Scientific method

The scientific method is a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge.[2] To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry is commonly based on empirical or measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning.[3] The Oxford English Dictionary defines the scientific method as "a method or procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses."[4]

The scientific method is an ongoing process, which usually begins with observations about the natural world. Human beings are naturally inquisitive, so they often come up with questions about things they see or hear and often develop ideas (hypotheses) about why things are the way they are. The best hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested in various ways, including making further observations about nature. In general, the strongest tests of hypotheses come from carefully controlled and replicated experiments that gather empirical data. Depending on how well the tests match the predictions, the original hypothesis may require refinement, alteration, expansion or even rejection. If a particular hypothesis becomes very well supported a general theory may be developed.[1]

Although procedures vary from one field of inquiry to another, identifiable features are frequently shared in common between them. The overall process of the scientific method involves making conjectures (hypotheses), deriving predictions from them as logical consequences, and then carrying out experiments based on those predictions.[5][6] A hypothesis is a conjecture, based on knowledge obtained while formulating the question. The hypothesis might be very specific or it might be broad. Scientists then test hypotheses by conducting experiments. Under modern interpretations, a scientific hypothesis must be falsifiable, implying that it is possible to identify a possible outcome of an experiment that conflicts with predictions deduced from the hypothesis; otherwise, the hypothesis cannot be meaningfully tested.[7]

The purpose of an experiment is to determine whether observations agree with or conflict with the predictions derived from a hypothesis.[8] Experiments can take place in a college lab, on a kitchen table, at CERN's Large Hadron Collider, at the bottom of an ocean, on Mars, and so on. There are difficulties in a formulaic statement of method, however. Though the scientific method is often presented as a fixed sequence of steps, it represents rather a set of general principles.[9] Not all steps take place in every scientific inquiry (or to the same degree), and are not always in the same order.[10]

Overview

- The DNA example below is a synopsis of this method

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), 965–1039 Iraq. A polymath, considered by some to be the father of modern scientific methodology, due to his emphasis on experimental data and reproducibility of its results.[11][12] |

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630). "Kepler shows his keen logical sense in detailing the whole process by which he finally arrived at the true orbit. This is the greatest piece of Retroductive reasoning ever performed." – C. S. Peirce, c. 1896, on Kepler's reasoning through explanatory hypotheses[13] |

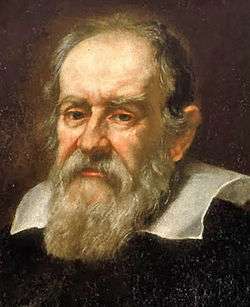

According to Morris Kline,[14] "Modern science owes its present flourishing state to a new scientific method which was fashioned almost entirely by Galileo Galilei" (1564−1642). Dudley Shapere[15] takes a more measured view of Galileo's contribution. |

The scientific method is the process by which science is carried out.[16] As in other areas of inquiry, science (through the scientific method) can build on previous knowledge and develop a more sophisticated understanding of its topics of study over time.[17][18][19][20][21][22] This model can be seen to underlay the scientific revolution.[23] One thousand years ago, Alhazen argued the importance of forming questions and subsequently testing them,[24] an approach which was advocated by Galileo in 1638 with the publication of Two New Sciences.[25] The current method is based on a hypothetico-deductive model[26] formulated in the 20th century, although it has undergone significant revision since first proposed (for a more formal discussion, see below).

Process

The overall process involves making conjectures (hypotheses), deriving predictions from them as logical consequences, and then carrying out experiments based on those predictions to determine whether the original conjecture was correct.[5] There are difficulties in a formulaic statement of method, however. Though the scientific method is often presented as a fixed sequence of steps, they are better considered as general principles.[27] Not all steps take place in every scientific inquiry (or to the same degree), and are not always in the same order. As noted by William Whewell (1794–1866), "invention, sagacity, [and] genius"[10] are required at every step.

Formulation of a question

The question can refer to the explanation of a specific observation, as in "Why is the sky blue?", but can also be open-ended, as in "How can I design a drug to cure this particular disease?" This stage frequently involves looking up and evaluating evidence from previous experiments, personal scientific observations or assertions, and/or the work of other scientists. If the answer is already known, a different question that builds on the previous evidence can be posed. When applying the scientific method to scientific research, determining a good question can be very difficult and affects the final outcome of the investigation.[28]

Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a conjecture, based on knowledge obtained while formulating the question, that may explain the observed behavior of a part of our universe. The hypothesis might be very specific, e.g., Einstein's equivalence principle or Francis Crick's "DNA makes RNA makes protein",[29] or it might be broad, e.g., unknown species of life dwell in the unexplored depths of the oceans. A statistical hypothesis is a conjecture about some population. For example, the population might be people with a particular disease. The conjecture might be that a new drug will cure the disease in some of those people. Terms commonly associated with statistical hypotheses are null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis. A null hypothesis is the conjecture that the statistical hypothesis is false, e.g., that the new drug does nothing and that any cures are due to chance effects. Researchers normally want to show that the null hypothesis is false. The alternative hypothesis is the desired outcome, e.g., that the drug does better than chance. A final point: a scientific hypothesis must be falsifiable, meaning that one can identify a possible outcome of an experiment that conflicts with predictions deduced from the hypothesis; otherwise, it cannot be meaningfully tested.

Prediction

This step involves determining the logical consequences of the hypothesis. One or more predictions are then selected for further testing. The more unlikely that a prediction would be correct simply by coincidence, then the more convincing it would be if the prediction were fulfilled; evidence is also stronger if the answer to the prediction is not already known, due to the effects of hindsight bias (see also postdiction). Ideally, the prediction must also distinguish the hypothesis from likely alternatives; if two hypotheses make the same prediction, observing the prediction to be correct is not evidence for either one over the other. (These statements about the relative strength of evidence can be mathematically derived using Bayes' Theorem).[30]

Testing

This is an investigation of whether the real world behaves as predicted by the hypothesis. Scientists (and other people) test hypotheses by conducting experiments. The purpose of an experiment is to determine whether observations of the real world agree with or conflict with the predictions derived from a hypothesis. If they agree, confidence in the hypothesis increases; otherwise, it decreases. Agreement does not assure that the hypothesis is true; future experiments may reveal problems. Karl Popper advised scientists to try to falsify hypotheses, i.e., to search for and test those experiments that seem most doubtful. Large numbers of successful confirmations are not convincing if they arise from experiments that avoid risk.[8] Experiments should be designed to minimize possible errors, especially through the use of appropriate scientific controls. For example, tests of medical treatments are commonly run as double-blind tests. Test personnel, who might unwittingly reveal to test subjects which samples are the desired test drugs and which are placebos, are kept ignorant of which are which. Such hints can bias the responses of the test subjects. Furthermore, failure of an experiment does not necessarily mean the hypothesis is false. Experiments always depend on several hypotheses, e.g., that the test equipment is working properly, and a failure may be a failure of one of the auxiliary hypotheses. (See the Duhem–Quine thesis.) Experiments can be conducted in a college lab, on a kitchen table, at CERN's Large Hadron Collider, at the bottom of an ocean, on Mars (using one of the working rovers), and so on. Astronomers do experiments, searching for planets around distant stars. Finally, most individual experiments address highly specific topics for reasons of practicality. As a result, evidence about broader topics is usually accumulated gradually.

Analysis

This involves determining what the results of the experiment show and deciding on the next actions to take. The predictions of the hypothesis are compared to those of the null hypothesis, to determine which is better able to explain the data. In cases where an experiment is repeated many times, a statistical analysis such as a chi-squared test may be required. If the evidence has falsified the hypothesis, a new hypothesis is required; if the experiment supports the hypothesis but the evidence is not strong enough for high confidence, other predictions from the hypothesis must be tested. Once a hypothesis is strongly supported by evidence, a new question can be asked to provide further insight on the same topic. Evidence from other scientists and experience are frequently incorporated at any stage in the process. Depending on the complexity of the experiment, many iterations may be required to gather sufficient evidence to answer a question with confidence, or to build up many answers to highly specific questions in order to answer a single broader question.

DNA example

The basic elements of the scientific method are illustrated by the following example from the discovery of the structure of DNA:

|

The discovery became the starting point for many further studies involving the genetic material, such as the field of molecular genetics, and it was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962. Each step of the example is examined in more detail later in the article.

Other components

The scientific method also includes other components required even when all the iterations of the steps above have been completed:[39]

Replication

If an experiment cannot be repeated to produce the same results, this implies that the original results might have been in error. As a result, it is common for a single experiment to be performed multiple times, especially when there are uncontrolled variables or other indications of experimental error. For significant or surprising results, other scientists may also attempt to replicate the results for themselves, especially if those results would be important to their own work.[40]

External review

The process of peer review involves evaluation of the experiment by experts, who typically give their opinions anonymously. Some journals request that the experimenter provide lists of possible peer reviewers, especially if the field is highly specialized. Peer review does not certify correctness of the results, only that, in the opinion of the reviewer, the experiments themselves were sound (based on the description supplied by the experimenter). If the work passes peer review, which occasionally may require new experiments requested by the reviewers, it will be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. The specific journal that publishes the results indicates the perceived quality of the work.[41]

Data recording and sharing

Scientists typically are careful in recording their data, a requirement promoted by Ludwik Fleck (1896–1961) and others.[42] Though not typically required, they might be requested to supply this data to other scientists who wish to replicate their original results (or parts of their original results), extending to the sharing of any experimental samples that may be difficult to obtain.[43]

Scientific inquiry

Scientific inquiry generally aims to obtain knowledge in the form of testable explanations that can be used to predict the results of future experiments. This allows scientists to gain a better understanding of the topic being studied, and later be able to use that understanding to intervene in its causal mechanisms (such as to cure disease). The better an explanation is at making predictions, the more useful it frequently can be, and the more likely it is to continue explaining a body of evidence better than its alternatives. The most successful explanations, which explain and make accurate predictions in a wide range of circumstances, are often called scientific theories.

Most experimental results do not produce large changes in human understanding; improvements in theoretical scientific understanding is typically the result of a gradual process of development over time, sometimes across different domains of science.[44] Scientific models vary in the extent to which they have been experimentally tested and for how long, and in their acceptance in the scientific community. In general, explanations become accepted over time as evidence accumulates on a given topic, and the explanation in question is more powerful than its alternatives at explaining the evidence. Often the explanations are altered over time, or explanations are combined to produce new explanations.

Properties of scientific inquiry

Scientific knowledge is closely tied to empirical findings, and can remain subject to falsification if new experimental observation incompatible with it is found. That is, no theory can ever be considered final, since new problematic evidence might be discovered. If such evidence is found, a new theory may be proposed, or (more commonly) it is found that modifications to the previous theory are sufficient to explain the new evidence. The strength of a theory can be argued to be related to how long it has persisted without major alteration to its core principles.

Theories can also subject to subsumption by other theories. For example, thousands of years of scientific observations of the planets were explained almost perfectly by Newton's laws. However, these laws were then determined to be special cases of a more general theory (relativity), which explained both the (previously unexplained) exceptions to Newton's laws and predicting and explaining other observations such as the deflection of light by gravity. Thus, in certain cases independent, unconnected, scientific observations can be connected to each other, unified by principles of increasing explanatory power.[45]

Since new theories might be more comprehensive than what preceded them, and thus be able to explain more than previous ones, successor theories might be able to meet a higher standard by explaining a larger body of observations than their predecessors.[45] For example, the theory of evolution explains the diversity of life on Earth, how species adapt to their environments, and many other patterns observed in the natural world;[46][47] its most recent major modification was unification with genetics to form the modern evolutionary synthesis. In subsequent modifications, it has also subsumed aspects of many other fields such as biochemistry and molecular biology.

Beliefs and biases

Scientific methodology often directs that hypotheses be tested in controlled conditions wherever possible. This is frequently possible in certain areas, such as in the biological sciences, and more difficult in other areas, such as in astronomy. The practice of experimental control and reproducibility can have the effect of diminishing the potentially harmful effects of circumstance, and to a degree, personal bias. For example, pre-existing beliefs can alter the interpretation of results, as in confirmation bias; this is a heuristic that leads a person with a particular belief to see things as reinforcing their belief, even if another observer might disagree (in other words, people tend to observe what they expect to observe).

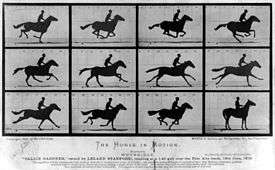

A historical example is the belief that the legs of a galloping horse are splayed at the point when none of the horse's legs touches the ground, to the point of this image being included in paintings by its supporters. However, the first stop-action pictures of a horse's gallop by Eadweard Muybridge showed this to be false, and that the legs are instead gathered together.[48] Another important human bias that plays a role is a preference for new, surprising statements (see appeal to novelty), which can result in a search for evidence that the new is true.[2] In contrast to this standard in the scientific method, poorly attested beliefs can be believed and acted upon via a less rigorous heuristic,[49] sometimes taking advantage of the narrative fallacy that when narrative is constructed its elements become easier to believe.[50][51] Sometimes, these have their elements assumed a priori, or contain some other logical or methodological flaw in the process that ultimately produced them.[52]

Elements of the scientific method

There are different ways of outlining the basic method used for scientific inquiry. The scientific community and philosophers of science generally agree on the following classification of method components. These methodological elements and organization of procedures tend to be more characteristic of natural sciences than social sciences. Nonetheless, the cycle of formulating hypotheses, testing and analyzing the results, and formulating new hypotheses, will resemble the cycle described below.

- Four essential elements[53][54][55] of the scientific method[56] are iterations,[57][58] recursions,[59] interleavings, or orderings of the following:

- Characterizations (observations,[60] definitions, and measurements of the subject of inquiry)

- Hypotheses[61][62] (theoretical, hypothetical explanations of observations and measurements of the subject)[63]

- Predictions (reasoning including deductive reasoning[64] from the hypothesis or theory)

- Experiments[65] (tests of all of the above)

Each element of the scientific method is subject to peer review for possible mistakes. These activities do not describe all that scientists do (see below) but apply mostly to experimental sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology). The elements above are often taught in the educational system as "the scientific method".[66]

The scientific method is not a single recipe: it requires intelligence, imagination, and creativity.[67] In this sense, it is not a mindless set of standards and procedures to follow, but is rather an ongoing cycle, constantly developing more useful, accurate and comprehensive models and methods. For example, when Einstein developed the Special and General Theories of Relativity, he did not in any way refute or discount Newton's Principia. On the contrary, if the astronomically large, the vanishingly small, and the extremely fast are removed from Einstein's theories – all phenomena Newton could not have observed – Newton's equations are what remain. Einstein's theories are expansions and refinements of Newton's theories and, thus, increase our confidence in Newton's work.

A linearized, pragmatic scheme of the four points above is sometimes offered as a guideline for proceeding:[68]

- Define a question

- Gather information and resources (observe)

- Form an explanatory hypothesis

- Test the hypothesis by performing an experiment and collecting data in a reproducible manner

- Analyze the data

- Interpret the data and draw conclusions that serve as a starting point for new hypothesis

- Publish results

- Retest (frequently done by other scientists)

The iterative cycle inherent in this step-by-step method goes from point 3 to 6 back to 3 again.

While this schema outlines a typical hypothesis/testing method,[69] it should also be noted that a number of philosophers, historians and sociologists of science (perhaps most notably Paul Feyerabend) claim that such descriptions of scientific method have little relation to the ways that science is actually practiced.

Characterizations

The scientific method depends upon increasingly sophisticated characterizations of the subjects of investigation. (The subjects can also be called unsolved problems or the unknowns.) For example, Benjamin Franklin conjectured, correctly, that St. Elmo's fire was electrical in nature, but it has taken a long series of experiments and theoretical changes to establish this. While seeking the pertinent properties of the subjects, careful thought may also entail some definitions and observations; the observations often demand careful measurements and/or counting.

The systematic, careful collection of measurements or counts of relevant quantities is often the critical difference between pseudo-sciences, such as alchemy, and science, such as chemistry or biology. Scientific measurements are usually tabulated, graphed, or mapped, and statistical manipulations, such as correlation and regression, performed on them. The measurements might be made in a controlled setting, such as a laboratory, or made on more or less inaccessible or unmanipulatable objects such as stars or human populations. The measurements often require specialized scientific instruments such as thermometers, spectroscopes, particle accelerators, or voltmeters, and the progress of a scientific field is usually intimately tied to their invention and improvement.

I am not accustomed to saying anything with certainty after only one or two observations.

Uncertainty

Measurements in scientific work are also usually accompanied by estimates of their uncertainty. The uncertainty is often estimated by making repeated measurements of the desired quantity. Uncertainties may also be calculated by consideration of the uncertainties of the individual underlying quantities used. Counts of things, such as the number of people in a nation at a particular time, may also have an uncertainty due to data collection limitations. Or counts may represent a sample of desired quantities, with an uncertainty that depends upon the sampling method used and the number of samples taken.

Definition

Measurements demand the use of operational definitions of relevant quantities. That is, a scientific quantity is described or defined by how it is measured, as opposed to some more vague, inexact or "idealized" definition. For example, electric current, measured in amperes, may be operationally defined in terms of the mass of silver deposited in a certain time on an electrode in an electrochemical device that is described in some detail. The operational definition of a thing often relies on comparisons with standards: the operational definition of "mass" ultimately relies on the use of an artifact, such as a particular kilogram of platinum-iridium kept in a laboratory in France.

The scientific definition of a term sometimes differs substantially from its natural language usage. For example, mass and weight overlap in meaning in common discourse, but have distinct meanings in mechanics. Scientific quantities are often characterized by their units of measure which can later be described in terms of conventional physical units when communicating the work.

New theories are sometimes developed after realizing certain terms have not previously been sufficiently clearly defined. For example, Albert Einstein's first paper on relativity begins by defining simultaneity and the means for determining length. These ideas were skipped over by Isaac Newton with, "I do not define time, space, place and motion, as being well known to all." Einstein's paper then demonstrates that they (viz., absolute time and length independent of motion) were approximations. Francis Crick cautions us that when characterizing a subject, however, it can be premature to define something when it remains ill-understood.[71] In Crick's study of consciousness, he actually found it easier to study awareness in the visual system, rather than to study free will, for example. His cautionary example was the gene; the gene was much more poorly understood before Watson and Crick's pioneering discovery of the structure of DNA; it would have been counterproductive to spend much time on the definition of the gene, before them.

DNA-characterizations

The history of the discovery of the structure of DNA is a classic example of the elements of the scientific method: in 1950 it was known that genetic inheritance had a mathematical description, starting with the studies of Gregor Mendel, and that DNA contained genetic information (Oswald Avery's transforming principle).[31] But the mechanism of storing genetic information (i.e., genes) in DNA was unclear. Researchers in Bragg's laboratory at Cambridge University made X-ray diffraction pictures of various molecules, starting with crystals of salt, and proceeding to more complicated substances. Using clues painstakingly assembled over decades, beginning with its chemical composition, it was determined that it should be possible to characterize the physical structure of DNA, and the X-ray images would be the vehicle.[72] ..2. DNA-hypotheses

Another example: precession of Mercury

The characterization element can require extended and extensive study, even centuries. It took thousands of years of measurements, from the Chaldean, Indian, Persian, Greek, Arabic and European astronomers, to fully record the motion of planet Earth. Newton was able to include those measurements into consequences of his laws of motion. But the perihelion of the planet Mercury's orbit exhibits a precession that cannot be fully explained by Newton's laws of motion (see diagram to the right), as Leverrier pointed out in 1859. The observed difference for Mercury's precession between Newtonian theory and observation was one of the things that occurred to Einstein as a possible early test of his theory of General Relativity. His relativistic calculations matched observation much more closely than did Newtonian theory. The difference is approximately 43 arc-seconds per century.

Hypothesis development

A hypothesis is a suggested explanation of a phenomenon, or alternately a reasoned proposal suggesting a possible correlation between or among a set of phenomena.

Normally hypotheses have the form of a mathematical model. Sometimes, but not always, they can also be formulated as existential statements, stating that some particular instance of the phenomenon being studied has some characteristic and causal explanations, which have the general form of universal statements, stating that every instance of the phenomenon has a particular characteristic.

Scientists are free to use whatever resources they have – their own creativity, ideas from other fields, inductive reasoning, Bayesian inference, and so on – to imagine possible explanations for a phenomenon under study. Charles Sanders Peirce, borrowing a page from Aristotle (Prior Analytics, 2.25) described the incipient stages of inquiry, instigated by the "irritation of doubt" to venture a plausible guess, as abductive reasoning. The history of science is filled with stories of scientists claiming a "flash of inspiration", or a hunch, which then motivated them to look for evidence to support or refute their idea. Michael Polanyi made such creativity the centerpiece of his discussion of methodology.

William Glen observes that

- the success of a hypothesis, or its service to science, lies not simply in its perceived "truth", or power to displace, subsume or reduce a predecessor idea, but perhaps more in its ability to stimulate the research that will illuminate ... bald suppositions and areas of vagueness.[73]

In general scientists tend to look for theories that are "elegant" or "beautiful". In contrast to the usual English use of these terms, they here refer to a theory in accordance with the known facts, which is nevertheless relatively simple and easy to handle. Occam's Razor serves as a rule of thumb for choosing the most desirable amongst a group of equally explanatory hypotheses.

DNA-hypotheses

Linus Pauling proposed that DNA might be a triple helix.[74] This hypothesis was also considered by Francis Crick and James D. Watson but discarded. When Watson and Crick learned of Pauling's hypothesis, they understood from existing data that Pauling was wrong[75] and that Pauling would soon admit his difficulties with that structure. So, the race was on to figure out the correct structure (except that Pauling did not realize at the time that he was in a race) ..3. DNA-predictions

Predictions from the hypothesis

Any useful hypothesis will enable predictions, by reasoning including deductive reasoning. It might predict the outcome of an experiment in a laboratory setting or the observation of a phenomenon in nature. The prediction can also be statistical and deal only with probabilities.

It is essential that the outcome of testing such a prediction be currently unknown. Only in this case does a successful outcome increase the probability that the hypothesis is true. If the outcome is already known, it is called a consequence and should have already been considered while formulating the hypothesis.

If the predictions are not accessible by observation or experience, the hypothesis is not yet testable and so will remain to that extent unscientific in a strict sense. A new technology or theory might make the necessary experiments feasible. Thus, much scientifically based speculation might convince one (or many) that the hypothesis that other intelligent species exist is true. But since there no experiment now known which can test this hypothesis, science itself can have little to say about the possibility. In future, some new technique might lead to an experimental test and the speculation would then become part of accepted science.

DNA-predictions

James D. Watson, Francis Crick, and others hypothesized that DNA had a helical structure. This implied that DNA's X-ray diffraction pattern would be 'x shaped'.[34][76] This prediction followed from the work of Cochran, Crick and Vand[35] (and independently by Stokes). The Cochran-Crick-Vand-Stokes theorem provided a mathematical explanation for the empirical observation that diffraction from helical structures produces x shaped patterns.

In their first paper, Watson and Crick also noted that the double helix structure they proposed provided a simple mechanism for DNA replication, writing, "It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material".[77] ..4. DNA-experiments

Another example: general relativity

Einstein's theory of General Relativity makes several specific predictions about the observable structure of space-time, such as that light bends in a gravitational field, and that the amount of bending depends in a precise way on the strength of that gravitational field. Arthur Eddington's observations made during a 1919 solar eclipse supported General Relativity rather than Newtonian gravitation.[78]

Experiments

Once predictions are made, they can be sought by experiments. If the test results contradict the predictions, the hypotheses which entailed them are called into question and become less tenable. Sometimes the experiments are conducted incorrectly or are not very well designed, when compared to a crucial experiment. If the experimental results confirm the predictions, then the hypotheses are considered more likely to be correct, but might still be wrong and continue to be subject to further testing. The experimental control is a technique for dealing with observational error. This technique uses the contrast between multiple samples (or observations) under differing conditions to see what varies or what remains the same. We vary the conditions for each measurement, to help isolate what has changed. Mill's canons can then help us figure out what the important factor is.[79] Factor analysis is one technique for discovering the important factor in an effect.

Depending on the predictions, the experiments can have different shapes. It could be a classical experiment in a laboratory setting, a double-blind study or an archaeological excavation. Even taking a plane from New York to Paris is an experiment which tests the aerodynamical hypotheses used for constructing the plane.

Scientists assume an attitude of openness and accountability on the part of those conducting an experiment. Detailed record keeping is essential, to aid in recording and reporting on the experimental results, and supports the effectiveness and integrity of the procedure. They will also assist in reproducing the experimental results, likely by others. Traces of this approach can be seen in the work of Hipparchus (190–120 BCE), when determining a value for the precession of the Earth, while controlled experiments can be seen in the works of Jābir ibn Hayyān (721–815 CE), al-Battani (853–929) and Alhazen (965–1039).[80]

DNA-experiments

Watson and Crick showed an initial (and incorrect) proposal for the structure of DNA to a team from Kings College – Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins, and Raymond Gosling. Franklin immediately spotted the flaws which concerned the water content. Later Watson saw Franklin's detailed X-ray diffraction images which showed an X-shape and was able to confirm the structure was helical.[36][37] This rekindled Watson and Crick's model building and led to the correct structure. ..1. DNA-characterizations

Evaluation and improvement

The scientific method is iterative. At any stage it is possible to refine its accuracy and precision, so that some consideration will lead the scientist to repeat an earlier part of the process. Failure to develop an interesting hypothesis may lead a scientist to re-define the subject under consideration. Failure of a hypothesis to produce interesting and testable predictions may lead to reconsideration of the hypothesis or of the definition of the subject. Failure of an experiment to produce interesting results may lead a scientist to reconsider the experimental method, the hypothesis, or the definition of the subject.

Other scientists may start their own research and enter the process at any stage. They might adopt the characterization and formulate their own hypothesis, or they might adopt the hypothesis and deduce their own predictions. Often the experiment is not done by the person who made the prediction, and the characterization is based on experiments done by someone else. Published results of experiments can also serve as a hypothesis predicting their own reproducibility.

DNA-iterations

After considerable fruitless experimentation, being discouraged by their superior from continuing, and numerous false starts,[81][82][83] Watson and Crick were able to infer the essential structure of DNA by concrete modeling of the physical shapes of the nucleotides which comprise it.[38][84] They were guided by the bond lengths which had been deduced by Linus Pauling and by Rosalind Franklin's X-ray diffraction images. ..DNA Example

Confirmation

Science is a social enterprise, and scientific work tends to be accepted by the scientific community when it has been confirmed. Crucially, experimental and theoretical results must be reproduced by others within the scientific community. Researchers have given their lives for this vision; Georg Wilhelm Richmann was killed by ball lightning (1753) when attempting to replicate the 1752 kite-flying experiment of Benjamin Franklin.[85]

To protect against bad science and fraudulent data, government research-granting agencies such as the National Science Foundation, and science journals, including Nature and Science, have a policy that researchers must archive their data and methods so that other researchers can test the data and methods and build on the research that has gone before. Scientific data archiving can be done at a number of national archives in the U.S. or in the World Data Center.

Models of scientific inquiry

Classical model

The classical model of scientific inquiry derives from Aristotle,[86] who distinguished the forms of approximate and exact reasoning, set out the threefold scheme of abductive, deductive, and inductive inference, and also treated the compound forms such as reasoning by analogy.

Pragmatic model

In 1877,[17] Charles Sanders Peirce (/ˈpɜːrs/ like "purse"; 1839–1914) characterized inquiry in general not as the pursuit of truth per se but as the struggle to move from irritating, inhibitory doubts born of surprises, disagreements, and the like, and to reach a secure belief, belief being that on which one is prepared to act. He framed scientific inquiry as part of a broader spectrum and as spurred, like inquiry generally, by actual doubt, not mere verbal or hyperbolic doubt, which he held to be fruitless.[87] He outlined four methods of settling opinion, ordered from least to most successful:

- The method of tenacity (policy of sticking to initial belief) – which brings comforts and decisiveness but leads to trying to ignore contrary information and others' views as if truth were intrinsically private, not public. It goes against the social impulse and easily falters since one may well notice when another's opinion is as good as one's own initial opinion. Its successes can shine but tend to be transitory.[88]

- The method of authority – which overcomes disagreements but sometimes brutally. Its successes can be majestic and long-lived, but it cannot operate thoroughly enough to suppress doubts indefinitely, especially when people learn of other societies present and past.

- The method of the a priori – which promotes conformity less brutally but fosters opinions as something like tastes, arising in conversation and comparisons of perspectives in terms of "what is agreeable to reason." Thereby it depends on fashion in paradigms and goes in circles over time. It is more intellectual and respectable but, like the first two methods, sustains accidental and capricious beliefs, destining some minds to doubt it.

- The scientific method – the method wherein inquiry regards itself as fallible and purposely tests itself and criticizes, corrects, and improves itself.

Peirce held that slow, stumbling ratiocination can be dangerously inferior to instinct and traditional sentiment in practical matters, and that the scientific method is best suited to theoretical research,[89] which in turn should not be trammeled by the other methods and practical ends; reason's "first rule" is that, in order to learn, one must desire to learn and, as a corollary, must not block the way of inquiry.[90] The scientific method excels the others by being deliberately designed to arrive – eventually – at the most secure beliefs, upon which the most successful practices can be based. Starting from the idea that people seek not truth per se but instead to subdue irritating, inhibitory doubt, Peirce showed how, through the struggle, some can come to submit to truth for the sake of belief's integrity, seek as truth the guidance of potential practice correctly to its given goal, and wed themselves to the scientific method.[17][20]

For Peirce, rational inquiry implies presuppositions about truth and the real; to reason is to presuppose (and at least to hope), as a principle of the reasoner's self-regulation, that the real is discoverable and independent of our vagaries of opinion. In that vein he defined truth as the correspondence of a sign (in particular, a proposition) to its object and, pragmatically, not as actual consensus of some definite, finite community (such that to inquire would be to poll the experts), but instead as that final opinion which all investigators would reach sooner or later but still inevitably, if they were to push investigation far enough, even when they start from different points.[91] In tandem he defined the real as a true sign's object (be that object a possibility or quality, or an actuality or brute fact, or a necessity or norm or law), which is what it is independently of any finite community's opinion and, pragmatically, depends only on the final opinion destined in a sufficient investigation. That is a destination as far, or near, as the truth itself to you or me or the given finite community. Thus, his theory of inquiry boils down to "Do the science." Those conceptions of truth and the real involve the idea of a community both without definite limits (and thus potentially self-correcting as far as needed) and capable of definite increase of knowledge.[92] As inference, "logic is rooted in the social principle" since it depends on a standpoint that is, in a sense, unlimited.[93]

Paying special attention to the generation of explanations, Peirce outlined the scientific method as a coordination of three kinds of inference in a purposeful cycle aimed at settling doubts, as follows (in §III–IV in "A Neglected Argument"[5] except as otherwise noted):

- Abduction (or retroduction). Guessing, inference to explanatory hypotheses for selection of those best worth trying. From abduction, Peirce distinguishes induction as inferring, on the basis of tests, the proportion of truth in the hypothesis. Every inquiry, whether into ideas, brute facts, or norms and laws, arises from surprising observations in one or more of those realms (and for example at any stage of an inquiry already underway). All explanatory content of theories comes from abduction, which guesses a new or outside idea so as to account in a simple, economical way for a surprising or complicative phenomenon. Oftenest, even a well-prepared mind guesses wrong. But the modicum of success of our guesses far exceeds that of sheer luck and seems born of attunement to nature by instincts developed or inherent, especially insofar as best guesses are optimally plausible and simple in the sense, said Peirce, of the "facile and natural", as by Galileo's natural light of reason and as distinct from "logical simplicity". Abduction is the most fertile but least secure mode of inference. Its general rationale is inductive: it succeeds often enough and, without it, there is no hope of sufficiently expediting inquiry (often multi-generational) toward new truths.[94] Coordinative method leads from abducing a plausible hypothesis to judging it for its testability[95] and for how its trial would economize inquiry itself.[96] Peirce calls his pragmatism "the logic of abduction".[97] His pragmatic maxim is: "Consider what effects that might conceivably have practical bearings you conceive the objects of your conception to have. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object".[91] His pragmatism is a method of reducing conceptual confusions fruitfully by equating the meaning of any conception with the conceivable practical implications of its object's conceived effects—a method of experimentational mental reflection hospitable to forming hypotheses and conducive to testing them. It favors efficiency. The hypothesis, being insecure, needs to have practical implications leading at least to mental tests and, in science, lending themselves to scientific tests. A simple but unlikely guess, if uncostly to test for falsity, may belong first in line for testing. A guess is intrinsically worth testing if it has instinctive plausibility or reasoned objective probability, while subjective likelihood, though reasoned, can be misleadingly seductive. Guesses can be chosen for trial strategically, for their caution (for which Peirce gave as example the game of Twenty Questions), breadth, and incomplexity.[98] One can hope to discover only that which time would reveal through a learner's sufficient experience anyway, so the point is to expedite it; the economy of research is what demands the leap, so to speak, of abduction and governs its art.[96]

- Deduction. Two stages:

- Explication. Unclearly premissed, but deductive, analysis of the hypothesis in order to render its parts as clear as possible.

- Demonstration: Deductive Argumentation, Euclidean in procedure. Explicit deduction of hypothesis's consequences as predictions, for induction to test, about evidence to be found. Corollarial or, if needed, Theorematic.

- Induction. The long-run validity of the rule of induction is deducible from the principle (presuppositional to reasoning in general[91]) that the real is only the object of the final opinion to which adequate investigation would lead;[99] anything to which no such process would ever lead would not be real. Induction involving ongoing tests or observations follows a method which, sufficiently persisted in, will diminish its error below any predesignate degree. Three stages:

- Classification. Unclearly premissed, but inductive, classing of objects of experience under general ideas.

- Probation: direct inductive argumentation. Crude (the enumeration of instances) or gradual (new estimate of proportion of truth in the hypothesis after each test). Gradual induction is qualitative or quantitative; if qualitative, then dependent on weightings of qualities or characters;[100] if quantitative, then dependent on measurements, or on statistics, or on countings.

- Sentential Induction. "...which, by inductive reasonings, appraises the different probations singly, then their combinations, then makes self-appraisal of these very appraisals themselves, and passes final judgment on the whole result".

Communication and community

Frequently the scientific method is employed not only by a single person, but also by several people cooperating directly or indirectly. Such cooperation can be regarded as an important element of a scientific community. Various standards of scientific methodology are used within such an environment.

Peer review evaluation

Scientific journals use a process of peer review, in which scientists' manuscripts are submitted by editors of scientific journals to (usually one to three) fellow (usually anonymous) scientists familiar with the field for evaluation. In certain journals, the journal itself selects the referees; while in others (especially journals that are extremely specialized), the manuscript author might recommend referees. The referees may or may not recommend publication, or they might recommend publication with suggested modifications, or sometimes, publication in another journal. This standard is practiced to various degrees by different journals, and can have the effect of keeping the literature free of obvious errors and to generally improve the quality of the material, especially in the journals who use the standard most rigorously. The peer review process can have limitations when considering research outside the conventional scientific paradigm: problems of "groupthink" can interfere with open and fair deliberation of some new research.[101]

Documentation and replication

Sometimes experimenters may make systematic errors during their experiments, veer from standard methods and practices (Pathological science) for various reasons, or, in rare cases, deliberately report false results. Occasionally because of this then, other scientists might attempt to repeat the experiments in order to duplicate the results.

Archiving

Researchers sometimes practice scientific data archiving, such as in compliance with the policies of government funding agencies and scientific journals. In these cases, detailed records of their experimental procedures, raw data, statistical analyses and source code can be preserved in order to provide evidence of the methodology and practice of the procedure and assist in any potential future attempts to reproduce the result. These procedural records may also assist in the conception of new experiments to test the hypothesis, and may prove useful to engineers who might examine the potential practical applications of a discovery.

Data sharing

When additional information is needed before a study can be reproduced, the author of the study might be asked to provide it. They might provide it, or if the author refuses to share data, appeals can be made to the journal editors who published the study or to the institution which funded the research.

Limitations

Since it is impossible for a scientist to record everything that took place in an experiment, facts selected for their apparent relevance are reported. This may lead, unavoidably, to problems later if some supposedly irrelevant feature is questioned. For example, Heinrich Hertz did not report the size of the room used to test Maxwell's equations, which later turned out to account for a small deviation in the results. The problem is that parts of the theory itself need to be assumed in order to select and report the experimental conditions. The observations are hence sometimes described as being 'theory-laden'.

Dimensions of practice

The primary constraints on contemporary science are:

- Publication, i.e. Peer review

- Resources (mostly funding)

It has not always been like this: in the old days of the "gentleman scientist" funding (and to a lesser extent publication) were far weaker constraints.

Both of these constraints indirectly require scientific method – work that violates the constraints will be difficult to publish and difficult to get funded. Journals require submitted papers to conform to "good scientific practice" and to a degree this can be enforced by peer review. Originality, importance and interest are more important – see for example the author guidelines for Nature.

Philosophy and sociology of science

Philosophy of science looks at the underpinning logic of the scientific method, at what separates science from non-science, and the ethic that is implicit in science. There are basic assumptions, derived from philosophy by at least one prominent scientist, that form the base of the scientific method – namely, that reality is objective and consistent, that humans have the capacity to perceive reality accurately, and that rational explanations exist for elements of the real world.[102] These assumptions from methodological naturalism form a basis on which science may be grounded. Logical Positivist, empiricist, falsificationist, and other theories have criticized these assumptions and given alternative accounts of the logic of science, but each has also itself been criticized.

Thomas Kuhn examined the history of science in his The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, and found that the actual method used by scientists differed dramatically from the then-espoused method. His observations of science practice are essentially sociological and do not speak to how science is or can be practiced in other times and other cultures.

Norwood Russell Hanson, Imre Lakatos and Thomas Kuhn have done extensive work on the "theory laden" character of observation. Hanson (1958) first coined the term for the idea that all observation is dependent on the conceptual framework of the observer, using the concept of gestalt to show how preconceptions can affect both observation and description.[103] He opens Chapter 1 with a discussion of the Golgi bodies and their initial rejection as an artefact of staining technique, and a discussion of Brahe and Kepler observing the dawn and seeing a "different" sun rise despite the same physiological phenomenon. Kuhn[104] and Feyerabend[105] acknowledge the pioneering significance of his work.

Kuhn (1961) said the scientist generally has a theory in mind before designing and undertaking experiments so as to make empirical observations, and that the "route from theory to measurement can almost never be traveled backward". This implies that the way in which theory is tested is dictated by the nature of the theory itself, which led Kuhn (1961, p. 166) to argue that "once it has been adopted by a profession ... no theory is recognized to be testable by any quantitative tests that it has not already passed".[106]

Paul Feyerabend similarly examined the history of science, and was led to deny that science is genuinely a methodological process. In his book Against Method he argues that scientific progress is not the result of applying any particular method. In essence, he says that for any specific method or norm of science, one can find a historic episode where violating it has contributed to the progress of science. Thus, if believers in scientific method wish to express a single universally valid rule, Feyerabend jokingly suggests, it should be 'anything goes'.[107] Criticisms such as his led to the strong programme, a radical approach to the sociology of science.

The postmodernist critiques of science have themselves been the subject of intense controversy. This ongoing debate, known as the science wars, is the result of conflicting values and assumptions between the postmodernist and realist camps. Whereas postmodernists assert that scientific knowledge is simply another discourse (note that this term has special meaning in this context) and not representative of any form of fundamental truth, realists in the scientific community maintain that scientific knowledge does reveal real and fundamental truths about reality. Many books have been written by scientists which take on this problem and challenge the assertions of the postmodernists while defending science as a legitimate method of deriving truth.[108]

Role of chance in discovery

Somewhere between 33% and 50% of all scientific discoveries are estimated to have been stumbled upon, rather than sought out. This may explain why scientists so often express that they were lucky.[109] Louis Pasteur is credited with the famous saying that "Luck favours the prepared mind", but some psychologists have begun to study what it means to be 'prepared for luck' in the scientific context. Research is showing that scientists are taught various heuristics that tend to harness chance and the unexpected.[109][110] This is what Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls "Anti-fragility"; while some systems of investigation are fragile in the face of human error, human bias, and randomness, the scientific method is more than resistant or tough – it actually benefits from such randomness in many ways (it is anti-fragile). Taleb believes that the more anti-fragile the system, the more it will flourish in the real world.[21]

Psychologist Kevin Dunbar says the process of discovery often starts with researchers finding bugs in their experiments. These unexpected results lead researchers to try to fix what they think is an error in their method. Eventually, the researcher decides the error is too persistent and systematic to be a coincidence. The highly controlled, cautious and curious aspects of the scientific method are thus what make it well suited for identifying such persistent systematic errors. At this point, the researcher will begin to think of theoretical explanations for the error, often seeking the help of colleagues across different domains of expertise.[109][110]

History

The development of the scientific method emerges in the history of science itself. Ancient Egyptian documents describe empirical methods in astronomy,[112] mathematics,[113] and medicine.[114] The Greeks made contributions to the scientific method, most notably through Aristotle in his six works of logic collected as the Organon. Aristotle's inductive-deductive method used inductions from observations to infer general principles, deductions from those principles to check against further observations, and more cycles of induction and deduction to continue the advance of knowledge[115]

According to Karl Popper, Parmenides (fl. 5th century BCE) had conceived an axiomatic-deductive method.[116] According to David Lindberg, Aristotle (4th century BCE) wrote about the scientific method even if he and his followers did not actually follow what he said.[65] Lindberg also notes that Ptolemy (2nd century CE) and Ibn al-Haytham (11th century CE) are among the early examples of people who carried out scientific experiments.[117] Also, John Losee writes that "the Physics and the Metaphysics contain discussions of certain aspects of scientific method", of which, he says "Aristotle viewed scientific inquiry as a progression from observations to general principles and back to observations."[118]

Early Christian leaders such as Clement of Alexandria (150–215) and Basil of Caesarea (330–379) encouraged future generations to view the Greek wisdom as "handmaidens to theology" and science was considered a means to more accurate understanding of the Bible and of God.[119]:pp.4–5 Augustine of Hippo (354–430) who contributed great philosophical wealth to the Latin Middle Ages, advocated the study of science and was wary of philosophies that disagreed with the Bible, such as astrology and the Greek belief that the world had no beginning.[119]:p.5 This Christian accommodation with Greek science "laid a foundation for the later widespread, intensive study of natural philosophy during the Late Middle Ages."[119]:pp.8,9 However, the division of Latin-speaking Western Europe from the Greek-speaking East,[119]:p.18 followed by barbarian invasions, the Plague of Justinian, and the Islamic conquests,[120] resulted in the West largely losing access to Greek wisdom.

By the 8th century Islam had conquered the Christian lands[121] of Syria, Iraq, Iran and Egypt.[122] This swift conquest further severed Western Europe from many of the great works of Aristotle, Plato, Euclid and others, many of which were housed in the great library of Alexandria. Having come upon such a wealth of knowledge, the Arabs, who viewed non-Arab languages as inferior, even as a source of pollution,[123] employed conquered Christians and Jews to translate these works from the native Greek and Syriac into Arabic.[124]

Thus equipped, Arab philosopher Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham) performed optical and physiological experiments, reported in his manifold works, the most famous being Book of Optics (1021).[125] He was thus a forerunner of scientific method, having understood that a controlled environment involving experimentation and measurement is required in order to draw educated conclusions. Other Arab polymaths of the same era produced copious works on mathematics, philosophy, astronomy and alchemy. Most stuck closely to Aristotle, being hesitant to admit that some of Aristotle's thinking was errant,[126] while others strongly criticized him.

During these years, occasionally a paraphrased translation from the Arabic, which itself had been translated from Greek and Syriac, might make its way to the West for scholarly study. It was not until 1204, during which the Latins conquered and took Constantinople from the Byzantines in the name of the fourth Crusade, that a renewed scholarly interest in the original Greek manuscripts began to grow. Due to the new easier access to the libraries of Constantinople by Western scholars, a certain revival in the study and analysis of the original Greek texts by Western scholars began.[127] From that point a functional scientific method that would launch modern science was on the horizon.

Grosseteste (1175–1253), an English statesman, scientist and Christian theologian, was "the principal figure" in bringing about "a more adequate method of scientific inquiry" by which "medieval scientists were able eventually to outstrip their ancient European and Muslim teachers" (Dales 1973, p. 62). ... His thinking influenced Roger Bacon, who spread Grosseteste's ideas from Oxford to the University of Paris during a visit there in the 1240s. From the prestigious universities in Oxford and Paris, the new experimental science spread rapidly throughout the medieval universities: "And so it went to Galileo, William Gilbert, Francis Bacon, William Harvey, Descartes, Robert Hooke, Newton, Leibniz, and the world of the seventeenth century" (Crombie 1953, p. 15). "So it went to us as well " (Gauch 2003, pp. 52–53).

Roger Bacon (c. 1214 – c. 1292), an English thinker and experimenter, is recognized by many to be the father of modern scientific method. His view that mathematics was essential to a correct understanding of natural philosophy was considered to be 400 years ahead of its time.[129]:2 He was viewed as "a lone genius proclaiming the truth about time," having correctly calculated the calendar[129]:3 His work in optics provided the platform on which Newton, Descartes, Huygens and others later transformed the science of light. Bacon's groundbreaking advances were due largely to his discovery that experimental science must be based on mathematics. (186–187) His works Opus Majus and De Speculis Comburentibus contain many "carefully drawn diagrams showing Bacon's meticulous investigations into the behavior of light."[129]:66 He gives detailed descriptions of systematic studies using prisms and measurements by which he shows how a rainbow functions.[129]:200

Others who advanced scientific method during this era included Albertus Magnus (c. 1193 – 1280), Theodoric of Freiberg, (c. 1250 – c. 1310), William of Ockham (c. 1285 – c. 1350), and Jean Buridan (c. 1300 – c. 1358). These were not only scientists but leaders of the church – Christian archbishops, friars and priests.

By the late 15th century, the physician-scholar Niccolò Leoniceno was finding errors in Pliny's Natural History. As a physician, Leoniceno was concerned about these botanical errors propagating to the materia medica on which medicines were based.[130] To counter this, a botanical garden was established at Orto botanico di Padova, University of Padua (in use for teaching by 1546), in order that medical students might have empirical access to the plants of a pharmacopia. The philosopher and physician Francisco Sanches was led by his medical training at Rome, 1571–73, and by the philosophical skepticism recently placed in the European mainstream by the publication of Sextus Empiricus' "Outlines of Pyrrhonism", to search for a true method of knowing (modus sciendi), as nothing clear can be known by the methods of Aristotle and his followers[131] – for example, syllogism fails upon circular reasoning. Following the physician Galen's method of medicine, Sanches lists the methods of judgement and experience, which are faulty in the wrong hands,[132] and we are left with the bleak statement That Nothing is Known (1581). This challenge was taken up by René Descartes in the next generation (1637), but at the least, Sanches warns us that we ought to refrain from the methods, summaries, and commentaries on Aristotle, if we seek scientific knowledge. In this, he is echoed by Francis Bacon, also influenced by skepticism; Sanches cites the humanist Juan Luis Vives who sought a better educational system, as well as a statement of human rights as a pathway for improvement of the lot of the poor.

The modern scientific method crystallized no later than in the 17th and 18th centuries. In his work Novum Organum (1620) – a reference to Aristotle's Organon – Francis Bacon outlined a new system of logic to improve upon the old philosophical process of syllogism.[133] Then, in 1637, René Descartes established the framework for scientific method's guiding principles in his treatise, Discourse on Method. The writings of Alhazen, Bacon and Descartes are considered critical in the historical development of the modern scientific method, as are those of John Stuart Mill.[134]

In the late 19th century, Charles Sanders Peirce proposed a schema that would turn out to have considerable influence in the development of current scientific methodology generally. Peirce accelerated the progress on several fronts. Firstly, speaking in broader context in "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878), Peirce outlined an objectively verifiable method to test the truth of putative knowledge on a way that goes beyond mere foundational alternatives, focusing upon both deduction and induction. He thus placed induction and deduction in a complementary rather than competitive context (the latter of which had been the primary trend at least since David Hume, who wrote in the mid-to-late 18th century). Secondly, and of more direct importance to modern method, Peirce put forth the basic schema for hypothesis/testing that continues to prevail today. Extracting the theory of inquiry from its raw materials in classical logic, he refined it in parallel with the early development of symbolic logic to address the then-current problems in scientific reasoning. Peirce examined and articulated the three fundamental modes of reasoning that, as discussed above in this article, play a role in inquiry today, the processes that are currently known as abductive, deductive, and inductive inference. Thirdly, he played a major role in the progress of symbolic logic itself – indeed this was his primary specialty.

Beginning in the 1930s, Karl Popper argued that there is no such thing as inductive reasoning.[135] All inferences ever made, including in science, are purely[136] deductive according to this view. Accordingly, he claimed that the empirical character of science has nothing to do with induction – but with the deductive property of falsifiability that scientific hypotheses have. Contrasting his views with inductivism and positivism, he even denied the existence of the scientific method: "(1) There is no method of discovering a scientific theory (2) There is no method for ascertaining the truth of a scientific hypothesis, i.e., no method of verification; (3) There is no method for ascertaining whether a hypothesis is 'probable', or probably true".[137] Instead, he held that there is only one universal method, a method not particular to science: The negative method of criticism, or colloquially termed trial and error. It covers not only all products of the human mind, including science, mathematics, philosophy, art and so on, but also the evolution of life. Following Peirce and others, Popper argued that science is fallible and has no authority.[137] In contrast to empiricist-inductivist views, he welcomed metaphysics and philosophical discussion and even gave qualified support to myths[138] and pseudosciences.[139] Popper's view has become known as critical rationalism.

Although science in a broad sense existed before the modern era, and in many historical civilizations (as described above), modern science is so distinct in its approach and successful in its results that it now defines what science is in the strictest sense of the term.[140]

Relationship with mathematics

Science is the process of gathering, comparing, and evaluating proposed models against observables. A model can be a simulation, mathematical or chemical formula, or set of proposed steps. Science is like mathematics in that researchers in both disciplines can clearly distinguish what is known from what is unknown at each stage of discovery. Models, in both science and mathematics, need to be internally consistent and also ought to be falsifiable (capable of disproof). In mathematics, a statement need not yet be proven; at such a stage, that statement would be called a conjecture. But when a statement has attained mathematical proof, that statement gains a kind of immortality which is highly prized by mathematicians, and for which some mathematicians devote their lives.[141]

Mathematical work and scientific work can inspire each other.[142] For example, the technical concept of time arose in science, and timelessness was a hallmark of a mathematical topic. But today, the Poincaré conjecture has been proven using time as a mathematical concept in which objects can flow (see Ricci flow).

Nevertheless, the connection between mathematics and reality (and so science to the extent it describes reality) remains obscure. Eugene Wigner's paper, The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences, is a very well known account of the issue from a Nobel Prize-winning physicist. In fact, some observers (including some well known mathematicians such as Gregory Chaitin, and others such as Lakoff and Núñez) have suggested that mathematics is the result of practitioner bias and human limitation (including cultural ones), somewhat like the post-modernist view of science.

George Pólya's work on problem solving,[143] the construction of mathematical proofs, and heuristic[144][145] show that the mathematical method and the scientific method differ in detail, while nevertheless resembling each other in using iterative or recursive steps.

In Pólya's view, understanding involves restating unfamiliar definitions in your own words, resorting to geometrical figures, and questioning what we know and do not know already; analysis, which Pólya takes from Pappus,[146] involves free and heuristic construction of plausible arguments, working backward from the goal, and devising a plan for constructing the proof; synthesis is the strict Euclidean exposition of step-by-step details[147] of the proof; review involves reconsidering and re-examining the result and the path taken to it.

Gauss, when asked how he came about his theorems, once replied "durch planmässiges Tattonieren" (through systematic palpable experimentation).[148]

Imre Lakatos argued that mathematicians actually use contradiction, criticism and revision as principles for improving their work.[149] In like manner to science, where truth is sought, but certainty is not found, in Proofs and refutations (1976), what Lakatos tried to establish was that no theorem of informal mathematics is final or perfect. This means that we should not think that a theorem is ultimately true, only that no counterexample has yet been found. Once a counterexample, i.e. an entity contradicting/not explained by the theorem is found, we adjust the theorem, possibly extending the domain of its validity. This is a continuous way our knowledge accumulates, through the logic and process of proofs and refutations. (If axioms are given for a branch of mathematics, however, Lakatos claimed that proofs from those axioms were tautological, i.e. logically true, by rewriting them, as did Poincaré (Proofs and Refutations, 1976).)

Lakatos proposed an account of mathematical knowledge based on Polya's idea of heuristics. In Proofs and Refutations, Lakatos gave several basic rules for finding proofs and counterexamples to conjectures. He thought that mathematical 'thought experiments' are a valid way to discover mathematical conjectures and proofs.[150]

Relationship with statistics

The scientific method has been extremely successful in bringing the world out of medieval times, especially once it was combined with industrial processes.[151] However, when the scientific method employs statistics as part of its arsenal, there are a number of both mathematical and practical issues that can have a deleterious effect on the reliability of the output of the scientific methods. This is outlined in detail in the most downloaded 2005 scientific paper "Why Most Published Research Findings Are False"[152] ever by John Ioannidis.

The particular points raised are statistical ("The smaller the studies conducted in a scientific field, the less likely the research findings are to be true" and "The greater the flexibility in designs, definitions, outcomes, and analytical modes in a scientific field, the less likely the research findings are to be true.") and economical ("The greater the financial and other interests and prejudices in a scientific field, the less likely the research findings are to be true" and "The hotter a scientific field (with more scientific teams involved), the less likely the research findings are to be true.") Hence: "Most research findings are false for most research designs and for most fields" and "As shown, the majority of modern biomedical research is operating in areas with very low pre- and poststudy probability for true findings." However: "Nevertheless, most new discoveries will continue to stem from hypothesis-generating research with low or very low pre-study odds," which means that *new* discoveries will come from research that, when that research started, had low or very low odds (a low or very low chance) of succeeding. Hence, if the scientific method is used to expand the frontiers of knowledge, research into areas that are outside the mainstream will yield most new discoveries.

See also

Problems and issues

History, philosophy, sociology

Notes

- 1 2 http://idea.ucr.edu/documents/flash/scientific_method/story.htm

- 1 2 Goldhaber & Nieto 2010, p. 940

- ↑ "[4] Rules for the study of natural philosophy", Newton transl 1999, pp. 794–6, after Book 3, The System of the World.

- ↑ From the Oxford English Dictionary definition for "scientific".

- 1 2 3 Peirce (1908), "A Neglected Argument for the Reality of God", Hibbert Journal v. 7, pp. 90–112. s:A Neglected Argument for the Reality of God with added notes. Reprinted with previously unpublished part, Collected Papers v. 6, paragraphs 452–85, The Essential Peirce v. 2, pp. 434–50, and elsewhere.

- ↑ See, for example, Galileo 1638. His thought experiments disprove Aristotle's physics of falling bodies, in Two New Sciences.

- ↑ Popper 1959:p273

- 1 2 Karl R. Popper, Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge, Routledge, 2003 ISBN 0-415-28594-1

- ↑ Gauch, Hugh G. (2003). Scientific Method in Practice (Reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521017084. Retrieved 2015-01-26.

The scientific method 'is often misrepresented as a fixed sequence of steps,' rather than being seen for what it truly is, 'a highly variable and creative process' (AAAS 2000:18). The claim here is that science has general principles that must be mastered to increase productivity and enhance perspective, not that these principles provide a simple and automated sequence of steps to follow.

- 1 2 History of Inductive Science (1837), and in Philosophy of Inductive Science (1840)

- ↑ Jim Al-Khalili (4 January 2009). "The 'first true scientist'". BBC News.

- ↑ Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa (2010). Mind, Brain, and Education Science: A Comprehensive Guide to the New Brain-Based Teaching. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 39. ISBN 9780393706079.

Alhazen (or Al-Haytham; 965–1039 C.E.) was perhaps one of the greatest physicists of all times and a product of the Islamic Golden Age or Islamic Renaissance (7th–13th centuries). He made significant contributions to anatomy, astronomy, engineering, mathematics, medicine, ophthalmology, philosophy, physics, psychology, and visual perception and is primarily attributed as the inventor of the scientific method, for which author Bradley Steffens (2006) describes him as the "first scientist".

- ↑ Peirce, C. S., Collected Papers v. 1, paragraph 74.

- ↑ Morris Kline (1985) Mathematics for the nonmathematician. Courier Dover Publications. p. 284. ISBN 0-486-24823-2

- ↑ Shapere, Dudley (1974). Galileo: A Philosophical Study. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-75007-8.

- ↑ " The thesis of this book, as set forth in Chapter One, is that there are general principles applicable to all the sciences." __ Gauch 2003, p. xv

- 1 2 3 Peirce (1877), "The Fixation of Belief", Popular Science Monthly, v. 12, pp. 1–15. Reprinted often, including (Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce v. 5, paragraphs 358–87), (The Essential Peirce, v. 1, pp. 109–23). Peirce.org Eprint. Wikisource Eprint.

- ↑ Gauch 2003, p. 1 The scientific method can function in the same way; This is the principle of noncontradiction.

- ↑ Francis Bacon(1629) New Organon, lists 4 types of error: Idols of the tribe (error due to the entire human race), the cave (errors due to an individual's own intellect), the marketplace (errors due to false words), and the theater (errors due to incredulous acceptance).

- 1 2 Peirce, C. S., Collected Papers v. 5, in paragraph 582, from 1898:

... [rational] inquiry of every type, fully carried out, has the vital power of self-correction and of growth. This is a property so deeply saturating its inmost nature that it may truly be said that there is but one thing needful for learning the truth, and that is a hearty and active desire to learn what is true.

- 1 2 Taleb contributes a brief description of anti-fragility, http://www.edge.org/q2011/q11_3.html

- ↑ For example, the concept of falsification (first proposed in 1934) formalizes the attempt to disprove hypotheses rather than prove them. Karl R. Popper (1963), 'The Logic of Scientific Discovery'. The Logic of Scientific Discovery pp. 17–20, 249–252, 437–438, and elsewhere.

- Leon Lederman, for teaching physics first, illustrates how to avoid confirmation bias: Ian Shelton, in Chile, was initially skeptical that supernova 1987a was real, but possibly an artifact of instrumentation (null hypothesis), so he went outside and disproved his null hypothesis by observing SN 1987a with the naked eye. The Kamiokande experiment, in Japan, independently observed neutrinos from SN 1987a at the same time.

- ↑ Lindberg 2007, pp. 2–3: "There is a danger that must be avoided. ... If we wish to do justice to the historical enterprise, we must take the past for what it was. And that means we must resist the temptation to scour the past for examples or precursors of modern science. ...My concern will be with the beginnings of scientific theories, the methods by which they were formulated, and the uses to which they were put; ... "