SMS Grosser Kurfürst (1875)

- For the battleship of the same name, see SMS Grosser Kurfürst

SMS Grosser Kurfürst underway on her maiden voyage | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | SMS Grosser Kurfürst |

| Builder: | Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven |

| Laid down: | 1869 |

| Launched: | 17 September 1875 |

| Commissioned: | 6 May 1878 |

| Fate: | Accidentally rammed and sunk by SMS König Wilhelm 31 May 1878 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Preussen-class ironclad |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 96.59 m (316 ft 11 in) |

| Beam: | 16.30 m (53 ft 6 in) |

| Draft: | 7.11 m (23 ft 4 in) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Sail plan: | Full-rigged ship |

| Speed: | 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Range: | 1,690 nmi (3,130 km) at 10 kn (19 km/h) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

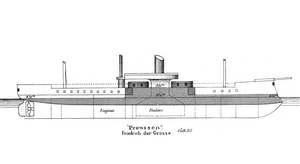

SMS Grosser Kurfürst [lower-alpha 1] (or Großer [lower-alpha 2]) was an ironclad turret ship of the German Kaiserliche Marine. She was laid down at the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven in 1870 and completed in 1878; her long construction time was in part due to a redesign that was completed after work on the ship had begun. Her main battery of four 26 cm (10 in) guns was initially to be placed in a central armored battery, but during the redesign this was altered to a pair of twin gun turrets amidships.

Grosser Kurfürst was sunk on her maiden voyage in an accidental collision with the ironclad SMS König Wilhelm. The two ships, along with SMS Preussen were steaming in the English Channel on 31 May 1878. The three ships encountered a group of fishing boats, and in turning to avoid them, Grosser Kurfürst inadvertently crossed too closely to König Wilhelm. The latter rammed Grosser Kurfürst, which sank in the span of about eight minutes, taking between 269 and 276 of her crew with her. Her loss spurred a series of investigations into the circumstances of the collision, which ultimately resulted in the acquittal of both Rear Admiral Carl Ferdinand Batsch, the squadron commander, and Count Alexander von Monts, the captain of Grosser Kurfürst. Political infighting over the affair led to the ousting of Rear Admiral Reinhold von Werner from the navy.

Construction

Grosser Kurfürst was ordered by the Imperial Navy from the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven; her keel was laid in 1869 under construction number 2.[1] The ship was launched on 17 September 1875 and commissioned into the German fleet on 6 May 1878.[2] Grosser Kurfürst cost the German government 7,303,000 gold marks.[1] As designed, Grosser Kurfürst was to have had her primary armament arranged in a central battery; after she was laid down, she was altered to mount her main guns in a pair of twin turrets. Although she was the first ship in her class of three vessels to be laid down, she was the last to be launched and commissioned. This was because she was redesigned after work had begun, and she was built by the newly established Imperial Dockyard. Her sister Preussen was built by an experienced commercial ship builder, and Friedrich der Grosse was laid down after the redesign was completed.[3]

The ship was 96.59 meters (316.9 ft) long overall and had a beam of 16.30 m (53.5 ft) and a draft of 7.12 m (23.4 ft) forward.[1] Grosser Kurfürst was powered by one 3-cylinder single expansion steam engine, which was supplied with steam by six coal-fired transverse trunk boilers. The ship's top speed was 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph), at 5,468 indicated horsepower (4,077 kW). She was also equipped with a full ship rig. Her standard complement consisted of 46 officers and 454 enlisted men.[4]

She was armed with four 26 cm (10 in) L/22 guns mounted in a pair of gun turrets placed amidships.[lower-alpha 3] As built, the ship was also equipped with two 17 cm (6.7 in) L/25 guns.[2] Grosser Kurfürst's armor was made of wrought iron and backed with teak. The armored belt was arrayed in two strakes. The upper strake was 203 mm (8.0 in) thick; the lower strake ranged in thickness from 102 to 229 mm (4.0 to 9.0 in). Both were backed with 234 to 260 mm (9.2 to 10.2 in) of teak. The gun turrets were protected by 203 to 254 mm (8.0 to 10.0 in) armor on the sides, backed by 260 mm of teak.[1]

Service history

Collision and loss

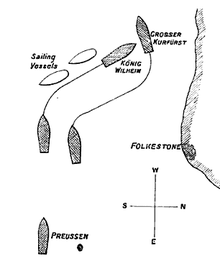

In April 1878, the armored squadron was reactivated for the annual summer training cycle, under the command of Rear Admiral Carl Ferdinand Batsch. Grosser Kurfürst joined the unit, which included her sisters Preussen and Friedrich der Grosse and the large ironclad König Wilhelm, after her commissioning on 6 May. A grounding by Friedrich der Grosse caused serious damage to her hull and prevented her from taking part in the upcoming training cruise. The three ships left Wilhelmshaven on the 29th.[5] König Wilhelm and Preussen steamed in a line, with Grosser Kurfürst off to starboard. On the morning of the 31st, the three ships encountered a pair of sailing vessels off Folkestone. Grosser Kurfürst turned to port to avoid the boats while König Wilhelm sought to pass the two boats, but there was not enough distance between her and Grosser Kurfürst. She therefore turned hard to port to avoid Grosser Kurfürst, but the action was not taken quickly enough, and König Wilhelm found herself pointed directly at Grosser Kurfürst.[6] König Wilhelm's ram bow tore a hole in Grosser Kurfürst.[7]

A failure to adequately seal the watertight bulkheads aboard Grosser Kurfürst caused the ship to sink rapidly,[2] in the span of about eight minutes.[6] Figures for the number of fatalities vary. Erich Gröner reports that out of a crew of 500 men, 269 died in the accident,[2] while Lawrence Sondhaus states that 276 men were killed.[5] Many of the bodies ended up in Cheriton Road Cemetery, where there is a substantial memorial. Arthur Sullivan, on his way to Paris, witnessed the incident, writing, "I saw it all – saw the unfortunate vessel slowly go over and disappear under the water in clear, bright sunshine, and the water like a calm lake. It was too horrible – and then we saw all the boats moving about picking up the survivors, some so exhausted they had to be lifted on to the ships."[8] Among those rescued was the ship's captain, Count Alexander von Monts.[9]

König Wilhelm was also badly damaged in the collision, with severe flooding forward. König Wilhelm's captain initially planned on beaching the ship to prevent it from sinking, but determined that the ship's pumps could hold the flooding to an acceptable level. The ship made for Portsmouth, where temporary repairs could be effected to allow the ship to return to Germany.[6] In the aftermath of the collision, the German navy held a court martial for Rear Admiral Batsch, the squadron commander, and Captains Monts and Kuehne, the commanders of the two ships, along with Lieutenant Clausa, the first officer aboard Grosser Kurfürst, to investigate the sinking.[10]

Inquiry

In the ensuing inquiry, chaired by Rear Admiral Reinhold von Werner, Monts testified that he had not been given sufficient time to familiarize himself with the ship and its crew, who were themselves unfamiliar with the vessel. Monts argued that the mobilization process for the newly commissioned ship should have lasted four to six weeks, rather than the three he had been given. The day before the squadron left Wilhelmshaven, Batsch complained to General Albrecht von Stosch, the chief of the Kaiserliche Marine, that a significant number of dockyard workers were still finishing work on Grosser Kurfürst. Werner and the board determined that Admiral Batsch was at fault and exonerated Monts.[11]

Stosch was infuriated that the proceedings had been allowed to become a forum for criticism of his policies, for which he blamed Werner. He appealed to Kaiser Wilhelm I, stating that the inquiry had unfairly blamed Admiral Batsch, and requested a new court martial for the involved officers. Simultaneously, Stosch began a campaign to force Werner out of the navy. This was in part to ensure that Batsch, his protégé, would be next in line after Stosch retired.[12] Despite his popularity, particularly with Kaiser Wilhelm I and his son, Werner was unable to resist Stosch's efforts to force his ouster. On 15 October 1878, he requested retirement.[13]

The second court martial again found Batsch guilty and Monts innocent of negligence. A third investigation, held in January 1879, reversed the decision of the previous verdicts and sentenced Monts to a prison term of one month and two days, though the Kaiser refused to implement the punishment. This necessitated another trial, which returned to the initial verdict and sentenced Batsch to six months in prison. The Kaiser commuted Batsch's sentence after he had served two months' time. Disappointed that his protégé had taken the blame for the sinking, Stosch requested another court martial for Monts, who was found not guilty. The Kaiser officially approved the verdict, which put an end to the series of trials over the sinking of Grosser Kurfürst.[14]

Footnotes

Notes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Gröner, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Gröner, p. 6.

- ↑ Gardiner, p. 244.

- ↑ Gröner, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 Sondhaus Weltpolitik, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 Irving, p. 135.

- ↑ Sullivan, in a letter to his mother dated 2 June 1878, quoted in Jacobs, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Sondhaus Weltpolitik, p. 126.

- ↑ The New York Times 1879-01-09.

- ↑ Sondhaus Weltpolitik, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Sondhaus Weltpolitik, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Sondhaus Weltpolitik, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Sondhaus Weltpolitik, pp. 131–132.

References

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-8317-0302-8.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6. OCLC 22101769.

- Irving, Joseph (1879). The Annals of Our Time. London: Macmillan and Co.

- Jacobs, Arthur (1986). Arthur Sullivan – A Victorian Musician. Oxford University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-0-19-282033-4.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21478-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1997). Preparing for Weltpolitik: German Sea Power Before the Tirpitz Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-745-7.

- "Current Foreign Topics. A Court-Martial Ordered in the Case of the Collision of German War Ships". The New York Times. 9 January 1879. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

External links

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 51°0′36″N 1°9′39″E / 51.01000°N 1.16083°E