Welsh English

| Welsh English | |

|---|---|

| Native to | United Kingdom |

| Region | Wales |

Native speakers | 2.5 million (date missing) |

| Latin (English alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Welsh English, Anglo-Welsh, or Wenglish refers to the dialects of English spoken in Wales by Welsh people. The dialects are significantly influenced by Welsh grammar and often include words derived from Welsh. In addition to the distinctive words and grammar, a variety of accents are found across Wales, including those of north Wales, the Cardiff dialect, the South Wales Valleys and west Wales.

In the east and south east, it has been influenced by West Country dialects due to immigration, while in North Wales, the influence of Merseyside English is becoming increasingly prominent.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Wales |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

|

Traditions

|

|

Mythology and folklore |

| Religion |

| Art |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Monuments |

|

Pronunciation

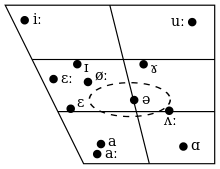

Vowels

Short monophthongs

- The vowel of cat /æ/ is pronounced as a more central near-open front unrounded vowel [æ̈].[1] In Cardiff, bag is pronounced with a long vowel [aː].[2] In Powys, a pronunciation resembling its New Zealand and South African analogue is sometimes heard, i.e. trap is pronounced /trɛp/[3]

- The vowel of end /ɛ/ is a more open vowel and thus closer to cardinal vowel [ɛ] than RP[1]

- The vowel of "kit" /ɪ/ often sounds closer to the schwa sound of above, an advanced close-mid central unrounded vowel [ɘ̟][1]

- The vowel of hot /ɒ/ is raised towards /ɔ/ and can thus be transcribed as [ɒ̝] or [ɔ̞][1]

- The vowel of "bus" /ʌ/ is pronounced [ɜ][4] and is encountered as a hypercorrection in northern areas for foot.[3] It is sometimes manifested in border areas of north and mid Wales as an open front unrounded vowel /a/ or as a near-close near-back rounded vowel /ʊ/ in northeast Wales, under influence of Cheshire and Merseyside accents.[3]

- In accents that distinguish between foot and strut, the vowel of foot is a more lowered vowel [ɤ̈],[4] particularly in the north[3]

- The schwa of better may be different from that of above in some accents; the former may be pronounced as [ɜ], the same vowel as that of bus[1]

- The schwi tends to be supplanted by an /ɛ/ in final closed syllables, e.g. brightest /ˈbɾəi.tɛst/. The uncertainty over which vowel to use often leads to 'hypercorrections' involving the schwa, e.g. programme is often pronounced /ˈproː.ɡrəm/[2]

Long monophthongs

- The vowel of car is often pronounced as a open central unrounded vowel [ɑ̈][5] and more often as a long open front unrounded vowel /aː/[3]

- In broader varieties, particularly in Cardiff, the vowel of bird is similar to South African and New Zealand, i.e. a lowered close-mid front rounded vowel [ø̞][6]

- Most other long monophthongs are similar to that of Received Pronunciation, but words with the RP /əʊ/ are sometimes pronounced as [oː] and the RP /eɪ/ as [eː]. An example that illustrates this tendency is the Abercrave pronunciation of play-place [ˈpleɪˌpleːs][7]

- In northern varieties, /əʊ/ as in coat and /ɔː/ as in caught/court may be merged into /ɔː/ (phonetically [oː]).[2]

- In Rhymney, the diphthong of there is monophthongised [ɛː][8]

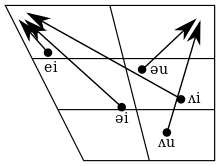

Diphthongs

- Fronting diphthongs tend to resemble Received Pronunciation, apart from the vowel of bite that has a more centralised onset [æ̈ɪ][7]

- Backing diphthongs are more varied:[7]

- The vowel of low in RP, other than being rendered as a monophthong, like described above, is often pronounced as [oʊ̝]

- The word town is pronounced similarly to the New Zealand pronunciation of tone, i.e. with a near-open central onset [ɐʊ̝]

- The /juː/ of RP in the word due is usually pronounced as a true diphthong [ëʊ̝]

Correspondence between the IPA help key and Welsh English vowels Pure vowels Help key Welsh Examples /ɪ/ /ɪ/ ~ /ɪ̈/ ~ /ɘ/ bid, pit /iː/ /i/ bead, peat /ɛ/ /ɛ/ bed, pet /eɪ/ /e/~/eɪ/ fate, gate /eɪ/ bay, hey /æ/ /a/ bad, pat, barrow, marry /ɑː/ /aː/ balm, father, pa /ɒ/ /ɒ/ bod, pot, cot /ɔː/ /ɒː/ bawd, paw, caught /oʊ/ /o/~/oʊ/ beau, hoe, poke /oʊ/ soul,low,tow /ʊ/ /ʊ/ good, foot, put /uː/ /uː/ booed, food /ʌ/ /ə/~/ʊ/ bud, putt Diphthongs /aɪ/ /aɪ/ ~ /əɪ/ buy, ride, write /aʊ/ /aʊ̝/ ~ /əʊ̝/~ /ɐʊ̝/ how, pout /ɔɪ/ /ɒɪ/ boy, hoy /juː/ /ɪu/~/ëʊ̝/ hue, pew, new R-coloured vowels /ɪər/ /ɪə̯(ɾ)/ beer, mere /ɛər/ /ɛə̯(ɾ)/ bear, mare, Mary /ɑr/ /aː(ɾ)/ bar, mar /ɔr/ /ɒː(ɾ)/ moral, forage,born, for /ɔər/ /oː(ɾ)/ boar, four, more /ʊər/ /ʊə̯(ɾ)/ boor, moor /ɜr/ /ɜː/~/øː/ bird, herd, furry /ər/ (ɚ) /ə(ɾ)/ runner, mercer

Consonants

- A strong tendency (shared with Scottish English and some South African accents) towards using an alveolar tap [ɾ] (a 'tapped r') in place of an approximant [ɹ] (the r used in most accents in England).[9]

- Rhoticity is largely uncommon, apart from some speakers in Port Talbot who supplant the front vowel of bird with /ɚ/, like in many varieties of North American English[10] and accents influenced by Welsh[10]

- Some gemination between vowels is often encountered, e.g. money is pronounced [ˈmɜ.nːiː][11]

- In northern varieties influenced by Welsh, pens and pence merge into /pɛns/ and chin and gin into /dʒɪn/[11]

- In the north-east, under influence of such accents as Scouse, ng-coalescence does not take place, so sing is pronounced /sɪŋɡ/[12]

- Also in northern accents, /l/ is frequently strongly velarised [ɫː]. In much of the south-east, clear and dark L alternate much like they do in RP[10]

- The consonants are generally the same as RP but Welsh consonants like [ɬ] and [x] are encountered in loan words such as Llangefni and Harlech[11]

Distinctive vocabulary and grammar

Aside from lexical borrowings from Welsh like bach (little, wee), eisteddfod, nain and taid (grandmother and grandfather respectively), there exist distinctive grammatical conventions in vernacular Welsh English. Examples of this include the use by some speakers of the tag question isn't it? regardless of the form of the preceding statement and the placement of the subject and the verb after the predicate for emphasis, e.g. Fed up, I am or Running on Friday, he is.[11]

In South Wales the word "where" may often be expanded to "where to", as in the question, "Where to is your Mam?". The word "butty" ("byti" in Welsh orthography, probably related to "buddy") is used to mean "friend" or "mate"[13]

There is no standard variety of English that is specific to Wales, but such features are readily recognised by Anglophones from the rest of the UK as being from Wales, including the (actually rarely used) phrase look you which is a translation of a Welsh language tag.[11]

The word "tidy" has been described as "One of the most over-worked Wenglish words" and can have a range of meanings including - fine or splendid, long, decent, and plenty or large amount. A "tidy swill" is a wash involving at least face and hands.[14]

Orthography

Spellings are almost identical to other dialects of British English. Minor differences occur with words descended from Welsh that are not anglicised unlike in many other dialects of English.

In Wales, the valley is always "cwm", not the Anglicised version "coombe". As with other dialects of British English, -ise endings are preferred: "realise" instead of "realize". However, both forms are acceptable.

History of the English language in Wales

The presence of English in Wales intensified on the passing of the Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–1542, the statutes having promoted the dominance of English in Wales; this, coupled with the closure of the monasteries, which closed down many centres of Welsh education, led to decline in the use of the Welsh language.

The decline of Welsh and the ascendancy of English was intensified further during the Industrial Revolution, when many Welsh speakers moved to England to find work and the recently developed mining and smelting industries came to be manned by Anglophones. David Crystal, who grew up in Holyhead, claims that the continuing dominance of English in Wales is little different from its spread elsewhere in the world.[15]

Influence outside Wales

While other British English accents have affected the accents of English in Wales, influence has moved in both directions. In particular, Scouse and Brummie (colloquial) accents have both had extensive Anglo-Welsh input through migration, although in the former case, the influence of Anglo-Irish is better known.

Literature

"Anglo-Welsh literature" and "Welsh writing in English" are terms used to describe works written in the English language by Welsh writers. It has been recognised as a distinctive entity only since the 20th century.[16] The need for a separate identity for this kind of writing arose because of the parallel development of modern Welsh-language literature; as such it is perhaps the youngest branch of English-language literature in the British Isles.

While Raymond Garlick discovered sixty-nine Welsh men and women who wrote in English prior to the twentieth century,[16] Dafydd Johnston thinks it "debatable whether such writers belong to a recognisable Anglo-Welsh literature, as opposed to English literature in general".[17] Well into the nineteenth century English was spoken by relatively few in Wales, and prior to the early twentieth century there are only three major Welsh-born writers who wrote in the English language: George Herbert (1593–1633) from Montgomeryshire, Henry Vaughan (1622–1695) from Brecknockshire, and John Dyer (1699–1757) from Carmarthenshire.

Welsh writing in English might be said to begin with the fifteenth-century bard Ieuan ap Hywel Swrdwal (?1430 - ?1480), whose Hymn to the Virgin was written at Oxford in England in about 1470 and uses a Welsh poetic form, the awdl, and Welsh orthography; for example:

- O mighti ladi, owr leding - tw haf

- At hefn owr abeiding:

- Yntw ddy ffast eferlasting

- I set a braents ws tw bring.

A rival claim for the first Welsh writer to use English creatively is made for the poet, John Clanvowe (1341–1391).

The influence of Welsh English can be seen in My People by Caradoc Evans, which uses it in dialogue (but not narrative); Under Milkwood by Dylan Thomas, originally a radio play; and Niall Griffiths whose gritty realist pieces are mostly written in Welsh English.

Popular culture

In the Iconic UK-TV series Thomas & Friends, the Narrow Gauge Engines Skarloey, Rheneas, Sir Handel, Peter Sam and Duke speak with Welsh Dialect, as do the two characters Merrick and Owen.

See also

- Cardiff accent and dialect

- Welsh literature in English

- Regional accents of English speakers

- Gallo (Brittany)

- Scots language

Other English dialects heavily influenced by Celtic languages

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- 1 2 3 "Accents of English: - John C. Wells - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- 1 2 "English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- ↑ "English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- ↑ "English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- 1 2 3 "English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- ↑ Paul Heggarty. "Sound Comparisons". Sound Comparisons. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- ↑ "English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- 1 2 3 "English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, pp. 335

- ↑ "Accents of English: - John C. Wells - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- ↑ "Why butty rarely leaves Wales". Wales Online. 2006-10-02. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- ↑

- ↑ Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, p. 334

- 1 2 Raymond Garlick An Introduction to Anglo-Welsh Literature (University of Wales Press, 1970)

- ↑ A Pocket Guide to the Literature of Wales University of Wales Press: Cardiff, 1994, p. 91

Bibliography

- Coupland, Nikolas (1990), English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change, ISBN 1-85359-032-0

Further reading

- Penhallurick, Robert (2004), "Welsh English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 98–112, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Podhovnik, Edith (2010), "Age and Accent - Changes in a Southern Welsh English Accent" (PDF), Research in Language 8: 1–18, doi:10.2478/v10015-010-0006-5, ISSN 2083-4616

External links

- Sounds Familiar? – Listen to examples of regional accents and dialects from across the UK on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website

- Talk Tidy : John Edwards, Author of books and CDs on the subject "Wenglish".

- Some thoughts and notes on the English of south Wales : D Parry-Jones, National Library of Wales journal 1974 Winter, volume XVIII/4

- Samples of Welsh Dialect(s)/Accent(s)

- Welsh vowels