Second Battle of Corinth

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

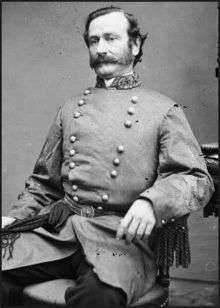

The Second Battle of Corinth (which, in the context of the American Civil War, is usually referred to as the Battle of Corinth, to differentiate it from the Siege of Corinth earlier the same year) was fought October 3–4, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi. For the second time in the Iuka-Corinth Campaign, Union Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans defeated a Confederate army, this time one under Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn.

After the Battle of Iuka, Maj. Gen. Sterling Price marched his army to meet with Van Dorn's. The combined force, under the command of the more senior Van Dorn, moved in the direction of Corinth, a critical rail junction in northern Mississippi, hoping to disrupt Union lines of communications and then sweep into Middle Tennessee. The fighting began on October 3 as the Confederates pushed the U.S. Army from the rifle pits originally constructed by the Confederates for the Siege of Corinth. The Confederates exploited a gap in the Union line and continued to press the Union troops until they fell back to an inner line of fortifications.

On the second day of battle, the Confederates moved forward to meet heavy Union artillery fire, storming Battery Powell and Battery Robinett, where desperate hand-to-hand fighting occurred. A brief incursion into the town of Corinth was repulsed. After a U.S. counterattack recaptured Battery Powell, Van Dorn ordered a general retreat. Rosecrans did not pursue immediately and the Confederates escaped destruction.

Background

As Confederate General Braxton Bragg moved north from Tennessee into Kentucky in September 1862, Union Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell pursued him from Nashville with his Army of the Ohio. Confederate forces under Van Dorn and Price in northern Mississippi were expected to advance into Middle Tennessee to support Bragg's effort, but the Confederates also needed to prevent Buell from being reinforced by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee. Since the conclusion of the Siege of Corinth that summer, Grant's army had been engaged in protecting supply lines in western Tennessee and northern Mississippi. At the Battle of Iuka on September 19, Maj. Gen. Sterling Price's Confederate Army of the West was defeated by forces under Grant's overall command, but tactically under Rosecrans, the commander of the Army of the Mississippi. (Grant's second column approaching Iuka, commanded by Maj. Gen. Edward Ord, did not participate in the battle as planned. An acoustic shadow apparently prevented Grant and Ord from hearing the sounds of the battle starting.) Price had hoped to combine his small army with Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn's Army of West Tennessee and disrupt Grant's communications, but Rosecrans struck first, causing Price to retreat from Iuka. Rosecrans's pursuit of Price was ineffectual.[3]

After Iuka, Grant established his headquarters at Jackson, Tennessee, a central location to communicate with his commands at Corinth and Memphis. Rosecrans returned to Corinth. Ord's three divisions of Grant's Army of the Tennessee moved to Bolivar, Tennessee, northwest of Corinth, to join with Maj. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut. Thus, Grant's forces in the immediate vicinity consisted of 12,000 men at Bolivar, Rosecrans's 23,000 at Corinth, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's 7,000 at Memphis, and another 6,000 as a general reserve at Jackson.[4]

Price's army marched to Ripley where it joined Van Dorn on September 28. Van Dorn was the senior officer and took command of the combined force, numbering about 22,000 men. They marched on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad to Pocahontas, Tennessee, on October 1. From this point they had a number of opportunities for further moves and Grant was uncertain about their intentions. When they bivouacked on October 2 at Chewalla, Grant became certain that Corinth was the target. The Confederates hoped to seize Corinth from an unexpected direction, isolating Rosecrans from reinforcements, and then sweep into Middle Tennessee. Grant sent word to Rosecrans to be prepared for an attack, at the same time directing Hurlbut to keep an eye on the enemy and strike him on the flank if a favorable opportunity offered. Despite the warning from Grant, Rosecrans was not convinced that Corinth was necessarily the target of Van Dorn's advance. He believed that the Confederate commander would not be foolhardy enough to attack the fortified town and might well instead choose to strike the Mobile and Ohio railroad and maneuver the U.S. soldiers out of their position.[5]

Along the north and east sides of Corinth, about two miles from the town, was a line of entrenchments, extending from the Chewalla Road on the northwest to the Mobile and Ohio Railroad on the south, that had been constructed by Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard's army before it evacuated the town in May. These lines were too extensive for Rosecrans's 23,000 men to defend, so with the approval of Grant, Rosecrans modified the lines to emphasize the defense of the town and the ammunition magazines near the junction of the two railroads. The inner line of redoubts, closer to the town, called the Halleck Line, was much more substantial. A number of formidable named batteries, guns positioned in strong earthwork defenses, were part of the inner line: Batteries Robinett, Williams, Phillips, Tannrath, and Lothrop, in the area known as College Hill.[6] They were connected by breastworks, and during the last four days of September these works had been strengthened, and the trees in the vicinity of the centrally placed Battery Robinett had been felled to form an abatis. Rosecrans's plan was to absorb the expected Confederate advance with a skirmish line at the old Confederate entrenchments and to then meet the bulk of the Confederate attack with his main force along the Halleck Line, about a mile from the center of town. His final stand would be made around the batteries on College Hill. His men were provided with three days' rations and 100 rounds of ammunition. Van Dorn was not aware of the strength of his opponent, who had prudently called in two reinforcing divisions from the Army of the Tennessee to deal with the difficulty of assaulting these prepared positions.[7]

Opposing forces

| Principal Union commanders |

|---|

|

| Principal Confederate commanders |

|

Union

Rosecrans's Army of the Mississippi was organized as follows:[8]

- Division of Brig. Gen. David S. Stanley included the brigades of Cols. John W. Fuller and Joseph A. Mower.

- Division of Brig. Gen. Charles S. Hamilton included the brigades of Brig. Gens. Napoleon B. Buford and Jeremiah C. Sullivan.

- Cavalry division of Col. John K. Mizner included the brigades of Cols. Edward Hatch and Albert L. Lee.

- A division on loan from the Army of the Tennessee, commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas A. Davies, included the brigades of Brig. Gens. Pleasant A. Hackleman and Richard J. Oglesby, and Col. Silas D. Baldwin.

- A second division on loan, commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas J. McKean, included the brigades of Brig. Gen. John McArthur and Cols. John M. Oliver and Marcellus M. Crocker.

Confederate

Van Dorn's combined Confederate Army of West Tennessee[9] was organized as follows:[10]

- Price's Corps, also known as the Army of the West, with two divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. Louis Hébert (brigades of Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green and Colonels Elijah Gates, W. Bruce Colbert, and John D. Martin) and Brig. Gen. Dabney H. Maury (brigades of Brig. Gens. John C. Moore and William L. Cabell, and Col. Charles W. Phifer).

- The 1st Division of the District of the Mississippi, commanded by Maj. Gen. Mansfield Lovell, with the brigades of Brig. Gens. Albert Rust, John B. Villepigue, John S. Bowen, and a cavalry brigade commanded by Col. William H. Jackson, and Major St. L. Dupiere's Louisiana Zouave battalion.

Battle

October 3

On the morning of October 3, three of Rosecrans's divisions advanced into the old Confederate rifle pits north and northwest of town: McKean on the left, Davies in the center, and Hamilton on the right. Stanley's division was held in reserve south of town. Van Dorn began his assault at 10 a.m. with Lovell's division attacking McArthur's brigade (McKean's division, on the Union left) from three sides. Van Dorn's plan was a double envelopment, in which Lovell would open the fight, in the hope that Rosecrans would weaken his right to reinforce McKean, at which time Price would make the main assault against the U.S. right and enter the works. Lovell made a determined attack on Oliver and as soon as he became engaged Maury opened the fight with Davies's left. McArthur quickly moved four regiments to Oliver's support and at the same time Davies advanced his line to the entrenchments. These movements left a gap between Davies and McKean, through which the Confederates forced their way about 1:30 p.m., and the whole Union line fell back to within half a mile of the redoubts, leaving two pieces of artillery in the hands of the Confederates.[11]

During this part of the action Gen. Hackleman was killed and Gen. Oglesby (the future governor of Illinois) seriously wounded, shot through the lungs. About 3 p.m. Hamilton was ordered to change front and attack the Confederates on the left flank, but through a misunderstanding of the order and the unmasking of a force on Buford's front, so much time was lost that it was sunset before the division was in position for the movement, and it had to be abandoned. Van Dorn in his report says: "One hour more of daylight and victory would have soothed our grief for the loss of the gallant dead who sleep on that lost but not dishonored field." But one hour more of daylight would have hurled Hamilton's as-yet unengaged brigades on the Confederate's left and rear, which would in all probability have driven Van Dorn from the field and made the second day's battle unnecessary.[12]

So far the advantage had been with the Confederates. Rosecrans had been driven back at all points, and night found his entire army except pickets inside the redoubts. Both sides had been exhausted from the fighting. The weather had been hot (high of 94 °F) and water was scarce, causing many men to nearly faint from their exertions. During the night the Confederates slept within 600 yards of the Union works, and Van Dorn readjusted his lines for the attack the next day. He abandoned his sophisticated plans for double envelopments. Shelby Foote wrote, "His blood was up; it was Rosecrans he was after, and he was after him in the harshest, most straightforward way imaginable. Today he would depend not on deception to complete the destruction begun the day before, but on the rapid point-blank fire of his guns and the naked valor of his infantry."[13]

Rosecrans's biographer, William M. Lamers, reported that Rosecrans was confident at the end of the first day of battle, saying "We've got them where we want them" and that some of the general's associates claimed that he was in "magnificent humor." Peter Cozzens, however, suggested that Rosecrans was "tired and bewildered, certain only he was badly outnumbered—at least three to one by his reckoning."[14] Army of the Tennessee historian Steven E. Woodworth portrayed Rosecrans's conduct in a negative light:

Rosecrans ... had not done well. He had failed to anticipate the enemy's action, put little more than half his troops into the battle, and called on his men to fight on ground they could not possibly hold. He had sent a series of confusing and unrealistic orders to his division commanders and had done nothing to coordinate their activities, while he personally remained safely back in Corinth. The movements of the army that day had had nothing to do with any plan of his to develop the enemy or make a fighting withdrawal. The troops and their officers had simply held on as best as they could.[15]

October 4

At 4:30 a.m. on October 4, the Confederates opened up on the Union inner line of entrenchments with a six-gun battery, which kept up its bombardment until after sunrise. When the guns fell silent, the U.S. troops prepared themselves to resist an attack. But the attack was slow in coming. Van Dorn had directed Hébert to begin the engagement at daylight, and the artillery fire was merely preliminary to enable Hébert to get into position for the assault.[16]

At 7 a.m., Hébert sent word to Van Dorn that he was too ill to lead his division, and Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green was ordered to assume command and advance at once. Nearly two hours more elapsed before Green moved to the attack, with four brigades in echelon, until he occupied a position in the woods north of town. There he formed in line, facing south, and made a charge on Battery Powell with the brigades of Gates and McLain (replacing Martin), while the brigades of Moore (replacing Green) and Colbert attacked Hamilton's line. The assault on the battery was successful, capturing the guns and scattering the troops from Illinois and Iowa. Hamilton repulsed the attack on his position and then sent a portion of his command to the assistance of Davies, who rallied his men, drove the Confederates out of the battery, and recaptured the guns.[18]

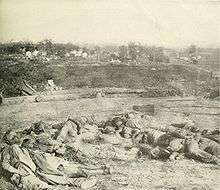

Maury had been engaged sometime before this. As soon as he heard the firing on his left, he knew that Davies and Hamilton would be kept too busy to interfere with his movements, and gave the order for his division to move straight toward the town. His right encountered a stubborn resistance at about 11 a.m. from Battery Robinett, a redan protected by a five-foot ditch, sporting three 20-pounder Parrott rifles commanded by Lt. Henry Robinett. Fierce hand-to-hand combat ensued, and Maury was forced to retire with heavy losses from arguably the hottest action of the two-day battle. Col. William P. Rogers of the 2nd Texas, a Mexican–American War comrade of President Jefferson Davis, was among those killed in the charge. Col. Lawrence Sullivan Ross of the 6th Texas was thrown from his horse and mistakenly reported killed with Rogers.[19]

Phifer's brigade on the left met with better success, driving back Davies's left flank and entering the town. But their triumph was short-lived, as part of Sullivan's brigade, held as a reserve on Hamilton's left, charged on the Confederates, who were thrown into confusion in the narrow streets, and as they fell back came within range of batteries on both flanks of the Union army, the cross-fire utterly routing them. Cabell's brigade of Maury's division was sent to reinforce the troops that had captured Battery Powell, but before it arrived, Davies and Hamilton had recaptured it, and as Cabell advanced against it, he was met by a murderous fire that caused his men to retreat.[20]

Meanwhile, Lovell had been skirmishing with the Union left in the vicinity of Battery Phillips, in preparation for a general advance. Before his arrangements were complete he was ordered to send a brigade to Maury's assistance, and soon afterward received orders to place his command so as to cover the retreat of the army. At 4 p.m., reinforcements from Grant under the command of Brig. Gen. James B. McPherson arrived from Jackson. But the battle of Corinth had effectively been over since 1 p.m. and the Confederates were in full retreat.[21]

Aftermath

It lives in the memory of every soldier who fought that day how his General plunged into the thickest of the conflict, fought like a private soldier, dealt sturdy blows with the flat of his sword on the runaways, and fairly drove them to stand. Then came a quick rally which his magnificent bearing inspired, a storm of grape from the batteries tore its way through the Rebel ranks, reinforcements which Rosecrans sent flying gave impetus to the National advance, and the charging column was speedily swept back outside the entrenchments.

Rosecrans's army lost 2,520 (355 killed, 1,841 wounded, and 324 missing) at Corinth; Van Dorn's losses were 4,233 (473 killed, 1,997 wounded, and 1,763 captured or missing).[2]

Once again, Rosecrans's performance during the second day of the battle has been the subject of dispute among historians. His biographer, Lamers, paints a romantic picture:

One of Davies' men, David Henderson, watched Rosecrans as he dashed in front of the Union lines. Bullets carried his hat away. His hair flew in the wind. As he rode along he shouted: "Soldiers! Stand by your country." "He was the only general I ever knew," Henderson said later, "who was closer to the enemy than we were who fought at the front." Henderson (after the war, a Congressman from Iowa and Speaker of the House of Representatives) wrote that Rosecrans was the "Central leading and victorious spirit. ... By his splendid example in the thickest of the fight he succeeded in restoring the line before it was completely demoralized; and the men, brave when bravely led, fought again."[23]

Peter Cozzens, author of a recent book-length study of Iuka and Corinth, came to the opposite conclusion:

Rosecrans was in the thick of battle, but his presence was hardly inspiring. The Ohioan had lost all control of his infamous temper, and he cursed as cowards everyone who pushed past him until he, too lost hope. ... Rosecrans's histrionics nearly cost him his life. "On the second day I was everywhere on the line of battle," he wrote with disingenuous pride. "Temple Clark of my staff was shot through the breast. My saber-tache strap was caught by a bullet, and my gloves were stained with the blood of a staff officer wounded at my side. An alarm spread that I was killed, but it was soon stopped by my appearance on the field."[24]

Rosecrans's performance immediately after the battle was lackluster. Grant had given him specific orders to pursue Van Dorn without delay, but he did not begin his march until the morning of October 5, explaining that his troops needed rest and the thicketed country made progress difficult by day and impossible by night. At 1 p.m. on October 4, when pursuit would have been most effective, Rosecrans rode along his line to deny in person a rumor that he had been slain. At Battery Robinett he dismounted, bared his head, and told his soldiers, "I stand in the presence of brave men, and I take my hat off to you."[25]

Grant wrote disgustedly, "Two or three hours of pursuit on the day of the battle without anything except what the men carried on their persons, would have been worth more than any pursuit commenced the next day could have possibly been."[26] Rosecrans returned to Corinth to find that he was a hero in the Northern press. He was soon ordered to Cincinnati, where he was given command of the Army of the Ohio (soon to be renamed the Army of the Cumberland), replacing Don Carlos Buell, who had similarly failed to pursue retreating Confederates from the Battle of Perryville.[27]

Although his army had been badly mauled, Van Dorn escaped completely, evading Union troops sent by Grant later on October 5 at the Battle of Hatchie's Bridge, and marching to Holly Springs, Mississippi. He attributed his defeat to the failure of Hébert to open the second-day engagement on time, but nevertheless he was replaced by Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton immediately after the battle. There were widespread outcries of indignation throughout the South over the senseless casualties at Corinth. Van Dorn requested a court of inquiry to answer charges that he had been drunk on duty at Corinth and that he had neglected his wounded on the retreat. The court cleared him of all blame by unanimous decision.[28]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Eicher, p. 374; Kennedy, p. 130. Woodworth, p. 225, and Lamers, p. 133, list Rosecrans's strength as four divisions of 18,000 men.

- 1 2 3 Eicher, p. 378. Woodworth, p. 235, reports Confederate casualties as "nearly 4,000." Kennedy, p. 131, cites Confederate losses of 4,800, Union 2,350.

- ↑ Korn, pp. 34–37; Kennedy, p. 129; Welcher, pp. 553–59; Woodworth, pp. 217–24; Eicher, p. 374.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 374; Cozzens, p. 144.

- ↑ Lamers, pp. 133–35.

- ↑ The Corinth website describes Corona College, "established in 1857 by the Rev. L. B. Gaston, was an elegant girls school. It was used as a hospital during 1862–1864 by Confederate and later Union Armies. In January 1864, it was burned when Federal forces abandoned Corinth." Cozzens, p. 22, refers to Corona Female College. "Boosters lauded the college, which stood on a knoll southwest of the railway junction, as 'a magnificent building surrounded by a lofty dome.'"

- ↑ Cozzens, pp. 145–46; Welcher, p. 554; Kennedy, p. 131.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 375; Welcher, pp. 558–59; Cozzens, pp. 326–27.

- ↑ Van Dorn's army had the same name as Ulysses S. Grant's at the time. The Union army of that name was renamed the Army of the Tennessee on October 16, 1862, although historians usually refer to the latter name for most actions in 1862. See Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3, pp. 892, 856–57.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 375; Cozzens, pp. 327–28.

- ↑ Woodworth, pp. 226–28; Cozzens, pp. 160–74; Eicher, pp. 375–77; Korn, p. 40; Kennedy, p. 131.

- ↑ Lamers, pp. 138, 141; Cozzens, pp. 198–220; Eicher, pp. 377; Korn, p. 40.

- ↑ Foote, p. 723.

- ↑ Lamers, pp. 141–42; Cozzens, p. 224.

- ↑ Woodworth, p. 229.

- ↑ Cozzens, pp. 233–35; Welcher, p. 556; Woodworth, pp. 229–30; Lamers, p. 146.

- ↑ Cozzens, p. 255. Eicher, p. 278, states that is one of only a very few Civil War photographs that show an important officer deceased on the field. It is sometimes erroneously reported that Rogers's second-in-command, Col. Lawrence Sullivan Ross, lies beside him. In fact, Ross went on to become a general and later the governor of Texas. He died in 1898.

- ↑ Cozzens, pp. 235–36, 243–50; Welcher, p. 556; Lamers, pp. 148–50.

- ↑ Welcher, pp. 556–57; Cozzens, pp. 253–63, 267; Woodworth, p. 233; Kennedy, p. 131; Korn, p. 41; Eicher, pp. 377–78; Lamers, pp. 151–54.

- ↑ Lamers, pp. 148–49; Cozzens, pp. 267–70; Welcher, p. 557.

- ↑ Lamers, p. 152; Cozzens, p. 276; Welcher, p. 557.

- ↑ Reid, vol. I, p. 325.

- ↑ Lamers, p. 149.

- ↑ Cozzens, pp. 251–52.

- ↑ Foote, p. 725.

- ↑ Nevins, p. 374.

- ↑ Lamers, pp. 181–82.

- ↑ Korn, p. 44; Welcher, pp. 557–58.

References

- Cozzens, Peter. The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8078-2320-1.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 1, Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0-394-49517-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Korn, Jerry, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. War on the Mississippi: Grant's Vicksburg Campaign. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4744-4.

- Lamers, William M. The Edge of Glory: A Biography of General William S. Rosecrans, U.S.A. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1961. ISBN 0-8071-2396-X.

- Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union. Vol. 2, War Becomes Revolution 1862 – 1863. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1960. ISBN 1-56852-297-5.

- Reid, Whitelaw. Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers. Vol. 1, The History of the State during the War, and the Lives of Her Generals. Cincinnati, OH: Moore, Wilstach, and Baldwin, 1868.

- Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 2, The Western Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-253-36454-X.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 0-375-41218-2.

- The Union Army; A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861–65 — Records of the Regiments in the Union Army — Cyclopedia of Battles — Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers. Vol. 6. Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1997. First published 1908 by Federal Publishing Company.

- National Park Service battle description

Further reading

- Ballard, Michael B. Civil War Mississippi: A Guide. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2000. ISBN 1-57806-196-2.

- Carter, Arthur B. The Tarnished Cavalier: Major General Earl Van Dorn, C.S.A. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1999. ISBN 1-57233-047-3.

- Castel, Albert (1993) [1st pub. 1968]. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West (Louisiana pbk. ed.). Baton Rouge; London: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1854-0. LCCN 68-21804.

- Dossman, Steven Nathaniel. Campaign for Corinth: Blood in Mississippi. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 2006. ISBN 1-893114-51-1.

External links

- Second Battle of Corinth: Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- National Park Service interpretive center for Corinth (part of the Shiloh National Military Park)

- Corinth, Mississippi, website

- The Siege and Battle of Corinth: A New Kind of War, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Callaway Confederate Letter:Confederate soldier's letter detailing the battle

Coordinates: 34°56′26″N 88°31′50″W / 34.9406°N 88.5306°W