Salerno

| Salerno | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comune | |||

| Comune di Salerno | |||

|

Panorama of Salerno | |||

| |||

Salerno within the Province of Salerno and Campania | |||

Salerno Location of Salerno in Italy | |||

| Coordinates: 40°41′0″N 14°46′0″E / 40.68333°N 14.76667°ECoordinates: 40°41′0″N 14°46′0″E / 40.68333°N 14.76667°E | |||

| Country | Italy | ||

| Region | Campania | ||

| Province | Salerno (SA) | ||

| Founded | 197 BC | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Vincenzo Napoli (acting) (PSI) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 58.96 km2 (22.76 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 4 m (13 ft) | ||

| Population (30 November 2014)[1] | |||

| • Total | 133,199 | ||

| • Density | 2,300/km2 (5,900/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Salernitani | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 84121 to 84135 | ||

| Dialing code | 089 | ||

| Patron saint | Saint Matthew | ||

| Website | Official website | ||

Salerno [saˈlɛrno] ![]() listen is a city and comune in Campania (south-western Italy) and is the capital of the province of the same name. It is located on the Gulf of Salerno on the Tyrrhenian Sea.

listen is a city and comune in Campania (south-western Italy) and is the capital of the province of the same name. It is located on the Gulf of Salerno on the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Salerno was an independent Lombard principality in the early Middle Ages. During this time, it became the site of the first medical school in the world. In the 16th century, under the Sanseverino family, among the most powerful feudal lords in southern Italy, the city became a great centre of learning, culture and the arts, and the family hired several of the greatest intellectuals of the time.[2] Later, in 1694, the city was struck by several catastrophic earthquakes and plagues.[2] After a period of Spanish rule which would last until the 18th century, Salerno became part of the Parthenopean Republic.[2]

In recent history the city hosted the King of Italy, who moved from Rome in 1943 after Italy negotiated a peace with the Allies in World War II. A brief so-called "government of the South" was then established in the town, which became the "capital" of Italy for some months. Some of the Allied landings during Operation Avalanche (the invasion of Italy) occurred near Salerno.

Today Salerno is an important cultural centre in Campania and Italy and has had a long and eventful history. The city has a rich and varied culture, and the city is divided into three distinct zones: the medieval sector, the 19th century sector and the more densely populated post-war area, with its several apartment blocks.[2]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

The area of what is now Salerno has been continuously settled since pre-historical times, although the first certain signs of human presence date to the period between the 9th and 6th centuries BC. We know the Oscan-Etruscan city of Irna (founded in the 6th century BC), situated across the Irno river, in what is today the quarter of Fratte. This settlement represented an important base for Etruscan trade with the Greek colonies of Posidonia and Elea. It was occupied by the Samnites around the 5th century BC as consequence of the Battle of Cumae (474 BC) as part of the Syracusan sphere of influence.

With the Roman advance in Campania, Irna began to lose its importance, being supplanted by the new Roman colony (197 BC) of Salernum, developing around an initial castrum. The new city, which gradually lost its military function in favour of its role as a trade center, was connected to Rome by the Via Popilia, which ran towards Lucania and Reggio Calabria.

Archaeological remains, although fragmentary, suggest the idea of a flourishing and lively city. Under the Emperor Diocletian, in the late 3rd century AD, Salernum became the administrative centre of the "Lucania and Bruttii" province.

In the following century, during the Gothic Wars, the Goths were defeated by the Byzantines, and the Salerno briefly returned to the control of Constantinople (from 553 to 568), before the Lombards invaded almost the whole peninsula. Like many coastal cities of southern Italy (Gaeta, Sorrento, Amalfi), Salerno initially remained untouched by the newcomers, falling only in 646. It subsequently became part of the Duchy of Benevento.

Middle Ages to early modern

Under the Lombard dukes Salerno enjoyed the most splendid period of its history.

In 774 Arechis II of Benevento transferred the seat of the Duchy of Benevento to Salerno, in order to elude Charlemagne's offensive and to secure for himself the control of a strategic area, the centre of coastal and internal communications in Campania.

With Arechis II, Salerno became a centre of studies with its famous Medical School. The Lombard prince ordered the city to be fortified; the Castle on the Bonadies mountain had already been built with walls and towers. In 839 Salerno declared independence from Benevento, becoming the capital of a flourishing principality stretching out to Capua, northern Calabria and Apulia up to Taranto.

Around the year 1000 prince Guaimar IV annexed Amalfi, Sorrento, Gaeta and the whole duchy of Apulia and Calabria, starting to conceive a future unification of the whole southern Italy under Salerno's arms. The coins minted in the city circulated in all the Mediterranean, with the Opulenta Salernum wording to certify its richness.

However, the stability of the Principate was continually shaken by the Saracen attacks and, most of all, by internal struggles. In 1056, one of the numerous plots led to the fall of Guaimar. His weaker son Gisulf II succeeded him, but the decline of the principality had begun. In 1077 Salerno reached its zenith but soon lost all its territory to the Normans.

On December 13, 1076, the Norman conqueror Robert Guiscard, who had married Guaimar IV's daughter Sikelgaita, besieged Salerno and defeated his brother-in-law Gisulf. In this period the royal palace of Castel Terracena and the cathedral were built, and science was boosted as the Schola Medica Salernitana, considered the most ancient medical institution of European West, reached its maximum splendour. At this time in the late 11th century, the city was home to 50,000 people.[3]

Salerno played a conspicuous part in the fall of the Norman kingdom. After the Emperor Henry VI's invasion on behalf of his wife, Constance, the heiress to the kingdom, in 1191, Salerno surrendered and promised loyalty on the mere news of an incoming army. This so disgusted the archbishop, Nicholas of Ajello, that he abandoned the city and fled to Naples, which held out in a siege. In 1194, the situation reversed itself: Naples capitulated, along with most other cities of the Mezzogiorno, and only Salerno resisted. It was sacked and pillaged, much reducing its importance and prosperity. Henry had his reasons, though. He had entrusted Constance to the citizens and they had betrayed him and handed her over to king Tancred of Sicily. Her combined treachery and stubbornness cost Salerno much after the Hohenstaufen conquest. Henry's son, Frederick II, moreover, issued a series of edicts that reduced Salerno's role in favour of Naples (in particular, the foundation of the University of Naples in that city).

From the 14th century onwards, most of the Salerno province became the territory of the Princes of Sanseverino, powerful feudal lords who acted as real owners of the region. They accumulated an enormous political and administrative power and attracted artists and men of letters in their own princely palace. In the 15th century the city was the scene of battles between the Angevin and the Catalan-Aragonese royal houses with whom the local lords took sides alternatingly.

In the first decades of the 16th century, the last descendent of the Sanseverino princes, Ferdinando Sanseverino, was in conflict with the viceroy of the king of Spain, mainly because of his opposition to the Inquisition, causing the ruin of the whole family and the beginning of a long period of decadence for the city.

A slow renewal of the city occurred in the 18th century with the end of the Spanish dominion and the construction of many refined houses and churches characterising the main streets of the historical centre. In 1799 Salerno was incorporated into the Parthenopean Republic. During the Napoleonic era, first Joseph Bonaparte and then Joachim Murat ascended the Neapolitan throne. The latter decreed the closing of the Schola Medica Salernitana, that had been declining for decades to the level of a theoretical school. In the same period even the religious orders were suppressed and numerous ecclesiastical properties were confiscated.

The city expanded beyond the ancient walls and sea connections were potentiated as they represented an important road network that crossed the town connecting the eastern plain with the area leading to Vietri and Naples.

Late modern and contemporary

Salerno was an active center of Carbonari activities supporting the unification of Italy in the 19th century.[4] The majority of the population of Salerno supported ideas of the Risorgimento, and in 1861 many of them joined Garibaldi in his struggle for unification.[5]

After the unification of Italy, a slow urban development continued, many suburban areas were enlarged and large public and private buildings were created. The city went on developing until the Second World War. Its population rose from 20,000 people around 1861s unification to 80,000 in the early 20th century.

During 19th century, foreign industries started settling in Salerno: in 1830 a first textile mill was established by the Swiss entrepreneur Züblin Vonwiller, followed by Schlaepfer-Wenner's textile mills and dye factories; the Wenner family settled permanently in Salerno. In 1877 the city was the site of as many as 21 textile mills employing around ten thousand workers; in comparison with the four thousand employed in Turin's textile industry, Salerno was sometimes referred to as the "Manchester of the two Sicilies".

In September 1943, during World War II, Salerno was the scene of Operation Avalanche, the invasion of Italy launched by the Allies of World War II, and suffered a great deal of damage. From February 12 to July 17, 1944, it hosted the Government of Marshal Pietro Badoglio. In those months Salerno was the temporary capital of the Kingdom of Italy, and the King Victor Emmanuel III lived in a mansion in its outskirts.

After the war the population of the city doubled in a few years, going from 80,000 in 1946 to nearly 160,000 in 1976.

Geography

The city is situated at the north-western end of the plain of the Sele river, at the exact beginning of the Amalfi coast. The small river Irno crosses through the central section of Salerno. The highest point is Monte Stella with its 953 metres (3,127 ft).[6]

Climate

Salerno has a Mediterranean climate, with a hot and relatively dry summer (30 °C (86 °F) in August) and a rainy fall and winter (8 °C (46 °F) in January). Usually there is nearly 1,000 mm (39 in) of rain every year. The strong wind that comes from the mountains toward the Gulf of Salerno makes the city very windy (mainly in winter). However, this gives Salerno the advantage of being one of the sunniest towns in Italy.

Demographics

In 2007, there were 140,580 people residing in Salerno, located in the province of Salerno, Campania, of whom 46.7% were male and 53.3% were female. Minors (children ages 18 and younger) totalled 19.61 percent of the population compared to pensioners who number 21.86 percent. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06 percent (minors) and 19.94 percent (pensioners). The average age of Salerno residents is 42 compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Salerno grew by 2.02 percent, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.85 percent.[7] The current birth rate of Salerno is 7.77 births per 1,000 inhabitants compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.

As of 31 December 2010, there were 4,355 foreigners in Salerno. The largest immigrant group came from other European countries (mainly Ukraine and Romania).[8] The population is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic.

Economy

The economy of Salerno is mainly based on services and tourism, as most of the city's manufacturing base did not survive the economic crisis of the 1970s. The remaining ones are connected to pottery and food production and treatment.

The Port of Salerno is one of the most active of the Tyrrhenian Sea. It handles about 10 million tons of cargo per year, 60% of which is made up by containers.[9]

Transport

Salerno is connected to the Autostrada A3 and Autostrada A30 motorways.

Salerno station is the main railway station of the city. It is connected to the high-speed railway network via the Milan-Salerno corridor.

A metropolitan railway service connects the station with Stadio Arechi.[10]

A new Maritime Terminal Station will be completed in April 2016 and opened for the 2016/2017 cruise season.[11]

Salerno airport is located in the neighboring towns of Pontecagnano Faiano and Bellizzi.

Education

Salerno hosted the oldest medical school in the world, the Schola Medica Salernitana, the most important source of medical knowledge in Europe in the early Middle Ages. It was closed in 1811 by Joachim Murat.

In 1944 king Vittorio Emanuele III established Istituto Universitario di Magistero "Giovanni Cuomo". In 1968 the university became state-controlled.[12] Today University of Salerno is located in the neighboring town of Fisciano and has about 34,000 students[13] and ten faculties: Arts and Philosophy, Economics, Education, Engineering, Foreign language and literature, Law, Mathematics, Physics and Natural Sciences, Medicine, Pharmacy and Political Science.[14]

Sports

The city's main football team is U.S. Salernitana 1919, that plays in Serie B (the second highest football division in Italy).[15] Its home stadium is Stadio Arechi, opened in 1990 and with a capacity of 37,245.

The most successful team in the city is the women's handball team PDO Handball Team Salerno, with its four national titles, four national cups and two national supercups.

Attractions

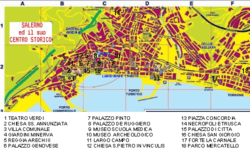

Salerno is located at the geographical center of a triangle nicknamed Tourist Triangle of the 3 P (namely a triangle with the corners in Pompei, Paestum and Positano). This peculiarity gives Salerno special tourist characteristics that are increased by the many local points of tourist interest like the Lungomare Trieste (Trieste Seafront Promenade), the Castello di Arechi (Arechis' Castle), the Duomo (cathedral) and the Museo Didattico della Scuola Medica Salernitana (Educational Museum of the Salernitan Medical School).[16]

Secular sights

- Lungomare Trieste (Trieste Seafront Promenade). This Promenade was created from the sea during the 1950s and it is one of the best in Italy, at the level (and imitation) of those in the French Riviera. It has an extension of nearly five miles (8.0 km) with many rare palms.

- Castello di Arechi ("Arechis' Castle") is a massive castle commanding the city from a 300 m (984.25 ft) hill. It was enlarged by Arechis II over a pre-existing Roman-Byzantine construction. Today it houses rooms for exhibitions and congresses. The Castle offers a complete and spectacular view of the city and the Gulf of Salerno.

- Centro storico di Salerno. The "Historical Downtown of Salerno" is believed to be one of the best maintained in the Italian peninsula. Its "Via dei mercanti" (Merchant street) is even today one of the main shopping streets in the city. The Duomo is its centre.

- Giardino della Minerva. "Minerva's Garden" is situated in the fringes of the castle hill that dominates the old Salerno. In it can be found the medieval "Hortus sanitatis" (Health garden) of the Schola Medica Salernitana, that was the first European "orto botanico" (botanical garden).

- Parco del Mercatello. The "Park of Mercatello (little market)" is situated in the eastern section of the city. It was made in 1998 and with its about twenty acres is one of the biggest in Italy.

- Forte La Carnale. The "La Carnale Castle" got his name from a medieval battle against the Arabs and is part of a sport complex (with pool, tennis courts and hockey). Actually it is used as a cultural center for expositions and meetings.

- Villa Comunale di Salerno (Municipal Park of Salerno). The garden of the old city hall is actually a huge recreation area in front the Salerno Theater (the "Teatro Verdi"), with a fountain (called "Don Tullio") done in 1790.

- Colle Bellara (Bellara Hill), a hill from which it is possible to see the Amalfi Coast up to the Cilento.

- Teatro Verdi. The Salerno Theater ("Teatro Verdi") was done in 1872 and is decorated with paintings of Gaetano D'Agostino. The theater was heavily damaged during the 1980 earthquake and rebuilt in 1994, during the celebrations for the fifty years of "Salerno Capital of Italy".

- Palazzo di Città di Salerno (Town Hall of Salerno). It was constructed in 1936 in typical Fascist style. Its main saloon, the "Marmol Saloon" was the meeting room for the first Government of the Kingdom of Italy after the fall of Fascism in 1943.

- Palazzo Genovese. In baroque style of the 17th century, was rebuilt by the architect Ferdinando Sanfelice.

- Palazzo Pinto. It is situated in the middle of the "Via dei Mercanti" (merchant street) and has the "Pinacoteca Provinciale" (Provincial Pinacotheca).

- Palazzo De Ruggiero. Noble building done in the 16th century, situated near the Cathedral.

- Castel Terracena (Terracena Castle), built by Robert Guiscard in 1076–1086 as a royal mansion, next to the Eastern walls. Only scarce remains (mainly tower-houses in tuff) can be seen today, as it was destroyed by an earthquake in 1275.

- Palazzo Fruscione. Medieval palace erected in the 12th century. It includes walls of the Arechis II Royal Mansion.

- Palazzo Copeta. It is situated in the Lombard section of the city. It hosted the last lessons of the Schola Medica Salernitana during Napoleon times.

- Palazzo d'Avossa. Noble palace rebuilt in the 17th century by the architect Ferdinando Sanfelice. It has frescoes inspired by Torquato Tasso's Gerusalemme liberata

- Palazzo Ruggi d'Aragona. Palace built in the 15th century near the "Via dei Mercanti" (merchant street).

- Palazzo Morese. Built in the 14th century and later renovated in Baroque style, facing the Cathedral.

Churches

- The Cathedral is the main tourist attraction of the city. In its crypt is the tomb of one of the twelve apostles of Christ, Saint Matthew the Evangelist.

- Chiesa della SS. Annunziata (14th century) located near the northern entrance of medieval Salerno (called "Portacatena"). It has a beautiful bell-tower done by the architect Ferdinando Sanfelice.

- Chiesa di San Gregorio. The church was built in the 10th century near the "Via dei Mercanti" (merchant street): a document states its existence in 1058. Actually is the home of the "Museo didattico della Scuola Medica Salernitana" (Museum of the Salerno Medical School).

- Chiesa di San Giorgio. The church of St. George is the most beautiful Baroque church of Salerno. It has paintings of Andrea Sabatini and high-quality frescoes by Francesco and Angelo Solimena (late 17th century). It is related to one of the most ancient monasteries of the city, dating back to the early 9th century, which remains of apse frescoes in have been recently brought to light.

- Chiesa di San Pietro in Vinculis. It is located on the "Piazza Portanova" (Portanova Square) and has Renaissance paintings.

- Chiesa di San Benedetto. The St. Benedict church was originally part of a monastery from 7th–9th centuries, connected to a massive aqueduct whose remains are still visible today. After the Arabs destruction in 884, it was rebuilt by Abbot Angelarius with a nave and two aisles. Remains of an entrance quadriporticus can still be seen.

- Chiesa di Sant'Agostino. The church is renowned for the "Madonna di Costantinopoli" (Our Lady of Costantinople) inside.

- Chiesa del SS. Crocifisso. The church located in the "Via dei Mercanti" (merchant street) has a Cripta of the 10th century.

- Chiesa di San Pietro a Corte. A Lombard church from the 10th century, it was part of Arechis II's royal mansion with the name "Cappella Palatina".

- Chiesa dell'Annunziatella. The church is located near the old Roman Forum and has a beautiful fountain of the 16th century near the entrance.

Monuments

- Faro della Giustizia (Justice Lighthouse). Monument of the Judiciary Citadel of Salerno, near the "Colle Bellara".

- Monumento al Marinaio (Monument to the Sailor), situated in Concordia square, in front of the "Masuccio Salernitano" tourist port.

Museums and galleries

- Museo Archeologico Provinciale (Provincial Archaeological Museum). The Museum is located inside the old "San Benedetto Monastery" and is internationally renowned for its "Testa di Apollo" (head of Apollo).

- Museo Didattico della Scuola Medica Salernitana (Educational Museum of the Salernitan Medical School). Located inside the Lombard church of San Gregorio. The Museum has noteworthy documents from the Schola Medica Salernitana.

- Museo Diocesano di Salerno (Salerno Museum of the Diocese). It is located near the Salerno Cathedral and has many precious objects of religious art.

- Pinacoteca Provinciale (Provincial Pinacotheca). Located inside the "Palazzo Pinto" in the "Via dei Mercanti" (Merchant street). It has many Renaissance paintings (like those of Andrea Sabatini, who worked in the Cappella Sistina).

Archaeological sites

- Area archeologica etrusco-sannitica di Fratte. The Archaeological site of the Etruscans and Samnites in Fratte is the most southern in Italy and is located in the eastern outskirts of Salerno. It has a huge necropolis.

Twin towns — Sister cities

Salerno is twinned with:

See also

- List of Princes of Salerno

- Principality of Salerno

- Schola Medica Salernitana

- Salerno railway station

- University of Salerno

- U.S. Salernitana 1919

- Operation Avalanche

- Salerno Cathedral

References

- ↑ "Bilancio demografico Anno 2014 (dati provvisori) Comune: Salerno". ISTAT (in Italian). 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Salerno - History, art and culture".

- ↑ Bairoch, Paul. Cities and Economic Development: From the Dawn of History to the Present. p. 161. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ↑ Carmine Pinto (13 December 2010). "La rivoluzione vittoriosa e la nascita di un nuovo Stato". la Città (in Italian). Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, "Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, 1870–1925".

- ↑ "Aggiornamento della carta dei vincoli" (PDF). comune.salerno.it (in Italian). 2011. p. 3. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ http://demo.istat.it/bil2007/index.html

- ↑ "Cittadini Stranieri. Bilancio demografico anno 2010 e popolazione residente al 31 Dicembre - Tutti i paesi di cittadinanza Comune: Salerno". ISTAT (in Italian). 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "Autorità Portuale di Salerno - Traffici Commerciali 2009-2013". porto.salerno.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "Metropolitana di Salerno". metrosalerno.com (in Italian). 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ↑ "Stazione Marittima di Salerno". http://www.livesalerno.com/it/ (in Italian). 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "A short history of the university". unisa.it. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "Anagrafe Nazionale Studenti - Iscritti 2012/2013". MIUR (in Italian). 7 March 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "Course organization". unisa.it. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ http://www.legaserieb.it/

- ↑ "I rioni del centro storico" (in Italian).

- ↑ "Gemellaggio tra Salerno e la città giapponese di Tono". comune.salerno.it (in Italian). 4 March 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "Salerno e Rouen unite da Linea d'ombra". la Repubblica (in Italian). 3 March 2004. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "SALERNO - DOMANI IMPORTANTE GEMELLAGGIO MEDICO-SPECIALISTICO". informazione.campania.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "La presentazione in occasione del gemellaggio Baltimora-Salerno. La struttura diretta da Fasano L' iniziativa". la Repubblica (in Italian). 16 December 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "Gemellaggio interculturale Salerno-Pazardzhik (Bulgaria)". comune.salerno.it (in Italian). 27 September 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "La Lega sbarca al sud. Scambio con Salerno". L'Arena (in Italian). 23 July 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

Bibliography

- Bonfanti, Giuseppe. Dalla Svolta di Salerno al 18 aprile 1948. Editrice La Scuola. Brescia 1979.

- Crisci, Generoso. Salerno sacra:ricerca storica. Edizioni della Curia arcivescovile. Salerno 1962.

- D'Episcopo, Francesco. Salerno. Sulla scia di Alfonso Gatto. Masuccio e l'Ottocento salernitano. Editrice Il Sapere. Ancona 2004.

- De Renzi, Salvatore. Storia documentata della Scuola Medica di Salerno. Tipografie Gaetano Nobile. Naples, 1857.

- Di Martino, Maristella. Le Ricette di Salerno. La cultura gastronomica della città. Editore Il Raggio di Luna. Salerno 2006.

- Errico, Ernesto. Cinquant'anni fa a Salerno. Ripostes Editore. Salerno 2004.

- Felici, Maria. Palazzi nobiliari a Salerno. Edizioni La Veglia. Salerno 1996.

- Giordano, Gaetano. Il Profeta della Grande Salerno. Cento anni di storia meridionale nei ricordi di Alfonso Menna. Avagliano Editore. Salerno 1999.

- Iannizzaro, Vincenzo. Salerno. La Cinta Muraria dai Romani agli Spagnoli. Editore Elea Press. Salerno 1999.

- Iovino, Giorgia. Riqualificazione urbana e sviluppo locale a Salerno. Attori, strumenti e risorse di una città in trasformazione. Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane. Naples, 2002.

- Mazzetti, Massimo. Salerno Capitale d'Italia. Edizioni del Paguro. Salerno 2000.

- Musi, Aurelio. Salerno moderna. Editore Avagliano. Salerno 1999.

- Ferraiolo Marco Storia di un anno di anni fa – Racconti di vita salernitana degli anni 60–70 . Edizioni Ripostes . Salerno 2005

- Roma, Adelia. I giardini di Salerno. Editore Elea Press. Salerno 1997.

- Seton-Watson, Christopher. Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, 1870–1925. John Murray Publishers. London, 1967.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salerno. |

- Photo of the "Cripta" of the Salerno Cathedral, where is the tomb of the Apostle Matthew

- Information about the city of Salerno (in Italian)

-

"Salerno". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

"Salerno". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|