Rye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother (and heir to the throne) James, Duke of York. Historians vary in their assessment of the degree to which details of the conspiracy were finalised. Whatever the state of the assassination plot, plans to mount a rebellion against the Stuart monarchy were being entertained by some opposition leaders in England, and the government cracked down hard on those in a series of state trials, accompanied with repressive measures and widespread searches for arms. The Plot presaged, and may have hastened, the rebellions of 1685.

Background

After the Restoration of the monarchy under Charles II in 1660 there was concern among some members of Parliament, former republicans and sections of the Protestant population of England that the King's relationship with France under Louis XIV and the other Catholic rulers of Europe was too close. Anti-Catholic sentiment, which associated Roman Catholicism with absolutism, was widespread, and focused particular attention on the succession to the English throne. While Charles was publicly Anglican, he and his brother were known to have Catholic sympathies. These suspicions were confirmed in 1673 when James was discovered to have converted to Roman Catholicism.

In 1681, triggered by the opposition-invented Popish Plot, the Exclusion Bill was introduced in the House of Commons, which would have excluded James from the succession. Charles outmanoeuvred his opponents and dissolved the Oxford Parliament. This left his opponents with no lawful method of preventing James's succession, and rumours of plots and conspiracies abounded. With the "country party" in disarray, Lord Melville, Lord Leven, and Lord Shaftesbury, leader of the opposition to Charles's rule, fled to Holland where Shaftesbury soon died. Many well-known members of Parliament and noblemen of the "country party" would soon be known as Whigs, a faction name that stuck.

The plot

Rye House, located north-east of Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, was a fortified mediaeval mansion surrounded by a moat.[1] The house was leased by a republican and Civil War veteran, Richard Rumbold. The plan was to conceal a force of men in the grounds of the house and ambush the King and the Duke as they passed by on their way back to London from the horse races at Newmarket. The "Rye House plotters", an extremist Whig group who are now named for this plot, allegedly adopted this plan out of a number of possibilities, having decided that it gave tactical advantages and could be carried out with a relatively small force operating with guns from good cover.[2]

The royal party were expected to make the journey on 1 April 1683, but there was a major fire in Newmarket on 22 March, which destroyed half the town. The races were cancelled, and the King and the Duke returned to London early. As a result, the planned attack never took place.

The Rye House and other plotters

The conspirators of this period were numerous, and the resort to some sort of armed resistance was widely debated from the early 1680s, on what was becoming the Whig side of the factional division of British politics. The form it should take was uncertain, and discussions of the seizing of control of cities other than London, such as Bristol, and a Scottish uprising, were in the air. The subsequent historiography of the Plot was largely partisan, and scholars are still clarifying who was closely involved in the planning of violent and revolutionary measures.

The West cabal

The assassination plot centred on a group that was convened in 1682–3 by Robert West of the Middle Temple, a Green Ribbon Club member:[3] it is now often called the Rye House cabal. West had participated in one of the cases that wound up the Popish Plot allegations, that of the false witness Stephen College. Through that association he made contact with Aaron Smith and William Hone, both to be plotters though aside from the main group.[4] John Locke had arranged accommodation for West in Oxford at that time, and had other associations in the group of revolutionary activists (Smith, John Ayloffe, Christopher Battiscombe and Israel Hayes),[5] of whom Ayloffe was certainly implicated in the Rye House Plot, leaving Locke vulnerable.

Rumbold was introduced to West's group by John Wildman; but by the time the plot was discovered both had distanced themselves, Wildman by refusing to finance Rumbold in the purchase of arms, and Rumbold through loss of his earlier enthusiasm.[6][7]

The uprising plans

Cabal members such as Richard Nelthorpe favoured a rebellion rather than an assassination, aligning much of the West group's discussion with the plans of Algernon Sidney, in particular, and the more aristocratic country party members making up the so-called Monmouth cabal.[8] There were discussions in the group around Monmouth in September 1682 of an uprising, having participants in common with the group around West.[9] The "cabal" was later named as the "council of six", which took form after the Tory successes in summer 1682 in the struggle to control the City of London. A significant aspect was the intention to employ Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll for a military rebellion in Scotland.[10] Smith in January 1683 was sent to contact supporters in Scotland, for the "six", with a view to summoning them to London; but apparently botched the mission by indiscretions.[11]

In fact West's contacts with the Monmouth cabal, and knowledge of their intentions, were in part quite indirect Thomas Walcot and Robert Ferguson had accompanied Shaftesbury to the Netherlands, in his self-imposed exile of November 1682. They then both returned to London, and associated with West, who learned from Walcott of Shaftesbury's own plan for a general rebellion. Walcott went on to say that he would lead the attack on the royal guards, but he was another of the plotters who drew the line at assassination.[6] During the spring of 1683 there were further contacts of the Monmouth cabal and West's group, through Sir Thomas Armstrong in particular, about drafting a manifesto, there being disagreements about whether a republican or monarchical constitution should result from revolutionary measures.[9] In May 1683 West and Walcott discussed with a larger group[12] the prospects for raising a force of several thousand men, around London.[13]

Scottish and American connections

The interpretation of actual Whig intentions at this time is complicated by colonial schemes in America. West had a stake in East Jersey.[3] Shaftesbury was heavily involved in the Province of Carolina. In April 1683 some Scottish contacts of the Whigs arrived in London, as briefed by Smith, meeting Essex and Russell of the Monmouth cabal; they were either under the impression that the matter concerned Carolina,[14] or gave this out as a pretext for their presence.[15] They included Sir George Campbell of Cessnock, John Cochrane, and William Carstares.[16] The Earl of Argyll had left London for the Netherlands in August 1682, but kept in touch with Whig notables through couriers and ciphered correspondence. Two of them, William Spence alias Butler, and Abraham Holmes, were arrested in June 1683.[17][18]

Informers and arrests

News of the plot leaked when Josiah Keeling gave information on it to Sir Leoline Jenkins;[19] and the plot was publicly discovered 12 June 1683. Keeling had contacted a courtier, who put him in touch with George Legge, 1st Baron Dartmouth, and Dartmouth had brought him to Jenkins, Secretary of State.[20] Keeling's testimony was used at the trials of Walcott, Hone, Sidney, and Charles Bateman; and it earned him a pardon.[19] It also started a lengthy process of incriminated persons confessing, in the hope of clemency. Using his brother, Keeling was able to get further direct evidence of conspiracy, and Jenkins brought in Rumsey and West, who told him what they knew, from 23 June;[21] West had volunteered information via Laurence Hyde, 1st Earl of Rochester, on the 22nd. Over several days West explained the Rye House plot and his part in purchasing arms, supposed to be for America. He did little to incriminate the Monmouth group; his testimony was later used against Walcott and Sidney. West received a pardon in December 1684.[3]

Thomas Walcott was arrested on 8 July, and was the first conspirator to go to trial. A meeting of the plotters had been held at his house on 18 June; but rather than escape, he chose to write to Jenkins, with the offer of a full confession in return for a pardon.[8] Among the plotters, John Row from Bristol was considered particularly unreliable, and he had a direct connection to the Monmouth household to offer as information; a number of steps were taken to silence him, and his life was under threat more than once.[22] After the meeting Nelthorpe and Edward Norton called on William Russell, Lord Russell, with an appeal to take up arms immediately; when Russell was unwilling, Nelthorpe left the country.[23]

Walcott named Henry Care, publisher of the Weekly Pacquet which was a leading anti-Catholic and Whig paper of the time; Care ceased publishing the Pacquet on 13 July, and began co-operating with the court.[24] Among those later informing against Walcott was Zachary Bourne.[8] Bourne was a conspirator, arrested trying to leave the country with the nonconformist ministers Matthew Meade, for whom an arrest warrant was issued on 27 June, and Walter Cross;[25] he informed against another minister, Stephen Lobb, who was prepared to help recruiting for an uprising. On 6 July the arrest of Lobb was ordered, and he was picked up in August.[26]

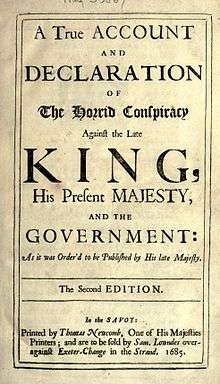

A royal declaration of the heinous nature of the plot was issued on 27 July.[27] Many more were arrested. Although the principal conspirators were minor figures, and not directly concerned in the "Monmouth cabal", the court party made no distinction between the groups. The ministers involved may have known Ferguson but not West; Meade had sheltered the Covenanter John Nisbet, and may well have known of the plans for a rebellion.[25] William Carstares, a Church of Scotland minister and intermediary with the Whig grandees, was found in Kent on 23 July.[28]

Trials

Executed

- Sir Thomas Armstrong, Member of Parliament for Stafford – Hanged, drawn and quartered

- John Ayloffe – Hanged, drawn and quartered

- Henry Cornish, Sheriff of the City of London – Hanged, drawn and quartered

- Elizabeth Gaunt – Burnt at the stake

- James Holloway – Hanged, drawn and quartered

- Baillie of Jerviswood – Hanged.

- Richard Nelthorpe – Hanged

- Richard Rumbold – Hanged, drawn and quartered

- William Russell, Lord Russell, Member of Parliament for Bedfordshire – Executed by beheading.

- Algernon Sidney, former Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports – Executed by beheading.

- Thomas Walcot – Hanged, drawn and quartered

- John Rouse - Hanged, drawn and quartered

Sentenced to death but later pardoned

Imprisoned

- Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll – Later beheaded for the Monmouth Rebellion

- Sir Samuel Barnardiston, 1st Baronet – Also fined £6,000.

- Henry Booth, 1st Earl of Warrington

- Paul Foley, Member of Parliament for Hereford

- Thomas Grey, 2nd Earl of Stamford

- John Hampden, Member of Parliament for Wendover – Also fined £40,000

- William Howard, 3rd Baron Howard of Escrick, was arrested and turned informer at the trial of William Russell, Lord Russell (July 1683). He gave accounts of meetings at John Hampden's and Russell's houses, which mainly led to Russell's conviction. His evidence similarly ruined Sidney.

- Matthew Mead

- Aaron Smith

- Sir John Trenchard, Member of Parliament for Taunton

- Sir John Wildman

Exiled/fled

- Sir John Cochrane – Fled to Holland

- Robert Ferguson – Fled to the Netherlands

- Ford Grey, 3rd Baron Grey of Werke – Escaped from the Tower

- Patrick Hume, 1st Earl of Marchmont – Fled to the Netherlands

- John Locke – Fled to the Netherlands

- John Lovelace, 3rd Baron Lovelace – Fled to Holland

- David Melville, 3rd Earl of Leven – Fled to the Netherlands

- George Melville, 1st Earl of Melville – Fled to the Netherlands

- Edward Norton – Fled to Holland

- Nathaniel Wade – Fled to Holland

Committed suicide

- Arthur Capell, 1st Earl of Essex – Cut his own throat in the Tower of London.

Tortured

Implicated

- James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount of Stair

- Edward Hungerford, Member of Parliament for Chippenham

- James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, Charles' illegitimate son, was obliged to retire to the United Provinces – Later beheaded for the Monmouth Rebellion

- John Owen

The final trial on the Rye House charges was that of Charles Bateman, in 1685. Witnesses against him were the conspirators Keeling, who had nothing specific to say, Thomas Lee, and Richard Goodenough. He was hanged, drawn and quartered.[29]

Having fled abroad the previous year, Sir William Waller moved to Bremen in 1683. While he was there he became a central figure in a group of the erstwhile conspirators who were in political exile. Lord Preston, the English ambassador at Paris, called him "the governor" and wrote that "They style Waller, by way of commendation, a second Cromwell". Waller would accompany William of Orange to England in 1688 but William chose to overlook him when his government was formed.[30]

Evaluations

Historians have suggested the story of the plot may have been largely manufactured by Charles or his supporters to allow the removal of most of his strongest political opponents. Richard Greaves cites as proof that there was a plot in 1683, the 1685 armed rebellions of the fugitive Earl of Argyll and Charles' Protestant illegitimate son, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth (Greaves 1992). Doreen Milne[31] asserts that its importance lies less in what was actually plotted than in the public perception of it and the uses made of it by the government.

Popular reaction to the Tories' reactive excesses, sometimes known as the "Stuart Revenge" though that term is contested, led to the discontent expressed decisively in the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

Notes

- ↑ Thompson 1987:87

- ↑ Alan Marshall, Intelligence and Espionage in the Reign of Charles II, 1660–1685 (2003), p. 291; Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Zook, Melinda. "West, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39674. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ De Krey, Gary S. "College, Stephen". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5906. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Richard Ashcraft, Revolutionary Politics and Locke's Two Treatises of Government (1986), p. 376; Google Books.

- 1 2 Greaves, Richard L. "Wildman, Sir John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29405. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Clifton, Robin. "Rumbold, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 Greaves, Richard L. "Walcott, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/67375. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 Greaves, Richard L. "Armstrong, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/665. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ The "council of six" comprised Monmouth, Sidney, Lord Russell, the Earl of Essex, Howard of Escrick, and John Hampden. Cambridge Modern History: The Renaissance (1907), p. 229; Google Books.

- ↑ Hopkins, Paul. "Smith, Aaron". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25765. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Including Francis Goodenough, Richard Goodenough, James Holloway, Edward Norton, John Rumsey, and Nathaniel Wade.

- ↑ Greaves, Richard L. "Holloway, James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13574. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ George Wingrove Cooke, The History of Party: from the rise of the Whig and Tory factions, in the reign of Charles II, to the passing of the Reform Bill vol. 1 (1836), p. 260; Google Books.

- ↑ Greaves, Richard L. "Campbell, Sir George, of Cessnock". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/67392. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Ashcraft, p. 354; Google Books.

- ↑ Harris, Tim. "Spence, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/67376. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Zook, Melinda. "Holmes, Abraham". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13588. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 De Krey, Gary S. "Keeling, Josiah". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15242. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑

"Keeling, Josiah". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Keeling, Josiah". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - ↑

"Russell, William (1639–1683)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Russell, William (1639–1683)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - ↑ Greaves, Richard L. "Row, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/67384. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Greaves, Richard L. "Nelthorpe, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19891. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Lois G. Schwoerer, The Ingenious Mr. Henry Care, Restoration Publicist (2001), p. 226.

- 1 2 Greaves, Richard L. "Meade, Matthew". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18466. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Greaves, Richard L. "Lobb, Stephen". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16878. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Milne 1951:95

- ↑ Clarke, Tristram. "Carstares, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4777. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Leonard A. Parry, Willard H. Wright, Some Famous Medical Trials (2000), pp. 211–2; Google Books.

- ↑ Firth 1899, p. 135 cites: Hist. MSS. Comm. 7th Rep. pp. 296, 311, 347, 386.

- ↑ Milne 1951

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rye House Plot. |

- Greaves, Richard L. Secrets of the Kingdom: British Radicals from the Popish Plot to the Revolution of 1688–89 (Stanford University Press) 1992.

Firth, Charles Harding (1899). "Waller, William (d.1699)". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 59. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 135.

Firth, Charles Harding (1899). "Waller, William (d.1699)". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 59. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 135. - Milne, Doreen J. "The Results of the Rye House Plot and Their Influence upon the Revolution of 1688: The Alexander Prize Essay" Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 5th Seris, 1 (1951), p. 91–108.

- Thompson, Michael Welman The Decline of the Castle (Cambridge University Press) 1987