Rushmore (film)

| Rushmore | |

|---|---|

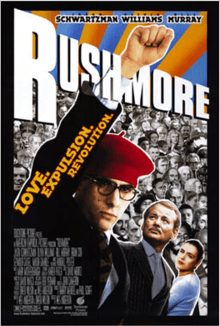

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Wes Anderson |

| Produced by |

Barry Mendel Paul Schiff |

| Written by |

Wes Anderson Owen Wilson |

| Starring |

Jason Schwartzman Bill Murray Olivia Williams Seymour Cassel Brian Cox Mason Gamble Sara Tanaka Stephen McCole Connie Nielsen Luke Wilson |

| Music by | Mark Mothersbaugh |

| Cinematography | Robert Yeoman |

| Edited by | David Moritz |

Production company |

Touchstone Pictures American Empirical Pictures |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $9 million |

| Box office | $17.2 million[1][2] |

Rushmore is a 1998 comedy-drama film directed by Wes Anderson about an eccentric teenager named Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman in his film debut), his friendship with rich industrialist Herman Blume (Bill Murray), and their mutual love for elementary school teacher Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams). The film was co-written by Anderson and Owen Wilson. The soundtrack was scored by regular Anderson collaborator Mark Mothersbaugh and features several songs by bands associated with the British Invasion of the 1960s.

The movie helped launch the careers of Anderson and Schwartzman, while establishing a "second career" for Murray as a respected actor of independent cinema. Rushmore also won Best Director and Best Supporting Male awards at the 1999 Independent Spirit Awards while Murray earned a nomination for Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture.

Empire also named Rushmore the 175th greatest film of all time in 2008. Four years after, Slant Magazine ranked the film #22 on its list of the 100 Best Films of the 1990s.[3] According to ShortList, it is one of the 30 coolest films ever.[4]

Plot

Max Fischer, a mature and eccentric 15-year-old, is a scholarship student at Rushmore Academy, a private school in Houston. He is both Rushmore's most extracurricular and least scholarly student. He spends nearly all of his time on elaborate extracurricular activities, caring little how it affects his grades. He also feuds with the school's headmaster, Dr. Guggenheim.

Herman Blume is a cynical industrialist who finds his operation of a multimillion-dollar company to be unsatisfying. He is frustrated that his marriage is failing and the two sons he's putting through Rushmore are boorish and unrepentant brats spoiled by their mother. Herman comes to admire Max, and the two become close friends. Max admires Herman's success while Herman is impressed by Max's cocksure attitude.

Rosemary Cross is a widowed teacher who arrives at Rushmore as a new first grade instructor. She joined Rushmore after the death of her husband, who was also a former Rushmore student. Max quickly develops an infatuation with Rosemary and makes many attempts at courting her. While she initially tolerates Max, Rosemary becomes increasingly alarmed at his obvious obsession with her. Along the way, Blume attempts to convince Max that Rosemary is not worth the trouble, only to fall for Rosemary himself. The two begin dating without Max's knowledge.

After Max attempts to break ground on an aquarium without the school's approval, he is expelled from Rushmore. He is then forced to enroll in his first public school, Grover Cleveland High. Attempts to engage in outside activities at his new school have mixed results. A fellow student, Margaret Yang, tries to engage Max, but he pays little attention to her. Rosemary and Blume attempt to support him in his new school.

Eventually, Max's friend Dirk discovers the relationship between Rosemary and Blume and informs Max as payback for a rumor Max started about his mother. Max and Blume go from being friends to mortal enemies, and they engage in back-and-forth acts of revenge. Max informs Blume's wife of her husband's affair, thus ending their marriage. Max then puts bees in Blume's hotel room, then Blume destroys Max's bicycle with his car. Max cuts the brake lines on Blume's car, for which he is arrested.

Max eventually gives up and explains to Blume that revenge no longer matters because even if he (Max) wins, Rosemary still would love Blume. Max becomes depressed and stops attending school. He cuts himself off from the world and works as an apprentice at his father's barber shop. One day, Dirk stops by the shop to apologize to Max and bring him a Christmas present. Dirk suggests Max see his old headmaster in the hospital, knowing Blume will be there. Max and Blume meet and are cordial, and Max finds out that Rosemary broke up with Blume. Max begins to apply himself in school again, and he also develops a friendship with Margaret, whom he casts in one of his plays.

Max takes his final shot at Rosemary by pretending to be injured in a car accident, soliciting her affection. When she discovers that Max's injuries are fake, he is rebuffed again. Max makes it his new mission to win Rosemary back for Blume. His first attempt is unsuccessful, but then he invites both Herman and Rosemary to the performance of a play he wrote, making sure they will be sitting together. In the end, she and Blume appear to reconcile. Max and Margaret also become a couple.

Cast

- Jason Schwartzman as Max Fischer

- Bill Murray as Herman Blume

- Olivia Williams as Rosemary Cross

- Seymour Cassel as Bert Fischer

- Brian Cox as Dr. Nelson Guggenheim

- Mason Gamble as Dirk Calloway

- Sara Tanaka as Margaret Yang

- Connie Nielsen as Mrs. Calloway

- Luke Wilson as Dr. Peter Flynn

- Stephen McCole as Magnus Buchan

- Kumar Pallana as Mr. Littlejeans

- Alexis Bledel as Student

Production

With Rushmore, Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson wanted to create their own "slightly heightened reality, like a Roald Dahl children's book".[5] Like Max Fischer, Wilson was expelled from his prep school, St. Mark's School of Texas, in the tenth grade,[5] while Anderson shared Max's ambition, lack of academic ability, and had a crush on an older woman.[6] Anderson and Wilson began writing the screenplay for Rushmore years before they made Bottle Rocket.[5] They knew that they wanted to make a film set in an elite prep school, much like St. Mark's, which Owen had attended along with his two brothers, Andrew and Luke (Luke being the sole graduate), and St. John's School in Houston, Texas which Anderson had attended. The film also featured M. B. Lamar High School. According to the director, "One of the things that was most appealing to us was the initial idea of a 15-year-old kid and a 50-year-old man becoming friends and equals".[7] Rushmore was originally going to be made for New Line Cinema[8] but when they could not agree on a budget, Anderson, Wilson and producer Barry Mendel held an auction for the film rights in mid-1997 and struck a deal with Joe Roth, then-chair of Walt Disney Studios. He offered them a $10 million budget.[5]

Casting

Anderson and Wilson wrote the role of Mr. Blume with Bill Murray in mind, but doubted they could get the script to him.[9] Murray's agent was a fan of Anderson's first film, Bottle Rocket, and urged the actor to read the script for Rushmore. Murray liked it so much that he agreed to work for scale,[10] which Anderson estimated to be around $9,000.[11] The actor was drawn to Anderson and Wilson's "precise" writing and felt that a lot of the film was about "the struggle to retain civility and kindness in the face of extraordinary pain. And I've felt a lot of that in my life".[12] Anderson created detailed storyboards for each scene but was open to Murray's knack for improvisation.[5]

Cast directors considered 1,800 teenagers from the United States, Canada, and Britain for the role of Max Fischer before finding Jason Schwartzman.[10] In October 1997, approximately a month before principal photography was to begin, a casting director for the film met the 17-year-old actor at a party thanks to his cousin and filmmaker Sofia Coppola.[13] He came to his audition wearing a prep-school blazer and a Rushmore patch he had made himself.[10] Anderson almost did not make the film when he could not find an actor to play Max but felt that Schwartzman "could retain audience loyalty despite doing all the crummy things Max had to do".[8] Anderson originally pictured Max, physically, as Mick Jagger at age 15,[7] to be played by an actor like Noah Taylor in the Australian film Flirting - "a pale, skinny kid".[14] When Anderson met Schwartzman, he reminded Anderson much more of Dustin Hoffman and decided to go that way with the character.[7] Anderson and the actor spent weeks together talking about the character, working on hand gestures and body language.[5]

Principal photography

Filming began in November 1997.[5] On the first day of principal photography, Anderson delivered his directions to Murray in a whisper so that he would not be embarrassed if the actor shot him down. However, the actor publicly deferred to Anderson, hauled equipment, and when Disney denied the director a $75,000 shot of Max and Mr. Blume riding in a helicopter, Murray gave Anderson a blank check to cover the cost, although ultimately the scene was never shot.[10]

At one point, Anderson toyed with the idea of shooting the private school scenes in England and the public school scenes in Detroit in order to "get the most extreme variation possible," according to the director.[15] The film was shot in and around Houston, Texas where Anderson grew up. His high school alma mater, St. John's School, was used for the picturesque setting of Rushmore Academy.[5] Lamar High School in Houston was used to depict Grover Cleveland High School, the public school. In real life, the two schools are across the street from each other.[15] Richard Connelly of the Houston Press said that the Lamar building "was ghetto'd up to look like a dilapidated inner-city school."[16] Many scenes were also filmed at North Shore High School. The film's widescreen, slightly theatrical look was influenced by Roman Polanski's Chinatown.[15] Anderson also cites The Graduate and Harold and Maude as cinematic influences on Rushmore.[17]

Soundtrack

Wes Anderson originally intended for the film's soundtrack to be entirely made up of songs by The Kinks, feeling the music suited Max's loud and angry nature, and because Max was initially envisioned to be a British exchange student. However, while listening to a compilation of other British Invasion songs on set, the soundtrack gradually evolved until only one song by the Kinks remained in the film ("Nothin' in the World Can Stop Me Worryin' 'Bout That Girl"). According to Anderson, "Max always wears a blazer and the British Invasion sounds like music made by guys in blazers, but still rock 'n' roll".[17] In his review for Entertainment Weekly, Rob Brunner gave the soundtrack record an "A-" rating and wrote, "this collection won't make much sense if you haven't seen the movie. But for anyone who left the theater singing along to the Faces' "Ooh La La", it's an essential soundtrack".[18]

Release

Rushmore had its world premiere at the 25th Telluride Film Festival in 1998 where it was one of the few studio films to be screened and be well received by critics and audiences.[19] The film was also screened at the 1998 New York Film Festival and the Toronto Film Festival where it was a hit with critics.[20][21] The film opened in New York City and Los Angeles for one week in December in order to be eligible for the Academy Awards.[10]

Box office

Rushmore opened for a week at single theaters in New York City and Los Angeles on December 11, 1998. In one weekend, it earned a combined USD $43,666, selling out 18 of 31 showings.[17] The film opened in wide release in 764 theaters on February 19, 1999, grossing $2.8 million in its first weekend and went on to make $17.1 million.

Critical response

The film received an 89% "certified fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 102 reviews with an average rating of 8.1 out of 10 with the consensus "This cult favorite is a quirky coming of age story, with fine, off-kilter performances from Jason Schwartzman and Bill Murray."[22] The film also has a score of 86 on Metacritic based on 31 reviews.[23]

In his review for the Daily News, film critic Dave Kehr praised Rushmore as "a magnificent work: the best and most beautiful movie of 1998".[24] USA Today gave the film three out of four stars and wrote that Bill Murray was "at his off-kilter best".[25] Todd McCarthy, in his review for Variety, wrote, "The deep-focus widescreen compositions possess an unusual clarity that adds details and endows the action and humor with exceptional vividness".[26] Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote, "Anderson and Wilson are good offbeat filmmakers ... But their film seems torn between conflicting possibilities: It's structured like a comedy, but there are undertones of darker themes, and I almost wish they'd allowed the plot to lead them into those shadows".[27] In his review for Time, Richard Schickel praised Rushmore as "an often deft, frequently droll little movie turns into an increasingly desperate juggling act, first trying to keep too many dark and weighty emotional objects aloft, then trying to bring them back to hand in a graceful and satisfying way".[28]

In her review for New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote, "It's a particular treat for its skewed, hilarious memories of a cutthroat boyhood".[29] In his review for The Independent, Anthony Quinn said of Schwartzman that "he perfectly captures the poignancy of a character who understands his failings but hasn't yet the emotional resources to conquer them".[30] In her review for the Washington Post, Rita Kempley praised Schwartzman's performance for winning "sympathy and a great deal of affection for Max, never mind that he could grow into Sidney Blumenthal".[31] Entertainment Weekly gave Rushmore an "A" rating and wrote, "Anderson concentrates on beautifully disciplined filmmaking, employing 1960s British Invasion hits . . . to further define Max's adolescent dislocation".[32] Jonathan Rosenbaum, in his review for the Chicago Reader, wrote, "To their credit, Anderson and Wilson share none of the class snobbery that subtly infuses much of Salinger's work ... But like Salinger they harbor a protective gallantry toward their characters that becomes the film's greatest strength and its greatest weakness".[33]

A lifelong fan of film critic Pauline Kael, Anderson arranged a private screening of Rushmore for the retired writer. Afterwards, she told him, "I genuinely don't know what to make of this movie".[34] It was a nerve-wracking experience for Anderson but Kael did like the film and told others to see it.[14] Anderson and Jason Schwartzman traveled from Los Angeles to New York City and back on a touring bus to promote the film.[8] The tour started on January 21, 1999 and went through 11 cities in the United States.[7]

In Time Out New York, Andrew Johnston wrote: "A breezy comedy about the grey area between adolescence and adulthood, Rushmore makes good on the promise of Wes Anderson's Bottle Rocket — and then some. Thanks to stellar performances and the director's original comic vision, it's easily one of the year's finest films. ... Rushmore is somewhat indebted to Harold and Maude and similar comedies of that era, but the complexity of Max and the audacity of the film's set pieces place it in a league of its own."[35]

Awards and nominations

Rushmore was nominated for two Independent Spirit Awards - Wes Anderson for Best Director and Bill Murray for Best Supporting Actor with the actor winning.[36][37] Murray was also nominated in the Best Supporting Actor category for the Golden Globes.[12]

The Los Angeles Film Critics Association named Bill Murray Best Supporting Actor of the year for his performance in Rushmore. Wes Anderson was named the New Generation honoree.[38] The National Society of Film Critics also named Murray as Best Supporting Actor of the year as did the New York Film Critics.[12][39] Film critic David Ansen ranked Rushmore the 10th best film of 1998.[40] Spin hailed the film as "the best comedy of the year".[7]

Rushmore is number 34 on Bravo's "100 Funniest Movies". The film was also ranked #20 on Entertainment Weekly magazine's "The Cult 25: The Essential Left-Field Movie Hits Since '83" list[41] and ranked it #10 on their Top 25 Modern Romances list.[42]

Rushmore was one of the 400 nominated films for the American Film Institute list AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)[43]

Home media

Buena Vista Home Entertainment released an edition of the film on June 29, 1999 with no supplemental material. This was followed by a special edition on January 18, 2000 by The Criterion Collection with remastered picture and sound along with various bonus features, including an audio commentary by Wes Anderson, Owen Wilson and Jason Schwartzman, a behind-the-scenes documentary by Eric Chase Anderson, Anderson and Murray being interviewed on The Charlie Rose Show, and theatrical "adaptations" of Armageddon, The Truman Show and Out of Sight, staged specially for the 1999 MTV Movie Awards by the Max Fischer Players.

A Criterion Collection Blu-ray was released on November 22, 2011.

References

- ↑ "Rushmore". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ↑ Rushmore — "foreign". On boxofficemojo.com

- ↑ The 100 Best Films of the 1990s — "Rushmore". On slantmagazine.com

- ↑ The 30 coolest films ever — "Rushmore". On shortlist.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Winters, Laura (January 31, 1999). "An Original at Ease in the Studio System". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Michael (February 5, 1999). "The Heads of Rushmore". Washington Post. pp. N41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Graham, Renee (February 7, 1999). "On the Road for Rushmore". Boston Globe. pp. N7.

- 1 2 3 Arnold, Gary (February 5, 1999). "Pair on Bus Tout Rushmore and its Teen Protagonist". Washington Times. pp. C12.

- ↑ "Oddball Vision Hits the Fast Lane". Toronto Star. February 7, 1999.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Giles, Jeff (December 7, 1998). "A Real Buddy Picture". Newsweek. p. 72.

- ↑ Bates, Rebecca (November 26, 2013). "The Wes Anderson Collection Is a Gorgeous Look at the Filmmaker's Inspirations". Architectural Digest (Condé Nast). Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Hirschberg, Lynn (January 31, 1999). "Bill Murray, In All Seriousness". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Tahaney, Ed (February 7, 1999). "Playing a Nerd to the Max". Daily News. p. 12.

- 1 2 Lee, Chris (January 21, 1999). "Teacher's Pet". Salon.com (web.archive.org). Archived from the original on 2000-10-25. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- 1 2 3 Linehan, Hugh (August 28, 1999). "Latin Lessons for Today's America". Irish Times. p. 64.

- ↑ Connelly, Richard. "The 7 Best-Looking High Schools in Houston." Houston Press. Tuesday May 22, 2012. 1. Retrieved on May 27, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Westbrook, Bruce (January 31, 1999). "Rushmore's New Face On Top of the Mountain". Houston Chronicle.

- ↑ Brunner, Rob (March 5, 1999). "Rushmore". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

- ↑ Cox, Dan (September 8, 1998). "Rushmore Rocks Telluride". Variety. p. 1.

- ↑ Roman, Monica (August 17, 1998). "Foreign Vest, U.S. Indies Pepper New York Lineup". Variety. p. 15.

- ↑ Kelly, Brendan; Monica Roman (September 21–27, 1998). "New Luster for Toronto". Variety. p. 9.

- ↑ Rushmore (1998). On rottentomatoes.com

- ↑ Rushmore. On metacritic.com

- ↑ Kehr, Dave (December 11, 1998). "Rushmore A Monumental Triumph". Daily News. p. 74.

- ↑ Wloszczyna, Susan (December 11, 1998). "Rushmore Comic Head-of-Class Act". USA Today. pp. 15E.

- ↑ McCarthy, Todd (September 14–20, 1998). "Rocket Men Carve Dark, Brainy Comedy". Variety. p. 33. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (February 5, 1999). "Rushmore". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard (December 14, 1998). "Class Clowns". Time. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (October 9, 1998). "Most Likely to Succeed? Or Annoy?". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Quinn, Anthony (August 20, 1999). "Murray, King of the Nerds". The Independent. p. 14.

- ↑ Kempley, Rita (February 5, 1999). "At the Head of Its Class". Washington Post. pp. C1.

- ↑ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (December 18, 1998). "Class Struggle". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "In a World of His Own". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- ↑ Anderson, Wes (January 31, 1999). "My Private Screening with Pauline Kael". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Time Out New York, December 10–17, 1998, p. 95.

- ↑ Klady, Leonard (January 11–17, 1999). "Schrader's Affliction Wows Indie Spirit Noms". Variety. p. 40. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Puig, Claudia (March 22, 1999). "Gods and Cast Rewarded for their Independent Spirit". USA Today. pp. 3D.

- ↑ Klady, Leonard (December 14, 1998). "L.A. Crix Salute Ryan". Variety. p. 1. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Carr, Jay (January 4, 1999). "National Film Critics Tap Out of Sight". Boston Globe. pp. D3.

- ↑ Ansen, David (January 11, 1999). "Love! Valor! And Hair Gel!". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ "The Cult 25: The Essential Left-Field Movie Hits Since '83". Entertainment Weekly. September 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ↑ "Top 25 Modern Romances". Entertainment Weekly. February 8, 2002. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ↑ AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) Ballot

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rushmore |

- Rushmore at the Internet Movie Database

- Rushmore at AllMovie

- Rushmore at Rotten Tomatoes

- Rushmore at Metacritic

- Rushmore at Box Office Mojo

| ||||||||||||||||

|