Cross section (physics)

The cross section is an effective area that quantifies the intrinsic likelihood of a scattering event when an incident beam strikes a target object, made of discrete particles. The cross section of a particle is the same as the cross section of a hard object, if the probabilities of hitting them with a ray are the same. It is typically denoted σ and measured in units of area.

In scattering experiments, one is often interested in knowing how likely a given event occurs. However, the rate depends strongly on experimental variables such as the density of the target material, the intensity of the beam, or the area of overlap between the beam and the target material. To control for these mundane differences, one can factor out these variables, resulting in an area-like quantity known as the cross section.

Definition

Cross section is associated with a particular event (e.g. elastic collision, a specific chemical reaction, a specific nuclear reaction) involving a certain combination of beam (e.g. light, elementary particles, nuclei) and target material (e.g. colloids, gases, atoms, nuclei). Often there are additional factors that can affect the cross section in complicated ways, such as the energy of the beam.

For a given event, the cross section σ is given by

where

- σ is the cross section of this event (SI units: m2),

- μ is the attenuation coefficient due to the occurrence of this event (SI units: m−1), and

- n is the number density of the target particles (SI units: m-3).

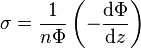

Equivalently, if the target material is a thin slab placed perpendicular to the beam, one may express the cross section in terms of flux:

where

- −dΦ is the amount of flux lost due to the occurrence of this event,

- dz is the thickness of the target material, and

- Φ is the flux of the incident beam.

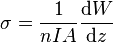

For discrete events involving a beam of particles, the cross section σ is given by:

where

- dW is the rate at which the event occurs (SI units: s−1),

- I is the particle flux (or intensity) of the incident beam (SI units: m−2 s−1), and

- A is the area of overlap between the beam and the target (SI units: m2).

Schematically, an event is said to have a cross-section of σ if its rate is equal to that of collisions in an idealized classical experiment where:

- the beam is replaced by a stream of inert point-like particles, and

- the target particles are replaced by inert and impenetrable disks of area σ (and hence the name “cross-section”),

with all other experimental variables kept the same as the original experiment.

Differential cross section

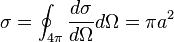

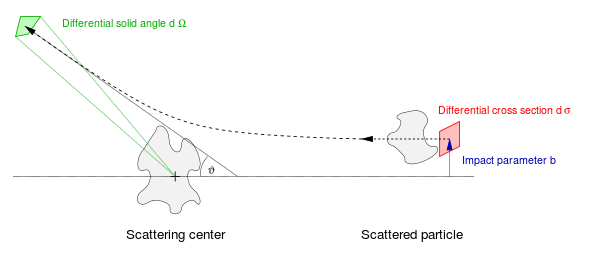

The cross section is a scalar that only quantifies the intrinsic rate of an event. In contrast, the differential cross section dσ/dΩ is a function that quantifies the intrinsic rate at which the scattered projectiles can be detected at a given angle (where Ω represents solid angle).

Conventionally, a spherical coordinate system is used, with the target placed at the origin and the z-axis of this coordinate system aligned with the incident beam. The angle θ is the scattering angle, measured between the incident beam and the scattered beam and the φ is the azimuthal angle. Many types of scattering processes possess azimuthal symmetry and therefore do not depend on φ.

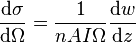

The differential cross section dσ/dΩ at an angle (θ, φ) is related to the rate of detection dw at that angle by

where Ω is the angular span of the detector (SI unit: sr), which is assumed to be small and have perfect detection ratio.

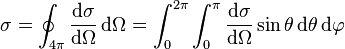

The cross section σ may be recovered by integrating the differential cross section dσ/dΩ over the full solid angle (4 π steradians):

It is common to omit the “differential” qualifier when the type of cross section can be inferred from context. In this case, σ may be referred to as the integral cross section or total cross section. The latter term may be confusing in contexts where multiple events are involved, since “total” can also refer to the sum of cross sections over all events.

The differential cross section is extremely useful quantity in many fields of physics, as measuring it can reveal a great amount of information about the internal structure of the target particles. For example, the differential cross section of Rutherford scattering provided strong evidence for the existence of the atomic nucleus.

Units

Although the SI unit of total cross sections is m2, smaller units are usually used in practice.

When the scattered radiation is visible light, it is conventional to measure the path length in centimetres. To avoid the need for conversion factors, the scattering cross-section is expressed in cm2 and the number concentration in cm−3. The measurement of the scattering of visible light is known as nephelometry, and is effective for particles of 2–50 µm in diameter: as such, it is widely used in meteorology and in the measurement of atmospheric pollution.

The scattering of X-rays can also be described in terms of scattering cross-sections, in which case Å2 is a convenient unit: Å2 = 10−20 m2 = 104 pm2.

In nuclear and particle physics, the conventional unit is b, where b = 10−28 m2 = 100 fm2.[1] Smaller prefixed units such as mb and μb are also widely used. Correspondingly, the differential cross section can be measured in units such as mb sr−1.

Classical scattering

In a simple classical experiment where a single particle is scattered off a rigid target,

the impact parameter is the perpendicular offset of the trajectory of the incoming particle. The differential of the cross section is the area element in the plane of the impact parameter, i.e.  , where

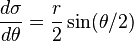

, where  is the impact parameter. The differential cross section is the differential quotient of this area element by the solid angle element in the direction of the particle exit trajectory:

is the impact parameter. The differential cross section is the differential quotient of this area element by the solid angle element in the direction of the particle exit trajectory:

It describes the change in the impact parameter necessary to cause a given change in the exit trajectory direction. The definition is slightly counter-intuitive in that the independent variable (in the denominator) describes the effect and the dependent variable (in the numerator) the initial condition. The differential cross section is always taken to be positive, even though in the most frequent case of limited-range repulsive interactions, larger impact parameters cause less deflection. In rotationally symmetric problems, the azimuthal angle  is not changed by the scattering process, and the differential cross section becomes

is not changed by the scattering process, and the differential cross section becomes

,

,

where  is the angle between the incident and exit direction of the scattered particle, as shown in the figure.

is the angle between the incident and exit direction of the scattered particle, as shown in the figure.

Quantum scattering

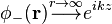

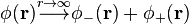

In time-independent formalism of quantum scattering, the initial wave function (before scattering) is taken to be a plane wave with definite momentum k:

where z and r) are the relative coordinates between the projectile and the target. The arrow indicates that this only describes the asymptotic behavior of the wave function when the projectile and target are too far apart for the interaction to have any effect.

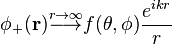

After the scattering takes place, it is expected that the wave function takes on the following asymptotic form:

where f is some function of the angular coordinates known as the scattering amplitude. This general form is valid for any short-ranged, energy-conserving interaction. It is not true for long-ranged interactions, so there are additional complications when dealing with electromagnetic interactions.

The full wave function of the system behaves asymptotically as the sum,

.

.

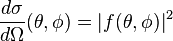

The differential cross section is related to the scattering amplitude:

This has the simple interpretation as the probability of finding the scattered projectile within a given solid angle.

A cross section is therefore a measure of the effective surface area seen by the impinging particles, and as such is expressed in units of area. The cross section of two particles (i.e. observed when the two particles are colliding with each other) is a measure of the interaction event between the two particles. The cross section is proportional to the probability that an interaction will occur; for example in a simple scattering experiment the number of particles scattered per unit of time (current of scattered particles  ) depends only on the number of incident particles per unit of time (current of incident particles

) depends only on the number of incident particles per unit of time (current of incident particles  ), the characteristics of target (for example the number of particles per unit of surface N), and the type of interaction. For

), the characteristics of target (for example the number of particles per unit of surface N), and the type of interaction. For  we have

we have

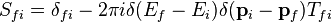

Relation to the S-matrix

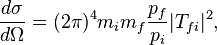

If the reduced masses and momenta of the colliding system are mi, pi and mf, pf before and after the collision respectively, the differential cross section is given by

where the on-shell T matrix is defined by

in terms of the S-matrix. Here,  is the Dirac delta function. The computation of the S-matrix is the main goal of the scattering theory.

is the Dirac delta function. The computation of the S-matrix is the main goal of the scattering theory.

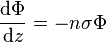

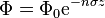

Attenuation

If a beam enters a thin layer of material of thickness dz, the flux of the beam Φ will decrease according to:

where σ is the total cross section of all events, including scattering, or to absorption, or transformation to another species. Solving this equation leads to the exponentially decaying behavior:

where Φ0 is the initial flux. For light, this is called the Beer–Lambert law.

This basic concept can then extended to the cases where the interaction probability in the targeted area assumes intermediate values, because the target itself is not homogeneous, or because the interaction is mediated by a non-uniform field.

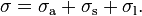

Scattering of light

In general, the scattering cross section is different from the geometrical cross section of a particle, and it depends upon the wavelength of light and the permittivity, shape and size of the particle. The total amount of scattering in a sparse medium is determined by the product of the scattering cross section and the number of particles present. In terms of area, the total cross section (σ) is the sum of the cross sections due to absorption, scattering and luminescence

The total cross-section is related to the absorbance of the light intensity through Beer–Lambert law, which says absorbance is proportional to concentration:

where Aλ is the absorbance at a given wavelength λ, C is the concentration as a number density, and  is the path length. The absorbance of the radiation is the logarithm (decadic or, more usually, natural) of the reciprocal of the transmittance:[2]

is the path length. The absorbance of the radiation is the logarithm (decadic or, more usually, natural) of the reciprocal of the transmittance:[2]

Scattering of light on extended bodies

In the context of scattering light on extended bodies, the scattering cross-section, σscat, describes the likelihood of light being scattered by a macroscopic particle. In general, the scattering cross-section is different from the geometrical cross-section of a particle as it depends upon the wavelength of light and the permittivity in addition to the shape and size of the particle. The total amount of scattering in a sparse medium is determined by the product of the scattering cross-section and the number of particles present. In terms of area, the total cross-section (σ) is the sum of the cross-sections due to absorption, scattering and luminescence

The total cross-section is related to the absorbance of the light intensity through Beer-Lambert's law, which says absorbance is proportional to concentration:  , where Aλ is the absorbance at a given wavelength λ, C is the concentration as a number density, and l is the path length. The extinction or absorbance of the radiation is the logarithm (decadic or, more usually, natural) of the reciprocal of the transmittance:[3]

, where Aλ is the absorbance at a given wavelength λ, C is the concentration as a number density, and l is the path length. The extinction or absorbance of the radiation is the logarithm (decadic or, more usually, natural) of the reciprocal of the transmittance:[3]

Relation to physical size

There is no simple relationship between the scattering cross-section and the physical size of the particles, as the scattering cross-section depends on the wavelength of radiation used. This can be seen when driving in foggy weather: the droplets of water (which form the fog) scatter red light less than they scatter the shorter wavelengths present in white light, and the red rear fog light can be distinguished more clearly than the white headlights of an approaching vehicle. That is to say that the scattering cross-section of the water droplets is smaller for red light than for light of shorter wavelengths, even though the physical size of the particles is the same.

Meteorological range

The scattering cross-section is related to the meteorological range, LV:

The quantity C σscat is sometimes denoted bscat, the scattering coefficient per unit length.[4]

Applications

Differential and total scattering cross sections are among the most important measurable quantities in nuclear and particle physics. Instead of the solid angle, the momentum transfer may be used as the independent variable of differential cross sections.

Differential cross sections in inelastic scattering contain resonance peaks that indicate the creation of metastable states and contain information about their energy and lifetime.

The total cross section in inelastic scattering is the sum of the total cross sections of all allowed individual processes. As a consequence, total cross sections of the creation of hadrons (i.e., strongly interacting particles) receive a factor of 3 from the quarks' color symmetry, allowing scientists to discover this symmetry.

Examples

Example 1: elastic collision of two hard spheres

The elastic collision of two hard spheres is an instructive example that demonstrates the sense of calling this quantity a cross section.  and

and  are the radii of the scattering center and scattered sphere, respectively,

are the radii of the scattering center and scattered sphere, respectively,  the impact parameter and

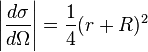

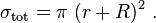

the impact parameter and  the polar angle of the exit trajectory as above. Then the differential scattering cross section is

the polar angle of the exit trajectory as above. Then the differential scattering cross section is

The total cross section is

So in this case the total scattering cross section is equal to the area of the circle (with radius  ) within which the center of mass of the incoming sphere has to arrive for it to be deflected, and outside which it passes by the stationary scattering center.

) within which the center of mass of the incoming sphere has to arrive for it to be deflected, and outside which it passes by the stationary scattering center.

Example 2: differential cross section for the geometric light scattering from the circle mirror

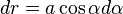

Another example illustrates the details of the calculation of a simple light scattering model obtained by a reduction of the dimension. For simplicity, we will consider the scattering of a beam of light on a plane treated as a uniform density of parallel rays and within the framework of geometrical optics from a circle with radius  with a perfectly reflecting boundary. Its three dimensional equivalent is therefore the more difficult problem of a laser or flashlight light scattering from the mirror sphere, for example from the mechanical bearing ball.[5] The unit of cross section in one dimension is the unit of length, e. g. one meter. Let

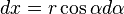

with a perfectly reflecting boundary. Its three dimensional equivalent is therefore the more difficult problem of a laser or flashlight light scattering from the mirror sphere, for example from the mechanical bearing ball.[5] The unit of cross section in one dimension is the unit of length, e. g. one meter. Let  be the angle between the light ray and the radius joining the reflection point of the light ray with the center point of the circle mirror. Then the increase of the length element perpendicular to the light beam is expressed by this angle as

be the angle between the light ray and the radius joining the reflection point of the light ray with the center point of the circle mirror. Then the increase of the length element perpendicular to the light beam is expressed by this angle as

the reflection angle of this ray with respect to the incoming ray is then  and the scattering angle is

and the scattering angle is

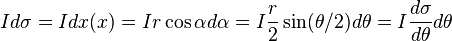

The energy or the number of photons reflected from the light beam with the intensity or density of photons  on the length

on the length  is

is

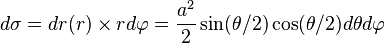

The differential cross section is therefore

As it is seen from the behaviour of the sine function this quantity has the maximum for the front backward scattering ( ) (the light is reflected perpendicularly and it returns) and the zero minimum for the scattering from the edge of the circle directly straight (

) (the light is reflected perpendicularly and it returns) and the zero minimum for the scattering from the edge of the circle directly straight ( ). It confirms the intuitive expectations that the mirror circle acts like a diverging lens and a thin beam is more diluted the closer it is from the edge defined with respect to the incoming direction. The total cross section can be obtained by summing (integrating) the differential section of the entire range of angles:

). It confirms the intuitive expectations that the mirror circle acts like a diverging lens and a thin beam is more diluted the closer it is from the edge defined with respect to the incoming direction. The total cross section can be obtained by summing (integrating) the differential section of the entire range of angles:

so it is equal as much as the circular mirror is totally screening the two-dimensional space for the beam of light. In three dimensions for the mirror ball with the radius  it is therefore equal

it is therefore equal  .

.

Example 3: differential cross section for the geometric light scattering from the perfectly spherical mirror

We can now use the result from the Example 2 to calculate the differential cross section for the light scattering from the perfectly reflecting sphere in three dimensions. Let us denote now the radius of the sphere as  . Let us parametrize the plane perpendicular to the incoming light beam by the cylindrical coordinates

. Let us parametrize the plane perpendicular to the incoming light beam by the cylindrical coordinates  and

and  . In any plane of the incoming and the reflected ray we can write now from the previous example:

. In any plane of the incoming and the reflected ray we can write now from the previous example:

while the impact area element is

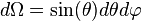

Using the relation for the solid angle in the spherical coordinates:

and the trigonometric identity:

we obtain

while the total cross section as we expected is

As one can see it also agrees with the result from the Example 1 while photon is assumed to be a rigid sphere of the zero radius.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 127–28, ISBN 92-822-2213-6

- ↑ Bajpai, P.K. "2. Spectrophotometry". Biological Instrumentation and Biology. ISBN 81-219-2633-5.

- ↑ Bajpai, P.K. "2. Spectrophotometry". Biological Instrumentation and Biology. ISBN 81-219-2633-5.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Scattering cross-section, σscat".

- ↑ M. Xu, R. R. Alfano (2003). "More on patterns in Mie scattering". Optics Communications 226: 1–5. Bibcode:2003OptCo.226....1X. doi:10.1016/j.optcom.2003.08.019.

Sources

- J.D.Bjorken, S.D.Drell, Relativistic Quantum Mechanics, 1964

- P.Roman, Introduction to Quantum Theory, 1969

- W.Greiner, J.Reinhardt, Quantum Electrodynamics, 1994

- R.G. Newton. Scattering Theory of Waves and Particles. McGraw Hill, 1966.

- R.C. Fernow (1989). Introduction to Experimental Particle Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-379-407.

External links

- Nuclear Cross Section

- Scattering Cross Section

- IAEA - Nuclear Data Services

- BNL - National Nuclear Data Center

- Particle Data Group - The Review of Particle Physics

- IUPAC Goldbook - Definition: Reaction Cross Section

- IUPAC Goldbook - Definition: Collision Cross Section