San Esteban chuckwalla

| San Esteban chuckwalla[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Iguania |

| Family: | Iguanidae |

| Genus: | Sauromalus |

| Species: | S. varius |

| Binomial name | |

| Sauromalus varius Dickerson, 1919 | |

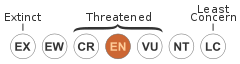

The San Esteban chuckwalla (Sauromalus varius), also known as the Piebald chuckwalla, Pinto chuckwalla or just chuck for short, is a species of chuckwalla belonging to the Iguanidae family endemic to San Esteban Island in the Gulf of California. It is the largest of the five species of chuckwallas and the most endangered.

Taxonomy and etymology

The generic name, Sauromalus, is a combination of two Ancient Greek words:σαῦρος (sauros) meaning "lizard". and ομαλυς (omalus) meaning "flat".[2] Its specific name varius is Latin for "speckled," in reference to the chuckwalla's mottled coloration.[3][4] It was first described by American herpetologist Mary C. Dickerson in 1919.[5]

The common name chuckwalla derives from the Shoshone word "tcaxxwal" or Cahuilla "caxwal", transcribed by Spaniards as "chacahuala". The Seri people named originally the island for this species: Coftécöl lifa or the Peninsula of the Giant Chuckwalla.[6]

Distribution and habitat

The San Esteban chuckwalla is endemic to San Esteban Island in the Gulf of California.[3] While it is abundant on this small island, it occurs naturally nowhere else and is protected under the Endangered Species Act. At one time the Seri translocated populations of this lizard to other islands in the Sea of Cortés as a food item, however, none of these populations have survived beyond the original population found on San Esteban.[6]

Behavior and reproduction

Harmless to humans, these large lizards are known to run from potential threats.[7] When disturbed, the chuckwalla will wedge itself into a tight rock crevice, gulp air, and inflate its body in order to entrench itself.[7]

Males are seasonally and conditionally territorial; an abundance of resources tends to create a hierarchy based on size, with one large male dominating the area's smaller males.[7] Chuckwallas use a combination of colour and physical displays, namely "push ups", head-hobbing, and gaping of the mouth to communicate and defend their territory (see animal communication).[7]

Chuckwallas are diurnal animals and as they are ectothermic, spend much of their mornings and winter days basking in the sun.[7] These lizards are well adapted to desert conditions; they are active at temperatures of up to 102°F (39°C).[7]

Mating occurs from April to July, with 5–16 eggs laid between June and August. The eggs hatch in late September.[7] San Esteban chuckwallas may live for 25 years or more.

Diet

Chuckwallas prefer dwelling in lava flows and rocky areas with nooks and crannies available for a retreat when threatened. These areas are typically vegetated by creosote bush and cholla cacti which form the staple of their diet as the chuckwalla is primarily herbivorous. Chuckwallas also feed on leaves, fruit and flowers of annuals, perennial plants, and even weeds; insects represent a supplementary prey if eaten at all.

Description

.jpg)

The San Esteban chuckwalla is the largest species of chuckwalla reaching 61 centimetres (24 in) in body length, 76 centimetres (30 in) overall length and weighing up to 1.4 kilograms (3.1 lb).[3] It is considered a textbook example of island gigantism as it is 3 to 4 times the size of its mainland counterparts.[3] Their skin is gray with tan to yellow patches over their entire bodies, and their faces are gray to black. Females are duller in appearance with less patches. Their colorations provide almost perfect camouflage against some of their predators.

Human contact

The Comca’ac considered this species of chuckwalla an important food item due to its large size.[8] So much so, that a few lizards were cross-bred with Angel Island chuckwallas and translocated to most of the islands in Bahia de los Angeles: Isla San Lorenzo Norte, Isla San Lorenzo Sur, and Tiburón Island by the Seri people for use as a food source in times of need.[3] This was before the founding of America and most of these populations appear to have died out but the process was repeated by herpeticulturalists in the early 2000s as a way of legally producing a San Esteban-like chuck that the average reptile enthusiast could work with. These are referred to in herpetoculture as the Calico chuck. Luckily the crosses are fertile and seem to have the best traits of both chucks - the brighter coloration of the San Esteban chuckwalla with the calmer temperament of the Angel Island chuckwalla.

The tribe of Seri who once inhabited San Esteban Island referred to themselves as Coftécöl Comcáac, "People of the Giant Chuckwalla" and named the island for this species.[6]

The San Esteban chuckwalla is an endangered species due to hunting from the Seri and the introduction of feral animals such as rats and mice which prey upon the chuckwalla's eggs and feral dogs and cats which prey upon the lizards.[6] Due to these factors and overcollection from the pet trade, the species was declared an Appendix I animal under CITES.

There is an in situ chuckwalla captive breeding program in Punta Chueca, a Seri village on the Mexican mainland.[6] A successful ex situ program has also been in place at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum since 1977. The species is present in private collections and is often crossbred with the smaller Angel Island chuckwalla.

References

- ↑ "Sauromalus varius". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ↑ Schwenkmeyer, Dick. "Sauromalus ater Common Chuckwalla". Field Guide. San Diego Natural History Museum. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Case, T. J. (1982). Ecology and evolution of insular gigantic chuckwallas, Sauromalus hispidus and Sauromalus varius. Iguanas of the World (Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications). pp. 184–212. ISBN 0-8155-0917-0.

- ↑ Hollingsworth, Bradford D. (2004). The Evolution of Iguanas an Overview and a Checklist of Species. Iguanas: Biology and Conservation (University of California Press). pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1.

- ↑ Dickerson, M. C. (1919). Diagnoses of twenty-three new species and a new genus of lizards from Lower California. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 41 (10): 461–477

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nabhan, Gary (2003). Singing the Turtles to Sea: The Comcáac (Seri) Art and Science of Reptiles. University of California Press. p. 350. ISBN 0-520-21731-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stebbins, Robert C.,(2003) A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians, 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 0-395-98272-3

- ↑ Richard Felger and Mary B. Moser (1985) People of the desert and sea: ethnobotany of the Seri Indians Tucson: University of Arizona Press.