Ancient Egyptian multiplication

In mathematics, ancient Egyptian multiplication (also known as Egyptian multiplication, Ethiopian multiplication, Russian multiplication, or peasant multiplication), one of two multiplication methods used by scribes, was a systematic method for multiplying two numbers that does not require the multiplication table, only the ability to multiply and divide by 2, and to add. It decomposes one of the multiplicands (generally the larger) into a sum of powers of two and creates a table of doublings of the second multiplicand. This method may be called mediation and duplation, where mediation means halving one number and duplation means doubling the other number. It is still used in some areas.

The second Egyptian multiplication and division technique was known from the hieratic Moscow and Rhind Mathematical Papyri written in the seventeenth century B.C. by the scribe Ahmes.

Although in ancient Egypt the concept of base 2 did not exist, the algorithm is essentially the same algorithm as long multiplication after the multiplier and multiplicand are converted to binary. The method as interpreted by conversion to binary is therefore still in wide use today as implemented by binary multiplier circuits in modern computer processors.

The decomposition

The ancient Egyptians had laid out tables of a great number of powers of two, rather than recalculating them each time. The decomposition of a number thus consists of finding the powers of two which make it up. The Egyptians knew empirically that a given power of two would only appear once in a number. For the decomposition, they proceeded methodically; they would initially find the largest power of two less than or equal to the number in question, subtract it out and repeat until nothing remained. (The Egyptians did not make use of the number zero in mathematics.)

To find the largest power of 2 keep doubling your answer starting with number 1, for example

1 × 2 = 2 2 × 2 = 4 4 × 2 = 8 8 × 2 = 16 16 × 2 = 32

Example of the decomposition of the number 25:

The largest power of two less than or equal to 25 is 16: 25 – 16 = 9 The largest power of two less than or equal to 9 is 8: 9 – 8 = 1 The largest power of two less than or equal to 1 is 1: 1 – 1 = 0 25 is thus the sum of the powers of two: 16, 8 and 1.

The table

After the decomposition of the first multiplicand, it is necessary to construct a table of powers of two times the second multiplicand (generally the smaller) from one up to the largest power of two found during the decomposition. In the table, a line is obtained by multiplying the preceding line by two.

For example, if the largest power of two found during the decomposition is 16, and the second multiplicand is 7, the table is created as follows:

| 1 | 7 |

| 2 | 14 |

| 4 | 28 |

| 8 | 56 |

| 16 | 112 |

The result

The result is obtained by adding the numbers from the second column for which the corresponding power of two makes up part of the decomposition of the first multiplicand.

The main advantage of this technique is that it makes use of only addition, subtraction, and multiplication by two.

Example

Here, in actual figures, is how 238 is multiplied by 13. The lines are multiplied by two, from one to the next. A check mark is placed by the powers of two in the decomposition of 238.

| 1 | | ||||||

| ✓ | 2 | 26 | |||||

| ✓ | 4 | 52 | |||||

| ✓ | 8 | 104 | |||||

| 16 | | ||||||

| ✓ | 32 | 416 | |||||

| ✓ | 64 | 832 | |||||

| ✓ | 128 | 1664 | |||||

| | |||||||

| 238 | 3094 | ||||||

Since 238 = 2 + 4 + 8 + 32 + 64 + 128, distribution of multiplication over addition gives:

| 238 × 13 | = (128 + 64 + 32 + 8 + 4 + 2) × 13 |

| = 128 × 13 + 64 × 13 + 32 × 13 + 8 × 13 + 4 × 13 + 2 × 13 | |

| = 1664 + 832 + 416 + 104 + 52 + 26 | |

| = 3094 |

Russian peasant multiplication

In the Russian peasant method, the powers of two in the decomposition of the multiplicand are found by writing it on the left and progressively halving the left column, discarding any remainder, until the value is 1 (or -1, in which case the eventual sum is negated), while doubling the right column as before. Lines with even numbers on the left column are struck out, and the remaining numbers on the right are added together.[1]

| For example, to multiply 238 by 13, the smaller of the numbers (to reduce the number of steps), 13, is written on the left and the larger on the right. The left number is progressively halved (discarding any remainder) and the right one doubled, until the left number is 1: | ||||

| 13 | 238 | |||

| 6 | (remainder discarded) | 476 | ||

| 3 | 952 | |||

| 1 | (remainder discarded) | 1904 | ||

| Lines with even numbers on the left column are struck out, and the remaining numbers on the right are added, giving the answer as 3094: | ||||

| 13 | 238 | |||

| | | |||

| 3 | 952 | |||

| 1 | + 1904 | |||

| | ||||

| 3094 | ||||

| The algorithm can be illustrated with the binary representation of the numbers: | ||||

| 1101 | (13) | 11101110 | (238) | |

| | | | | |

| 11 | (3) | 1110111000 | (952) | |

| 1 | (1) | 11101110000 | (1904) | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | (238) | |||||

| × | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | (13) | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | (238) | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (0) | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (952) | |||

| + | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (1904) | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | (3094) | |

Background information

Since the 1880s, as formalized in the 1920s, an incomplete view has defined Egyptian multiplication. Springer's on-line encyclopedia summarizes the 1920s view:[2]

The art of computation arose and developed long before the times of the oldest written records extant. The oldest mathematical records are the Cahoon papyri and the famous Rhind papyrus, which is believed to date back to about 2000 B.C. Additive hieroglyphic methods representation numbers (cf. Numbers, representations of) in ways that Old Kingdom Egyptians had performed addition and subtraction operations on natural numbers in relatively simple ways. For example, one multiplication method was carried out by doubling, i.e. the factors were decomposed into sums of powers of two, the individual summands were multiplied, and the components added. Operations on fractions (cf. Fraction) were reduced in Ancient Egypt to operations on aliquot fractions, i.e. on fractions of the type. More complicated fractions were decomposed with the aid of tables into a sum of aliquot fractions.

The 1920s conclusions properly decoded an incomplete additive version of Egyptian multiplication. The 1920s historians had not followed up an 1895 report that suggested a second form of multiplication method was present in Ahmes' RMP 2/n table and RMP 36. The second method included aliquot parts, as Springer suggested. Aliquot part were reported by F. Hultsch in 1895. Hultsch parsed Ahmes' 2/n table revealing aliquot part patterns. Yet, Springer's Egyptian multiplication encyclopedia entry did not specify critical aliquot part operational details that are required to translate the information into modern arithmetic statements. Sadly, 1920s math historians had skipped over several operational details, such as of F. Hultsch's 1895 aliquot part discussion points, thereby improperly concluding that aliquot part patterns had not been seen in Ahmes' 2/n table.

The aliquot part story line remained an unsolved issue until the 21st century. Shortly after 2002 the Kahun Papyrus and the RMP 2/n table revealed two aliquot part operational methods: (1) new inverse multiplication and division methods, and (2) a LCM number method written in red (RMP 38). The multiplication and division methods had been hidden Hultsch's aliquot part operational steps, including red auxiliary numbers steps that selected 'optimized' divisors of the LCM. In 2006, the 1895 Hultsch-Bruins method was confirmed from a second direction, detailing a common aliquot method used in the RMP and Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll. This method scaled the conversion of 1/p, 1/pq, 2/p, 2/pq, n/p and n/pq rational numbers by an LCM m, written as m/m.

Ahmes' aliquot part division steps, sensed in the 19th century, not decoded during the 20th century began to release its secrets after 2001, increasingly by 2006 and 2009 (by RMP 36). Two reasons had misdirected 1920s math historians. The first prematurely closed the subject of Egyptian fraction arithmetic operations by concluding Egyptian multiplication contained only additive steps. Second, scribal division was suggested have followed a non-inverse process called 'single false position'.

Moreover, Springer followed the traditional 1920s definition of Egyptian division by suggesting: "Division was carried out by subtracting from the number to be divided the numbers obtained by successive doubling of the divisor." Math historians call the 1920s proposed Egyptian division method 'single false position'. Ironically, 'single false position' was first documented in 800 AD. Later Arab texts improved its root finding 'double false position' method.

Springer's definition of Egyptian division was historically incomplete. To complete a definition of Egyptian division the first six RMP problems, a division by 10 labor rate (defined earlier in the Reisner Papyrus) set of problems are consulted. In addition, RMP algebra problems and methods are consulted. For example, Ahmes divided 28 by 97, in RMP 31 (confirmed in RMP 34) by solving: x + (2/3 + 1/2 + 1/7) x = 33 and x + (2/3 + 1/2 + 1/7) x = 37 as other vulgar fraction problems were solved in the Kahun Papyrus and Rhind Papyrus 2/n tables. Aliquot part steps were hidden in theoretical multiplication and division operations for over 100 years.

Ahmes did not mention 'single false position' in algebra problems, a valid point made by Robins-Shute in 1987. The inaccurate 1920s supposition has been replaced by parsing large vulgar fractions by stripping away the unit fraction notation. For example, 28/97, in RMP 31, and RMP 23 expose Ahmes' LCM multplication method. In RMP 23 where a 45 multiplier was introduced to solve most of the problem. Yet, to read the complete problem LCM 360 was needed as other RMP algebra problems were solved.

In the 21st century, Ahmes is becoming clearly reported by converting vulgar fractions into optimized unit fractions series within a LCM method. The LCM method also applied aliquot parts of the denominator to solve 2/97 in RMP 31, and in 2/n table. Ahmes converted 28/97 into two problems, 2/97 and 26/97, selecting two LCM multipliers such that:

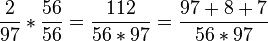

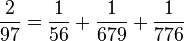

- To convert 2 by 97: Ahmes' 2/n table wrote 2/n conversions less than 2/101, he selected a highly divisible number m as an optimizing multiplier m/m. In the 2/97 case 56 was selected, creating a multiplier 56/56 such that the aliquot parts of 56 (28, 14, 8, 7, 4, 2, 1) were introduced into the solution by writing:

and,

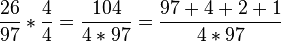

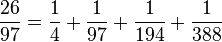

- To convert 26/97 to a unit fraction series Ahmes looked for a multiplier m/m that would increase the numerator to greater than 97. Ahmes found 4/4. By considering the aliquot parts of 4 (4, 2, 1) Ahmes wrote out:

such that:

and,

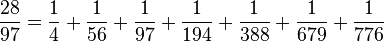

- Ahmes combined steps 2/97 and 26/97 into one Egyptian fraction series by writing:

as RMP 36 converted 30/53 by 2/53 + 28/53 with 2/53 scaled by (30/30) and 28/53 scaled by (2/2).

- Egyptian multiplication was an inverse operation to the Egyptian division operation, and vice versa. The modern looking multiplication and division operations had been hidden within the Egyptian fraction notation.

One implication is that 'single false position' represented a 20th-century supposition that failed to historically read Ahmes' additive numerators written in multiplication problems. Ahmes division operations, described by aliquot part steps in over 20 algebra problems, embed ancient and modern division methods, as inverse to Egyptian multiplications. Egyptian scribes applied several modern theoretical ideas, mostly arithmetic ones, as recorded in Ahmes math tool box.

A second implication is contained in RMP 38. It details Ahmes multiplying 320 ro, one hekat, by 35/11 times 1/10 = 7/22, obtaining 101 + 9/11. Ahmes proved that 101 + 9/11 was correct by multiplying by the inverse of 7/22, or 22/7. Egyptian division generally applied an inverse of Egyptian multiplication in the 1900 BCE Akhmim Wooden Tablet (AWT) and all other Middle Kingdom mathematical texts. The AWT, for example. divided one hekat, (64/64), by n = 3, 7, 10, 11 and 13. Quotient and remainder answers were multiplied by divisor inverses, 1/3, 1/7, 1/10, 1/11 and 1/13, exactly returning the beginning rational number (64/64).

Finally, the red numerator numerators implied by the 2/n table were directly discussed in RMP 36. Ahmes converted, 2/53, 3/53, 5/53, 15/53, 28/53 and 30/53 by two rules. The first rule scaled 2/53*(30/30) = 60/1590, 3/53(20/20) = 60/1060, 5/53*(12/12) = 60/636, 15/53*(4/4) = 60/212, 28/53*(2/2) = 56/106. The second rule converted 30/53 by parsing 30/53 into 2/53 + 28/53. as Ahmes has converted 28/97 by parsing 29/97 into 2/97 + 26/97.

Conclusion: To understand ancient Egyptian multiplication and division, Ahmes' 2/n table aliquot part arithmetic operational steps must be translated into modern arithmetic statements. Ahmes multiplication and division methods were inverse to each other, with RMP 38, and the AWT provided vivid examples of the arithmetic relationships. RMP 36 the details of two rational number conversion methods were detailed, one for n/p, n/pq, 2/p and 2/pq and another for hard to convert n/p rational numbers that were parsed into solvable 2/p and (n-2)/p statements.

Egyptian multiplication contained two aspects, a theoretical side, and a practical side. Egyptian division by a rational number was Egyptian multiplication by an inverse of the rational number. Early Egyptian scholars had not considered the theoretical aspects of the RMP and other Egyptian texts until the 21st century. Theoretical definitions had been hidden in conversion of rational numbers by scaled multipliers applied in an aliquot part rule. RMP 38 multiplied a hekat, stated as 320 ro, by 7/22, and returned 320 ro by multiplying the answer by 22/7. Egyptian division was quotient and remainder based, theoretical aspects that scholars are increasingly studying in terms of aliquot parts, 2/n tables, and other ancient scribal applications after 2005.

See also

- Egyptian mathematics

- Multiplication algorithms

- Binary numeral system

- Bharati Krishna Tirtha's Vedic mathematics

References

- ↑ Cut the Knot - Peasant Multiplication

- ↑ Gardner, Milo. "Egyptian multiplication and division". PlanetMath.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

Other sources

- Boyer, Carl B. (1968) A History of Mathematics. New York: John Wiley.

- Brown, Kevin S. (1995) The Akhmin Papyrus 1995 --- Egyptian Unit Fractions.

- Bruckheimer, Maxim, and Y. Salomon (1977) "Some Comments on R. J. Gillings' Analysis of the 2/n Table in the Rhind Papyrus," Historia Mathematica 4: 445-52.

- Bruins, Evert M. (1953) Fontes matheseos: hoofdpunten van het prae-Griekse en Griekse wiskundig denken. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- ------- (1957) "Platon et la table égyptienne 2/n," Janus 46: 253-63.

- Bruins, Evert M (1981) "Egyptian Arithmetic," Janus 68: 33-52.

- ------- (1981) "Reducible and Trivial Decompositions Concerning Egyptian Arithmetics," Janus 68: 281-97.

- Burton, David M. (2003) History of Mathematics: An Introduction. Boston Wm. C. Brown.

- Chace, Arnold Buffum, et al. (1927) The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. Oberlin: Mathematical Association of America.

- Cooke, Roger (1997) The History of Mathematics. A Brief Course. New York, John Wiley & Sons.

- Couchoud, Sylvia. “Mathématiques égyptiennes”. Recherches sur les connaissances mathématiques de l’Egypte pharaonique., Paris, Le Léopard d’Or, 1993.

- Daressy, Georges. “Akhmim Wood Tablets”, Le Caire Imprimerie de l’Institut Francais d’Archeologie Orientale, 1901, 95–96.

- Eves, Howard (1961) An Introduction to the History of Mathematics. New York, Holt, Rinehard & Winston.

- Fowler, David H. (1999) The mathematics of Plato's Academy: a new reconstruction. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Gardiner, Alan H. (1957) Egyptian Grammar being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs. Oxford University Press.

- Gardner, Milo (2002) "The Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll, Attested Short Term and Long Term" in History of the Mathematical Sciences, Ivor Grattan-Guinness, B.C. Yadav (eds), New Delhi, Hindustan Book Agency:119-34.

- -------- "Mathematical Roll of Egypt" in Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer, Nov. 2005.

- Gillings, Richard J. (1962) "The Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll," Australian Journal of Science 24: 339-44. Reprinted in his (1972) Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs. MIT Press. Reprinted by Dover Publications, 1982.

- -------- (1974) "The Recto of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus: How Did the Ancient Egyptian Scribe Prepare It?" Archive for History of Exact Sciences 12: 291-98.

- -------- (1979) "The Recto of the RMP and the EMLR," Historia Mathematica, Toronto 6 (1979), 442-447.

- -------- (1981) "The Egyptian Mathematical Leather Role–Line 8. How Did the Scribe Do it?" Historia Mathematica: 456-57.

- Glanville, S.R.K. "The Mathematical Leather Roll in the British Museum” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 13, London (1927): 232–8

- Griffith, Francis Llewelyn. The Petrie Papyri. Hieratic Papyri from Kahun and Gurob (Principally of the Middle Kingdom), Vols. 1, 2. Bernard Quaritch, London, 1898.

- Gunn, Battiscombe George. Review of The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus by T. E. Peet. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 12 London, (1926): 123–137.

- Hultsch, F, Die Elemente der Aegyptischen Theihungsrechmun 8, Ubersich uber die Lehre von den Zerlegangen, (1895):167-71.

- Imhausen, Annette. “Egyptian Mathematical Texts and their Contexts”, Science in Context 16, Cambridge (UK), (2003): 367-389.

- Joseph, George Gheverghese. The Crest of the Peacock/the non-European Roots of Mathematics, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2000

- Klee, Victor, and Wagon, Stan. Old and New Unsolved Problems in Plane Geometry and Number Theory, Mathematical Association of America, 1991.

- Knorr, Wilbur R. “Techniques of Fractions in Ancient Egypt and Greece”. Historia Mathematica 9 Berlin, (1982): 133–171.

- Legon, John A.R. “A Kahun Mathematical Fragment”. Discussions in Egyptology, 24 Oxford, (1992).

- Lüneburg, H. (1993) "Zerlgung von Bruchen in Stammbruche" Leonardi Pisani Liber Abbaci oder Lesevergnügen eines Mathematikers, Wissenschaftsverlag, Mannheim: 81=85.

- Neugebauer, Otto (1969) [1957]. The Exact Sciences in Antiquity (2 ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-22332-2.

- Robins, Gay. and Charles Shute, The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus: an Ancient Egyptian Text" London, British Museum Press, 1987.

- Roero, C. S. “Egyptian mathematics” Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences” I. Grattan-Guinness (ed), London, (1994): 30–45.

- Sarton, George. Introduction to the History of Science, Vol I, New York, Williams & Son, 1927

- Scott, A. and Hall, H.R., “Laboratory Notes: Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll of the Seventeenth Century BC”, British Museum Quarterly, Vol 2, London, (1927): 56.

- Sylvester, J. J. “On a Point in the Theory of Vulgar Fractions”: American Journal Of Mathematics, 3 Baltimore (1880): 332–335, 388–389.

- Vogel, Kurt. “Erweitert die Lederolle unserer Kenntniss ägyptischer Mathematik Archiv für Geschichte der Mathematik, V 2, Julius Schuster, Berlin (1929): 386-407

- van der Waerden, Bartel Leendert. Science Awakening, New York, 1963

- Hana Vymazalova, The Wooden Tablets from Cairo:The Use of the Grain Unit HK3T in Ancient Egypt, Archiv Orientalai, Charles U Prague, 2002.

External links

- http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/RMP36AndThe2nTable.html RMP 36 and the 2/n table

- http://rmprectotable.blogspot.com/ RMP 2/n table

- http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/EgyptianMath3.html

- http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2007/844/heritage.htm

- http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/EgyptianMathematicalLeatherRoll2.html

- http://emlr.blogspot.com Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll

- http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/FirstLCMMethodRedAuxiliaryNumbers.html

- http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/AhmesBirdFeedingRateMethod.html Theoretical (expected) economic control numbers, RMP 83

- http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/RationalNumbers.html

- http://mathforum.org/kb/message.jspa?messageID=6579539&tstart=0 Math forum and two ways to calculate 2/7

- New and Old classifications of Ahmes Papyrus

- Russian Peasant Multiplication

- The Russian Peasant Algorithm (pdf file)

- Peasant Multiplication from cut-the-knot

- Egyptian Multiplication by Ken Caviness, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Russian Peasant Multiplication at The Daily WTF

- Michael S. Schneider explains how the Ancient Egyptians (and Chinese) and modern computers multiply and divide

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||