Saurophaganax

| Saurophaganax Temporal range: Late Jurassic, 150 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton, Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Carnosauria |

| Clade: | †Allosauria |

| Family: | †Allosauridae |

| Genus: | †Saurophaganax Chure, 1995 |

| Species: | † S. maximus |

| Binomial name | |

| Saurophaganax maximus (Stovall, 1950) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

"Saurophagus" maximus Stovall, 1950 (preoccupied) | |

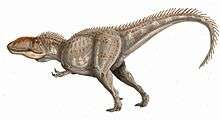

Saurophaganax ("lizard-eater") is a genus of allosaurid dinosaur from the Morrison Formation of Late Jurassic Oklahoma (latest Kimmeridgian age, about 151 million years ago), USA.[1] Some paleontologists consider it to be a species of Allosaurus (A. maximus). Saurophaganax represents a very large Morrison allosaurid characterized by horizontal laminae at the bases of the dorsal neural spines above the transverse processes, and "meat-chopper" chevrons.[2] The maximum size of S. maximus has been estimated at anywhere from 10.5 metres (34 ft)[3] to 13 m (43 ft) in length,[4] and around 3 tonnes (3.0 long tons; 3.3 short tons) in weight.[3]

Discovery and naming

In 1931 and 1932 John Willis Stovall uncovered remains of a large theropod near Kenton in Cimarron County, Oklahoma in layers of the late Kimmeridgian. In 1941 these were named Saurophagus maximus by Stovall in an article by journalist Grace Ernestine Ray.[5] The generic name is derived from Greek σαυρος, sauros, "lizard" and φάγειν, phagein, "to eat", with the compound meaning of "eater of saurians". The specific epithet maximus means "the largest" in Latin. Because the naming article did not contain a description, the name remained a nomen nudum. In 1950 Stovall described the finds.[6] However, in 1987 Spencer George Lucas e.a. concluded a lectotype had to be designated among the many bones: OMNH 4666, a tibia.[7]

Later it was discovered that the name Saurophagus was preoccupied: it had already in 1831 been given by William Swainson to a tyrant-flycatcher, a real eater of lizards.[8] In 1995 Daniel Chure named a new genus: Saurophaganax, adding Greek suffix -άναξ, anax, meaning "ruler", to the earlier name. Chure also established that the lectotype tibia was not diagnostic in relation to Allosaurus. He designated another element as the type specimen: OMNH 01123, a neural arch. This was not intended as a neotype of the old genus but as the holotype of a genus different from "Saurophagus". The type species Saurophaganax maximus, based on diagnostic material, is thus not to be considered conspecific with Saurophagus maximus based on an undiagnostic bone — which species Chure later stated to be a nomen dubium[9] — and Saurophaganax is not a renaming of "Saurophagus".[10] Much of the material previously referred to Saurophagus maximus, namely those diagnostic elements that could be distinguished from Allosaurus, were by Chure referred to Saurophaganax maximus. They contain disarticulated bones of at least four individuals.[10]

Saurophaganax is the official state fossil of Oklahoma,[11] and a large skeleton of Saurophaganax can be seen in the Jurassic hall in the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. Although the best known Saurophaganax material was found in the panhandle of Oklahoma, possible Saurophaganax material, NMMNH P-26083, a partial skeleton including a femur, several tail vertebrae, and a hip bone, has been found in northern New Mexico.

Relationship with Allosaurus

The identification of Saurophaganax is a matter of dispute. It has been described as its own genus,[10] or as a species of Allosaurus: Allosaurus maximus.[12] The most recent review of basal tetanurans accepted Saurophaganax as a distinct genus.[13] New possible Saurophaganax material from New Mexico may clear up the status of the genus.

Ecology

Saurophaganax was one of the largest carnivores of Late Jurassic North America. Chure even gave an estimate of 14 m (46 ft),[10] though other estimations have been lower. The fossils known of Saurophaganax (both the possible New Mexican material and the Oklahoma material) are known from the Brushy Basin Member, which is the latest part of the Morrison Formation, suggesting that this genus was either always uncommon or that it first appeared rather late in the Jurassic. Saurophaganax was large for an allosaurid, and bigger than both its contemporaries Torvosaurus tanneri and Allosaurus fragilis. Being much rarer than its contemporaries, making up one percent or less of the Morrison theropod fauna, not much about its behavior is known.

The Morrison Formation is a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments which, according to radiometric dating, ranges between 156.3 million years old (Ma) at its base,[14] to 146.8 million years old at the top,[15] which places it in the late Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian, and early Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic period. This formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet and dry seasons. The Morrison Basin where dinosaurs lived, stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was formed when the precursors to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west. The deposits from their east-facing drainage basins were carried by streams and rivers and deposited in swampy lowlands, lakes, river channels and floodplains.[16] This formation is similar in age to the Solnhofen Limestone Formation in Germany and the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania. In 1877 this formation became the center of the Bone Wars, a fossil-collecting rivalry between early paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs such as Barosaurus, Brontosaurus, Camarasaurus, Diplodocus, and Brachiosaurus. Dinosaurs that lived alongside Saurophaganax, and may have served as prey, included the herbivorous ornithischians Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Othnielosaurus. Predators in this paleoenvironment included the theropods Torvosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Marshosaurus, Stokesosaurus, Ornitholestes, and[17] Allosaurus, which accounted for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens and was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food web.[18] Other vertebrates that shared this paleoenvironment included ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphans, and several species of pterosaur. Early mammals were present in this region, such as docodonts, multituberculates, symmetrodonts, and triconodonts. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.[19] In Oklahoma, Stovall unearthed a considerable number of Apatosaurus specimens, which may have represented possible prey for a large theropod like Saurophaganax.

References

- ↑ Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999). "Biostratigraphy of dinosaurs in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior, U.S.A." Pp. 77–114 in Gillette, D.D. (ed.), Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1.

- ↑ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Saurophagus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 793–794. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- 1 2 Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 96

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

- ↑ Ray, G.E., 1941, "Big for his day", Natural History 48: 36-39

- ↑ Stovall, J.W. & Langston, W. Jr. (1950). "Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, a New Genus and Species of Lower Cretaceous Theropods From Oklahoma" (PDF). American Midland Naturalist 43 (3): 696–728. doi:10.2307/2421859.

- ↑ Lucas, S.G., Mateer, N.J., Hunt, A.P., and O'Neill, F.M., 1987, "Dinosaurs, the age of the Fruitland and Kirtland Formations, and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the San Juan Basin, New Mexico", p. 35-50. In: Fassett, J.E. and Rigby, J.K., Jr. (eds.), The Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the San Juan and Raton Basins, New Mexico and Colorado. GSA Special Paper 209

- ↑ W. Swainson and J. Richardson, 1831, Fauna boreali-americana, or, The zoology of the northern parts of British America : containing descriptions of the objects of natural history collected on the late northern land expeditions under command of Captain Sir John Franklin, R.N. Part 2, Birds, London, J. Murray

- ↑ Chure, D., 2000, A new species of Allosaurus from the Morrison Formation of Dinosaur National Monument (Utah-Colorado) and a revision of the theropod family Allosauridae. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, pp. 1-964

- 1 2 3 4 Chure, Daniel J. (1995). "A reassessment of the gigantic theropod Saurophagus maximus from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Oklahoma, USA". In A. Sun and Y. Wang (eds.). Sixth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Short Papers. Beijing: China Ocean Press. pp. 103–106.

- ↑ "OK State Symbols". OkInsider.com. Oklahoma Publishing Today. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ↑ Smith, David K. (1998). "A morphometric analysis of Allosaurus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 18 (1): 126–142. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011039.

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Molnar, Ralph E.; Currie, Philip J. (2004). Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.), ed. The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 71–110. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs 38 (6): 7.

- ↑ Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry - age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; and Kirkland, J.I. (eds.). The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120. ISSN 0026-7775.

- ↑ Russell, Dale A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- ↑ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ↑ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; and Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

Sources

- Dixon, Dougal. The World Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures.

| Wikispecies has information related to: Saurophaganax |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||