Salian Franks

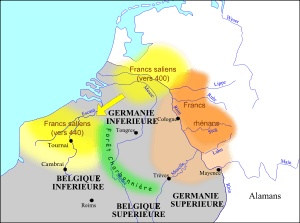

The Salian Franks, also called the Salians (Latin: Salii, Greek: Salioi), were the western subgroup of the early Franks who first appear in the historical records in the third century. At that time they lived between the Rhine and the IJssel in the modern day Dutch region of the Veluwe, Gelderland. As the Salians initially lived north of the Rhine delta, they were also north of the limes of Roman Gaul, which ran along the Rhine. They were characterised as both warlike Germanic people and pirates, and as Laeti (allies of the Romans). Shortly thereafter, some were settled permanently on Roman land. After moving into Batavia, a border island in the Rhine, in 358, they came to some form of agreement with the Romans, which allowed them to settle south of the Rhine in Toxandria (roughly the area of the current Dutch province of Noord-Brabant, and adjacent parts of the two bordering Belgian provinces of Antwerpen and Belgian Limburg, the so-called "Kempen" (French Campine)).

Over time, the Salians fully adopted the Frankish identity and ceased to appear by their original name from the 7th century onward, when they evolved into the Franks par excellence.[1] The Lex Ripuaria originated about 630 around Cologne and has been described as a later development of the Frankish laws known from Lex Salica. The Merovingian kings responsible for the conquest of Gaul are thought to have had Salian ancestry.

Etymology

From the early 6th century on, the name Salian Franks (Salii in Latin)[2] is used to contrast with the Ripuarian Franks. Salii may have derived from the name of the IJssel river, formerly called Hisloa or Hisla, and in ancient times, Sala, which may be the Salians' original residence.[3] Today this area is called Salland. Alternatively, the name may derive from a proposed Germanic word *saljon meaning friend or comrade, indicating that the term initially implied an alliance.[4]

Culture

The Salian Frankish language is ancestral to the modern family of Low Franconian dialects (including Dutch).

The Salian tribes constituted a loose confederacy that banded together to negotiate with Roman authority. Each tribe consisted of extended family groups centered on a particularly renowned or noble family. The importance of the family bond was made clear by the Salic Law, which ordained that an individual had no right to protection if not part of a family.

While the Goths or the Vandals had been at least partly converted to Christianity since the mid-4th century, polytheistic beliefs are thought to have flourished among the Salian Franks until the conversion of Clovis to Christianity shortly before or after 500, after which paganism diminished gradually.[6]

History

The Salian Franks' original proximity to the sea is attested in the first historical records. In about 286 AD, Carausius was put in charge of defending the coasts of the Straits of Dover against Saxon and Frankish pirates.[7] This changed when the Saxons drove them south into Roman territory. Their history is attested by Ammianus Marcellinus and Zosimus, who described their migrations toward the southern Netherlands and Belgium. They first crossed the Rhine during the Roman upheavals and subsequent Germanic breakthrough in 260 AD.

After peace had returned, in 297 AD, the Roman Emperor Constantius Chlorus allowed the Salians to settle among the Batavians, where they soon came to dominate the Batavian island in the Rhine delta. The backgrounds of the seafaring Franks whose story was written down during the reign of emperor Probus (276-282) are not clear. It is not known whether these people were unwillingly obliged to serve the Roman army as had the Batavians before them, or if they were assigned another territory close to the Black Sea. The story tells of a large group who decided to hijack some Roman ships and return with them from Eastern Europe – reaching their homes in the Rhine estuaries without large losses through Greece, Sicily and Gibraltar, although not without causing mayhem.[8] Franks ceased to be associated with seafaring when other Germanic tribes, probably Saxons, drove them to the south. The Salians received protection from the Romans and in return were recruited by Constantius Gallus – together with the other inhabitants of the Batavian isle. This did not prevent the onslaught of the Germanic tribes to the north, especially by the Frankish Chamavi. The subsequent "insolent" settlement of the Salians within Roman territory in Toxandria (between the Meuse and the Scheldt rivers in the Netherlands and Belgium) was rejected by the future Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate, who attacked them. The Salians surrendered to him in 358 AD and accepted Roman terms.[9] According to Zosimus, when the Salians in Batavia came under attack from Saxons, who were this time raiding Romans (and the Salians) from the sea, Julian took the opportunity to peacefully allow the Salii to settle in Toxandria, where they had previously been expelled:

"[Julian] commanded his army to attack them briskly; but not to kill any of the Salii, or prevent them from entering the Roman territories, because they came not as enemies, but were forced there [...] As soon as the Salii heard of the kindness of Caesar, some of them went with their king into the Roman territory, and others fled to the extremity of their country, but all humbly committed their lives and fortunes to Caesar's gracious protection." The Salians were then brought into Roman units defending the empire from other Frankish raiders.[10]

One particular Salian family comes to light in Frankish history in the early fifth century, in time becoming the Merovingians – Salian kings named after Childeric's mythical father Merovech, whose birth was associated with supernatural elements.

From the 420s onwards, headed by a certain Chlodio, they expanded their territory to the Somme into northern France. They formed a kingdom in that area with the Belgian city of Tournai becoming the center of their domain. This kingdom was extended further by Childeric and especially Clovis, who gained control over Roman Gaul, i.e. France, whose current name was derived from the Franks.

In 451, Flavius Aëtius, de facto ruler of the Western Roman Empire, called upon his Germanic allies on Roman soil to help fight off an invasion by Attila's Huns. The Salian Franks answered the call and fought in the battle of the Catalaunian Fields in a temporary alliance with Romans and Visigoths, which de facto ended the Hunnic threat to Western Europe.

Clovis, king of the Salian Franks, became the absolute ruler of a Germanic kingdom of mixed Galloroman-Germanic population in 486. He consolidated his rule with victories over the Gallo-Romans and all the other Frankish tribes and established his capital in Paris. After he had beaten the Visigoths and the Alemanni, his sons drove the Visigoths to Spain and subdued the Burgundians, Alemanni and Thuringians. After 250 years of this dynasty, however, marked by internecine struggles, a gradual decline occurred. The position in society of the Merovingians was taken over by Carolingians, who came from a northern area around the river Maas in what is now Belgium and southern Netherlands.

In Gaul, a fusion of Roman and Germanic societies was occurring. During the period of Merovingian rule, the Franks began to adopt Christianity following the baptism of Clovis I in 496, an event that inaugurated the alliance between the Frankish kingdom and the Roman Catholic Church. Unlike their Goth and Lombard counterparts, who adopted Arianism, the Salians adopted Catholic Christianity early on; they had an intimate relationship with their ecclesiastical hierarchy, subjects, and conquered territories.

The division of the Frankish kingdom among Clovis’s four sons (511) was a precedent that would influence Frankish history for more than four centuries. By then, the Salic Law had established the exclusive right to succession of male descendants. However, this principle turned out to be an exercise in interpretation, rather than the simple implementation of a new model of succession. No trace of an established practice of territorial division can in fact be discovered among Germanic peoples other than the Franks.

By the 9th century, if not earlier, the division between Salian and Ripuarian Franks had in practice become virtually non-existent, but continued for some time to have implications for the legal system under which a person could go on trial. The adjective Salian, as applied to the Frankish people, is the origin of the name of the Salic Law.

Footnotes

- ↑ Dr.D.P.Blok, De Franken in Nederland, Holland: Bussum, 1979. ISBN 90-228-3739-4, p.17

- ↑ The ethnonym is unrelated to the name for the dancing priests of Mars, who were also called Salii.

- ↑ Perry, p. *Perry, Walter Copland (1857). The Franks, from their first appearance in history to the death of King Pepin. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts.

- ↑ Lanting; van der Plicht (2010), "De 14C-chronologie van de Nederlandse Pre- en Protohistorie VI: Romeinse tijd en Merovingische periode, deel A: historische bronnen en chronologische schema’s", Palaeohistoria, 51/52: 69

- ↑ G. Salaün, A. McGregor & P. Périn, "Empreintes inédites de l'anneau sigillaire de Childéric Ier : état des connaissances", Antiquités Nationales, 39 (2008), pp. 217-224 (esp. 218).

- ↑ K. Fischer Drew, The laws of the Salian Franks. Translated and with an Introduction by Katherine Fischer Drew (1991), 6

- ↑ Eutropius, Abridgement of Roman History Book IX:21

- ↑ Zosimus 1814; Musset 1975:68.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, Book XVII-8

- ↑ Zosimus Nova Historia Book III

References

- Primary

- Ammianus Marcellinus, History of the Later Roman Empire.

- Gregory of Tours, Decem Libri Historiarum (Ten Books of Histories, better known as the Historia Francorum).

- Zosimus (1814): New History, London, Green and Chaplin. Book 1.

- Secondary

- Anderson, Thomas. 1995. "Roman Military Colonies in Gaul, Salian Ethnogenesis and the Forgotten Meaning of Pactus Legis Salicae 59.5". Early Medieval Europe 4 (2): 129–44.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1910). Franks, In The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, V. 11, pp. 35–36.

- Musset, Lucien : The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Europe, Ad 400-600,1975, ISBN 1-56619-326-5, p. 68.

- Perry, Walter Copland (1857). The Franks, from Their First Appearance in History to the Death of King Pepin. Longman, Brown, Green: 1857.

- Wood, Ian, The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450-751 AD. 1994.