SMS Brandenburg

Painting of SMS Brandenburg in 1902 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Brandenburg |

| Namesake: | Province of Brandenburg |

| Builder: | AG Vulcan Stettin |

| Laid down: | May 1890 |

| Launched: | 21 September 1891 |

| Commissioned: | 19 November 1893 |

| Fate: | Scrapped in 1920 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Brandenburg-class battleship |

| Displacement: | 10,670 t (10,500 long tons) |

| Length: | 115.7 m (379 ft 7 in) |

| Beam: | 19.5 m (64 ft 0 in) |

| Draft: | 7.9 m (25 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power: | 10,000 ihp (7,500 kW) |

| Propulsion: | 2-shaft triple expansion engines |

| Speed: | 16.9 knots (31.3 km/h; 19.4 mph) |

| Range: | 4,300 nautical miles (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

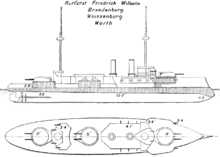

SMS Brandenburg[lower-alpha 1] was the lead ship of the Brandenburg-class pre-dreadnought battleships, which included Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm, Weissenburg, and Wörth built for the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) in the early 1890s. She was the first pre-dreadnought built for the German Navy; earlier, the Navy had only built coastal defense ships and armored frigates.[1] The ship was laid down at the AG Vulcan dockyard in 1890, launched on 21 September 1891, and commissioned into the German Navy on 19 November 1893. Brandenburg and her three sisters were unique for their time in that they carried six heavy guns instead of the four that were standard in other navies. She was named after the Province of Brandenburg.

Brandenburg saw her first major deployment in 1900, when she and her three sister ships were deployed to China to suppress the Boxer Rebellion. Upon returning to Germany, Brandenburg and her sisters, with the exception of Wörth, took part in extensive fleet maneuvers in 1902. In the early 1900s, all four ships were heavily rebuilt. However, she was obsolete by the start of World War I, and only served in a limited capacity, initially as a coastal defense ship, but primarily as a barracks ship. Following the end of the war, Brandenburg was scrapped in Danzig in 1920.

Design

Brandenburg was 115.7 m (379 ft 7 in) long, with a beam of 19.5 m (64 ft 0 in) and a draft of 7.6 m (24 ft 11 in). Brandenburg displaced 10,013 t (9,855 long tons) as designed, and up to 10,670 t (10,501 long tons) at full combat load. She was equipped with two sets of 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion steam engines that produced 10,000 indicated horsepower (7,457 kW) and a top speed of 16.9 knots (31.3 km/h; 19.4 mph) on trials. Steam was provided by twelve transverse cylindrical water-tube boilers. She had a maximum range of 4,300 nautical miles (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Her crew numbered 38 officers and 530 enlisted men.[2]

Brandenburg was armed with a main battery of six 28 cm (11 in) guns of two types. The forward and rear turret guns were 40 calibers long, while the amidships guns were only 35 calibers; this was necessary to allow them to train to either side of the ship. Her secondary armament initially consisted of seven 10.5 cm (4.1 in) guns, though an additional gun was added during the modernization in 1901. She also carried eight 8.8 cm (3.45 in) guns and six 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes. The ship was protected with compound armor. Her main belt armor was 400 millimeters (15.7 in) thick in the central section that protected the ammunition magazines and machinery spaces. The deck was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick. The main battery barbettes were protected with 300 mm (11.8 in) thick armor.[2]

Service history

Brandenburg was ordered as battleship A, the first ship of her class.[2] She was laid down at Germaniawerft in Kiel in 1890. Her hull was completed by September 1891 and launched on 21 September. Fitting out work followed and was finished by later 1893; the ship was commissioned into the fleet on 19 November 1893, less than four weeks after her sister Wörth, the first vessel in the class to join the fleet.[3]

On 16 February 1894, several steam pipes exploded in the ship.[4] The door between the two engine rooms was open, which allowed the steam to enter both of them. Thirty-nine men were killed in the blast and nine were severely injured. Of these, six later died from their injuries.[5] In June 1895, the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal was completed; to celebrate, dozens of warships from 14 different countries gathered in Kiel for a celebration hosted by Kaiser Wilhelm II, including Brandenburg and her three sisters.[6]

Boxer Rebellion

During the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, Chinese nationalists laid siege to the foreign embassies in Peking and murdered Baron Clemens von Ketteler, the German minister.[7] The widespread violence against Westerners in China led to a creation of an alliance between Germany and seven other Great Powers: the United Kingdom, Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary, the United States, France, and Japan.[8] Those soldiers who were in China at the time were too few in number to defeat the Boxers;[9] in Peking there was a force of slightly more than 400 officers and infantry from the armies of the eight European powers.[10] At the time, the primary German military force in China was the East Asia Squadron, which consisted of the protected cruisers Kaiserin Augusta, Hansa, and Hertha, the small cruisers Irene and Gefion, and the gunboats Jaguar and Iltis.[11] Like many other foreign ships, the German squadron was anchored off the Chinese Taku Forts, which guarded access to Peking.[12]

To relieve the foreign legations, British Admiral Edward Seymour mounted a multinational force of 2,100 men that disembarked and marched toward the Chinese capital.[13] That force included a German 500-man detachment dispatched from the fleet anchored off the Taku Forts.[14] Due to heavy resistance, however, the Seymour Expedition could not reach Peking and was forced to retreat toward Tientsin.[15] As a result, the Kaiser determined an expeditionary force would be sent to China to reinforce the East Asia Squadron. Hela was part of the naval expedition, which included the four Brandenburg-class pre-dreadnought battleships, sent to China to reinforce the German flotilla there.[16] Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz opposed the plan, which he saw as unnecessary and costly.[17] The force was sent in spite of von Tirpitz's objections; it arrived in China in September 1900. By that time, the siege of Peking had already been lifted.[18] As a result, the task force suppressed local uprisings around the German concession of Kiaochow. In the end, the operation cost the German government more than 100 million marks. The force returned to Germany the following year, in 1901.[17]

Fleet training, 1902

On 31 August 1902, the annual fleet maneuvers began. The first portion of the exercise positioned Germany in a naval war against a powerful enemy that had superior forces in the North and Baltic Seas. A German squadron, consisting of the coastal defense ships Hagen, Heimdall, and Hildebrand and a division of torpedo boats were trapped in the Kattegat by a superior enemy unit in the North Sea. The "German" squadron was tasked with returning to Kiel in the Baltic, where it would return to Wilhelmshaven via the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal to rejoin the rest of the fleet. Brandenburg, along with Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and Weissenburg and the cruisers Nymphe, Amazone, and Hela, was positioned in one of the three main channels from the Kattegat to Kiel to act as an opposing force. Two other battle squadrons were positioned to block the advance of the isolated "German" squadron.[19]

.jpg)

On the morning of 2 September, the operation commenced.[19] At 06:00 that morning, the commander of the "German" squadron decided to take his ships through the channel to which Brandenburg was assigned.[20] The "hostile" torpedo-boat screen sighted the German flotilla, but a dense fog precluded effective pursuit by the battleships. The fog was so thick that Brandenburg and her two sisters had to drop anchor to avoid any unnecessary risks.[21] Later that evening, the three "opponent" forces rendezvoused to pursue the "German" ships. However, the cruiser and the torpedo boat screen was detached to engage the "German" torpedo-boat screen. The lighter ships quickly "destroyed" several of the "German" torpedo boats. This prompted the "German" squadron to retreat northward with the cruisers in pursuit. The German squadron was chased back through the Kattegat before the exercise was called off. On the night of 3 September, the entire fleet anchored off Læsø island to give the crews a rest.[22]

The following day, 4 September, the exercise resumed. The German squadron was reinforced by several battleships and the armored cruiser Prinz Heinrich. The German flotilla was ordered to sail into the North Sea and attempt to reach the safety of the island fortress of Helgoland. A short engagement between the hostile screen and Prinz Heinrich ensued, during which Prinz Heinrich damaged the protected cruisers Freya and Victoria Louise. A torpedo boat attack on the German squadron followed in the early hours of 5 September.[22] The hostile force was unable to prevent the escape of the German squadron, however, which reached Helgoland by 12:00.[23]

The fleet anchored off Helgoland on 8–11 September. During the day the ships conducted training with steam tactics. On 11 September the ships returned to Wilhelmshaven where on the following two days the ships replenished their coal supplies. On 14 September the final operation of the annual maneuvers began. The situation specified that the naval war had gone badly for Germany; only four battleships, including Brandenburg, Baden, Beowulf, and Württemberg, were still in service. This motley force was augmented by a pair of cruisers and a division of torpedo boats. The ships were to be stationed in the mouth of the Elbe river to protect the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and access to Hamburg.[24] On 15 September, the "hostile" force blockaded the Elbe, along with other rivers and harbors on the North Sea. The hostile battleship squadron steamed to the mouth of the Elbe, where Hela, Freya, and the remaining torpedo boats were stationed as lookouts.[25] Nothing happened during the day of 16 September, but that night several German torpedo boats managed to destroy one of the blockading cruisers and badly damage another.[26] The weather began to storm so the operation was postponed until the following day. That morning, the hostile fleet forced its way into the Elbe, past the fortifications at the mouth of the river. The German flotilla made a desperate attack which resulted in the sinking of two of the hostile battleships. The hostile force, however, ultimately overwhelmed the outnumbered German ships and the exercise ended with their victory.[27]

Reconstruction and later service

In the early 1900s, the four Brandenburgs were taken into the drydocks at the Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven for major reconstruction. Wörth was the first vessel of the class to enter drydock in 1901; Brandenburg didn't follow until 1903.[2] During the modernization, a second conning tower was added in the aft superstructure, along with a gangway.[28] Brandenburg and the other ships had their boilers replaced with newer models, and also had the hamper amidships reduced.[1]

After emerging from the dry dock after modernization, Brandenburg and the other battleships of her class were assigned to the II Battle Squadron of the fleet and replaced the old Siegfried-class coastal defense ships and the armored frigates Baden and Württemberg.[29] The Deutschland-class battleships, which began to enter service in 1906, replaced Brandenburg and her three sister-ships in the battle fleet. Brandenburg and Wörth were put into reserve, joining the Siegfried-class ships.[30] Brandenburg's other sisters, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and Weissenburg, were sold to the Ottoman Empire in 1910.[1]

World War I

At the outbreak of World War I, Brandenburg was brought out from the "moth ball cemetery" and recommissioned into the fleet.[31] She served with her sister Wörth, but due to the age of the ships, this lasted only until 1915. They were then withdrawn from active service. That year, both ships were put into service as barracks ships; Wörth was stationed in Danzig while Brandenburg was placed in Libau.[1] Both Wörth and Brandenburg were struck from the naval register on 13 May 1919 and sold for scrapping.[32] The two ships were purchased by Norddeutsche Tiefbauges, a shipbreaking firm headquartered in Berlin. Wörth was then broken up for scrap in Danzig.[28]

Notes

- ↑ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Hore, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Gröner, p. 13.

- ↑ Gardiner Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 247.

- ↑ Haydn & Vincent, p. 553.

- ↑ Cassier's Magazine, p. 48.

- ↑ Brassey 1896, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Bodin, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Bodin, p. 1.

- ↑ Holborn, p. 311.

- ↑ Bodin, p. 6.

- ↑ Harrington, p. 29.

- ↑ Preston, p. 89.

- ↑ Preston, p. 90.

- ↑ Preston, p. 91.

- ↑ Preston, pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Brassey 1896, p. 74.

- 1 2 Herwig, p. 103.

- ↑ Sondhaus, p. 186.

- 1 2 R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 91.

- ↑ R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 92.

- ↑ R.U.S.I. Journal, pp. 92–93.

- 1 2 R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 93.

- ↑ R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 94.

- ↑ R.U.S.I. Journal, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 95.

- ↑ R.U.S.I. Journal, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 96.

- 1 2 Gröner, p. 14.

- ↑ The United Service, p. 356.

- ↑ Brassey 1907, p. 42.

- ↑ Stumpf, p. 71.

- ↑ Gardiner & Gray, p. 141.

References

- Bodin, Lynn E. (1979). The Boxer Rebellion. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-335-5.

- Brassey, Thomas Allnutt (1896). Brassey's Annual: The Armed Forces Yearbook. New York: Praeger Publishers.

- Brassey, Thomas Allnutt (1907). Brassey's Annual: The Armed Forces Yearbook. New York: Praeger Publishers.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8. OCLC 12119866.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Harrington, Peter (2001). Peking 1900: The Boxer Rebellion. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-181-7.

- Haydn, Joseph; Vincent, Benjamin (1904). Haydn's Dictionary of Dates and Universal Information Relating to All Ages and Nations. G. P. Putnam's sons.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst, New York: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9. OCLC 57239454.

- Holborn, Hajo (1982). A History of Modern Germany: 1840–1945. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00797-7.

- Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

- Preston, Diana (2000). The Boxer Rebellion: The Dramatic Story of China's War on Foreigners That Shook the World in the Summer of 1900. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-18084-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21478-0.

- Stumpf, Richard (1967). Horn, Daniel, ed. War, Mutiny and Revolution in the German Navy: The World War I Diary of Seaman Richard Stumpf. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Weir, Gary E. (1992). Building the Kaiser's Navy: The Imperial Navy Office and German Industry in the Tirpitz Era, 1890–1919. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-929-1. OCLC 22665422.

- "American Naval Engineers: Their Rank and Titles". Cassier's Magazine (New York: Cassier Magazine Company) 10 (1–6). 1896.

- "Our Contemporaries". The United Service (New York: Lewis R. Hamersly & Co). 132–139. 1904.

- "German Naval Manoeuvres". R.U.S.I. Journal (London: Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies) 47: 90–97. 1903.

| ||||||||||||||||||