History of the Maldives

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of the Maldives | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-dynastic | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Dynastic ages | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Modern history | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Maldives portal | ||||||||||||||||||

| Outline of South Asian history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Riwatian people (1,900,000 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Soanian people (500,000 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stone Age (50,000–3000 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bronze Age (3000–1300 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iron Age (1200–230 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Classical period (230 BCE–1279CE) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late medieval period (1206–1596)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern period (1526–1858)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial period (1510–1961)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other states (1102–1947)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kingdoms of Sri Lanka

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nation histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Maldives is a nation consisting of 26 natural atolls, comprising 1192 islands.

Historical setting

Since very ancient times, the Maldives were ruled by kings (Radun) and occasionally queens (Ranin). Historically Maldives has had a strategic importance because of its location on the major marine routes of the Indian Ocean. Maldives' nearest neighbors are Sri Lanka and India, both of which have had cultural and economic ties with Maldives for centuries. The Maldives provided the main source of cowrie shells, then used as a currency throughout Asia and parts of the East African coast. Most probably Maldives were influenced by Kalingas of ancient India who were earliest sea traders to Sri Lanka and Maldives from India and were responsible for spread of Buddhism. Hence ancient Hindu culture has indelible impact on Maldives's local culture.

After the 16th century, when European colonial powers took over much of the trade in the Indian Ocean, first the Portuguese, and then the Dutch, and the French occasionally meddled with local politics. However, these interferences ended when the Maldive became a British Protectorate in the 19th century and the Maldivian monarchs were granted a good measure of self-governance.

Maldives gained total independence from the British on 26 July 1965.[1] However, they continued to maintain an air base on the island of Gan in the southernmost atoll until 1976. The British departure in 1976 at the height of the Cold War almost immediately triggered foreign speculation about the future of the air base. Apparently the Soviet Union made a move to request the use of the base, but the Maldives refused.

The greatest challenge facing the republic in the early 1990s was the need for rapid economic development and modernization, given the country's limited resource base in fishing, agriculture and tourism. Concern was also evident over a projected long-term rise in sea level, which would prove disastrous to the low-lying coral islands.

Early Age

Comparative studies of Maldivian oral, linguistic and cultural traditions and customs confirm that the first settlers were people from the southern shores of the neighbouring Indian subcontinent.[2]

These first Maldivians didn't leave any archaeological remains. Their buildings were probably built of wood, palm fronds and other perishable materials, which would have quickly decayed in the salt and wind of the tropical climate. Moreover, chiefs or headmen didn't reside in elaborate stone palaces, nor did their religion require the construction of large temples or compounds.[3]

The Buddhist Kingdom of Maldives

Despite being just mentioned briefly in most history books, the 1,400-year-long Buddhist period has a foundational importance in the history of the Maldives. It was during this period that the culture of the Maldives as we now know it both developed and flourished.[4]

Buddhism probably spread to the Maldives in the 3rd century BC, at the time of the Mauryan emperor Aśoka the Great, when it extended to the regions of Afghanistan and Central Asia, beyond the Mauryas' northwest border, as well as South to the island of Sri Lanka and the Maldive Islands. Serious studies of the archaeological remains of the Maldives began with the work of H. C. P. Bell, a British commissioner of the Ceylon Civil Service. Bell was shipwrecked on the islands in 1879 AD, and returned several times to investigate the ancient Buddhist ruins.

Early scholars like H.C.P. Bell, who resided in Sri Lanka most of his life, claim that Buddhism came to the Maldives from Sri Lanka. Since then, new archaeological discoveries point to Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist influences, which are likely to have come to the islands straight from the Subcontinent. An urn discovered in Maalhos (Ari Atoll) in the 1980s has a Vishvavajra inscribed with Protobengali script. This text was in the same script used in the ancient Buddhist centres of learning in Nalanda and Vikramashila. There is also a small Porites stupa in the Museum where the directional Dhyani Buddhas (Jinas) are etched in its four cardinal points as in the Mahayana tradition. Some coral blocks with fearsome heads of guardians are also displaying Vajrayana Iconography. All these relatively recent archaeological discoveries are today exhibited in a side room of the small National Museum in Male' along with other artifacts.

Buddhist remains have been also found in Minicoy Island, then part of the Maldive Kingdom, by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), in the latter half of the 20th century. Among these remains a Buddha head and stone foundations of a Vihara deserve special mention.

Following the Islamic concept that before Islam there was the time of Jahiliya (ignorance), in the history books used by Maldivians the introduction of Islam at the end of the 12th century is considered the cornerstone of the country's history. Islam remains the state religion in the 1990s. And yet the Maldivian language, the first Maldive scripts, the architecture, the ruling institutions, the customs and manners of the Maldivians originated at the time when the Maldives were a Buddhist Kingdom.

Buddhism became the dominant religion in the Maldives and enjoyed royal patronage for many centuries, probably as long as over one thousand and four hundred years. Practically all archaeological remains in the Maldives are from Buddhist stupas and monasteries, and all artifacts found to date display characteristic Buddhist iconography. Buddhist (and Hindu) temples were Mandala shaped, they are oriented according to the four cardinal points, the main gate being towards the east.Since building space and materials were scarce, Maldivians constructed their places of worship on the foundations of previous buildings.

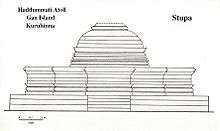

The ancient Buddhist stupas are called "havitta", "hatteli" or "ustubu" by the Maldivians according to the different atolls. These stupas and other archaeological remains, like foundations of Buddhist buildings Vihara, compound walls and stone baths, are found on many islands of the Maldives. They usually lie buried under mounds of sand and covered by vegetation. Local historian Hassan Ahmed Maniku counted as many as 59 islands with Buddhist archaeological sites in a provisional list he published in 1990. The largest monuments of the Buddhist era are in the islands fringing the eastern side of Haddhunmathi Atoll.

In the mid-1980s, the Maldivian government allowed the popular Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl, to excavate ancient sites. Despite the clear evidence that all the ancient ruins in Maldives are Buddhist, Heyerdahl claimed that early "sun-worshiping seafarers", called the "Redin", first settled on the islands. Keeping up with his sensationalist style, Heyerdahl argued that 'Redin' were people coming from somewhere else, whereas an ancient Maldivian poem (Fua Mulaku Rashoveshi) says: "Havitta uhe haudahau, Redin taneke hedi ihau". This poem gives us the clue about the name 'Redin'. According to Magieduruge Ibrahim Didi, a learned man from Fua Mulaku, it was merely the name which the converted Maldivians used to refer to their infidel (ghair dīn = 'redin') ancestors after the general conversion from Buddhism to Islam.

It is generally said that the conversion of the Maldives to Islam was peaceful, but historical evidence suggests the contrary. For example, the 12th century copperplates found at Isdhoo Island state that the monks (Sangumanun) from the monastery at that island were brought to Male' and beheaded.[5]

Unification and monarchy

Introduction of Islam

Inhabitants of the Middle east became interested in Maldives due to its strategic location and its abundant supply of cowrie shells. This was a form of currency that was widely used throughout Asia and parts of the East African coast since ancient times. Middle Eastern seafarers had just begun to take over the Indian Ocean trade routes in the 10th century and found Maldives to be an important link in those routes.

The importance of the Arabs as traders in the Indian Ocean by the 12th century may partly explain why the last Buddhist king of Maldives converted to Islam in the year 1153 (or 1193, for certain copper plate grants give a later date). The king thereupon adopted the Muslim title and name (in Arabic) of Sultan (besides the old Divehi title of Maha Radun or Ras Kilege or Rasgefānu) Muhammad al Adil, initiating a series of six Islamic dynasties consisting of eighty-four sultans and sultanas that lasted until 1932 when the sultanate became elective.

The person responsible for this conversion was a Sunni Muslim visitor named Abu al Barakat. His venerated tomb now stands on the grounds of Hukuru Mosque, or miski, in the capital of Malé. Built in 1656, this is the oldest mosque in Maldives. Arab interest in Maldives also was reflected in the residence there in the 1340s of the well-known North African traveler Ibn Battutah.

It is worth noticing that compared to the other areas of South Asia, the conversion of the Maldives to Islam happened relatively late. Arab Traders had converted populations in the Malabar Coast since the 7th century, and the Arab invader Muhammad Bin Qāsim had converted large swathes of Sindh to Islam at about the same time. The Maldives remained a Buddhist kingdom for another five hundred years (perhaps the south-westernmost Buddhist country) until the conversion to Islam.

The document known as Dhanbidhū Lōmāfānu gives information about the suppression of Buddhism in the southern Haddhunmathi Atoll, which had been a major center of that religion. Monks were taken to Male and beheaded, The Satihirutalu (the chattravali or chattrayashti crowning a stupa) were broken to disfigure the numerous stupasm and the statues of Vairocana, the transcendent Buddha of the middle world region, were destroyed.

Era of colonial powers

Portuguese

In 1558 the Portuguese established a small garrison with a Viador (Viyazoru), or overseer of a factory (trading post) in the Maldives, which they administered from their main colony in Goa. They tried to impose Christianity on the locals. Thus, fifteen years later, a local leader named Muhammad Thakurufaanu Al-Azam and his two brothers organized a popular revolt and drove the Portuguese out of Maldives. This event is now commemorated as National Day, and a small museum and memorial center honor the hero on his home island of Utheemu on North Thiladhummathi Atoll.

Dutch

In the mid-17th century, the Dutch, who had replaced the Portuguese as the dominant power in Ceylon, established hegemony over Maldivian affairs without involving themselves directly in local matters, which were governed according to centuries-old Islamic customs.

However, the British expelled the Dutch from Ceylon in 1796 and included Maldives as a British protected area. The status of Maldives as a British protectorate was officially recorded in an 1887 agreement in which the sultan accepted British influence over Maldivian external relations and defence. The British had no presence, however, on the leading island community of Malé. They left the islanders alone, as had the Dutch, with regard to internal administration to continue to be regulated by Muslim traditional institutions.

British

Britain got entangled with the Maldives as a result of domestic disturbances which targeted the settler community of Bora merchants who were British subjects in 1860's. Rivalry between two dominant families, the Athireege clan and the Kakaage clan was resolved with former winning the favour of the British authorities in Ceylon, who concluded a Protection Agreement in 1887. During the British era, which lasted until 1965, Maldives continued to be ruled under a succession of sultans. It was a period during which the Sultan's authority and powers were increasingly and decisively taken over by the Chief Minister, much to the chagrin of the British Governor-General who continued to deal with the ineffectual Sultan. Consequently, Britain encouraged the development of a constitutional monarchy, and the first Constitution was proclaimed in 1932. However, the new arrangements favoured neither the aging Sultan nor the wily Chief Minister, but rather a young crop of British-educated reformists. As a result, angry mobs were instigated against the Constitution which was publicly torn up.

The First Republic

Maldives remained a British crown protectorate until 1953 when the sultanate was suspended and the First Republic was declared under the short-lived presidency of Muhammad Amin Didi.

This first elected president of the country introduced several reforms. While serving as prime minister during the 1940s, Didi nationalized the fish export industry. As president he is remembered as a reformer of the education system and a promoter of women's rights. Muslim conservatives in Malé eventually ousted his government, and during a riot over food shortages, Didi was beaten by a mob and died on a nearby island.

Beginning in the 1950s, political history in Maldives was largely influenced by the British military presence in the islands. In 1954 the restoration of the sultanate perpetuated the rule of the past. Two years later, the United Kingdom obtained permission to reestablish its wartime airfield on Gan in the southernmost Addu Atoll. Maldives granted the British a 100-year lease on Gan that required them to pay £2,000 a year, as well as some 440,000 square metres on Hitaddu for radio installations.

In 1957, however, the new prime minister, Ibrahim Nasir, called for a review of the agreement in the interest of shortening the lease and increasing the annual payment. But Nasir, who was theoretically responsible to then sultan Muhammad Farid Didi, was challenged in 1959 by a local secessionist movement in the southern atolls that benefited economically from the British presence on Gan. This group cut ties with the Maldives government and formed an independent state with Abdullah Afif as president.

The short-lived state (1959–63), called the United Suvadive Republic, had a combined population of 20,000 inhabitants scattered in the southernmost atolls Huvadu, Addu and Fua Mulaku. In 1962 Nasir sent gunboats from Malé with government police on board to eliminate elements opposed to his rule. One year later the Suvadive republic was scrapped and Abdulla Afif went into exile to the Seychelles, where he died in 1993.

Meanwhile, in 1960 Maldives allowed the United Kingdom to continue to use both the Gan and the Hitaddu facilities for a thirty-year period, with the payment of £750,000 over the period of 1960 to 1965 for the purpose of Maldives' economic development.

Independence

On 26 July 1965, Maldives gained independence under an agreement signed with United Kingdom. The British government retained the use of the Gan and Hitaddu facilities. In a national referendum in March 1968, Maldivians abolished the sultanate and established a republic.

Nasir

The Second Republic was proclaimed in November 1968 under the presidency of Ibrahim Nasir, who had increasingly dominated the political scene. Under the new constitution, Nasir was elected indirectly to a four-year presidential term by the Majlis (legislature). He appointed Ahmed Zaki as the new prime minister.

In 1973 Nasir was elected to a second term under the constitution as amended in 1972, which extended the presidential term to five years and which also provided for the election of the prime minister by the Majlis. In March 1975, newly elected prime minister Zaki was arrested in a bloodless coup and was banished to a remote atoll. Observers suggested that Zaki was becoming too popular and hence posed a threat to the Nasir faction.

During the 1970s, the economic situation in Maldives suffered a setback when the Sri Lankan market for Maldives' main export of dried fish collapsed. Adding to the problems was the British decision in 1975 to close its airfield on Gan in line with its new policy of abandoning defense commitments east of the Suez Canal. A steep commercial decline followed the evacuation of Gan in March 1976. As a result, the popularity of Nasir's government suffered. Maldives's 20-year period of authoritarian rule under Nasir abruptly ended in 1978 when he fled to Singapore. A subsequent investigation revealed that he had absconded with millions of dollars from the state treasury. However, there has been no evidence so far and as a result it was believed that it was act of the new government to get their popularity and support among the civilians.

Gayoom

Elected to replace Nasir for a five-year presidential term in 1978 was Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, a former university lecturer and Maldivian ambassador to the United Nations (UN). The peaceful election was seen as ushering in a period of political stability and economic development in view of Gayoom's priority to develop the poorer islands. In 1978 Maldives joined the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Tourism also gained in importance to the local economy, reaching more than 120,000 visitors in 1985. The local populace appeared to benefit from increased tourism and the corresponding increase in foreign contacts involving various development projects.

Despite the popularity of Gayoom, those connected to the former President hired EX-SAS mercenaries in 1980 to carry out a coup to oust him. The attempt was sponsored by Ahmed Naseem, brother-in-law of Nasir and former junior Minister and was supported by a handful of Nasir loyalists. Naseem had objected to the emergence of Gayoom and had vowed to depose him within 6 months. Naseem's disaffection only increased when the parliament began investigating financial irregularities under Nasir as well as the murder of inmates and torture in Villingili Prison in the early 1970s, which implicated his brother-in-law, the erstwhile strongman Abdul Hannan Haleem who was Nasir's Ministers for Public Safety.

The small group of mercenaries arrived in the Maldives smuggling their light arms in diving equipment, but did not carry out the mission because Gayoom had been tipped about their arrival and they found that they had been misinformed about the popularity of Gayoom.

In 1983, a local shipping businessman, Reeko Ibrahim Maniku made a bid to win the parliamentary nomination by offering bribes to members of parliament and to High Court judges. Reeko Ibrahim remained in self-imposed exile, returning to Maldives only in 2006 and has since registered a political party, Social Democratic Party.

Despite coup attempts in 1980, 1983, and 1988, Gayoom served three more presidential terms. In the 1983, 1988, and 1993 elections, Gayoom received more than 90% of the vote. Although the government did not allow any legal opposition, Gayoom was opposed in the early 1990s by Islamists (also seen as fundamentalists) who wanted to impose a religious way of life and by some powerful local business leaders.

Whereas the 1980 and 1983 coup attempts against Gayoom's presidency were not considered serious, the third coup attempt in November 1988 alarmed the international community. About 80 armed Tamil mercenaries belonging to PLOTE landed on Malé before dawn aboard speedboats from a freighter. Disguised as visitors, a similar number had already infiltrated Malé earlier. Although the mercenaries quickly gained the nearby airport on Hulule, they failed to capture President Gayoom, who fled from house to house and asked for military intervention from India, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi immediately dispatched 1,600 troops by air to restore order in Malé. Less than 12 hours later, Indian paratroopers arrived on Hulele, causing some of the mercenaries to flee toward Sri Lanka in their freighter. Those unable to reach the ship in time were quickly rounded up. Nineteen people reportedly died in the fighting, and several taken hostage also died. Three days later an Indian frigate captured the mercenaries on their freighter near the Sri Lankan coast. In July 1989, a number of the mercenaries were returned to Maldives to stand trial. Gayoom commuted the death sentences passed against them to life imprisonment.

The 1988 coup had been masterminded and sponsored by a few disgruntled businessmen, chiefly Sikka Ahmed Ismail Maniku and Abdulla Luthufi, who were operating a farm in Sri Lanka. Earlier, the two of them had also been caught in an attempt to assassinate Nasir when he was president and had been tried and imprisoned before being released in 1975. The captured mercenaries and their paymasters were put on trial. Sikka Maniku and Luthufee were sentenced to death in 1989, but Gayoom commuted their sentences to life imprisonment. In 1994, Gayoom pardoned and released Sikka Maniku on humanitarian grounds as he had developed cardiovascular complications, and Maniku went into self-imposed exile in Colombo.

Ex-president Nasir denied any involvement in the coup. In fact, in July 1990, President Gayoom officially pardoned Nasir in absentia in recognition of his role in obtaining Maldives' independence.

Nasheed

Mohamed Nasheed Won Presidential election of 2008 held under the rules of new constitution. He controversially resigned from office after large number of police and army mutinied. Whether he resigned willingly or was forced to resign due to a bloodless coup is highly debated to this day.

Waheed

Mohammed Waheed Hassan Manik was sworn in as President of the Maldives on 7 February 2012, in connection to the resignation of President Nasheed amidst weeks of protests and demonstrations led by local police dissidents who opposed Nasheed’s 16 January order for the military to arrest Abdulla Mohamed, the Chief Justice of the Criminal Court.[6] Dr. Waheed opposed the arrest order and supported the opposition that forced Mohamed Nasheed to resign. A day later, Nasheed stated that he was forced to resign at gunpoint through a police mutiny and coup.[7][8] There have been allegations that Dr. Waheed was involved in planning the coup, though Dr. Waheed has denied involvement.[9]

See also

Sources and references

- ↑ Colliers Encyclopaedia (1989) Vol15 p276 McMillan Educational Company

- ↑ Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom

- ↑ Kalpana Ram, Mukkuvar Women. Macquarie University. 1993

- ↑ Clarence Maloney. People of the Maldive Islands. Orient Longman

- ↑ H.A. Maniku & G.D. Wijayawardhana. Isdhoo Loamaafaanu. Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka. Colombo 1986.

- ↑ http://www.haveeru.com.mv/news/39779

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/feb/09/maldives-president-forced-resign-gunpoint

- ↑ http://www.haveeru.com.mv/news/40135

- ↑ http://www.haveeru.com.mv/news/40839

- H.C.P. Bell, The Maldive Islands, An account of the physical features, History, Inhabitants, Productions and Trade. Colombo 1882, ISBN 81-206-1222-1

- Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom. Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5

- Divehi Tārīkhah Au Alikameh. Divehi Bahāi Tārikhah Khidmaiykurā Qaumī Markazu. Reprint 1958 edn. Male’ 1990.

- Skjølsvold, Arne. 1991. Archaeological Test-Excavations on the Maldive Islands. The Kon-Tiki Museum Occasional Papers, Vol. 2. Oslo.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.- WorldStatesmen

Further reading

- Tuckey (1815). "Maldiva Islands". Maritime Geography and Statistics. London.

- "Maldiva Islands". Parbury's Oriental Herald (London) 1. 1838.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of the Maldives. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||