Archbasilica of St. John Lateran

| Papal Archbasilica of Saint John in Lateran Major Papal and Roman Archbasilica of the Most Holy Savior and Saints John the Baptist and the Evangelist in Lateran Mother and Head of all churches in Rome and in the World (full name) | |

|---|---|

|

Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Rome, Italy[1] |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°53′9.26″N 12°30′22.16″E / 41.8859056°N 12.5061556°ECoordinates: 41°53′9.26″N 12°30′22.16″E / 41.8859056°N 12.5061556°E |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Rite | Latin Rite |

| Province | Rome |

| Year consecrated | AD 324 |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Papal major basilica |

| Leadership | Cardinal Agostino Vallini |

| Website | Official Site |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Alessandro Galilei |

| Architectural type | Cathedral |

| Architectural style | Baroque |

| Direction of façade | ENE |

| Groundbreaking | AD 4th Century |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 140 metres (460 ft) |

| Width | 140 metres (460 ft) |

| Width (nave) | 65 metres (213 ft) |

| Materials | Marble, granite, and cement |

The Papal Archbasilica of St. John in the Lateran (Italian: Arcibasilica Papale di San Giovanni in Laterano), commonly known as St. John Lateran Archbasilica, St. John Lateran Basilica, St. John Lateran, or just The Lateran Basilica, is the cathedral church of Rome and the official episcopal seat of the Bishop of Rome, the Roman Pontiff.

It is the oldest and ranks first among the five Papal Basilicas of the world and the four Major Basilicas of Rome (all of which are also Papal basilicas), being the oldest church in the West and having the Cathedra of the Bishop of Rome.[2][3] It has the title of ecumenical mother church among Roman Catholics. The current archpriest is Agostino Vallini, Cardinal Vicar General for the Diocese of Rome.[4] The President of the French Republic, currently François Hollande, is ex officio the "first and only honorary canon" of the Archbasilica, a title held by the heads of state of France since King Henry IV.

The large inscription on the façade reads in Latin: Clemens XII Pont Max Anno V Christo Salvatori In Hon SS Ioan Bapt et Evang; which a highly abbreviated inscription translated as "Pope Clement XII, in the fifth year of his reign, dedicated this building to Christ the Savior, in honor of Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist".[5] This is because the Archbasilica, as indicated by its full title (provided below) was originally dedicated to Christ the Savior, with the co-dedications to the two St. Johns being made centuries later. As the cathedral of the Bishop of Rome, it ranks above all other churches in the Catholic Church, including St. Peter's Basilica. For that reason, unlike all other Catholic basilicas, it is titled Archbasilica.

The Archbasilica is in the City of Rome, outside the boundaries of Vatican City which is approximately 4 km (2.5 mi) to the northwest, although the Archbasilica and its adjoining buildings enjoy extraterritorial status as one of the properties of the Holy See pursuant to the Lateran Treaty of 1929.[1]

Etymology

The Archbasilica's Latin name is Archibasilica Sanctissimi Salvatoris et Sanctorum Iohannes Baptista et Evangelista in Laterano, which translates in English as Archbasilica of the Most Holy Savior and Saints John the Baptist and the Evangelist in the Lateran and in Italian as Arcibasilica [Papale] del Santissimo Salvatore e Santi Giovanni Battista ed Evangelista in Laterano.[4]

Lateran Palace

The Archbasilica stands over the remains of the Castra Nova equitum singularium, the "New Fort of the Roman imperial cavalry bodyguards". The fort was established by Septimius Severus in AD 193. Following the victory of Emperor Constantine I over Maxentius (for whom the Equites singulares augusti, the emperor's mounted bodyguards had fought) at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the guard was abolished and the fort demolished. Substantial remains of the fort lie directly beneath the nave.

The remainder of the site was occupied during the early Roman Empire by the palace of the gens Laterani. Sextius Lateranus was the first plebeian to attain the rank of consul, and the Laterani served as administrators for several emperors. One of the Laterani, Consul-designate Plautius Lateranus, became famous for being accused by Nero of conspiracy against the Emperor. The accusation resulted in the confiscation and redistribution of his properties.

The Lateran Palace fell into the hands of the Emperor when Constantine I married his second wife Fausta, sister of Maxentius. Known by that time as the "Domus Faustae" or "House of Fausta," the Lateran Palace was eventually given to the Bishop of Rome by Constantine I. The actual date of the donation is unknown, but scholars speculate that it was during the pontificate of Pope Miltiades, in time to host a synod of bishops in 313 that was convened to challenge the Donatist schism, declaring Donatism to be heresy. The palace basilica was converted and extended, becoming the residence of Pope St. Silvester I, eventually becoming the Cathedral of Rome, the seat of the Popes qua the Bishops of Rome.[6]

The Middle Ages

The official dedication of the Archbasilica and the adjacent Lateran Palace was presided over by Pope Sylvester I in 324, declaring both to be a Domus Dei or "House of God." The Papal Cathedra was placed in its interior, making it the Cathedral of the Bishop of Rome. In reflection of the Archbasilica's claim to primacy in the world as "mother church", the words Sacrosancta Lateranensis ecclesia omnium urbis et orbis ecclesiarum mater et caput (translated as "Most Holy Lateran Church, of all the churches in the City and the world, the mother and head") are inscribed in the front wall between the main entrance doors.

The Archbasilica and Lateran Palace have been rededicated twice. Pope Sergius III dedicated them to St. John the Baptist in the 10th century in honor of the newly consecrated baptistry of the Archbasilica. Pope Lucius II dedicated them both to St. John the Evangelist in the 12th century. Thus, St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist are regarded as co-patrons of the Cathedral, with the primary patron being Christ the Savior Himself, as the inscription in the entrance of the Archbasilica indicates and as is traditional in the patriarchal cathedrals.

Thus, the Archbasilica remains dedicated to the Savior, and its titular feast is the Feast of the Transfiguration. The Archbasilica became the most important shrine of the two St. Johns, albeit not often jointly venerated. In later years, a Benedictine monastery was established at the Lateran Palace, devoted to serving the Archbasilica and the two Saints.

Every pope beginning with Pope Miltiades occupied the Lateran Palace, until the reign of the French Pope Clement V, who in 1309 decided to transfer the official seat of the Catholic Church to Avignon, a Papal fiefdom that was an enclave within France. The Lateran Palace has also been the site of five ecumenical councils (see Lateran Councils).

Lateran Fires

During the time the Papacy was seated in Avignon, France, the Lateran Palace and the Archbasilica began to deteriorate. Two destructive fires ravaged them in 1307 and 1361. After both fires the Pope in Avignon sent money to pay for their reconstruction and maintenance. Despite those expenditures the Archbasilica and the Lateran Palace lost their former splendor.

When the Papacy returned from Avignon and the Pope again resided in Rome, the Archbasilica and the Lateran Palace were deemed inadequate considering the accumulated damage. The Popes took up residence at the Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere and later at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. Eventually, the Palace of the Vatican was built adjacent to the Basilica of St. Peter, which already existed since the time of Emperor Constantine I, and the Popes began to reside there, and continue to reside there to this day, with the exception of Pope Francis who resides elsewhere in Vatican City.

Reconstruction

There were several attempts at reconstruction of the Archbasilica before a definitive program of Pope Sixtus V. Sixtus V hired his favorite architect, Domenico Fontana to supervise much of the project. The original Lateran Palace was demolished and replaced with a new edifice. On the square in front of the Lateran Palace is the largest standing obelisk in the world, known as the Lateran Obelisk. It weighs an estimated 455 tons. It was commissioned by the Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III and erected by Thutmose IV before the great Karnak temple of Thebes, Egypt. Intended by Emperor Constantine I to be shipped to Constantinople, the very preoccupied Constantius II had it shipped instead to Rome, where it was erected in the Circus Maximus in AD 357. At some time it broke and was buried under the Circus. In the 16th century it was discovered and excavated, and Sixtus V had it re-erected on a new pedestal on 3 August 1588 at its present site.[7][8][9]

Further renovation of the interior of the Archbasilica ensued under the direction of Francesco Borromini, commissioned by Pope Innocent X. The twelve niches created by his architectural scheme were eventually filled in 1718 with statues of the Apostles, sculpted by the most prominent Roman Rococo sculptors.

The vision of Pope Clement XII for reconstruction was an ambitious one in which he launched a competition to design a new façade. More than 23 architects competed, mostly working in the then-current Baroque idiom. The putatively impartial jury was chaired by Sebastiano Conca, president of the Roman Academy of Saint Luke. The winner of the competition was Alessandro Galilei.

The façade as it appears today was completed in 1735. It reads in Latin: Clemens XII Pont Max Anno V Christo Salvatori In Hon SS Ioan Bapt et Evang; this highly abbreviated inscription is expanded thus: Clemens XII, Pont[ifex] Max[imus], [in] Anno V, [dedicavit hoc aedificium] Christo Salvatori, in hon[orem] [sanctorum] Ioan[is] Bapt[tistae] et Evang[elistae]. This translates as "Pope Clement XII, in the fifth year of his reign, dedicated this building to Christ the Savior, in honor of Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist".[5] Galilei's façade removed all vestiges of traditional, ancient, basilical architecture and imparted a neo-classical facade.

-

Nave.

-

Ceiling.

-

The Lateran Obelisk in its third location, in front of the Lateran Palace.

-

The Loggia delle Benedizioni, on the rear left side. Annexed, on the left, is the Lateran Palace.

World War II

During the Second World War, the Lateran and its related buildings provided a safe haven from the Nazis and Italian Fascists for numbers of Jews and other refugees. Among those who found shelter there were Meuccio Ruini, Alcide De Gasperi, Pietro Nenni and others. The Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul and the sixty orphan refugees they cared for were ordered to leave their convent on the Via Carlo Emanuele. The Sisters of Maria Bambina, who staffed the kitchen at the Pontifical Major Roman Seminary at the Lateran offered a wing of their convent. The grounds also housed Italian soldiers.[10]

Fathers Vincenzo Fagiolo and Pietro Palazzini, vice-rector of the seminary, were recognized by Yad Vashem for their efforts to assistance Jews.[11][12]

Architectural History

An apse lined with mosaics and open to the air still preserves the memory of one of the most famous halls of the ancient palace, the "Triclinium" of Pope Leo III, which was the state banqueting hall. The existing structure is not ancient, but some portions of the original mosaics may have been preserved in the tripartite mosaic of its niche. In the center Christ gives to the Apostles their mission; on the left He gives the Keys of the Kingdom of Heaven to Pope St. Sylvester and the Labarum to Emperor Constantine I; and on the right Pope St. Peter gives the Papal stole to Pope Leo III and the standard to Emperor Charlemagne of the Holy Roman Empire.

Some few remains of the original buildings may still be traced in the city walls outside the Gate of St. John, and a large wall decorated with paintings was uncovered in the 18th century within the Archbasilica behind the Lancellotti Chapel. A few traces of older buildings were also revealed during the excavations of 1880, when the work of extending the apse was in progress, but nothing of importance was published.

A great many donations from the Popes and other benefactors to the Archbasilica are recorded in the Liber Pontificalis, and its splendor at an early period was such that it became known as the "Basilica Aurea", or "Golden Basilica". This splendor drew upon it the attack of the Vandals, who stripped it of all its treasures. Pope Leo I restored it around AD 460, and it was again restored by Pope Hadrian.

In 897, it was almost totally destroyed by an earthquake: ab altari usque ad portas cecidit ("it collapsed from the altar to the doors"). The damage was so extensive that it was difficult to trace the lines of the old building, but these were mostly respected and the new building was of the same dimensions as the old. This second basilica stood for 400 years before it burned in 1308. It was rebuilt by Pope Clement V and Pope John XXII. It burned once more in 1360, and was rebuilt by Pope Urban V.

Through vicissitudes the Archbasilica retained its ancient form, being divided by rows of columns into aisles, and having in front a peristyle surrounded by colonnades with a fountain in the middle, the conventional Late Antique format that was also followed by the old St. Peter's Basilica. The façade had three windows and was embellished with a mosaic representing Christ as the Savior of the world.

The porticoes were frescoed, probably not earlier than the 12th century, commemorating the Roman fleet under Vespasian, the taking of Jerusalem, the Baptism of Emperor Constantine I and his "Donation" of the Papal States to the Catholic Church. Inside the Archbasilica the columns no doubt ran, as in all other basilicas of the same date, the whole length of the church, from east to west.

In one of the rebuildings, probably that which was carried out by Pope Clement V, a transverse nave was introduced, imitated no doubt from the one which had been added, long before this, to the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls. Probably at this time the Archbasilica was enlarged.

Some portions of the older buildings survive. Among them the pavement of mediaeval Cosmatesque work, and the statues of St. Peter and St. Paul, now in the cloister. The graceful baldacchino over the high altar, which looks out of place in its present surroundings, dates from 1369. The stercoraria, or throne of red marble on which the Popes sat, is now in the Vatican Museums. It owes its unsavory name to the anthem sung at previous Papal coronations, "De stercore erigens pauperem" ("lifting up the poor out of the dunghill", from Psalm 112).

From the 5th century, there were seven oratories surrounding the Archbasilica. These before long were incorporated into the church. The devotion of visiting these oratories, which was maintained through the Mediaeval Ages, gave rise to the similar devotion of the seven altars, still common in many churches of Rome and elsewhere.

Of the façade by Alessandro Galilei (1735), the cliché assessment has ever been that it is the façade of a palace, not of a church. Galilei's front, which is a screen across the older front creating a narthex or vestibule, does express the nave and double aisles of the Archbasilica, which required a central bay wider than the rest of the sequence. Galilei provided it, without abandoning the range of identical arch-headed openings, by extending the central window by flanking columns that support the arch, in the familiar Serlian motif.

By bringing the central bay forward very slightly, and capping it with a pediment that breaks into the roof balustrade, Galilei provided an entrance doorway on a more than colossal scale, framed in the paired colossal Corinthian pilasters that tie together the façade in the manner introduced at Michelangelo's palace on the Campidoglio.

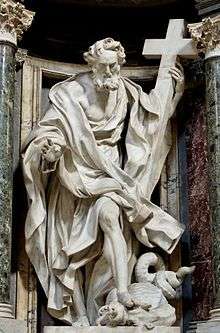

Statues of the Apostles

The twelve niches created in Francesco Borromini's architecture were left vacant for decades. When in 1702 Pope Clement XI and Benedetto Cardinal Pamphili, archpriests of the Archbasilica, announced their grand scheme for twelve sculptures of the Apostles, of greater than life-size, to fill the niches, the commission was opened to all the premier sculptors of late Baroque Rome.[13] Each statue was to be sponsored by an illustrious prince with the Pope himself sponsoring that of St. Peter and Cardinal Pamphili that of St. John the Evangelist. Most of the sculptors were given a sketch drawn by Pope Clement's favorite painter, Carlo Maratta, to which they were to adhere, but with the notable exception being Pierre Le Gros the Younger, who successfully refused to sculpt to Maratta's design and consequently was not given a sketch.[14]

The sculptors and their sculptures follow and are dated according to Conforti:

- Francesco Moratti

- St. Simon (1704–09)

- St. Jude Thaddeus (1704–09)

- St. Philip (1705–11)

- St. Thomas (1705–11)

- St. Bartholomew (c. 1705–12)

- St. James the Lesser (1705–11)

- St. Andrew (1705–09)

- St. John (1705–11)

- St. Matthew (1711–15)

- St. James the Greater (1715–18)

-

St. Bartholomew by Le Gros

-

St. James the Greater by Rusconi

-

St. Paul by Monnot

-

Pope St. Peter by Monnot

-

St. Simon by Moratti

-

St. Jude Thaddeaus by Ottoni

-

St. Philip by Mazzuoli

-

St. Thomas by Le Gros

-

St. James the Lesser by de' Rossi

-

St. Andrew by Rusconi

-

St. John by Rusconi

-

St. Matthew by Rusconi

Papal Tombs

There are six extant Papal tombs inside the Archbasilica: Alexander III (right aisles), Pope Sergius IV (right aisles), Pope Clement XII Corsini (left aisle), Pope Martin V (in front of the confessio); Pope Innocent III (right transept); and Pope Leo XIII (left transept), by G. Tadolini (1907). The last of these, Pope Leo XIII, was the last Pope not to be entombed in St. Peter's Basilica.

Twelve additional Papal tombs were constructed in the Archbasilica starting in the 10th century, but were destroyed during the two fires that ravaged it in 1308 and 61. The remains of these charred tombs were gathered and reburied in a polyandrum. The Popes whose tombs were destroyed are: Pope John X (914–28), Pope Agapetus II (946–55), Pope John XII (955–64), Pope Paschal II (1099–1118), Pope Callixtus II (1119–24), Pope Honorius II (1124–30), Pope Celestine II (1143–4), Pope Lucius II (1144–5), Pope Anastasius IV (1153–4), Pope Clement III (1187–91), Pope Celestine III (1191–8), and Pope Innocent V (1276). Popes who reigned during this period, whose tombs are unknown, and who may have been buried in the Archbasilica include Pope John XVII (1003), Pope John XVIII (1003–9), and Pope Alexander II (1061–73). Pope John X was the first pope buried within the walls of Rome, and was granted a prominent burial due to rumors that he was murdered by Theodora during a historical period known as the Pornocracy. Cardinals Vincenzo Santucci and Carlo Colonna are also buried in the Archbasilica.

Lateran Cloister

Between the Archbasilica and the City wall there was in former times a great monastery, in which dwelt the community of monks whose duty it was to provide the services in the Archbasilica. The only part of it which still survives is the 13th century cloister, surrounded by graceful, twisted columns of inlaid marble. They are of a style intermediate between the Romanesque proper and the Gothic, and are the work of Vassellectus and the Cosmati.

Lateran Baptistery

The octagonal Lateran Baptistery stands somewhat apart from the Archbasilica. It was founded by Pope Sixtus III, perhaps on an earlier structure, for a legend arose that Emperor Constantine I was baptized there and enriched the edifice. The Baptistery was for many generations the only baptistery in Rome, and its octagonal structure, centered upon the large basin for full immersions, provided a model for others throughout Italy, and even an iconic motif of illuminated manuscripts known as "the fountain of life".

Holy Stairs

The Scala Sancta, or Holy Stairs, are white marble steps encased in wooden ones. According to Catholic Tradition, they form the staircase which once led to the praetorium of Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem and which, therefore, were sanctified by the footsteps of Jesus Christ during His Passion. The marble stairs are visible through openings in the wooden risers. Their translation from Jerusalem to the Lateran Palace in the 4th century is credited to St. Empress Helena, the mother of the then-Emperor Constantine I. In 1589 Pope Sixtus V relocated the steps to their present location in front of the ancient palatine chapel named the Sancta Sanctorum. Ferraù Fenzoni completed some of the frescoes on the walls.

Feast of the Dedication of the Archbasilica

In the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church, 9 November is the feast of the Dedication of the (Arch)Basilica of the Lateran (Dedicatio Basilicae Lateranensis), and is referred to in older texts as the "Dedication of the Basilica of the Holy Savior". In view of its role as the mother church of the world, this liturgical day is celebrated worldwide as a "feast" and not a "memorial" as might be expected.

Archpriests

Pope Boniface VIII instituted the office of Archpriest of the Archbasilica circa 1299.[15]

List of Archpriests of the Archbasilica:[16]

|

|

Gallery

-

Alessandro Galilei completed the late Baroque façade of the Archbasilica in 1735 after winning a competition for the design.

-

Next to the main entrance is the inscription of the Archbasilica's claim to being the mother church of the world.

-

Statue of St. John the Baptist.

-

The decorated ceiling.

-

Apse depicting mosaics from the Triclinium of Pope Leo III in the ancient Lateran Palace.

-

The cloister of the attached monastery, with a cosmatesque decoration.

-

The cloister of the attached monastery.

-

Our Lady of Częstochowa depicted in the Archbasilica.

See also

- Early Christian art and architecture

- Index of Vatican City-related articles

- Colegio de San Juan de Letran, a Philippine school named after the Archbasilica.

Notes and References

- 1 2 The Archbasilica is within Italian territory and not the territory of the Vatican City State. (Lateran Treaty of 1929, Article 15 (The Treaty of the Lateran by Benedict Williamson; London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne Limited, 1929; pages 42–66)) However, the Holy See fully owns the Archbasilica, and Italy is legally obligated to recognize its full ownership thereof (Lateran Treaty of 1929, Article 13 (Ibidem)) and to concede to it "the immunity granted by International Law to the headquarters of the diplomatic agents of foreign States" (Lateran Treaty of 1929, Article 15 (Ibidem)).

- ↑ "San Giovanni in Laterano" (in Italian). vatican.va. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ↑ Pope Benedict XVI's theological act of renouncing the title of "Patriarch of the West" had as a consequence that the "patriarchal basilicas" are now officially known as "Papal basilicas.

- 1 2 "Basilica Papale" (in Italian). Vicariatus Urbis: Portal of the Diocese of Rome. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- 1 2 Landsford, Tyler (2009). The Latin Inscriptions of Rome: A Walking Guide. JHU Press. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Arcibasilica Papale San Giovanni in Laterano – Cenni storici" (in Italian). Holy See. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ Fanny Davenport and Rogers MacVeagh, Fountains of Papal Rome (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1915), pp. 156 et seq.

- ↑ Lunde, Paul (March–April 1979). "A Forest of Obelisks". Saudi Aramco World (Houston, Texas: Aramco Services Company). pp. 28–32. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ PBS:NOVA:A World of Obelisks-Rome

- ↑ Marchione, Margherita. Yours Is a Precious Witness: Memoirs of Jews and Catholics in Wartime Italy, Paulist Press, 2001, ISBN 9780809140329

- ↑ "Palazzini", the righteous among the Nations, Yad Vashem

- ↑ "Fagiolo", The Righteous Among the Nations, Yad Vashem

- ↑ "The largest sculptural task in Rome during the early eighteenth century," per Rudolph Wittkower, Art and Architecture in Italy, 1600–1750, Revised Edition, 1965, p. 290, provides that "the distribution for commissions is, at the same time, a good yardstick for measuring the reputation of contemporary sculptors."

- ↑ Cf. Michael Conforti, The Lateran Apostles, unpublished Ph. D. thesis (Harvard University, 1977); Conforti published a short resume of his dissertation: Planning the Lateran Apostles, in Henry A. Millon (editor), Studies in Italian Art and Architecture 15th through 18th Centuries, (Rome, 1980) (Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 35), pp. 243–60.

- ↑ Moroni, Gaetano (1840–61). Dizionario di Erudizione Storico–Ecclesiastica da S. Pietro sino ai Nostri Giorni (in Italian) 12. Venezia: Tipografia Emiliana. p. 31.

- ↑ Respective biographic entries in "Essay of a General List of Cardinals". The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church..

- Bibliography

-

Barnes, Arthur S. (1913). "Saint John Lateran". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Barnes, Arthur S. (1913). "Saint John Lateran". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Claussen, Peter C.; Senekovic, Darko (2008). S. Giovanni in Laterano. Mit einem Beitrag von Darko Senekovic über S. Giovanni in Fonte, in Corpus Cosmatorum, Volume 2, 2. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-09073-8.

- Krautheimer, Richard; Frazer, Alfred; Corbett, Spencer (1937–77). Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae: The Early Christian Basilicas of Rome (IV–IX Centuries). Vatican City: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana (Pontifical Institute of Christian Archaeology). OCLC 163156460.

- Webb, Matilda (2001). The Churches and Catacombs of Early Christian Rome. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. p. 41. ISBN 1-902210-57-3.

- Lenski, Noel (2006). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 282. ISBN 0-521-52157-2.

- Stato della Città del Vaticano (2009). "Arcibasilica Papale Di San Giovanni In Laterano" (in Italian). Holy See. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

External links

- High-resolution virtual tour of St. John Lateran, from the Vatican.

- Satellite Photo of St. John Lateran

- Constantine's obelisk

- San Giovanni in Laterano

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|