Schwarzschild radius

The Schwarzschild radius (sometimes historically referred to as the gravitational radius) is the radius of a sphere such that, if all the mass of an object were to be compressed within that sphere, the escape velocity from the surface of the sphere would equal the speed of light. An example of an object where the mass is within its Schwarzschild radius is a black hole. Once a stellar remnant collapses to or below this radius, light cannot escape and the object is no longer directly visible, thereby forming a black hole.[1] It is a characteristic radius associated with every quantity of mass. The Schwarzschild radius was named after the German astronomer Karl Schwarzschild, who calculated this exact solution for the theory of general relativity in 1916.

History

In 1916, Karl Schwarzschild obtained the exact solution[2][3] to Einstein's field equations for the gravitational field outside a non-rotating, spherically symmetric body (see Schwarzschild metric). Using the definition  , the solution contained a term of the form

, the solution contained a term of the form  ; where the value of

; where the value of  making this term singular has come to be known as the Schwarzschild radius. The physical significance of this singularity, and whether this singularity could ever occur in nature, was debated for many decades; a general acceptance of the possibility of a black hole did not occur until the second half of the 20th century.

making this term singular has come to be known as the Schwarzschild radius. The physical significance of this singularity, and whether this singularity could ever occur in nature, was debated for many decades; a general acceptance of the possibility of a black hole did not occur until the second half of the 20th century.

Parameters

The Schwarzschild radius of an object is proportional to the mass. Accordingly, the Sun has a Schwarzschild radius of approximately 3.0 km (1.9 mi), whereas Earth's is only about 9.0 mm. The observable universe's mass has a Schwarzschild radius of approximately 13.7 billion light years.[4][5]

(m) (m) |

(g/cm3) (g/cm3) | |

|---|---|---|

| Milky Way | 2.08×1015 (~100,000 ly) | 3.72×10−8 |

| Sun | 2.95×103 | 1.84×1016 |

| Earth | 8.87×10−3 | 2.04×1027 |

| Sagittarius A* (SMBH) | 1.27×1010 | |

| Andromeda (SMBH) | 4.68×1011 | |

| NGC 4889 (SMBH) | 6.2×1013 |

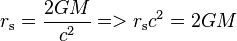

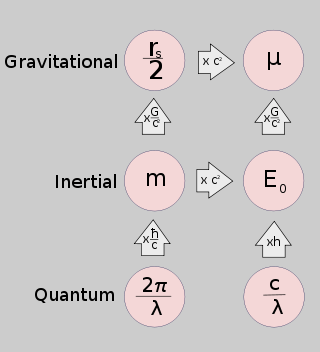

Formula

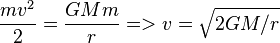

The Schwarzschild radius is the limiting maximum radius of a massive object at which the escape velocity reaches its maximum limit (the speed of light, c). If an object is thrown up from the surface of a massive object at velocity v, its kinetic energy slowly transforms into potential energy, and then back as the object falls back to the surface. Escape velocity is the limiting minimum velocity at which the object continues to slow but never stop until it reaches an infinite distance. So, the sum of its positive kinetic energy and negative potential energy is greater than or equal to zero (i.e. KE = PE).

Therefore, escape velocity can be calculated (from KE = PE) as:

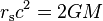

Therefore, at maximum escape velocity (speed of light, c), Schwarzschild radius becomes directly proportional to mass as:

where:

- rs is the Schwarzschild radius;

- G is the gravitational constant;

- M is the mass of the object;

- c is the speed of light in vacuum.

The proportionality constant, 2G/c2, is approximately 1.48×10−27 m/kg, or 2.95 km/M☉.

An object of any density can be large enough to fall within its own Schwarzschild radius,

where:

-

is the volume of the object;

is the volume of the object;

-

is its density.

is its density.

Black hole classification by Schwarzschild radius

Any object whose radius is smaller than its Schwarzschild radius is called a black hole. The surface at the Schwarzschild radius acts as an event horizon in a non-rotating body (a rotating black hole operates slightly differently). Neither light nor particles can escape through this surface from the region inside, hence the name "black hole".

Black holes can be classified based on their Schwarzschild radius, or equivalently, by their density. As the radius is linearly related to mass, while the enclosed volume corresponds to the third power of the radius, small black holes are therefore much more dense than large ones. The volume enclosed in the event horizon of the most massive black holes has a density lower than main sequence stars.

Supermassive black hole

A supermassive black hole (SMBH) is the largest type of black hole, though there are few official criteria on how such an object is considered so, on the order of hundreds of thousands to billions of solar masses. (Supermassive black holes up to 21 billion (2.1 × 1010) M☉ have been detected, such as NGC 4889.)[6] Unlike stellar mass black holes, supermassive black holes have comparatively low densities. (Note that a black hole is a spherical region in space that surrounds the singularity at its center; it is not the singularity itself). With that in mind, the average density of a supermassive black hole can be less than the density of water.

The Schwarzschild radius of a body is proportional to its mass and therefore to its volume, assuming that the body has a constant mass-density.[7] In contrast, the physical radius of the body is proportional to the cube root of its volume. Therefore, as the body accumulates matter at a given fixed density (in this example, 103 kg/m3, the density of water), its Schwarzschild radius will increase more quickly than its physical radius. When a body of this density has grown to around 136 million solar masses (1.36 × 108) M☉, its physical radius would be overtaken by its Schwarzschild radius, and thus it would form a supermassive black hole.

It is thought that supermassive black holes like these do not form immediately from the singular collapse of a cluster of stars. Instead they may begin life as smaller, stellar-sized black holes and grow larger by the accretion of matter, or even of other black holes.

The Schwarzschild radius of the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Center would be approximately 13.3 million kilometres.[8]

Stellar black hole

Stellar black holes have much greater densities than supermassive black holes. If one accumulates matter at nuclear density (the density of the nucleus of an atom, about 1018 kg/m3; neutron stars also reach this density), such an accumulation would fall within its own Schwarzschild radius at about 3 M☉ and thus would be a stellar black hole.

Primordial black hole

A small mass has an extremely small Schwarzschild radius. A mass similar to Mount Everest[9][note 1] has a Schwarzschild radius much smaller than a nanometre.[note 2] Its average density at that size would be so high that no known mechanism could form such extremely compact objects. Such black holes might possibly be formed in an early stage of the evolution of the universe, just after the Big Bang, when densities were extremely high. Therefore these hypothetical miniature black holes are called primordial black holes.

Other uses

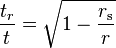

In gravitational time dilation

Gravitational time dilation near a large, slowly rotating, nearly spherical body, such as the Earth or Sun can be reasonably approximated using the Schwarzschild radius as follows:

where:

- tr is the elapsed time for an observer at radial coordinate "r" within the gravitational field;

- t is the elapsed time for an observer distant from the massive object (and therefore outside of the gravitational field);

- r is the radial coordinate of the observer (which is analogous to the classical distance from the center of the object);

- rs is the Schwarzschild radius.

The results of the Pound–Rebka experiment in 1959 were found to be consistent with predictions made by general relativity. By measuring Earth’s gravitational time dilation, this experiment indirectly measured Earth’s Schwarzschild radius.

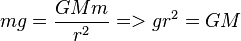

In Newtonian gravitational fields

The Newtonian gravitational field near a large, slowly rotating, nearly spherical body can be reasonably approximated using the Schwarzschild radius as follows:

and

Therefore on dividing above by below:

where:

- g is the gravitational acceleration at radial coordinate "r";

- rs is the Schwarzschild radius of the gravitating central body;

- r is the radial coordinate;

- c is the speed of light in vacuum.

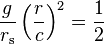

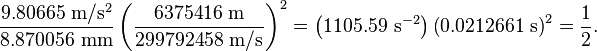

On the surface of the Earth:

In Keplerian orbits

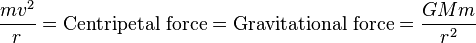

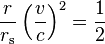

For all circular orbits around a given central body:

Therefore,

but

(derived above)

(derived above)

Therefore,

where:

- r is the orbit radius;

- rs is the Schwarzschild radius of the gravitating central body;

- v is the orbital speed;

- c is the speed of light in vacuum.

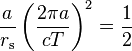

This equality can be generalized to elliptic orbits as follows:

where:

- a is the semi-major axis;

- T is the orbital period.

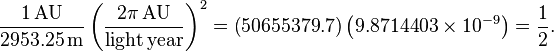

For the Earth orbiting the Sun:

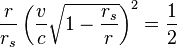

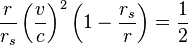

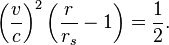

Relativistic circular orbits and the photon sphere

The Keplerian equation for circular orbits can be generalized to the relativistic equation for circular orbits by accounting for time dilation in the velocity term:

This final equation indicates that an object orbiting at the speed of light would have an orbital radius of 1.5 times the Schwarzschild radius. This is a special orbit known as the photon sphere.

See also

- Black hole, a general survey

- Chandrasekhar limit, a second requirement for black hole formation

- John Michell

Classification of black holes by type:

- Static or Schwarzschild black hole

- Rotating or Kerr black hole

- Charged black hole or Newman black hole and Kerr-Newman black hole

A classification of black holes by mass:

- Micro black hole and extra-dimensional black hole

- Primordial black hole, a hypothetical leftover of the Big Bang

- Stellar black hole, which could either be a static black hole or a rotating black hole

- Supermassive black hole, which could also either be a static black hole or a rotating black hole

- Visible universe, if its density is the critical density

Notes

References

- ↑ Chaisson, Eric, and S. McMillan. Astronomy Today. San Francisco, CA: Pearson / Addison Wesley, 2008. Print.

- ↑ K. Schwarzschild, "Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie", Sitzungsberichte der Deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Klasse fur Mathematik, Physik, und Technik (1916) pp 189.

- ↑ K. Schwarzschild, "Über das Gravitationsfeld einer Kugel aus inkompressibler Flussigkeit nach der Einsteinschen Theorie", Sitzungsberichte der Deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Klasse fur Mathematik, Physik, und Technik (1916) pp 424.

- ↑ Valev, Dimitar (October 2008). "Consequences from conservation of the total density of the universe during the expansion". arXiv:1008.0933 [physics.gen-ph].

- ↑ Deza, Michel Marie; Deza, Elena (Oct 28, 2012). Encyclopedia of Distances (2nd ed.). Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 452. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30958-8. ISBN 978-3-642-30958-8. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ↑ McConnell, Nicholas J. (2011-12-08). "Two ten-billion-solar-mass black holes at the centres of giant elliptical galaxies". Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-06. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ↑ Robert H. Sanders (2013). Revealing the Heart of the Galaxy: The Milky Way and its Black Hole. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-107-51274-0.

- ↑ http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/world/article1967154.ece

- 1 2 "How does the mass of one mole of M&M’s compare to the mass of Mount Everest?" (PDF). School of Science and Technology, Singapore. March 2003. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

If Mount Everest is assumed* to be a cone of height 8850 m and radius 5000 m, then its volume can be calculated using the following equation[:] volume = πr2h/3 [...] Mount Everest is composed of granite, which has a density of 2750 kg m−3.

line feed character in|quote=at position 101 (help)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||