Chandragupta Maurya

| Chandragupta Maurya | |

|---|---|

|

Statue of Chandragupta Maurya, Laxminarayan Temple | |

| 1st Mauryan emperor | |

| Reign | c. 324 – c. 297 BCE[1] |

| Predecessor | Dhana Nanda of the Nanda Empire |

| Successor | Bindusara |

| Born |

340 BCE Pataliputra (now in Bihar) |

| Died |

297 BCE (aged 41–42)[1] Shravanabelagola, Karnataka[2] |

| Spouse | Durdhara and a daughter of Seleucus I Nicator |

| Issue | Bindusara |

| Greek | Sandrocottus |

| Dynasty | Maurya |

| Maurya Kings (324 BCE – 180 BCE) | |

| Chandragupta | (324-297 BCE) |

| Bindusara | (297-273 BCE) |

| Ashoka | (268-232 BCE) |

| Dasharatha | (232-224 BCE) |

| Samprati | (224-215 BCE) |

| Shalishuka | (215-202 BCE) |

| Devavarman | (202-195 BCE) |

| Shatadhanvan | (195-187 BCE) |

| Brihadratha | (187-180 BCE) |

| Pushyamitra (Shunga Empire) |

(180-149 BCE) |

Chandragupta Maurya (IAST: Candragupta Maurya, c. 340 – c. 297 BCE) was the founder of the Maurya Empire and the first emperor to unify most of Greater India into one state. He ruled from 324 BCE until his voluntary retirement and abdication in favour of his son, Bindusara, in 297 BCE.[1][3][4]

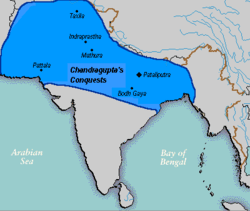

Chandragupta Maurya was a pivotal figure in the history of India. Prior to his consolidation of power, most of the Indian subcontinent was divided into mahajanapadas, while the Nanda Empire dominated the Indo-Gangetic Plain.[5] Chandragupta succeeded in conquering and subjugating almost all of the Indian subcontinent by the end of his reign,[nb 1] except Tamil Nadu (Chera, Early Cholas and Early Pandyan Kingdom) and modern-day Odisha (Kalinga). His empire extended from Bengal in the east to Afghanistan and Balochistan in the west, to the Himalayas and Kashmir in the north, and to the Deccan Plateau in the south. It was the largest empire yet seen in Indian history.[6][7]

In Greek and Latin accounts, Chandragupta is known as Sandrokottos and Androcottus.[8] He became well known in the Hellenistic world for conquering Alexander the Great's easternmost satrapies, and for defeating the most powerful of Alexander's successors, Seleucus I Nicator, in battle. Chandragupta subsequently married Seleucus's daughter to formalize an alliance and established a policy of friendship with the Hellenistic kingdoms, which stimulated India's trade and contact with the western world. The Greek diplomat Megasthenes, who visited the Maurya capital Pataliputra, is an important source of Maurya history.

After unifying much of India, Chandragupta and his chief advisor Chanakya passed a series of major economic and political reforms. He established a strong central administration patterned after Chanakya’s text on politics, the Arthashastra. Chandragupta's India was characterised by an efficient and highly organised bureaucratic structure with a large civil service. Due to its unified structure, the empire developed a strong economy, with internal and external trade thriving and agriculture flourishing. In both art and architecture, the Maurya Empire made important contributions, deriving some of its inspiration from the culture of the Achaemenid Empire and the Hellenistic world.[9] Chandragupta's reign was a time of great social and religious reform in India. Buddhism and Jainism became increasingly prominent. According to Jain accounts, Chandragupta abdicated his throne in favour of his son Bindusara, embraced Jainism, and followed Bhadrabahu and other monks to South India. He is said to have ended his life at Shravanabelagola (in present-day Karnataka) through Sallekhana.

Early life

Very little is known about Chandragupta's youth and ancestry. What is known is gathered from later classical Sanskrit literature, as well as classical Greek and Latin sources which refer to Chandragupta by the names "Sandracottos" or "Andracottus".[8]

Many Indian literary traditions connect him with the Nanda Dynasty in modern-day Bihar in eastern India. More than half a millennium later, the Sanskrit drama Mudrarakshasa calls him a "Nandanvaya" i.e. the descendant of Nanda (Act IV). Chandragupta was born into a family left destitute by the death of his father, chief of the migrant Mauryas, in a border fray.[10] Mudrarakshasa uses terms like kula-hina and Vrishala for Chandragupta's lineage. According to Bharatendu Harishchandra's translation of the play, his father was the Nanda king Mahananda and his mother was a barber's wife named Mora, hence the surname Maurya.[11] This reinforces Justin's contention that Chandragupta had a humble origin.[12][13] On the other hand, the same play describes the Nandas as of Prathita-kula, i.e. illustrious, lineage. The Buddhist text the Mahavamsa calls Chandragupta a member of a division of the(Kshatriya) clan called the Moriya. The Mahaparinibbana Sutta states that the Moriyas (Mauryas) belonged to the Kshatriya community of Pippalivana i.e. possibly Pipli on the outskirts of Kurukshetra. These traditions indicate that Chandragupta came from a Kshatriya lineage. The Mahavamshatika connects him with the Shakya clan of the Buddha, a clan which also belongs to the race of Ādityas.[14]

In Buddhist tradition, Chandragupta Maurya was a member of the Kshatriyas and that his son, Bindusara, and grandson, the famous Buddhist Ashoka, were of Kshatriya lineage, perhaps of the Sakya line. (The Sakya line of Kshatriyas is considered to be the lineage of Gautama Buddha, and Ashoka Maurya billed himself as "Buddhi Sakya" in one of his inscriptions.) [15]

Plutarch reports that he met with Alexander the Great, probably around Takshasila in the northwest, and that he viewed the ruling Nanda Empire in a negative light:

Androcottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth.

According to this text, the encounter would have happened around 326 BCE, suggesting a birth date for Chandragupta around 340 BCE. Plutarch and other Greco-Roman historians appreciated the gravity of Chandragupta Maurya's conquests. Justin describes the humble origins of Chandragupta, and explains how he later led a popular uprising against the Nanda king.[16]

Foundation of the Maurya Empire

Chandragupta Maurya, with the help of Chanakya, defeated the Magadha king and the army of the Chandravanshi clan. Following his victory, the defeated generals of Alexander settled in Gandhara (the Kamboja kingdom), today's Afghanistan. At the time of Alexander's invasion, Chanakya was a teacher in Takshasila. The king of Takshasila and Gandhara, Ambhi (also known as Taxiles), made a peace treaty with Alexander. Chanakya, however, planned to defeat the foreign invasion and sought help from other kings to unite and fight Alexander. Parvateshwara (Porus), a king of Punjab, was the only local king who was able to challenge Alexander at the Battle of the Hydaspes River, but he was defeated.

Chanakya then went further east to Magadha, to seek the help of Dhana Nanda, who ruled the vast Nanda Empire which extended from Bihar and Bengal in the east to Punjab and Sindh in the west,[16] but Dhana Nanda refused to help him. After this incident, Chanakya began to persuade his disciple Chandragupta of the need to build an empire that could protect Indian territories from foreign invasion.

Nanda army

According to Plutarch, at the time of the Battle of the Hydaspes, the Nanda Empire's army numbered 200,000 infantry, 80,000 cavalry, 8,000 chariots, and 6,000 war elephants, which discouraged Alexander's men and prevented their further progress into India:

As for the Macedonians, however, their struggle with Porus blunted their courage and stayed their further advance into India. For having had all they could do to repulse an enemy who mustered only twenty thousand infantry and two thousand horse, they violently opposed Alexander when he insisted on crossing the river Ganges also, the width of which, as they learned, was thirty-two furlongs, its depth a hundred fathoms, while its banks on the further side were covered with multitudes of men-at‑arms and horsemen and elephants. For they were told that the kings of the Ganderites and Praesii were awaiting them with eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand fighting elephants. And there was no boasting in these reports. For Androcottus, who reigned there not long afterwards, made a present to Seleucus of five hundred elephants, and with an army of six hundred thousand men overran and subdued all India.

In order to defeat the powerful Nanda army, Chandragupta needed to raise a formidable army of his own.[17]

Conquest of the Nanda Empire

Chanakya had trained and guided Chandragupta and together they planned the destruction of Dhana Nanda. The Mudrarakshasa of Visakhadutta as well as the Jain work Parisishtaparvan talk of Chandragupta's alliance with the Himalayan king Parvatka, sometimes identified with Porus.[18]

It is noted in the Chandraguptakatha that Chandragupta and Chanakya were initially rebuffed by the Nanda forces. Regardless, in the ensuing war, Chandragupta faced off against Bhadrasala, the commander of Dhana Nanda's armies. He was eventually able to defeat Bhadrasala and Dhana Nanda in a series of battles, culminating in the siege of the capital city Pataliputra[16] and the conquest of the Nanda Empire around 322 BCE,[16] thus founding the powerful Maurya Empire in Northern India by the time he was about 20 years old.

Conquest of Macedonian territories in India

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Chandragupta turned his attention to Northwestern South Asia (modern Pakistan), where he defeated the satrapies (described as "prefects" in classical Western sources) left in place by Alexander (according to Justin), and may have assassinated two of his governors, Nicanor and Philip.[4][16] The satrapies he fought may have included Eudemus, ruler in western Punjab until his departure in 317 BCE; and Peithon, ruler of the Greek colonies along the Indus River until his departure for Babylon in 316 BCE. The Roman historian Justin described how Sandrocottus (the Greek version of Chandragupta's name) conquered the northwest:

Some time after, as he was going to war with the generals of Alexander, a wild elephant of great bulk presented itself before him of its own accord, and, as if tamed down to gentleness, took him on its back, and became his guide in the war, and conspicuous in fields of battle. Sandrocottus, having thus acquired a throne, was in possession of India, when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness; who, after making a league with him, and settling his affairs in the east, proceeded to join in the war against Antigonus. As soon as the forces, therefore, of all the confederates were united, a battle was fought, in which Antigonus was slain, and his son Demetrius put to flight.

Expansion

Conquest of Seleucus' eastern territories

Seleucus I Nicator, a Macedonian satrap of Alexander, reconquered most of Alexander's former empire and put under his own authority the eastern territories as far as Bactria and the Indus (Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55), until in 305 BCE he entered into conflict with Chandragupta:

Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus. He crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship. Some of these exploits were performed before the death of Antigonus and some afterward.

The exact details of engagement are not known. As noted by scholars such as R. C. Majumdar and D. D. Kosambi, Seleucus appears to have fared poorly, having ceded large territories west of the Indus to Chandragupta. Due to his defeat, Seleucus surrendered Arachosia (modern Kandahar), Gedrosia (modern Balochistan), Paropamisadae (or Gandhara).[19][20]

Mainstream scholarship asserts that Chandragupta received vast territory west of the Indus, including the Hindu Kush, modern day Afghanistan, and the Balochistan province of Pakistan.[21][22] Archaeologically, concrete indications of Maurya rule, such as the inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka, are known as far as Kandhahar in southern Afghanistan.

After having made a treaty with him [Sandrakotos] and put in order the Orient situation, Seleucos went to war against Antigonus.

It is generally thought that Chandragupta married Seleucus's daughter to formalize an alliance. In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500 war-elephants,[19][23][24][25][26][27] a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 302 BCE. In addition to this treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Maurya court at Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar state). Later Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka the Great, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Maurya court.[28]

Classical sources have also recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus:

And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters [as to make people more amorous]. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love.

Southern conquest

After annexing Seleucus' eastern Persian provinces, Chandragupta had a vast empire extending across the northern parts of Indian Sub-continent, from the Bay of Bengal to the Arabian Sea. Chandragupta then began expanding his empire further south beyond the barrier of the Vindhya Range and into the Deccan Plateau except the Tamil regions (Pandya, Chera, Chola and Satyaputra) and Kalinga (modern day Odisha).[16] The famous Tamil poet Mamulanar of the Sangam literature also described how the Deccan Plateau was invaded by the Maurya army.[29] By the time his conquests were complete, Chandragupta had succeeded in unifying most of Southern Asia. Megasthenes later recorded the size of Chandragupta's army as 400,000 soldiers, according to Strabo:

Megasthenes was in the camp of Sandrocottus, which consisted of 400,000 men.

On the other hand, Pliny, who also drew from Megasthenes' work, gives even larger numbers of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants:

But the Prasii surpass in power and glory every other people, not only in this quarter, but one may say in all India, their capital Palibothra, a very large and wealthy city, after which some call the people itself the Palibothri,--nay even the whole tract along the Ganges. Their king has in his pay a standing army of 600,000-foot-soldiers, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 elephants: whence may be formed some conjecture as to the vastness of his resources.

Jainism and death

-

Bhadrabahu Goopha (a cave on Chandragiri Hill, Shravanabelagola) is said to be the death place of Chandragupta

-

Chandragupta Basadi, Chandragiri Hill, Shravanabelagola

-

Purportedly the mark of Chandragupta's footprints in Karnataka, India, not far from the cave where he observed fasts in accordance with Jain beliefs

-

Relief at Shravanabelagola depicting the arrival of Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta Maurya

According to numerous Jain accounts such as those in Brihakathā kośa (931 CE), Bhadrabāhu charita (1450 CE), Munivaṃsa bhyudaya (1680 CE) etc., Chandragupta became an ardent follower of Jainism in his later years, renounced his throne, and followed Jain monks led by Bhadrabahu to south India. He is said to have lived as an ascetic at Shravanabelagola for several years before starving himself to death, as per Jain practice of sallekhana. These accounts are also supported by present-day names of local features near Shravanabelagola, and several inscriptions dating from 7th-15th century that refer to Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta in conjunction. Historians such as Vincent Smith and R. K. Mookerji consider the accounts unproven but plausible as they explain the sudden disappearance of Chandragupta from the throne at a young age.[30][31][32][33]

Successors

After Chandragupta's renunciation, his son Bindusara succeeded as the Maurya Emperor. He maintained friendly relations with Greek governors in Asia and Egypt. Bindusara's son Ashoka became one of the most influential rulers in India's history due to his extension of the Empire to the entire Indian subcontinent as well as his role in the worldwide propagation of Buddhism.

In popular culture

- Chanakya's role in formation of the Maurya Empire is the essence of a historical/spiritual novel The Courtesan and the Sadhu by Dr. Mysore N. Prakash.[34]

- The story of Chanakya and Chandragupta was made into a film in Telugu Language in 1977 titled Chanakya Chandragupta. Akkineni Nageswara Rao played the role of Chanakya, while N. T. Rama Rao portrayed as Chandragupta.[35]

- The television series Chanakya is an account of the life and times of Chanakya, based on the play "Mudra Rakshasa" (The Signet Ring of "Rakshasa").

- In 2011, Chandragupt Maurya ,a television series was aired on Imagine TV.[36][37][38]

- The Indian Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp honoring Chandragupta Maurya in 2001.[39]

- In the American comic strip Pearls Before Swine a girl named "Carla" mentions the story of him becoming an ascetic, although she says monk, and starving to death.[40]

See also

- Chandragiri Hill

- Bhagrathi community (Western UP)

- Alexander The Great

- Ancient Macedonian army

- Arthashastra

- Chanakya

- Greco-Bactrian

- Indo-Greek Kingdom

- List of Indian monarchs

- Mauryan art

- Sulehria

- Rags to riches

Notes

- ↑ The conquest of the Deccan is a matter of conjecture. Either Chandragupta or his son and successor Bindusara established Maurya rule over southern parts of India, except the Tamil regions. Old Jaina tets report that Chandragupta was a follower of that religion and ended his life in Karnataka by fasting unto death. If this report is true, Chandragupta may have started the conquest of the Deccan.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 Singh 2008, p. 331.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 40.

- 1 2 Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 59-65.

- 1 2 Boesche 2003, p. 9-37.

- ↑ Shastri 1967, p. 26.

- ↑ Vaughn, Bruce (2004). "Indian Geopolitics, the United States and Evolving Correlates of Power in Asia". Geopolitics 9 (2): 440–459 [442]. doi:10.1080/14650040490442944.

- ↑ Goetz, H. (1955). "Early Indian Sculptures from Nepal". Artibus Asiae 18 (1): 61–74. doi:10.2307/3248838. JSTOR 3248838.

- 1 2 Thapar 2004, p. 177.

- ↑ Sen, S. N. (1999). Ancient Indian History And Civilization. New Age International. p. 165. ISBN 978-8122411980.

- ↑ "Chandragupta". Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ Harishchandra, Bhartendu. Mudrarakshas Hindi Bharatendu Harischandra 1925. p. 10.

- ↑ "He (Seleucus) next made an expedition into India, which, after the death of Alexander, had shaken, as it were, the yoke of servitude from its neck, and put his governors to death. The author of this liberation was Sandrocottus, who afterwards, however, turned their semblance of liberty into slavery; for, making himself king, he oppressed the people whom he had delivered from a foreign power with a cruel tyranny. This man was of mean origin, but was stimulated to aspire to regal power by supernatural encouragement for, having offended Alexander by his boldness of speech, and orders being given to kill him, he saved himself by swiftness of foot; and while he was lying asleep, after his fatigue, a lion of great size having come up to him, licked off with his tongue the sweat that was running from him, and after gently waking him, left him. Being first prompted by this prodigy to conceive hopes of royal dignity, he drew together a band of robbers, and solicited the Indians to support his new sovereignty. Some time after, as he was going to war with the generals of Alexander, a wild elephant of great bulk presented itself before him of its own accord, and, as if tamed down to gentleness, took him on its back, and became his guide in the war, and conspicuous in fields of battle. Sandrocottus, having thus acquired a throne, was in possession of India" (Justin "Epitome of the Philippic History" XV-4)

- ↑ There is a controversy about Justin's account. Justin actually refers to a name Nandrum, which many scholars believe is reference to Nanda (Dhana Nanda of Magadha), while others say that it refers to Alexandrum, i.e., Alexander. It makes some difference which version one believes

- ↑ "optional indian history ancient india". google.co.in.

- ↑ "Chandragupta Maurya". india-religion.net.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mookerji 1988, p. 6.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 28-33.

- ↑ John Marshall Taxila, p. 18, and al.

- 1 2 Ramesh Chandra Majumdar; Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. 1977. ISBN 81-208-0436-8.

- ↑ Aria (modern Herat) "has been wrongly included in the list of ceded satrapies by some scholars [...] on the basis of wrong assessments of the passage of Strabo [...] and a statement by Pliny." (Raychaudhuri, H. C.; Mukherjee, B. N. 1996. Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. Oxford University Press, p. 594). Seleucus "must [...] have held Aria", and furthermore, his "son Antiochos was active there fifteen years later." (Grainger, John D. 1990, 2014. Seleukos Nikator: Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom. Routledge. p. 109).

- ↑ Vincent A. Smith (1998). Ashoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1303-1.

- ↑ Walter Eugene, Clark (1919). "The Importance of Hellenism from the Point of View of Indic-Philology". Classical Philology 14 (4): 297–313. doi:10.1086/360246.

- ↑ Ancient India, (Kachroo ,p.196)

- ↑ The Imperial Gazetteer of India, (Hunter,p.167)

- ↑ The evolution of man and society, (Darlington ,p.223)

- ↑ Tarn, W. W. (1940). "Two Notes on Seleucid History: 1. Seleucus' 500 Elephants, 2. Tarmita". The Journal of Hellenic Studies 60: 84–94. doi:10.2307/626263. JSTOR 626263.

- ↑ Partha Sarathi Bose (2003). Alexander the Great's Art of Strategy. Gotham Books. ISBN 1-59240-053-1.

- ↑ "Pliny the Elder, The Natural History (eds. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S., H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A.)".

- ↑ A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th century by Upinder Singh p.331

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, pp. 39-41.

- ↑ Thapar 2004, p. 178.

- ↑ Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Samuel 2010, pp. 60.

- ↑ The Courtesan and the Sadhu, A Novel about Maya, Dharma, and God, October 2008, Dharma Vision LLC., ISBN 978-0-9818237-0-6, Library of Congress Control Number: 2008934274

- ↑ "Chanakya Chandragupta (1977)". IMDb.

- ↑ "Chandragupta Maurya comes to small screen". Zee News.

- ↑ "Chandragupta Maurya on Sony TV?". The Times of India.

- ↑ TV, Imagine. "Channel". TV Channel.

- ↑ COMMEMORATIVE POSTAGE STAMP ON CHANDRAGUPTA MAURYA, Press Information Bureau, Govt. of India

- ↑ Stephan Pastis. "Pearls Before Swine Comic Strip, September 23, 2013 on GoComics.com". GoComics.

Bibliography

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A history of ancient and early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century, New Delhi: Pearson Longman, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Boesche, Roger (January 2003). "Kautilya's Arthaśāstra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India" (PDF). The Journal of Military History 67 (1): 9. doi:10.1353/jmh.2003.0006. ISSN 0899-3718.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India (Fourth ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15481-2.

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966]. Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (4th ed.). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-0433-3.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Shastri, Nilakantha (1967). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0465-1.

- Thapar, Romila (2004) [first published by Penguin in 2002], Early India: From the Origins to A.D. 1300, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8

Further reading

| Library resources about Chandragupta Maurya |

- Rice, Benjamin Lewis (1889), Inscriptions at Sravana Belgola : a chief seat of the Jains, Bangalore: Mysore Govt. Central Press

- Kosambi, D.D. An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1985

- Kalyani Chandrashekhar Gatole,Bhargava, P.L. Chandragupta Maurya, New Delhi:D.K. Printworld, 160 pp., 2002.

- Habib, Irfan. and Jha, Vivekanand. Mauryan India: A People's History of India,New Delhi:Tulika Books, 2004; 189pp

- Swearer, Donald. Buddhism and Society in Southeast Asia (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania: Anima Books, 1981) ISBN 0-89012-023-4

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass, [1967] c1952) ISBN 0-89684-167-7

- Bongard-Levin, G. M. Mauryan India (Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division May 1986) ISBN 0-86590-826-5

- Chand Chauhan, Gian. Origin and Growth of Feudalism in Early India: From the Mauryas to AD 650 (Munshiram Manoharlal January 2004) ISBN 81-215-1028-7

- Keay, John. India: A History (Grove Press; 1 Grove Pr edition May 10, 2001) ISBN 0-8021-3797-0

- Indica by Megasthenes

- Thomas, Edward (1877), "Jainism or The early faith of Asoka", Nature (London: London, Trübner & co.) 16 (407): 329, Bibcode:1877Natur..16..329, doi:10.1038/016329a0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chandragupta Maurya. |

- Shepherd boy Chandragupta Maurya at the Wayback Machine (archived July 5, 2010)

- 1911encyclopedia.org article on Chandragupta Maurya

- Chandragupta Maurya mentioned in Bhagavata Purana

| Preceded by Nanda Empire |

Mauryan Emperor 322–298 BC |

Succeeded by Bindusara |

|