Sarah A. Bowman

Sarah A. Bowman (c. 1813 – December 22, 1866) was an American innkeeper, restaurateur, and madam. Nicknamed "The Great Western", she gained fame, and the title "Heroine of Fort Brown", as a camp follower of Zachary Taylor's army during the Mexican–American War. Following the war she operated an inn in Franklin, Texas (now El Paso) before settling near Arizona City (now Yuma, Arizona). Over the course of her life she was married multiple times, often without legal record or the blessing of a priest, and was known at various times by the names Boginnis, Bourdette, Bourget, Bourjette, Borginnis, Davis, Bowman, and possibly Foyle.[1]

Background

Bowman is believed to have been born Sarah Knight sometime between 1812 and 1813 (the 1860 census indicates her birth may have occurred as late as 1818[2]) in either Tennessee or Clay County, Missouri. Raised on the American frontier, she received no formal education, and is believed to have been illiterate due to her use of an X on business and census forms.[3] Despite the inability to read and write, she was bilingual by her later years, with a priest near Fort Yuma noting she was the first American woman he had met fluent in Spanish.[4]

Physically, Bowman was an unusually large woman. Standing 6 feet (1.8 m) tall (some reports claim 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m)) and reportedly weighing 200 pounds (91 kg), she was described as "a remarkably large, well-proportioned strong woman, of strong nerves, and great physical power."[5] Other observers noted she had an hourglass figure. Due to her large size she was nicknamed the Great Western, an apparent reference to SS Great Western, for a time the largest ship afloat.[6] Bowman also possessed skills to complement her Amazon-like physique. Texas Ranger John Salmon Ford said of her, "She could whip any man, fair fight or foul, could shoot a pistol better than anyone in the region, and at black jack could outplay (or out cheat) the slickest professional gambler."[7]

Several tales are told of Bowman and her earlier years. The first is that she and her husband had accompanied Zachary Taylor during his campaign during the Seminole Wars.[8] There is no record of a woman matching Bowman's description accompanying Taylor, but such an event would help explain her later loyalty to him.[9] A second tale claims Bowman was in love with Taylor. If this is true, there is no evidence the affection was returned.[10]

Mexican–American War

The first documented record of Bowman occurs in 1845 at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. When her husband enlisted in the Seventh infantry, she signed on as a laundress, a position that included food, shelter, and the opportunity to earn a salary three times that earned by an Army private.[1] From Jefferson Barracks she accompanied the army to Corpus Christi Bay. By the time the army arrived in July 1845, her duties included cook and nurse in addition to the laundry.[11]

The army remained encamped along the Nueces River till March 1846 when they received orders to advance to the Rio Grande. Instead of following her husband, who was ill, and most of the military wives on ships down the coast, Bowman purchased a wagon and mule team and followed the army on land.[12] She handled the trek with skills the "best teamster in the train might have envied."[5]

The first encounter between American and Mexican forces came on March 21, 1846 during the crossing of Arroyo Colorado.[10] As the Americans approached the steep embankment, bugles rang out on the other bank accompanied by the warning, "Cross this stream and you will be shot!"[12] Upon seeing the column halted, Bowman rode to the front and told the commander, "If the general would give me a strong pair of tongs, I'd wade that river and whip every scoundrel that dared show himself."[3] (In addition to the tool, tongs was at the time slang for men's trousers.[13]) Inspired by her example the American troops made the crossing, scattering the opposing troops in the process.[3]

Heroine of Fort Brown

By May 1846, Bowman was married to her second husband, a man named Borginnes (spellings vary). Her husband was assigned to Fort Texas (later renamed Fort Brown) where she operated an officer's mess. When Taylor withdrew the majority of his troops to confront the Mexican army near the coast, forces in Matamoros, stationed directly across the Rio Grande, responded by besieging the fort.[6]

The Mexican bombardment began May 3 at 5 am. While most of the women in the fort retreated to the bunkers to sew sandbags, Borginnes remained at her cooking fire and served breakfast at 7 am.[14] For the next week she prepared food and coffee for the besieged fort, carrying buckets of coffee to the troops manning the fort's guns, even finding time to care for the wounded and other women.[6] Her schedule of three meals daily was continued even though bullets struck both her bonnet and bread tray.[5] She also requisitioned a musket in case the fort was stormed.[15]

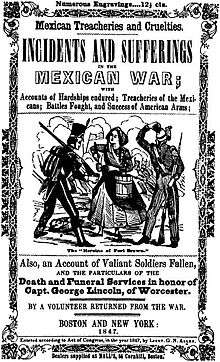

Following the siege, Borginnes came to the attention of U.S. newspapers who named her the "Heroine of Fort Brown".[6] Stories of her exploits were published in both Philadelphia and New York City. One correspondent even went out of his way to extol her virtues and fight any "tongues of slander" that might be directed at her character.[5]

Battle of Buena Vista

Following Fort Brown, Borginnes briefly established a boarding house called the American House in Matamoros. In addition to food, lodging, and stables for soldiers' horses, the establishment also served as a saloon and brothel. This establishment proved quite popular, with one soldier describing it as "the headquarters for everyone".[16] As Taylor's force moved into Mexico the American House moved with the army, first to Monterrey and then to Saltillo.[17]

While Borginnes was not involved in the Battle of Monterrey, she did see action during the Battle of Buena Vista. During the conflict she prepared food and coffee, reloaded weapons, and carried wounded off the field of battle.[18] Her attention to the injured even earned her the nickname "Doctor Mary".[17] Legend claims she received a saber wound to her cheek while working a cannon position before slaying the Mexican soldier who cut her.[19] Another incident involves a retreating private. The soldier ran into Borginnes' restaurant yelling that Taylor had been defeated. She responded by punching the private in the face and telling him "You damned son of a bitch, there ain't Mexicans enough in Mexico to whip old Taylor. You just spread that report and I'll beat you to death."[4]

During the battle Borginnes learned that Captain George Lincoln, a friend that had joined the army at the same time as her husband, had been killed. Not wishing to have his body stripped, she searched for him during the battle. Upon finding him, she brought the body back to Saltillo and made sure he was properly buried.[6][17] After the battle she purchased Lincoln's horse at auction, beating a $75 bid with a $200 offer, and made arrangements for the horse to be sent to the captain's family.[20]

Following her actions upon the field of battle, tradition maintains that General Winfield Scott ordered a military pension for Borginnes.[21]

Later life

Following the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the U.S. Army prepared to depart Northern Mexico. By this time Borginnes' second husband had left her—whether by death or abandonment is unknown. She wished to accompany the departing troops to California, but was informed that only military wives were allowed to join the column.[22] In response she mounted her horse, rode through the soldiers, and shouted "Who wants a wife with $15,000 and the biggest leg in Mexico! Come, my beauties, don't all speak at once—who is the lucky man?"[23] Eventually a dragoon named either Davis or David E. volunteered, on condition that a priest perform the marriage ceremony.[22] Her response to this was, "Bring your blanket to my tent tonight and I will learn you to tie a knot that will satisfy you, I reckon!"[23]

By early 1849, following a brief illness, the "Great Western" arrived in Franklin (now El Paso, Texas) without a husband and again using her second husband's name.[23] There she established an inn that catered to people traveling across the country as part of the California Gold Rush. In the process she became known as El Paso's first Anglo woman and the town's first madam, gaining a reputation as a "whore with a heart of gold".[4][6]

By early 1850, Borginnes had moved up the Rio Grande to the town of Socorro. There she lived with a man named Juan Duran and five girls, possibly orphans, with the last name of Skinner. Shortly thereafter she married Alfred J. Bowman, a dragoon in the U.S. Army. Following his discharge on November 30, 1850 the couple moved west.[4]

Fort Yuma

Bowman arrived at Yuma Crossing in 1852.[24] Yuma's first business operator, she cooked and did laundry for the officers of Fort Yuma while her husband prospected.[25][24] One of the fort's soldiers noted, "She has been with the Army twenty years and was brought up here where she keeps the officer's mess. Among her other good qualities she is an admirable `pimp'. She used to be a splendid-looking woman and has done good service but is too old for that now."[26]

After a time Bowman opened a hotel near the fort, along with other businesses near Fort Buchanan and Patagonia, Arizona.[24][26][27] In addition to her business interests, she adopted a number of Mexican and Indian children.[28]

Bowman died December 22, 1866 from a spider bite.[2] Following her death she was breveted an honorary colonel and buried with military honors in the Fort Yuma cemetery.[27][29] In 1890, following the decommissioning of Fort Yuma, she was exhumed and reburied at San Francisco National Cemetery in a grave marked "Sarah A. Bowman".[30][24]

In 1998, the events of Bowman's life were used as the basis for the historical fiction Fearless, A Novel of Sarah Bowman.[31] She also features under the name Sarah Borginnis in Cormac McCarthy's epic Western Blood Meridian, and a fictionalized version of "The Great Western" appears in Larry McMurtry's novel Dead Man's Walk

References

- 1 2 Ledbetter 2006, p. 72.

- 1 2 Graf, Mercedes (September 22, 2001). "Standing tall with Sarah Bowman: the Amazon of the Border". Minerva: Quarterly Report on Women and the Military.

- 1 2 3 Anderson 2002, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Blevins 2008, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Johannsen 1985, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carletta 2006, p. 72.

- ↑ Blevins 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Blevins 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ Anderson 2002, pp. 2-3.

- 1 2 Blevins 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Ledbetter 2006, p. 73.

- 1 2 Anderson 2002, p. 1.

- ↑ Ledbetter 2006, p. 74.

- ↑ Anderson 2002, p. 3.

- ↑ Blevins 2008, p. 19.

- ↑ Anderson 2002, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Blevins 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Anderson 2002, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Ledbetter 2006, p. 77.

- ↑ Anderson 2002, p. 5.

- ↑ Johannsen 1985, p. 141.

- 1 2 Blevins 2008, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Anderson 2002, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Crowe, Rosalie Robles (September 2, 2007). "Yuma anytime". Arizona Daily Star.

- ↑ Carletta 2006, pp. 72-3.

- 1 2 Ledbetter 2006, p. 78.

- 1 2 Blevins 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Anderson 2002, p. 8.

- ↑

- "Sarah Bowman Lived a Life Deserving of Her Burial". Mohave Daily Miner. June 16, 1985.

- ↑ Carletta 2006, p. 73.

- ↑

- Patterson, Karen (September 13, 1998). "Bowman won't be penned down". Dallas Morning News.

- Anderson, Greta (2002). More than Petticoats: Remarkable Texas Women. Guilford, Conn.: TwoDot. ISBN 978-0-7627-1273-1.

- Blevins, Don (2008). A priest, a prostitute, and some other early Texans. Guilford, Conn.: TwoDot. ISBN 978-0-7627-4589-0.

- Carletta, David M. (2006). "Borginis, Sarah". In Bernard A. Cook (Ed.). Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present. ABC-CLIO. pp. 72–3. ISBN 978-1-85109-770-8.

- Johannsen, Robert W. (1985). To the Halls of the Montezumas. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504981-7.

- Ledbetter, Suzann (2006). Shady Ladies: Nineteen Surprising and Rebellious American Women. New York: Forge Books. ISBN 978-0-7653-0827-6.

External links

- Bowman, Sarah, Handbook of Texas

- Phillips, Lisa; Martinez, Reyna (1999–2000). Contributions by Amanda Mond and Giesel Toyosima. "Sarah Bowman and Tillie Howard: Madams of the 1800s". Borderlands (El Paso Community College) 18: 15.

|