Samizdat

| Samizdat | |

| Russian | самиздат |

|---|---|

| Romanization | samizdat |

| Literal meaning | self-publishing |

Samizdat (Russian: самизда́т; IPA: [səmɨzˈdat]) was a key form of dissident activity across the Soviet bloc in which individuals reproduced censored publications by hand and passed the documents from reader to reader. This grassroots practice to evade officially imposed censorship was fraught with danger, as harsh punishments were meted out to people caught possessing or copying censored materials.

Vladimir Bukovsky summarized it as, "I myself create it, edit it, censor it, publish it, distribute it, and get imprisoned for it."[1]

Name origin and variations

Etymologically, the word samizdat derives from sam (Russian: сам, "self, by oneself") and izdat (Russian: издат, an abbreviation of издательство, izdatel'stvo, "publishing house"), and thus means "self-published". The Ukrainian language has a similar term: samvýdav (самвидав), from sam, "self", and vydannya, "publication".[2]

The Russian poet Nikolai Glazkov coined a version of the term as a pun in the 1940s when he typed copies of his poems and included the note Samsebyaizdat (Самсебяиздат, "Myself by Myself Publishers") on the front page.

Tamizdat refers to literature published abroad (там, tam, "there"), often from smuggled manuscripts.

Techniques

Samizdat copies of texts, such as Mikhail Bulgakov's novel The Master and Margarita or Václav Havel's essay The Power of the Powerless were passed around among trusted friends. The techniques used to reproduce these forbidden texts varied. Several copies might be made using carbon paper, either by hand or on a typewriter; at the other end of the scale mainframe printers were used during night shifts to make multiple copies, and books were at times printed on semiprofessional printing presses in much larger quantities. Before glasnost, the practice was dangerous, because copy machines, printing presses, and even typewriters in offices were under control of the organisation's First Department, i.e. the KGB: reference printouts for all of these machines were stored for subsequent identification purposes, if samizdat output was found.

Physical form

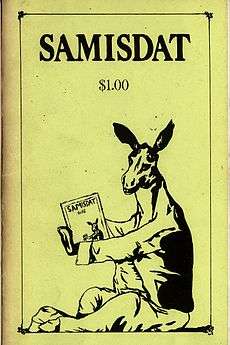

Samizdat distinguishes itself not only by the ideas and debates which it helped spread to a wider audience, but also by its physical form. The hand-typed, often blurry and wrinkled pages with numerous typographical errors and nondescript covers helped to separate and elevate Russian samizdat from Western literature.[3] The physical form of samizdat arose from a simple lack of resources and the necessity to be inconspicuous. In time dissidents in the USSR began to admire these qualities for their own sake, the ragged appearance of samizdat contrasting sharply with the smooth, well-produced appearance of texts passed by the censor's office for publication by the State. The form samizdat took gained precedence over the ideas it expressed, and became a potent symbol of the resourcefulness and rebellious spirit of the inhabitants of the Soviet Union.[4] In effect, the physical form of samizdat itself elevated the reading of samizdat to a prized clandestine act.[5]

Readership

Samizdat originated from the dissident movement of the Russian intelligentsia, and most samizdat directed itself to a readership of Russian elites. While circulation of samizdat was relatively low, at around 200,000 readers on average, many of these readers possessed positions of cultural power and authority.[6] Furthermore, due to the presence of "dual consciousness" in the Soviet Union, the simultaneous censorship of information and necessity of absorbing information to know how to censor it, many government officials became readers of samizdat.[7] Though the general public at times came into contact with samizdat, most of the public lacked access to the few, expensive samizdat texts in circulation, and expressed discontent with the highly censored reading material made available by the state.[8]

The purpose and methods of samizdat may contrast with the purpose of the concept of copyright.[9]

History

Self-published and self-distributed literature has a long history in Russia. Samizdat is unique to the post-Stalin USSR and other countries with similar systems. Under the grip of censorship of the police state, society turned to underground literature for self-analysis and self-expression.[10]

At the outset of the Khrushchev Thaw in the mid-1950s USSR, poetry became very popular and writings of a wide variety of known, prohibited, repressed, as well as young and unknown poets circulated among Soviet intelligentsia.

On June 29, 1958, a monument to Vladimir Mayakovsky was opened in the centre of Moscow. The official ceremony ended with impromptu public poetry readings. The Moscovites liked the atmosphere of relatively free speech so much that the readings became regular and came to be known as "Mayak" (Russian: Маяк, the lighthouse), with students being a majority of participants. However, it did not last long as the authorities began clamping down on the meetings. In the summer of 1961, several meeting regulars (among them Eduard Kuznetsov) were arrested and charged with "anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda" (Article 70 of the RSFSR Penal Code). Editor and publisher of Moscow samizdat magazine "Синтаксис" (Sintaksis) Alexander Ginzburg was arrested in 1960.

Certain works published legally in the State-controlled media, such as the novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (November 1962 issue of the Novy Mir literary magazine) were practically impossible to find in bookshops and libraries. On an order from above they could just as easily be removed from circulation. So this and other works found its way into samizdat. Solzhenitsyn's The First Circle and Cancer Ward followed, after 1968 publication abroad.[11]

Not everything published in samizdat had political overtones. In 1963, Joseph Brodsky was charged with "social parasitism" and convicted for being nothing but a poet. In the mid-1960s, the Youngest Society of Geniuses, an underground literary group known by the acronym SMOG (СМОГ – "Самое Молодое Общество Гениев", Samoye Molodoye Obshchestvo Geniyev; the acronym also forms the Russian verb for I, He, One "Could") issued an almanac titled The Sphinxes ("Сфинксы") and collections of prose and poetry. Some of their writings were close to Russian avantgarde of the 1910s–1920s.

The 1965 show trial of writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky (Sinyavsky–Daniel trial, also charged with violating Article 70) and increased repressions marked the demise of the Thaw and harsher times for samizdat authors. The trial was carefully documented in The White Book by Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg. Both writers were later arrested and sentenced to prison in what was known as The Trial of the Four. Some of the samizdat content became more politicized and played an important role in the dissident movement in the Soviet Union.

Samizdat periodicals

The earliest samizdat periodicals were short-lived and mainly literary in focus: Vladimir Osipov's Boomerang (1960) and the Phoenix (1961), produced by Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg. From 1964 to 1970, communist historian Roy Medvedev regularly published The Political Journal (in Russian Политический дневник or political diary) which contained analytical materials that later appeared in the West.

The longest-running and best-known samizdat periodical was A Chronicle of Current Events (Хроника текущих событий).[12] It was dedicated to defending human rights by providing accurate information about events in the USSR. Over 15 years from April 1968 to December 1982, 65 issues were published, all but two appearing in English translation.[13] The anonymous editors encouraged the readers to utilize the same distribution channels in order to send feedback and local information to be published in the subsequent issues.

The Chronicle was distinguished by its dry concise style and punctilious correction of the smallest error. Its regular rubrics were "Arrests, Searches, Interrogations", "Extra-judicial Persecution", "In Prisons and Camps", "Samizdat update", "News in brief", and "Persecution of Religion". Over time sections were added on the "Persecution of the Crimean Tatars", "Persecution and Harassment in Ukraine", "Lithuanian Events", and so on.

The Chronicle editors maintained that according to the 1936 Soviet Constitution then in force their publication was not illegal. The authorities did not accept the argument. Many people were harassed, arrested, imprisoned, or forced to leave the country for their involvement in the Chronicle's production and distribution. The periodical's typist and first editor Natalya Gorbanevskaya was arrested and put in a psychiatric hospital for taking part in the August 1968 Red Square protest against the invasion of Czechoslovakia. In 1974 two of the periodical's close associates (Pyotr Yakir and Victor Krasin) were persuaded to denounce their fellow editors and the Chronicle on Soviet television. This put an end to the periodical's activities until Sergei Kovalev, Tatyana Khodorovich and Tatyana Velikanova openly announced their readiness to resume publication. After being arrested and imprisoned they themselves were replaced, in turn, by others.

Another notable and long-running (about 20 issues in the period of 1972–1980) publication was the refusenik political and literary magazine "Евреи в СССР" (Yevrei v SSSR, Jews in the USSR), founded and edited by Alexander Voronel and, after his imprisonment, by Mark Azbel and Alexander Luntz.

Not all samizdat trends were liberal or clearly opposed to the Soviet regime and the literary establishment. "The Russian Party... was a very strange element of the political landscape of Leonid Brezhnev's era – feeling themselves practically dissidents, members of the Russian Party with rare exceptions took quite prestigious official positions in the world of writers or journalists," wrote Oleg Kashin in 2009.[14]

Genres of samizdat

Samizdat covered a large range of topics, mainly including literature and works focused on religion, nationality, and politics.[15] The state censored a variety of materials such as detective novels, adventure stories, and science fiction in addition to dissident texts, resulting in the underground publication of samizdat covering a wide range of topics. Though most samizdat authors directed their works towards the intelligentsia, samizdat included lowbrow genres in addition to scholarly works.[16]

Literary

In its early years, samizdat defined itself as a primarily literary phenomenon which included the distribution of poetry, classic unpublished Russian literature, and famous 20th century foreign literature.[17]:148 Literature played a key role in the existence of the samizdat phenomenon. For instance, the USSR's refusal to publish Boris Pasternak's epic novel, Doctor Zhivago, due to its focus on individual characters rather than the welfare of the state, led to the novel's subsequent underground publication. The fact that Doctor Zhivago contained no overt messages of dissidence highlighted the clumsiness of the state's censorship process, which caused a shift of readership away from state-published material.[18] Likewise, the circulation of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's famous work detailing the horrors of the gulag system, The Gulag Archipelago, promoted a samizdat revival during the mid-1970s.[19] However, because samizdat by definition placed itself in opposition to the state, samizdat works became increasingly focused on the state's violation of human rights, before shifting towards politics.[20] An analysis of the largest archive of samizdat, Arkhiv Samizdata, reveals that literary samizdat composed merely 1% of the total body of samizdat.[15]

Political

The majority of samizdat texts were politically focused.[15] Most of the political texts were personal statements, appeals, protests, or information on arrests and trials.[21] Other political samizdat included analyses of various crises within the USSR, and suggested alternatives to the government's handling of events. No unified political thought existed within samizdat; rather, authors debated from a variety of perspectives. Samizdat written from socialist, democratic and Slavophile perspectives dominated the debates.[22]

Socialist authors compared the current state of the government to the Marxist ideals of socialism, and appealed to the state to fulfill its promises. Socialist samizdat writers hoped to give a "human face" to socialism by expressing dissatisfaction with the system of censorship.[23] Many socialists put faith in the potential for reform in the Soviet Union, especially because of the political liberalization which occurred under Dubček in Czechoslovakia. However, the Soviet Union invasion of a liberalizing Czechoslovakia in the events of "Prague Spring" crushed hopes for reform and stymied the power of the socialist viewpoint.[24] Because the state proved itself unwilling to reform, samizdat began to focus on alternative political systems. Within samizdat, several works focused on the possibility of a democratic political system. Democratic samizdat possessed a revolutionary nature because of its claim that a fundamental shift in political structure was necessary to reform the state, unlike socialists who hoped to work within the same basic political framework to achieve change. Despite the revolutionary nature of the democratic samizdat authors, most democrats advocated moderate strategies for change. Most democrats believed in an evolutionary approach to achieving democracy in the USSR, and focused on advancing their cause along open, public routes, rather than underground routes.[25]

In opposition to both democratic and socialist samizdat, Slavophile samizdat grouped democracy and socialism together as Western ideals which were unsuited to the Eastern European mentality. Slavophile samizdat brought a nationalistic Russian perspective to the political debate and espoused the importance of cultural diversity and the uniqueness of Slavic cultures. Samizdat written from the Slavophile perspective attempted to unite the USSR under a vision of a shared glorious history of Russian autocracy and Orthodoxy. Consequently, the fact that the USSR encompassed a diverse range of nationalities and lacked a singular Russian history hindered the Slavophile movement. By espousing frequently racist and anti-Semitic views of Russian superiority through either purity of blood or the strength of the Russian Orthodoxy, the Slavophile movement in samizdat alienated readers and created divisions within the opposition.[26]

Religious

Samizdat about religion composed about 20% of the total materials in the Arkhiv Samizdata. Predominantly Baptist, Orthodox, Pentecostalist, Catholic, and Adventist groups authored samizdat texts. Though a diversity of religious samizdat circulated, including three Buddhist texts, no known Islamic samizdat texts exist. The lack of Islamic samizdat appears incongruous with the large percentage of Muslims who resided in the USSR.[21]

Nationalist

About 17% of the texts in Arkhiv Samizdata center on issues of nationality.[15] Jewish samizdat importantly advocated for the end of repression of Jews in the USSR, and expressed a desire for exodus, the ability to leave Russia for an Israeli homeland. The exodus movement also broached broader topics of human rights and freedoms of Soviet citizens.[27] However, a divide existed within Jewish samizdat between authors who advocated exodus and those who argued that Jews should remain in the USSR to fight for their rights. Crimean Tartars and Volga Germans also wrote samizdat protesting the state's refusal to allow them to return to their homelands following Stalin's death. Ukrainian samizdat opposed the assumed superiority of Russian culture over Ukrainian culture and condemned the forced assimilation of Ukrainians to the Russian language.[28] In addition to samizdat focused on Jewish, Ukrainian, and Crimean Tartar concerns, authors also advocated the causes of a great many other nationalities.

Contraband audio

Ribs, "music on the ribs", "bone records",[29] or roentgenizdat (roentgen- referring to X-ray, and -izdat implying samizdat) were homemade phonograph records, copied from forbidden recordings that were smuggled into the country. Their content was Western rock and roll, jazz, mambo, and other music, and music by banned emigres. They were sold and traded on the black market.

Each disc is a thin, flexible plastic sheet recorded with a spiral groove on one side, playable on a normal phonograph turntable at 78RPM. They were made from an inexpensive, available material: used X-ray film. Each large rectangular sheet was trimmed into a circle and individually recorded using an improvised recording lathe. The discs and their limited sound quality resemble the mass-produced flexi disc, and may have been inspired by it.

Magnitizdat, less common, is the distribution of sound recordings on audio tape, often of underground music groups, bards, or lectures. (magnit- referring to magnetic tape)

Similar phenomena in other countries

In the long history of the Polish underground press, the usual term in the later years of Communism was drugi obieg or "second circulation" (of publications), with the implied first circulation being legal and censored publications. The term bibuła ("blotting paper") is older, having been used even during the partitions of Poland.

Lithuania has a long history of underground press.

After Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was exiled by the Shah of Iran in 1964, his sermons were smuggled into Iran on cassette tapes and widely copied, increasing his popularity and leading, in part, to the Iranian Revolution. After the Iranian Revolution led to the establishment of an Islamic state, the situation reversed. Works like Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses (1988) appeared inside the Religious Republic in illegal Samizdat editions.

A tradition of publishing handwritten material existed in the German military during both the first and second world wars.

China has a history of underground handwritten manuscripts of books officially banned by the authorities, although not all banned books were of a political nature: books such as the erotic novel Jin Ping Mei were also banned to "protect public morals."

After Bell Labs changed its UNIX license to make dissemination of the source code illegal, the Lions Book had to be withdrawn, but illegal copies of it circulated for years. The act of copying the Lions book was often referred to as Samizdat. See Lions' Commentary on UNIX 6th Edition, with Source Code for more information.

Some samizdat periodicals in the Soviet Union

See also

- Censorship in the Soviet Union

- Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Human rights in the Soviet Union

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1970s–87)

- Gosizdat

- Eastern Bloc media and propaganda

References

- ↑ (Russian) "Самиздат: сам сочиняю, сам редактирую, сам цензурирую, сам издаю, сам распространяю, сам и отсиживаю за него." (autobiographical novel И возвращается ветер..., And the Wind returns... NY, Хроника, 1978, p.126) Also online at http://www.vehi.net/samizdat/bukovsky.html

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Ukraine, s.v. Samvydav.

- ↑ Komaromi 2004, p. 608–609.

- ↑ Komaromi 2004, p. 609.

- ↑ Komaromi 2004, p. 605.

- ↑ Stelmakh, "Reading in the Context of Censorship in the Soviet Union," 147.

- ↑ Meerson-Aksenov, "Introductory: The Dissident Movement and Samizdat," 22.

- ↑ Stelmakh, "Reading in the Context of Censorship in the Soviet Union," 149.

- ↑ For example: Feldbrugge, Ferdinand Joseph Maria (1975). Samizdat and Political Dissent in the Soviet Union. Brill. p. 23. ISBN 9789028601758. Retrieved 2015-06-29.

Another legal aspect of samizdat literature is the copyright problem. [...] It grew into an important issue when the Soviet government, in an apparent attempt to impede the publication of samizdat materials abroad, joined the Geneva Convention in 1973. [...] Well-known Soviet authors, such as Solzhenitsyn, whose works regularly appear in samizdat in the Soviet Union have never claimed that their copyright was infringed by the samizdat procedure.

- ↑ (Russian) History of Dissident Movement in the USSR. The birth of Samizdat by Ludmila Alekseyeva. Vilnius, 1992

- ↑ Helen Rappaport (1999), Joseph Stalin: A biographical companion, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576072088.

- ↑ A Chronicle of Current Events, 1968–1982 (in Russian) Archive at memo.ru.

- ↑ A Chronicle of Current Events 1968–1983 (in English). All 1968 and 1969 issues may be found in Peter Reddaway, Uncensored Russia, Jonathan Cape: London, 1972.

- ↑ "A true but Russian dissident", Oleg Kashin, Russian Life, June 2009

- 1 2 3 4 Joo 2004, p. 572.

- ↑ Komaromi 2004, p. 606.

- ↑ Stelmakh, Valeria (Winter 2001). "Reading in the context of censorship in the Soviet Union". Libraries & Culture 36 (1): 143–151. doi:10.1353/lac.2001.0022. JSTOR 25548897.

- ↑ Meerson-Aksenov, Michael. Introductory: The Dissident Movement and Samizdat. The Political, Social and Religious Thought of Russian 'Samizdat'-An Anthology. Edited by Michael Meerson-Aksenov, Boris Shragin. Belmont, MA: Nordland Publishing Company, 1977, 27.

- ↑ Joo 2004, p. 575.

- ↑ Meerson-Aksenov, "Introductory: The Dissident Movement and Samizdat," 30.

- 1 2 Joo 2004, p. 574.

- ↑ Joo 2004, p. 576.

- ↑ Shragin, Boris, Socialism with a Human Face. The Political, Social and Religious Thought of Russian 'Samizdat'-An Anthology, 47.

- ↑ Joo 2004, p. 587.

- ↑ Joo 2004, p. 587–588.

- ↑ Joo 2004, p. 588.

- ↑ Meerson-Aksenov, "The Jewish Question in the USSR – The Movement for Exodus," 385–86.

- ↑ Joo 2004, p. 573–574.

- ↑ "Bones And Grooves: The Weird Secret History Of Soviet X-Ray Music".

Further reading

- Outsiders' works

- Samizdat 1 – La voix de l'opposition communiste en U.R.S.S. [Samizdat 1 – The voice of the communist opposition in the USSR] (in French). Paris: Seuil. 1969. ASIN B00R4QXXSO.

- Aron, Leon (July–August 2009). "Samizdat in the 21st century. Russia's new literature of crisis". Foreign Policy (173): 131–133. JSTOR 20684899.

- Barghoorn, Frederick (Spring–Summer 1983). "Regime-dissenter confrontation in the USSR: samizdat and Western views, 1972–1982". Studies in Comparative Communism 16 (1–2): 99–119. doi:10.1016/0039-3592(83)90046-7.

- Boiter, Albert (July 1972). "Samizdat: primary source material in the study of current Soviet affairs". The Russian Review 31 (3): 282–285. doi:10.2307/128049. JSTOR 128049.

- Brun-Zejmis, Julia (Autumn 1991). "Messianic consciousness as an expression of national inferiority: Chaadaev and some samizdat writings of the 1970s". Slavic Review 50 (3): 646–658. JSTOR 2499860.

- Bungs, Dzintra (September 1988). "Joint political initiatives by Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians as reflected in samizdat materials—1969–1987". Journal of Baltic Studies 19 (3): 267–271. doi:10.1080/01629778800000181.

- Daughtry, Martin (Spring 2009). "“Sonic Samizdat”: situating unofficial recording in the post-Stalinist Soviet Union". Poetics Today 30 (1): 27–65. doi:10.1215/03335372-2008-002.

- Ehrhardt, Nelli (2008). Samizdat in der Sowjetunion der 60–70er Jahre [Samizdat in the Soviet Union the 60–70s] (in German). GRIN Verlag. ISBN 3640175425.

- Emerson, Susan (December 1982). "Writers who protest and protesters who write; a guide to Soviet dissent literature". Collection Building 4 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1108/eb023073.

- Feldbrugge, Ferdinand Joseph Maria (1976). "Samizdat and political dissent in the Soviet Union". Review of Socialist Law 2 (1). doi:10.1163/157303576X00256.

- Feldbrugge, Ferdinand Joseph Maria (1975). Samizdat and political dissent in the Soviet Union. BRILL. ISBN 9028601759.

- Gregor, Gregor (2015). Auf Der Suche Nach Politischer Gemeinschaft: Oppositionelles Denken Zur Nation Im Ostmitteleuropäischen Samizdat 1976–1992 (Ordnungssysteme) [Looking for political community: Oppositional thinking to the nation in the East-Central European samizdat (Inventory Systems)] (in German). de Gruyter Oldenbourg. ISBN 3110419777.

- Gribanov, Alexander; Kowell, Masha (Spring 2009). "Samizdat according to Andropov". Poetics Today 30 (1): 89–106. doi:10.1215/03335372-2008-004.

- Johnston, Gordon (May 1999). "What is the history of samizdat?". Social History 24 (2): 115–133. doi:10.1080/03071029908568058. JSTOR 4286559.

- Joo, Hyung-min. Voices of freedom: samizdat. Europe-Asia Studies. June 2004;56(4):571–594. doi:10.1080/0966813042000220476.

- Kiebuzinskia, Ksenya (2012). "Samizdat and dissident archives: trends in their acquisition, preservation, and access in North American repositories". Slavic and East European Information Resources 13 (1): 3–25. doi:10.1080/15228886.2012.653661.

- Kind-kovacs, Friederike; Labov, Jessie (2012). Samizdat, tamizdat, and beyond: transnational media during and after socialism. Berghahn Books. ISBN 0857455850.

- Komaromi, Ann. The material existence of Soviet samizdat. Slavic Review. Autumn 2004;63(3):597–618. doi:10.2307/1520346.

- Komaromi, Ann (Spring 2012). "Samizdat and Soviet dissident publics". Slavic Review 71 (1): 70–90. doi:10.5612/slavicreview.71.1.0070. JSTOR 10.5612/slavicreview.71.1.0070.

- Komaromi, Ann (2015). Uncensored: samizdat novels and the quest for autonomy in Soviet dissidence. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810131862.

- Küpper, Stephen (September 1998). "Präprintium. A Berlin exhibition of Moscow samizdat books". Other Voices 1 (2).

- Loeber, Dietrich (September 1973). "Samizdat under Soviet law. On the legal status of Russia's unofficial and unpublished writings". Index on Censorship 2 (3): 3–26. doi:10.1080/03064227308532240.

- Oushakine, Serguei (Spring 2001). "The terrifying mimicry of Samizdat". Public Culture 13 (2): 191–214. doi:10.1215/08992363-13-2-191.

- Pospielovsky, Dimitry (March 1978). "From Gosizdat to Samizdat and Tamizdat". Canadian Slavonic Papers 20 (1): 44–62. doi:10.1080/00085006.1978.11091512. JSTOR 40867266.

- Reddaway, Peter (1972). Uncensored Russia – protest and dissent in the Soviet Union. The unofficial Moscow journal, A Chronicle of Current Events. New York: American Heritage Press. ISBN 0070513546.

- Sharlet, Robert (1974). "Samizdat as a source for the study of Soviet law". The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 1 (1): 181–196. doi:10.1163/187633274x00144.

- Ronza, R (1970). Samizdat: dissenso e contestazione nell'Unione Sovietica [Samizdat: dissent and protest in the Soviet Union] (in Italian). Milan: IPL. ISBN 8878362034.

- Saunders, George (1974). Samizdat: voices of the Soviet opposition. Pathfinder Press. ISBN 0873489144.

- Skilling, Gordon (1989). Samizdat and an independent society in Central and Eastern Europe. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0814204872.

- Svirskii, Grigorii (1981). A history of post-war Soviet writing: the literature of moral opposition. Ann Arbor: Ardis Publishing. ISBN 0882334492.

- Telesin, Julius (February 1973). "Inside "Samizdat"". Encounter 40 (2): 25–33.

- Toker, Leona (Winter 2008). "Samizdat and the problem of authorial control: the case of Varlam Shalamov". Poetics Today 29 (4): 735–758. doi:10.1215/03335372-083.

- Treynor, Jack (March–April 1994). "Samizdat: the investment value of plant". Financial Analysts Journal 50 (2): 12–17. JSTOR 4479725.

- Treynor, Jack (July–August 1993). "Samizdat: the value of control". Financial Analysts Journal 49 (4): 6–9. JSTOR 4479661.

- Woll, Josephine; Treml, Vladimir (1983). Soviet dissident literature: a critical guide. G K Hall. ISBN 081618626X.

- Yakushev, Alexei (April 1975). "The Samizdat movement in the USSR: a note on spontaneity and organization". The Russian Review 34 (2): 186–193. doi:10.2307/127716. JSTOR 127716.

- Zaslavskaya, Olga (Winter 2008). "From dispersed to distributed archives: the past and the present of samizdat material". Poetics Today 29 (4): 669–712. doi:10.1215/03335372-081.

- Zisserman-Brodsky, Dina (2003). Constructing ethnopolitics in the Soviet Union: samizdat, deprivation and the rise of ethnic nationalism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403973628.

- Тупикин, Влад (2001). "Самиздат после перестройки" [Samizdat after perestroika]. Index on Censorship (in Russian) (13).

- Insiders' works

- Andropov, Yuri (May 1995). "The birth of samizdat". Index on Censorship 24 (3): 62–63. doi:10.1080/03064229508535948.

- Glazov, Yuri (Winter 1973). "Samizdat". Survey: 75–91.

- Gorbanevskaïa, Natalia (2009). "Samizdat et Internet" [Samizdat and Internet]. Revue Russe (in French) 33 (1): 137–143.

- Gorbanevskaya, Natalya (January 1977). "Writing for 'samizdat'". Index on Censorship 6 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1080/03064227708532600.

- Mal'tsev, Yuri (1976). L'altra letteratura (1957–1976): la letteratura del samizdat da Pasternak a Solženicyn [The other literature (1957–1976): the samizdat literature from Pasternak to Solzhenitsyn] (in Italian). Milan: La Casa di Matriona.

- Medvedev, Roy (Spring 1971). "Samizdat: Jews in the USSR". Survey: 185–200.

- Medvedev, Roy; Strada, Vittorio (1977). Dissenso e socialismo: una voce marxista del Samizdat sovietico [Dissent and socialism: a Marxist voice of Soviet samizdat] (in Italian). Turin: Giulio Einaudi.

- Medvedev, Roy (1977). The Samizdat register 1. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 039305652X.

- Medvedev, Roy (1981). Samizdat Register 2: Voices of the socialist opposition in the Soviet Union. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 039333578X.

- Sinyavsky, Andrei (August 1980). "Samizdat and the rebirth of literature". Index on Censorship 9 (4): 8–13. doi:10.1080/03064228008533086.

External links

- December 1970 report by KGB regarding "alarming political tendencies"in Samizdat and Preventive measures (from the Soviet Archives collected by Vladimir Bukovsky)

- Alexander Bolonkin – Memoirs of Soviet Political Prisoner detailing some technology used

- Anthology of samizdat

- Igrunov, Vyacheslav, ed. (2005). Антология самиздата. Неподцензурная литература в СССР. 1950–1980-е.: В 3-х томах: т. 1 книга 1: до 1966 [Anthology of samizdat. Uncensored literature in the USSR. The 1950s–1980s. In 3 volumes. Volume 1, book 1: till 1966] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Международный институт гуманитарно-политических исследований. ISBN 5-89793-031-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2013.

- Igrunov, Vyacheslav, ed. (2005). Антология самиздата. Неподцензурная литература в СССР. 1950–1980-е.: В 3-х томах: т. 1 книга 2: до 1966 [Anthology of samizdat. Uncensored literature in the USSR. The 1950s–1980s. In 3 volumes. Volume 1, book 2: till 1966] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Международный институт гуманитарно-политических исследований. ISBN 5-89793-032-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2013.

- Igrunov, Vyacheslav, ed. (2005). Антология самиздата. Неподцензурная литература в СССР. 1950–1980-е.: В 3-х томах: т. 2: 1966–1973 [Anthology of samizdat. Uncensored literature in the USSR. The 1950s–1980s. In 3 volumes. Volume 2. 1966–1973] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Международный институт гуманитарно-политических исследований. ISBN 5-89793-033-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2013.

- Igrunov, Vyacheslav, ed. (2005). Антология самиздата. Неподцензурная литература в СССР. 1950–1980-е.: В 3-х томах: т. 3: после 1973 [Anthology of samizdat. Uncensored literature in the USSR. The 1950s–1980s. In 3 volumes. Volume 3. After 1973] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Международный институт гуманитарно-политических исследований. ISBN 5-89793-034-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2013.

- Natella Boltyanskaya. "Четвёртая серия. Самиздат и Интернет" [The fourth part. Samizdat and Internet]. Voice of America (in Russian). Parallels, Events, People.

- Samizdat archive Вѣхи (Vekhi Library, in Russian)

- Anthology of Czech samizdat periodicals

- Archive of Robert-Havemann-Society e.V., Berlin

- Arbeitsgruppe Menschenrechte/ Arbeitskreis Gerechtigkeit (Hrsg.): Die Mücke. Dokumentation der Ereignisse in Leipzig, DDR-Samisdat, Leipzig, März 1989.

- IFM-Archiv Sachsen e.V.: Internet-Collection of DDR-Samizdat

- DDR-Samizdat in Archiv Bürgerbewegung Leipzig

- Umweltbibliothek Großhennersdorf e.V.

- DDR-Samisdat in the IISG Amsterdam

- "Samizdat", poem by Jared Carter

- "Chronicle of current events" by Memorial Society

|