San Antonio Palopó

| San Antonio Palopó | |

|---|---|

| Municipality and village | |

|

| |

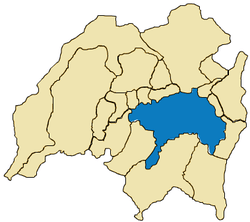

San Antonio Palopó location of San Antonio Palopó in Guatemala | |

San Antonio Palopó location of San Antonio Palopó in Sololá Department | |

| Coordinates: GT 14°42′N 91°7′W / 14.700°N 91.117°W | |

| Country |

|

| Department |

|

| Named for | St. Anthony of Padua |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal |

| • Mayor (2016-2020) | Francisco Calabajay Díaz[1] |

| Lowest elevation | 1,562 m (5,125 ft) |

| Time zone | Central Time (UTC-6) |

| Country calling code | 502 |

| Climate | Cwb |

San Antonio Palopó is a municipality in the Sololá department of Guatemala. The village is on the eastern shore of Lake Atitlán. The lowest elevation is 1,562 metres (5,125 ft) at the shoreline. The people of the region are Cakchiquel Maya with a distinctive style of clothing. The patron saint of the village is St. Anthony of Padua. The annual festival takes place on 13 June.[2]

History

Spanish colony: Franciscan doctrine

After the Spanish conquest of Guatemala the town was in charge of the franciscans, who had convents and doctrines in the area covered by the modern departaments of Sacatepéquez, Chimaltenango, Sololá, Quetzaltenango, Totonicapán, Suchitepéquez and Escuintla. The "Provincia del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús" (English:"Province of the most Holy Name of Jesus"), as the Franciscan area was called back then, reached up to 24 convents by 1700.[3]

The franciscans tried to have daily religious teaching for 6 year old girls and older starting at 2:00 pm and for boys of the same age starting at sunset; the class lasted for 2 hours and consisted on memorizing the church teaching and prayers and to make some exercises with the catechism and it was run by a priest or by elder natives, called "fiscales".[4] Adults attended Mass every Sunday and holiday and after mass, there were religious teachings in their own language.[4]

Lent was a time of the year when the friars prepared the natives thoroughly, using their own language to accomplish their goals; every Friday of Lent there was a procession following the Rosary steps all the way to the Calvary temple.[5]

In 1754, as part of the borbon reforms, the Franciscans where forced to gave their doctrines to the secular clergy;[6] thus, when archbishop Pedro Cortés y Larraz visited town in 1770, he described it as part of the "San Francisco Panajachel parish".[7]

1892 archeologist Alfred P. Maudslay visit

In 1892, British archeologist Alfred Percival Maudslay and his wife Anne Maudslay visited Guatemala and traveled throughout it on mules, arriving to San Antonio Palopó on their way through Sololá; Anne Maudslay's impressions were recorded in her book A glimpse at Guatemala where tells how, in order to reach Panajachel coming from Chimaltenango, they had to go down a very steep path, forcing them to send their belongings ahead with several natives who were used to the path, while they took a longer way with their mules.[11] Once they reached Lake Atitlan level, the climb a small hill to get to the native town of San Antonio.[11]

The Maudslays climbed the steep street towards town hall, where they intended to spend the night but found out that the corridors were already crowded with native travelers and their cargo; when they inquired about the building rooms, they found out that there were only two: one that was used as prison and was crowded with prisoners, and one that was used for municipal business.[12] They had to look for another shelter, and finally found it in the local school, where they were allowed to spend the night in the girls classroom, which had no windows and no lights. While searching for a place to stay the nights, they noticed that the local church had no roofing, as a results of the periodic earthquakes that affect the area.[12]

The year the Maudslays visited town, there were only five ladinos living in it: the school teacher and his wife, the municipality secretary and two ladies that had a small grocery shop; everybody else was native Guatemalan, and even the municipality was completely led by native people.[8] Due to the rise of coffee plantations in those years, a road had just been built, to shorten the travel time from the south shores of Guatemala to Quetzaltenango, thus, bringing San Antonio Palopó out of it partial isolation; nevertheless, Anne Maudslay found strange that both women and girls would flee shyly after glancing at them, and were reluctant to have their pictures taken.[8] In spite of that, the Maudslay could observe that the female population was clean and tidy with their clothes, and numerous women were by the lake shore washing their hair.[10]

There was another custom that the Maudslays observed: since it was Sunday, all the municipality authorities were out in a procession, going house by house talking to their constituents about the business for the upcoming days: dressed with their black clothes and their mayoral sticks, theirs was a solemn procession; once all the houses had been notified, one of the men shouted some more instructions that were repeated in farther locations for two or three times and with that, the group dissolved.[9]

Since they were staying at the town school, they could see a class: little boys showed up early, dressed exactly like their parents with the difference that the red handkerchief on their heads looked older and seemed to have been passed from fathers to sons; the kids put literally their faces in their books, too shy to see the visitors until the teacher came and took roll call.[9] After that, the teacher stepped out and the children went back to their book, for the next three hours, as the teacher could not speak their language and the did not know any Spanish.[9] That day there was not class for the girls, who were dismissed because the visitors were staying at their class.[9]

Like other native towns that they had visited, the Maudslay reported that the clothing the people used was all handcrafted and made in their own homes using primitive systems, similar to those pictured in the Codex Mendoza, who Alfred Maudslay had seen back in England.[13]

Administrative division

The municipality has an area of 34 km² and one municipal capital, two villages, five settlements and three neighborhoods.[14]

| Administrative location | List |

|---|---|

| Municipal capital | San Antonio Palopó |

| Villages |

|

| Settlements |

|

| Neighborhoods |

|

Climate

San Antonio Palopó has temperate climate (Köppen: Csb).

| Climate data for San Antonio Palopó | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.2 (75.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23 (73.41) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.1 (61) |

17.38 (63.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.8 (49.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.2 (55.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.8 (55) |

12.5 (54.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.73 (53.11) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1 (0.04) |

7 (0.28) |

6 (0.24) |

30 (1.18) |

102 (4.02) |

298 (11.73) |

168 (6.61) |

168 (6.61) |

304 (11.97) |

156 (6.14) |

44 (1.73) |

7 (0.28) |

1,291 (50.83) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[15] | |||||||||||||

Geographic location

San Antonio is located 27 km south of Sololá, the department capital and 158 km west of Guatemala City. It is surrounded by Sololá Department municipalities, except on the east, where it borders Patzún, a Chimaltenango Department municipality.[16]

|

San Andrés Semetabaj and Santa Catarina Palopó |  | ||

| Lake Atitlán | |

Patzún, Chimaltenango Department municipality[16] | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| San Lucas Tolimán[16] |

See also

- Guatemala portal

- Geography portal

- List of places in Guatemala

References

- ↑ "Alcaldes electos en el departamento de Sololá". Municipalidades de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala. 7 September 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ "San Antonio Palopó" (in Spanish). INGUAT, the Guatemalan Ministry of Tourism.

- ↑ García Añoveros 1989, p. 891

- 1 2 García Añoveros 1989, p. 896

- ↑ García Añoveros 1989, p. 897

- ↑ Juarros 1818, p. 338.

- ↑ Cortés y Larraz 2001, p. 409-412.

- 1 2 3 Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 53

- 1 2 3 4 5 Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 54

- 1 2 Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 55

- 1 2 Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 51

- 1 2 3 Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 52

- ↑ Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, p. 56.

- 1 2 Mazariegos Guzmán 2008, p. 8

- ↑ "Climate: San Antonio Palopó". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 SEGEPLAN. "Municipios del departamento de Sololá". SEGEPLAN (in Spanish). Guatemala. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

Bibliography

- Cortés y Larraz, Pedro (2001) [1770]. García, Jesús María; Blasco, Julio Martín, ed. Descripción Geográfico-Moral de la Diócesis de Goathemala. Corpus Hispanorum de Pace. Segunda Serie (in Spanish). Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. ISBN 9788400080013. ISSN 0589-8056.

- García Añoveros, Jesús (1989). "Las misiones franciscanas de la Mosquitia nicaragüense" (PDF). Actas del III Congreso Internacional sobre los franciscanos en el nuevo mundo (Siglo XVII) (in Spanish) (Madrid, Spain: DEIMOS; Universidad Internacional de Andalucía).

- Juarros, Domingo (1818). Compendio de la historia de la Ciudad de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Ignacio Beteta.

- Maudslay, Alfred Percival; Maudslay, Anne Cary (1899). A glimpse at Guatemala, and some notes on the ancient monuments of Central America (PDF). London, UK: John Murray.

- Mazariegos Guzmán, Erik Ovidio (2008). Municipio de San Antonio Palopó, departamento de Sololá: Organización empresarial (engorde de ganado porcino) y proyecto de producción de arveja china (PDF). Ejercicio profesional supervisado (in Spanish). Guatemala: Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

External links

-

Media related to San Antonio Palopó at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to San Antonio Palopó at Wikimedia Commons

Coordinates: 14°42′N 91°07′W / 14.700°N 91.117°W