Sans-serif

| |

Sans-serif font |

|

Serif font |

|

Serif font (serifs in red) |

In typography, a sans-serif, sans serif, gothic, san serif or simply sans typeface is one that does not have the small projecting features called "serifs" at the end of strokes.[1] The term comes from the French word sans, meaning "without" and "serif" from the Dutch word schreef meaning "line". Sans-serif fonts tend to have less line width variation than serif fonts.

In print, sans-serif fonts are often used for headlines rather than for body text.[2]

Sans-serif fonts have become the most prevalent for display of text on computer screens. This is partly because interlaced screens have shown twittering on the fine details of the horizontal serifs. Additionally, on lower-resolution digital displays, fine details like serifs may disappear or appear too large.

Before the term "sans-serif" became common in English typography, a number of other terms had been used. One of these outmoded terms for sans serif was gothic, which is still used in East Asian typography and sometimes seen in font names like Century Gothic, Highway Gothic, or Trade Gothic.

Sans-serif fonts are sometimes, especially in older documents, used as a device for emphasis, due to their typically blacker type color.

History

The first sans-serif types were developed in the 18th century. They became popular in printed media in the early 19th century, at first under the term grotesque, as the omission of serifs was a significant departure from hundreds of years of tradition in printed text.[3] The term 'grotesque' comes from Italian for cave, and was often used to describe Roman decorative styles found by excavation, but had long become applied in the modern sense for objects that appeared 'malformed or monstrous'.[4]

Letters without serifs historically appear in epigraphy, especially in casual, non-monumental epigraphy (while serifs were developed for monumental inscriptions in Roman capitals in the Roman imperial era). The earliest typesets which omitted serifs were not intended to render contemporary texts, but to represent ancient inscriptions. Thus, Thomas Dempster's De Etruria regali libri VII (1723), used special types intended for the representation of Etruscan epigraphy, and in c. 1745, Caslon foundry made Etruscan types for pamphlets written by Etruscan scholar John Swinton.[5]

In late 18th century, Neoclassicism led to architects increasingly incorporating ancient Greek and Roman designs in contemporary structures. Among the architects, John Soane was noted for using sans-serif letters on his drawings and architectural designs, which were eventually adopted by other designers, such as Thomas Banks and John Flaxman.

In 1786 a rounded sans-serif font that was developed by Valentin Haüy first appeared in the book titled "Essai sur l'éducation des aveugles" (An Essay on the Education of the Blind).[6] The purpose of this font was to be invisible and address accessibility. It was designed to emboss paper and allow the blind to read with their fingers.[7] The design was eventually known as Haüy type.[8]

Sans-serif letters began to appear in printed media as early as 1805, in European Magazine. However, early-19th-century commercial sign writers and engravers had modified the sans-serif styles of neoclassical designers to include the uneven stroke weights found in serif Roman fonts, producing sans-serif letters.[9]

In London, 'Egyptian' lettering was popular for advertising, apparently because of the "astonishing" effect the unusual style had on the public.[10]

In 1816, the Ordnance Survey began to use 'Egyptian' type, which was printed using copper plate engraving of monoline sans-serif capital letters, to name ancient Roman sites.[9]

In 1816, William Caslon IV produced the first sans-serif printing type in England for Latin characters under the title 'Two Lines English Egyptian', where 'Two Lines English' referred to the font's body size, which equals to about 28 points.[11] Originally cut in 1812.[12]

Sans-serifs were popular due to their clarity and legibility at distance in advertising and display use, when printed very large or very small. Much early sans-serif signage was not actually printed but hand-painted, carved lettered, since large signs were difficult to print but could easily be painted by hand. (This makes tracing the descent of sans-serif styles hard, since a trend can arrive in the printed record from a signpainting tradition which has left less of a record.) Because sans-serif type was often used for headings and commercial printing, many early sans-serif designs did not feature lower-case letters. Simple sans-serif capitals, without use of lower-case, became very common on tombstones of the Victorian period in Britain.

The first Grotesque typeface complete with lower-case letters was probably cast by the Schelter & Giesecke Foundry as early as 1825.[13]

The term sans-serif was first employed in 1832 by Vincent Figgins.[14]

The first use of sans serif as a running text is believed to be the short booklet Feste des Lebens und der Kunst: eine Betrachtung des Theaters als höchsten Kultursymbols (Celebration of Life and Art: A Consideration of the Theater as the Highest Symbol of a Culture),[15] by Peter Behrens, in 1900.[16]

Throughout the nineteenth century sans-serif types were viewed with suspicion by printers of fine books as being fit only for advertisements (if that), and to this day most books remain printed in serif fonts as body text.[17] This impression would not have been helped by the standard of common sans-serif types of the period, many of which now seem somewhat lumpy and eccentrically-shaped. As late as 1922, master printer Daniel Berkeley Updike described sans-serif fonts as having "no place in any artistically respectable composing-room."[18] By 1937 he stated that he saw no need to change this opinion in general, though he felt that Gill Sans and Futura were the best choices if sans-serifs had to be used.[19]

Through the early twentieth century, an increase in popularity of sans-serif fonts took place as more artistic and complex designs were created. As Updike's comments suggest, the more constructed humanist and geometric sans-serif designs were viewed as increasingly respectable, and were shrewdly marketed in Europe and America as embodying classic proportions (with influences of Roman capitals) while presenting a spare, modern image.[20][21][22][23] While he disliked sans-serif fonts in general, the American printer J.L Frazier wrote of Copperplate Gothic in 1925 that "a certain dignity of effect accompanies...due to the absence of anything in the way of frills," making it a popular choice for the stationery of professionals such as lawyers and doctors.[24] By the mid-century, neo-grotesque fonts such as Univers and Helvetica had become popular through offering a more unified range of styles than on previous designs, allowing a wider range of text to be set artistically through setting headings and body text in a single font.[25][26][27][28][29]

Other names for sans-serif

Early appellatives

- Egyptian: The term was first used by Joseph Farington after seeing the sans serif inscription on John Flaxman's memorial to Isaac Hawkins Brown in 1805,[9] though today the term is commonly used to refer to slab serif, not sans serif.

- Antique: In about 1817, the Figgins foundry in London made a type with square or slab-serifs which it called 'Antique', and that name was adopted by most of the British and US typefounders. An exception was the typefounder Thorne, who confused things by marketing his Antique under the name 'Egyptian'. In France it became Egyptienne, and to worsen the confusion, the French called sans-serif type 'Antique'.[5] Some fonts, such as Antique Olive, still carry the name.

- Grotesque: It was originally coined by William Thorowgood of Fann Street Foundry in 1832.[13] The name came from the Italian word 'grottesco', meaning 'belonging to the cave'. In Germany, the name became Grotesk. German typefounders adopted the term from the nomenclature of Fann Street Foundry, which took on the meaning of cave (or grotto) art.[31] Nevertheless, some explained the term was derived from the surprised response from the typographers.

- Doric: It was the term first used by H. W. Caslon Foundry in Chiswell Street in 1870 to describe various sans-serif fonts at a time the generic name 'sans-serif' was commonly accepted. Eventually the foundry used Sans-serif in 1906. At that time, Doric referred to a certain kind of stressed sans-serif types.

- Gothic: Not to be confused with blackletter typeface, the term was used mainly by American type founders. Perhaps the first use of the term was due to the Boston Type and Stereotype Foundry, which in 1837 published a set of non-serifed typefaces under that name. It is believed that those were the first sans serif designs to be introduced in America.[32] The term probably derived from the architectural definition, which is neither Greek nor Roman,[33] and from the extended adjective term of "Germany", which was the place where sans-serif typefaces became popular in 19th to 20th century.[34] Early adopters for the term includes Miller & Richard (1863), J. & R. M. Wood (1865), Lothian, Conner, Bruce McKellar. Although the usage is now rare in the English-speaking world, the term is commonly used in Japan and South Korea; in China they are known by the term heiti (Chinese: 黑體), literally meaning "black type", which is probably derived from the mistranslation of Gothic as blackletter typeface, even though actual blackletter fonts have serifs.

Recent appellatives

- Lineale, or linear: The term was defined by typographic historian Maximilien Vox in the VOX-ATypI classification to describe sans-serif types. Later, in British Standards Classification of Typefaces (BS 2961:1967), lineale replaced sans-serif as classification name.

- Simplices: In Jean Alessandrini's désignations préliminaries (preliminary designations), simplices (plain typefaces) is used to describe sans-serif on the basis that the name 'lineal' refers to lines, whereas, in reality, all typefaces are made of lines, including those that are not lineals.[35]

- Swiss: It is used as a synonym to sans-serif, as opposed to roman (serif). The OpenDocument format (ISO/IEC 26300:2006) and Rich Text Format can use it to specify the sans-serif generic font family name for a font used in a document.[36][37][38] Presumably refers to the popularity of sans-serif grotesque and neo-grotesque types in Switzerland.

Classification

For the purposes of type classification, sans-serif designs are usually divided into three or four major groups, the fourth being the result of splitting the grotesque category into grotesque and neo-grotesque.[39][40]

Grotesque

This group features the early (19th century to early 20th) sans-serif designs. Influenced by Didone serif fonts of the period and signpainting, these were often quite solid, bold designs suitable for headlines and advertisements. Many did not feature a lower case or italics, since they were not needed for such uses. They were sometimes released by width, with a range of widths from extended to normal to condensed, with each style different, meaning to modern eyes they can look quite irregular and eccentric.[25][41] Grotesque fonts have a vertical axis and limited variation of stroke width (often none perceptible in capitals). The terminals of curves are usually horizontal, and many have a spurred "G" and an "R" with a curled leg. Capitals tend to fit within a square in the regular width. Cap height and ascender height are generally the same to create a more regular effect in texts such as titles with many capital letters, and descenders are often short for tighter linespacing.[4] Most avoid having a true italic in favour of a more restrained oblique or sloped design, although at least some did have true italics.[30]

Examples of grotesque fonts include Akzidenz Grotesk, News Gothic, Franklin Gothic and Monotype Grotesque, though some digital releases of these reduce their eccentricities in order to make them more suitable to modern tastes. Akzidenz Grotesk Old Face, Knockout by Hoefler & Frere-Jones and Monotype Grotesque are examples of digital fonts that retain the characteristics of early sans-serif types.[42][43][44][45] The term realist has also been applied to these designs due to their practicality and simplicity.

Neo-grotesque

As the name implies, these modern designs consist of a direct evolution of grotesque types. They are relatively straightforward in appearance with limited width variation. Unlike earlier grotesque designs, many were issued in extremely large and versatile families from the time of release, making them easier to use for body text.

The story of neo-grotesque types began in the 1950s with the emergence of the International Typographic Style, or Swiss style. Its members looked at the clear lines of Akzidenz Grotesk (1896) as an inspiration to create rational, almost neutral typefaces. In 1957 the release of Helvetica, Univers, and Folio, the first typefaces categorized as neo-grotesque, had a strong impact internationally: Helvetica came to be the most used typeface for the following decades.[46]

Other examples include: Rail Alphabet, Highway Gothic, Arial, Bell Centennial, MS Sans Serif, Acumin, San Francisco and Roboto.

Like some grotesque typefaces, neogrotesques often feature a 'folded-up' design, in which strokes (for example on the 'c') are curved all the way round to end on a perfect horizontal or vertical. Helvetica is an example of this. Others such as Arial are less regular.

Geometric

As their name suggests, Geometric sans-serif typefaces are based on geometric shapes, like near-perfect circle and square. Note the optically circular letter "O" and the simple construction of the lowercase letter "a". Of these four categories, geometric fonts tend to be the least useful for body text.

The geometric sans is strongly associated with the Bauhaus art school (1919-1933).[47] Two early efforts in designing geometric types were made by Herbert Bayer and Jakob Erbar, who worked respectively on Universal Typeface (unreleased at the time but revived digitally as Architype Bayer) and Erbar (circa 1925). In 1927 Futura, by Paul Renner, was released to great acclaim and popularity.[48] Geometric sans-serif fonts were popular from the 1920s and 30s due to their clean, modern design, and many new geometric designs and revivals have been created since. A separate inspiration for many geometric types has been the simplified shapes of letters engraved or stencilled on metal and plastic in industrial use, which often follow a simplified geometric design.

Notable geometric types include Kabel, Nobel, ITC Avant Garde, Century Gothic, Gotham, Avenir, URW Grotesk and Drogowskaz. Designs considered geometric in style but which are less descended from the Futura/Erbar/Kabel tradition include Bank Gothic, DIN 1451, Eurostile and Handel Gothic.

Humanist

These are the most calligraphic of the sans-serif typefaces. Many take extensive inspiration from serif fonts, with true italics rather than an oblique, ligatures and even swashes in italic.

One of the earliest humanist designs was Johnston (Edward Johnston, 1916), and, a decade later, Gill Sans (Eric Gill, 1928).[49] Edward Johnston, a calligrapher by profession, was inspired by classic letter forms, with capitals based on roman inscriptions.

Humanist designs vary more than gothic or geometric designs.[50] Some humanist designs have stroke modulation (strokes that clearly vary in width along their line) or alternating thick and thin strokes. These include Lydian, Stellar, Rotis SemiSans, and most popularly Hermann Zapf's Optima (1958), a typeface expressly designed to be suitable for both display and body text.[51] Some humanist designs may be more geometric, as in Gill Sans and Johnston (especially their capitals), which like Roman capitals are often based on perfect squares, half-squares and circles. These somewhat architectural designs may feel too stiff for body text.[49] Others such as Syntax, Goudy Sans and Sassoon Sans more resemble handwriting, serif fonts or calligraphy.

Frutiger, from 1976, has been particularly influential in the development of the modern humanist sans genre, especially designs intended to be particularly legible above all other design considerations. The category expanded greatly during the 1980s and 1990s, partly as a reaction against the overwhelming popularity of Helvetica and Univers and also due to the need for legible fonts on low-resolution computer displays.[52][53][54][55] Designs from this period intended for print use include FF Meta, Myriad, Thesis, Charlotte Sans and Scala Sans, while designs created for computer use include Microsoft's Tahoma, Trebuchet, Verdana, Calibri and Corbel, as well as Lucida Grande, Fira Sans and Droid Sans. Humanist sans-serif designs can (if appropriately proportioned and spaced) be particularly suitable for use on screen or at distance, since their designs can be given wide apertures or separation between strokes, which is not a conventional feature on grotesque and neo-grotesque designs.

Other/mixed

Due to the diversity of sans-serif typefaces, many do not fit neatly into the above categories. For example, Neuzeit S has both neo-grotesque and geometric influences, as does Herman Zapf's URW Grotesk, while Klavika blends humanist and geometric influences.

A particular subgenre of sans-serifs is those with stroke contrast, which have been called 'modulated' sans-serifs. They are nowadays often placed within the humanist genre, although they predate Johnston which started the modern humanist genre. These may take inspiration from calligraphy or painted lettering, grotesque or humanist fonts.[56] In addition, many capitals-only sans-serifs of the nineteenth century have a naturally geometric design, but are classified in the grotesque genre.

Sans-serif analogues in non-Latin scripts

The concept of a typeface without traditional flourishes spread from the Western European typographical tradition to other scripts in the late 19th century. Like their Latin counterparts, non-Latin linear faces are popular for on-screen text due to their legibility. Sans-serif analogues are in common use for Greek, Cyrillic, Hebrew, and Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. See also East Asian sans-serif typeface.

Gallery

This gallery presents images of sans-serif font use across different times and places from early to recent. Particular attention is given to unusual uses and more obscure fonts, meaning this gallery should not be considered a representative sampling.

-

Sample use of early sans-serifs, Dublin 1848. Setting is caps only for titling, with the letters very bold and condensed. Reasonably conventional except for the crossed V-form 'W'.

-

Light sans-serif being used for body text. Germany, 1914

-

Capitals on a German propaganda poster, 1914.

-

Condensed but somewhat decorative sans-serif with small flourishes on the 'v' and 'e'. Ljubljana, 1916.

-

_Plakat_4._Kriegsanleihe_1916.jpg)

A conventional, nearly monoline sans combined with a stroke-modulated sans used for the title. German war bond poster, 1916.

-

Broad block capitals. Hungarian film poster, 1918.

-

A monoline sans-serif with art-nouveau influences visible in the tilted 'e' and 'a'. Note embedded umlaut at top left: accents are often compressed in sans-serif capitals as here to allow tight linespacing. Commemoration of Jewish soldiers killed fighting for Germany, 1920.

-

Thick block sans-serif capitals, with inner details kept very thin and narrow lines down the centres of letters, characteristic of Art Deco lettering. France, 1920s.

-

Thick sans-serif with shortened descenders, allowing tight linespacing. Switzerland, 1928.

-

Simple Geometric-style sans (the line 'O Governo do Estado', Brazil, 1930. Curves are kept to a minimum.

-

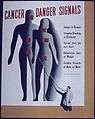

.jpg)

Lightly modulated sans serif lettering on a 1930s poster.

-

Classic geometric sans-serif capitals, 1934, Australia. Note the sharp points on the capital 'A' and 'N'.

-

Dwiggins' Metrolite and Metroblack fonts, geometric types of the style popular in the 1930s.

-

Lettering in relief, suggesting solid lettering on a wall. Sweden, 1942.

-

Modernist setting on a 1940s American poster. The curve of the 'r' is a common feature in grotesque fonts, but the 'single-story' 'a' is a classic feature of geometric fonts from the 1920s onwards.

-

Neo-grotesque type, 1972, Switzerland: Helvetica or a close copy. The tight setting is characteristic of the International style of graphic design. The irregular setting may have been the result of using transfers.

-

Irregular letters suggesting cut-out paper. Vietnam AIDS awareness poster, 1995.

-

Use of an irregular sans-serif. Example of the irregular 'grunge typography' movement of the 1990s; note irregular letters with no capitals.[1]

-

Swiss TV logo: tightly-spaced neo-grotesque capitals with a more rounded sans-serif on the left.

- ^ Shetty, Sharan. "The Rise And Fall Of Grunge Typography". The Awl. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

See also

- List of sans serif typefaces

- Serif

- East Asian sans-serif typeface

- Roman type

- Italic type

- Monospace

- Emphasis (typography)

- San Serriffe, an April fool joke by Guardian newspaper.

References

- ↑ "sans serif" in The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 10, p. 421.

- ↑ Serifs more used for headlines

- ↑ Tam, Keith (2002). Calligraphic tendencies in the development of sanserif types in the twentieth century (PDF). Reading: University of Reading (MA thesis).

- 1 2 Berry, John. "A Neo-Grotesque Heritage". Adobe Systems. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- 1 2 Mosley, James (January 6, 2007), The Nymph and the Grot, an update, archived from the original on June 10, 2014, retrieved June 10, 2014

- ↑ The First Book for Blind People

- ↑ Does your font choice measure up?

- ↑ How Braille Began

- 1 2 3 James Mosley, The Nymph and the Grot: the revival of the sanserif letter, London: Friends of the St Bride Printing Library, 1999

- ↑ "It became clear that in 1805 Egyptian letters were happening in the streets of London, being plastered over shops and on walls by signwriters, and they were astonishing the public, who had never seen letters like them and were not sure they wanted to." Mosley, James, The Nymph and the Grot, an update , 6 January 2007.

- ↑ Tracy, Walter (2003). Letters of credit : a view of type design. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 9781567922400.

- ↑ William Caslon IV's sans serif

- 1 2 Lawson 1990, p. 296.

- ↑ Meggs 2011, p. 149.

- ↑ Behrens, Peter (1900), Feste des Lebens und der Kunst: eine Betrachtung des Theaters als höchsten Kultursymbols (in German), Eugen Diederichs

- ↑ Meggs 2011, p. 242.

- ↑ Rogers, Updike, McCutcheon (1939). The work of Bruce Rogers, jack of all trades, master of one : a catalogue of an exhibition arranged by the American Institute of Graphic Arts and the Grolier Club of New York. New York: Grolier Club, Oxford University Press. pp. xxxv–xxxvii.

- ↑ Updike, Daniel Berkeley (1922). Printing types : their history, forms, and use; a study in survivals vol 2 (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 243. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ Lawson, Alexander (1990). Anatomy of a typeface (1st ed.). Boston: Godine. p. 330. ISBN 9780879233334.

- ↑ "Fifty Years of Typecutting" (PDF). Monotype Recorder 39 (2): 11, 21. 1950. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ "Gill Sans Promotional Poster, 1928". Red List. Monotype.

- ↑ Robinson, Edwin (1939). "Preparing a Railway Timetable" (PDF). Monotype Recorder 38 (1): 24. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ East Coast Joys: Tom Purvis and the LNER

- ↑ Frazier, J.L. (1925). Type Lore. Chicago. p. 20. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- 1 2 Shinn, Nick. "Uniformity" (PDF). Nick Shinn. Graphic Exchange. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul. "Helvetica and Univers addendum". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Schwartz, Christian. "Neue Haas Grotesk". Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ↑ "Neue Haas Grotesk". The Font Bureau, Inc. p. Introduction.

- ↑ "Neue Haas Grotesk". History. The Font Bureau, Inc.

- 1 2 Specimens of type, borders, ornaments, brass rules and cuts, etc. : catalogue of printing machinery and materials, wood goods, etc. American Type Founders Company. 1897. p. 340. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ Typolexicon.de: Grotesk

- ↑ Lawson 1990, p. 295.

- ↑ OED Definition of Gothic

- ↑ The Sans Serif Typefaces

- ↑ Haralambous 2007, p. 411.

- ↑ Open Document Format for Office Applications (OpenDocument) Version 1.2, Part 1: Introduction and OpenDocument Schema, Committee Draft 04, 15 December 2009, retrieved 2010-05-01

- ↑ OpenDocument v1.1 specification (PDF), retrieved 2010-05-01

- ↑ Microsoft Corporation (June 1992), Microsoft Product Support Services Application Note (Text File) - GC0165: RICH-TEXT FORMAT (RTF) SPECIFICATION (TXT), retrieved 2010-03-13

- ↑ Childers; Griscti; Leben (January 2013). "25 Systems for Classifying Typography: A Study in Naming Frequency" (PDF). The Parsons Journal for Information Mapping (The Parsons Institute for Information Mapping) V (1). Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ Baines, Phil; Haslam, Andrew (2005), Type and Typography, Laurence King Publishing, p. 51, ISBN 9781856694377, retrieved May 23, 2014

In British Standards Classification of Typefaces (BS 2961:1967), the following are defined:

Grotesque: Lineale typefaces with 19th-century origins. There is some contrast in thickness of strokes. They have squareness of curve, and curling close-set jaws. The R usually has a curled leg and the G is spurred. The ends of the curved strokes are usually oblique. Examples include Stephenson Blake Grotesque No. 6, Condensed Sans No. 7, Monotype Headline Bold.

Neo-grotesque: Lineale typefaces derived from the grotesque. They have less stroke contrast and are more regular in design. The jaws are more open than in the true grotesque and the g is often open-tailed. The ends of the curved strokes are usually horizontal. Examples include Edel/Wotan, Univers, Helvetica.

Humanist: Lineale typefaces based on the proportions of inscriptional Roman capitals and Humanist or Garalde lower-case, rather than on early grotesques. They have some stroke contrast, with two-storey a and g. Examples include Optima, Gill Sans, Pascal.

Geometric: Lineale typefaces constructed on simple geometric shapes, circle or rectangle. Usually monoline, and often with single-storey a. Examples include Futura, Erbar, Eurostile. - ↑ Coles, Stephen. "Helvetica alternatives". FontFeed. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Hoefler & Frere-Jones. "Knockout". Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Hoefler & Frere-Jones. "Knockout sizes". Hoefler & Frere-Jones.

- ↑ "Knockout styles". Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Lippa, Domenic. "10 favourite fonts". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Meggs 2011, pp. 376-377.

- ↑ Ulrich, Ferdinand. "Types of their time – A short history of the geometric sans". FontShop. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Meggs 2011, pp. 339-340.

- 1 2 Tracy 1986, pp. 86-90.

- ↑ Blackwell, written by Lewis (2004). 20th-century type (Rev. ed.). London: Laurence King. p. 201. ISBN 9781856693516.

- ↑ Lawson 1990, pp. 326-330.

- ↑ Millington, Roy (2002). Stephenson Blake: The Last of the Old English Typefounders. Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 1-58456-086-X.

- ↑ Tankard, Jeremy. "Bliss". Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ "Speak Up Archive: Saab or Dodgeball?". Underconsideration.com. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ « Previous Next » Commentary. "Questioning Gill Sans - Typography Commentary". Typographica. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen. "Identifont blog Feb 15". Identifont. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- Bringhurst, Robert (2004), The Elements of Typographic Style (3rd ed.), Hartley & Marks Publishers, ISBN 9780881792065

- Haralambous, Yannis (28 November 2007), Fonts & Encodings, O'Reilly Media, ISBN 9780596102425

- Lawson, Alexander (1990), Anatomy of a Typeface, David R. Godine, Publisher, ISBN 9780879233334

- Lyons, Martyn (2011), Books: A Living History (2nd ed.), Getty Publications, ISBN 9781606060834

- Meggs, Philip B.; Purvis, Alston (2011), Meggs' History of Graphic Design (5th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 9781118017760

- Tracy, Walter (1986), Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design, David R. Godine, Publisher, ISBN 9780879236366

- Kupferschmid, Indra, Some Type Genres Explained

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||