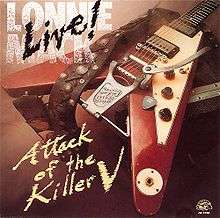

album cover

In 1989, Mack returned to Alligator to record a live blues-rock album, Attack of the Killer V, featuring two extended guitar solos and expanded renditions of earlier studio recordings. From one review: "This disc has everything that a great live album should have: a great talent on stage, an exciting performance from that talent, a responsive crowd and excellent sound quality ... This is what live blues is all about!"[167]

After 2000

Mack continued to tour in both America and Europe until 2004. In 2000, he appeared as a session player on the album Franktown Blues, by the sons of blues legend Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup. Mack provided guitar solos on two cuts, "She's Got The Key" and "Jammin' For James".[168]

In recent years, Mack has occasionally appeared at benefit concerts and special events.[20][169][170] On November 15, 2008, Mack was a featured performer at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 13th annual Music Masters Tribute Concert, soloing on "Wham!" in honor of electric guitar pioneer Les Paul.[29] He has been an occasional surprise sit-in with house bands at roadhouses in rural Tennessee.[171] On June 5–6, 2010, Mack appeared in concert with the surviving members of his original band.[30] In 2011, he was working on a memoir[172] and was engaged in a songwriting collaboration with award-winning country and blues tunesmith Bobby Boyd.[173]

Discography

- 1964: The Wham of that Memphis Man!

- 1969: Glad I'm in the Band

- 1969: Whatever's Right

- 1971: The Hills of Indiana

- 1973: Dueling Banjos (with Rusty York)

- 1977: Home At Last

- 1978: Lonnie Mack With Pismo

- 1980: South (rel. 1999)

- 1983: Live at Coco's (rel. 1999)

- 1985: Strike Like Lightning

- 1986: Second Sight

- 1988: Roadhouses and Dance Halls

- 1990: Attack of the Killer V

- Further info at: http://www.discogs.com/artist/252843-Lonnie-Mack

Career recognition and awards

| Year | Award or recognition |

|---|---|

| 1993 |

|

| 1998 |

|

| 2001 |

|

| 2001 |

|

| 2002 |

|

| 2005 |

|

| 2006 |

|

| 2011 |

|

See also

References

- 1 2 Sandmel, Guitar World, May 1984, pp. 55-56

- ↑ Goldmine Magazine, "When No Words Were Necessary, Pt. 1", December 18, 2010, "Lonnie Mack's brilliant record of Chuck Berry's song, “Memphis”, went to No. 5 in 1963. Mack's hit record is noteworthy, because it pushed a new generation of white kid guitarists in the unaccustomed direction of soul music."

- 1 2 "20 Iconic Guitars Pictures - Lonnie Mack's Flying V". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ "Unsung Guitar Hero: Lonnie Mack". .gibson.com. 1985-07-14. Retrieved 2014-05-18., published 2007-09-05

- ↑ see, e.g., Brown & Newquist, Legends of Rock Guitar, Hal Leonard Co., 1997, p. 25

- 1 2 3 Pinnell, Richard T. (May 1979). "Lonnie Mack's 'Memphis': An Analysis of an Historic Rock Guitar Instrumental". Guitar Player. p. 40.

- 1 2 "Landmark Recordings", Guitar World, July 1980 and July 1990, p. 97

- ↑ McDevitt, "Unsung Guitar Hero Lonnie Mack", Gibson Lifestyle, 2007.

- ↑ Guterman, The Best Rock 'N' Roll Records of All Time, 1992, Citadel Publishing

- ↑ "Account of disappearance from 1968 tour". Answers.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 3 4 Peter Guralnick, "Pickers" column, "Lonnie Mack: Fiery Picker Goes Country" at the Wayback Machine (archived October 28, 2009), 1977, pp. 16, 18; Holzman, Follow The Music, First Media, 2000, pp. 366-67

- 1 2 Peter Guralnick, Pickers, "Lonnie Mack: Fiery Picker Goes Country", 1977, pp. 16-18

- 1 2 Sandmel, "Lonnie Mack is Back on the Track", Guitar World, May 1984, pp. 59-60

- ↑ "Country", 1976: I don't care what you think of me, I'm a-gonna live my life bein' country. Had a fancy job out in Hollywood, everybody said I was doin' good. Had lots of money and opportunities, but I'm a-gonna live my life bein' country.

- 1 2 3 Sandmel, "Lonnie Mack is Back of the Track", Guitar World, May 1984, pp. 55-56

- 1 2 Brown & Newquist, Legends of Rock Guitar, Hal Leonard Pub. Co., 1997, p. 87

- 1 2 Santoro, "Double-Whammy", Guitar World, January 1986, p. 34

- ↑ "Unsung Guitar Hero Lonnie Mack", Gibson Lifestyle, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 Alec Dubro, Review of "The Wham of that Memphis Man!", Rolling Stone, November 23, 1968

- 1 2 3 "Poconut.com". Poconut.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Landmark Recordings", Guitar World, July 1980 and July 1990, p. 97

- ↑ "Donnie Sumner, 'Voice', and Elvis Presley: Elvis Australia". Elvis.com.au. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ see, e.g., Bill Millar, 1983 essay, Blue-Eyed Soul: Colour Me Soul

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Archived May 10, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Peter Watrous, "Lonnie Mack in a Melange of Guitar Styles", New York Times, September 18, 1988

- 1 2 McNutt, Guitar Towns, University of Indiana Press, 2002, p. 174

- ↑ "Lonnie Mack profile at". Rockabillyhall.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Dubro, Rolling Stone, March 23, 1968

- 1 2 John Soeder, The Plain Dealer. "Guitar stars pay tribute to Les Paul in Cleveland concert". cleveland.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 "Lonnie Mack profile at". Facebook. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- ↑ See specific reference to each of these artists footnotes after their names in text of article

- ↑ "Pure Prairie League : View topic - Amagansett LI, 8-7-11". Pureprairieleague.com. 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ Archived November 20, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Russ House, Triad Publishing. "Lonnie Mack's Flying V Music". Lonniemack.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ In a July 24, 2005, interview Mack said, "We was beyond poverty. We was so poor, we didn't know we was poor. But it didn't matter, because we was happy, and we had a loving family. I wouldn't trade it for nothin' in the world. Mom and Dad, y'know, they never had nothin', but we had lots of love. We always had food to eat. We grew big gardens. We killed all the meat we ate. Dad made me a bow and arrow so I could go huntin'. We wouldn't kill 'em for sportsmanship, although that was a proud thing to do. Just for food. And we'd get black walnuts off the trees, and dig out grooves in the maple trees and put buckets on 'em and make some maple candy with the walnuts. Those were our sweet goodies."

- ↑ Archived May 10, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Dan Forte, "Lonnie Mack: That Memphis Man is Back", 1978, p. 20

- 1 2 From transcript of July 24, 2005 interview with Mack.

- ↑ Bill Millar, liner notes to album, "Memphis Wham!" Trotto has been recognized as an influential performer in Southern Indiana. See, record of Trotto's 2001 induction into Southeastern Indiana Musicians Hall of Fame, at:https://www.facebook.com/Southeastern-Indiana-Musicians-Association-INC-1687218718169385/timeline/

- ↑ Compare Mack's recording with Trotto's, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qoLMvkhCDks

- ↑ Van Matre (May 2, 1985). "Lonnie Mack Back In The Swing Of Things". Chicago Tribune, Lifestyle Section. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bill Millar, liner notes to "Memphis Wham!"

- ↑ Dahl, Bill. "Lonnie Mack profile at". allmusic.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Unsung Guitar Hero: Lonnie Mack". .gibson.com. 1985-07-14. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ McNutt, Guitar Towns, University of Indiana Press, 2002, p. 175

- ↑ Russ House, Triad Publishing. "Lonnie Mack bio at". Lonniemack.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Lonnie Mack bio; McNutt, Guitar Towns, University of Indiana Press, 2002, p. 175

- ↑ Bill Millar, liner notes, album "Memphis Wham!"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Mack Discography". Koti.mbnet.fi. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Terry Gordon. "Harley Gabbard discography". Rockin' Country Style. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ↑ Album, "That'll Flat Git It", V. 27, track 17, ISBN 978-3-89916-577-7

- ↑ "That'll Flat Git It! Vol. 27: Rockabilly & Rock 'N' Roll From The Vault Of Sage & Sand Records: Various Artists". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 3 "Lonnie Mack bio data". MusicianGuide.com. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ Meiners, Larry (2001) [2001-03-01]. Flying V: The Illustrated History of this Modernistic Guitar. Flying Vintage Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 0-9708273-3-4.

- ↑ "THE UNIQUE GUITAR BLOG: Lonnie Mack's Flying V". Uniqueguitar.blogspot.com. 2009-12-23. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ Hunter & Gibbons, "Star Guitars", Voyageur Press, 2010

- ↑ "The Guitar Collection" (PDF). Musicroom.com. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ See, Wikipedia article entitled "Blues Rock"; see also, Rubin, "Blues Rock Guitar Heroes", 2014, Hal Leonard Pub. Co., passim and chapter entitled "Wham!"

- ↑ Gene Santoro, "Double Whammy", Guitar World, January 1986, p. 34; Stevie Ray Vaughan: "Nobody can play with a whammy-bar like Lonnie. He holds it while he plays and the sound sends chills up your spine". Nixon, "It's Star Time!", Guitar World, November 1985, p. 82

- ↑ Alec Dubro, writing for Rolling Stone in November 1968 was the first to comment on this aspect of Mack's style, which undoubtedly derives from Mack's early mastery of bluegrass guitar. Dubro noted the "peculiar running quality" of Mack's solos.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bill Millar, liner notes to album "Memphis Wham!"

- ↑ See, album entitled From Nashville to Memphis, Ace, 2001, and liner notes thereto

- ↑ See, albums entitled From Nashville to Memphis (Ace, 2001) and Gigi and the Charmaines (Ace, 2006) and liner notes thereto

- ↑ 1963 Stewart Colman, liner notes to album "From Nashville to Memphis", March 2001

- ↑ Richard T. Pinnell, "Lonnie Mack's Version of Chuck Berry's 'Memphis' — An Analysis of an Historic Rock Guitar Instrumental", Guitar Player Magazine, May 1979, p. 41

- ↑ March 1977 Capitol publicity release entitled "Lonnie Mack"

- ↑ The Virtues, "Guitar Boogie Shuffle" (1959) The Ventures' "Walk, Don't Run" (1960) and Duane Eddy's "Because They're Young" (1960). 1964, Johnny Rivers released his own version of "Memphis", recombining Berry's vocal treatment with signature elements of Mack's instrumental. Rivers' version scored No. 2 on the U.S. Hit Parade.

- ↑ Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. p. 163. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ↑ Russ Miller, liner notes to album For Collectors Only, Elektra EKS-74077, 1970 and "From Nashville to Memphis" Ace CDCHD807

- ↑ Others: "Down in the Dumps", "Nashville", "Tension" and "Lonnie On The Move" in 1963 and "Chicken Pickin'" and "Coastin'" in 1964.

- ↑ Archived June 4, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Talkin' Blues: Lonnie Mack and the Birth of Blues-Rock", Wyatt, December 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Talkin' Blues: Lonnie Mack and the Birth of Blues-Rock". Guitar World. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ Bill Millar, liner notes to album Memphis Wham, Ace, 1999

- ↑ Guterman, The 100 Best Rock 'n' Roll Record of All Time, Citadel, 1992, p. 34; Neil Young: Kent, "Selected Writings on Rock Music", DaCapo Press (2002), p. 299

- ↑ "Sandy Bull". Global Village Idiot. 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 "Jeff Beck profile at". Reference.findtarget.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 DVD, SRV Live at the Mocambo, track 13, Sony, 1991

- ↑ Patoski (1993), "SRV: Caught in the Crossfire", Backbeat: 15–16

- ↑ "The Lost Stevie Ray Vaughan Interview". YouTube. 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ Menn, Secrets From The Masters, Miller-Freeman, Inc, 1992, p. 278, ISBN 0-87930-260-7

- ↑ "Stevie Ray Vaughan - Interview 07/22/87". YouTube. 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ see, e.g., Article entitled "Gnarly Guitar Hall of Fame", by Dan Forte, found within Chapter 3 of Aldrich, "This Old Guitar", Voyager Press, 2003, at p. 101

- 1 2 "Skydog: The Duane Allman Story". Backbeat. 2006. pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Benson interview, VHS/DVD entitled "Further On Down The Road", Flying V, 1985

- ↑ "The Allman Brothers : Live at Clifton Garage 1970" (PDF). Spectratechild.com. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ Interview with Bootsy Collins, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=US1658nBJow

- ↑ Delehant, "Lonnie Mack Four Years After Memphis", Hit Parade, 1967; Bill Millar, liner notes to "Memphis Wham!"

- ↑ Alec Dubrow, Rolling Stone, November 23, 1968) Quote: The guitar, always high and uptight, is backed by and pitted against either the chorus, the saxes, or both. But it is truly the voice of Lonnie Mack that sets him apart. He is primarily a gospel singer, and in a way not too different from, say, Elvis, whose gospel works are both great and largely unnoticed. But where Elvis' singing has always had an impersonal quality, Lonnie's songs have a sincerity and intensity that's hard to find anywhere.

- ↑ Bill Millar (1983). "Blue-eyed Soul: Colour Me Soul". The History of Rock. Archived from the original on 2007-11-22. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Sandmel (May 1984). "Lonnie Mack is Back on the Track". Guitar World. p. 59.

- ↑ Sandmel (May 1984), Lonnie Mack is Back on the Track, Guitar World, p. 59

- ↑ "Why?" did appear on Mack's 1963 album, "The Wham of that Memphis Man"

- ↑ Curtis. Lost Rock & Roll Masterpieces Fortune, 2001-04-30 Quote: "Why?", Mack wails, transforming it into a word of three syllables. "Why-y-y?" It's sweaty slow-dance stuff, with an organ intro, a stinging guitar solo, and, after the last emotional chorus, four simple notes on the guitar as a coda. There's no sadder, dustier, beerier song in all of Rock".

- ↑ Marcus, 2009, lecture entitled, "Songs Left Out of the Ballad of Sexual Dependency", delivered at the 2009 Pop Conference at the Experience Music Project in Seattle.

- ↑ A popular local Minneapolis group, The Accents, had local hits with "Wherever There's A Will" (Garrett 4008) and "Why" (Garrett 4014). Both singles got substantial airplay locally and sold well throughout the state.

- ↑ Compare the vocals on 1963's "The Wham of that Memphis Man!" to those in "Home at Last" and "Lonnie Mack With Pismo", both recorded in the mid-1970s

- ↑ Watrous, "Lonnie Mack in a Melange of Guitar Styles", New York Times, September 18, 1988

- ↑ Francis Davis, History of the Blues, Da Capo, 1995, p. 246

- ↑ "Stormy Monday" is track 12 of the first CD in the set entitled "Live at Coco's". On the same album, hear "Why" and "The Things That I Used To Do"

- ↑ Stop" appears as track 3 of "Strike Like Lightning". A live version of the same tune appears as track 3 of 1990's "Attack of the Killer V".

- ↑ Russ Miller, liner notes to album "For Collectors Only", Elektra EKS-74077; Stuart Colman, 2001 liner notes to "From Nashville to Memphis", with accompanying Fraternity discography

- ↑ See, Track Listing in Wikipedia Article entitled "The Wham Of That Memphis Man".

- ↑ Guterman, The 100 Best Rock 'n' Roll Records of All Time, Citadel, 1992, p. 34

- ↑ John Morthland, "Lonnie Mack", Output, March 1984

- 1 2 3 "WangDangDula.com". Koti.mbnet.fi. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ 1987 reissue, without label reference: Himes, "Lonnie Mack" (column), The Washington Post, February 20, 1987

- ↑ The Wham of tha Memphis Man!, Ace (UK), 2006

- ↑ "Alligator reissue". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Unsung Guitar Hero: Lonnie Mack". Gibson.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ 2008 release on Collectables label, For Collectors Only, a copy of the 1970 Elektra reissue.

- ↑ Comprehensive Mack Fraternity Discography reproduced in tabular form by Ace Records, current owner of Fraternity, in the liner notes to CD "Lonnie Mack: From Nashville to Memphis"

- ↑ See: Ace CDs entitled "Memphis Wham!"

- ↑ "Lonnie Still On The Move" and "Lonnie Mack: From Nashville to Memphis", and comprehensive liner notes to each.

- ↑ See: Flying V's 2-CD set entitled "Direct Hits and Close Calls" and comments re same on Mack's website)

- ↑ Poe, "Skydog: The Duane Allman Story", Backbeat, 2006, p. 10

- 1 2 3 Gettleman, Orlando Sentinel, "Gutiar Hero Lonnie Mack", as reprinted in Salt Lake Tribune, August 3–4, 1993, p. 3

- ↑ Potoski, "SRV: Caught in the Crossfire", Backbeat, 1993, pp. 15-16

- ↑ "Betts 1985 interview". Youtube.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Kent, The Dark Side: Selected Writings on Rock Music, DaCapo, 1995, p. 299

- ↑ "Ted Nugent biography at". Musicianguide.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan Guitar World, November 1985, p. 28. Quote: [T]he way I look at it, we're just giving back to him what he did for all of us. [A] lot of producing is just being there, and with Lonnie, reminding him of his influence on myself and other guitar players. Most of us got a lot from him.

- ↑ Dickey Betts interview on YouTube, "God bless the Beach Boys, but I was really gettin' tired of "Little Deuce Coupe" and all the beach songs, and "Louie, Louie" — which are all great songs, but I'm talkin' about guitar-playin'. And then, here come Lonnie Mack right down the middle of it all. God, what a breath of fresh air that was for me." – Allman Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts

- ↑ Alec Dubrow, Review of "The Wham of that Memphis Man!, Rolling Stone, November 23, 1968;

- ↑ Bill Millar, liner notes to album Memphis Wham!

- ↑ "Stone Fox, an anomaly". mog.com/Spike/blog_post. 2007-04-20. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ "Fab Flipside #7-"Stone Fox" James Brown | The Music Click". Dawn.proboards.com. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ "WangDangDula.com". Koti.mbnet.fi. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ "Swampland.com". Swampland. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ↑ album "Albert Washington, Blues and Soul Man" (Ace, 1999) and liner notes thereto by Steven C. Tracy, Ph. D

- ↑ Steven C. Tracy, Ph.D.: (1) Liner notes to Ace CD "Albert Washington: Blues and Soul Man, with Lonnie Mack" and (2) Going to Cincinnati: A History of the Blues in the Queen City, Univ. Of Illinois Press, 1988, p. 165 et. seq

- ↑ CD entitled "Albert Washington, Blues and Soul Man, with Lonnie Mack", Ace CDCHD 727. (1999)

- ↑ Gregory Himes (1987-02-20). "Lonnie Mack". The Washington Post.

With so many roots-rock guitarists trying to imitate this same style, this album sounds surprisingly modern. Not many have done it this well, though.

- ↑ "Cryptical Developments: The Doors, Lonnie Mack, Elvin Bishop. Cow Palace, 7/25/69". Cryptdev.blogspot.com. 2010-11-07. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ Rolling Stone, "Random Notes", February 7, 1970, p. 4

- ↑ See, original liner notes to the album. While in-studio for that album, The Doors waxed an instrumental entitled "Blues for Lonnie", which was released many years later as a recording session out-take "The Doors Blues For Lonnie (Instrumental) 1969". YouTube. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ Holzman, Follow The Music, First Media, 1998, pp. 366-67

- ↑ Greg Kot (1989-12-13). "He Wrote The Book - tribunedigital-chicagotribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ Holzman, Follow The Music, First Media, 2000, p. 367

- ↑ Holzman, Follow the Music, First Media. 1998, p. 367

- ↑ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. 2009-10-28. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Mike Vinson. "VINSON: ‘The Possum’ has gone to heaven". The Murfreesboro Post. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ "Country", 1976: I don't care what you think of me, I'm a-gonna live my life bein' country. Had a fancy job out in Hollywood, everybody said I was doin' good. Had lots of money and opportunities, but I'm a-gonna live my life bein' country.; hear also: Title track from Mack's 1971 album, "Hills of Indiana"

- ↑ Song: "A Song I Haven't Sung", track 10 on album "Second Sight", Alligator, 1986

- ↑ "A Long Way From Memphis", track 4 on "Strike Like Lightning" album, Alligator (1985)

- ↑ Staff (2005-06-19). "Lonnie Mack teams up with Rusty York". Tradebit.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Planer, Lindsay. "Hey Dixie - Dobie Gray". AllMusic. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ A studio version of the tune appears as track 5 of the album Second Sight. A live version appears as track 8 of the album Attack of the Killer V.

- ↑ "Rolling Coconut Review Japan Concert April 10 1977 | mockford". Mockford.wordpress.com. 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- 1 2

- ↑ Cincinnati Magazine - Jun 1986 - Page 73 " ... neither of which received much attention, Mack teamed up with an old friend named Ed Labunski to form a group called South "

- ↑ 1990 Lonnie Mack interview by Rikki Dee Hall.

- 1 2 "Michael Smith, "Gritz Speaks With Guitar Hero Lonnie Mack", June 2000". Swampland.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ SRV interview, Guitar World, November 1985, p. 30

- ↑ As heard on bootleg DVD entitled "American Caravan: Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble", recorded in 1986 at the Orpheum Theatre in Memphis

- ↑ Davis, Francis (2003-09-02). History of the Blues. Da Capo Press. p. 246. ISBN 0-306-81296-7.

- ↑ Video: Live at the Mocambo; Album: The Sky is Crying

- ↑ "Strike like Lightning". Youtube.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Album: SRV and Double Trouble: Box Set, Disc 2

- ↑ "...the Lonnie Mack-inspired instrumental". Blues.about.com. 1984-08-17. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Albums: SRV and Double Trouble: Box Set, Disc 2 and Live at Carnegie Hall; Vaughan said he "dedicated" the tune to Mack. Menn, Secrets From The Masters, Miller-Freeman, Inc, 1992, p. 278, ISBN 0-87930-260-7

- ↑ "Lonnie Mack Blues HDtrack downloads". HDtracks.com. 1999-12-04. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ CD, SRV: Solos, Sessions and Encores, track 7, Epic/Legacy, 2007

- ↑ "Further On Down The Road: Albert Collins, Lonnie Mack, Roy Buchanan Live at Carnegie Hall: Roy Buchanan musician, Lonnie Mack musician, Albert Collins musician: Movies & TV". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ↑ Guterman, Rolling Stone, December 1, 1988

- ↑ "G.E. Smith – Rock ‘N’ Roll Bash Artist Profile – Event: 2/22/14 « « Rock and Roll for Children Foundation Rock and Roll for Children Foundation". Rockandrollforchildren.org. 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ ""Live! - Attack of the Killer V" Review". Members.tripod.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Bo Baber (2000-05-31). "Review of Franktown Blues". Warehousecreek.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Photo of Mack playing at concert". Pureprairieleague.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑

- ↑ "Lonnie Mack sat in with my band Sat night...". The Gear Page. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ↑ "Lonnie Mack Comes Back To Life". Rockabillyhall.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Bobby Boyd profile at". Bobbyboydband.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Meiners, Larry [2001-03-01], Flying V: The Illustrated History of the Modernistic Guitar, Flying Vintage Publishing, p. 13.

- ↑ Larry Nager, Cincinnati Enquirer, "Lonnie Mack Wins Lifetime Achievement Cammy", March 15, 1998

- ↑ Commemorative plaque

- ↑ Please see "The Inductees" under category "Rock"

- ↑ Russ House, "Lonnie Mack Awarded Second Lifetime Achievement Award", March 15, 2002, Lonnie Mack 2nd Cammy Award

- ↑ "List of Hall of Famers". Rockabillyhall.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Full Inductee List". Widmarcs.com. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "The Guitar Collection". Theguitarcollectionbook.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

External links

- Lonnie Mack's official site

- Lonnie Mack biography at Allmusic website

- Rockabilly Hall of Fame website article on Mack

|