Fugitive slaves in the United States

The phenomenon of slaves running away and seeking to gain freedom is as old as the institution of slavery itself. In the history of slavery in the United States, "fugitive slaves" (also known as runaway slaves) were slaves who left their master and traveled without authorization; generally they tried to reach states or territories where slavery was banned, including Canada. Most slave law tried to control slave travel by requiring them to carry official passes if traveling without a master.

Passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increased penalties against fugitive slaves and people who aided them. Because of this, fugitive slaves tried to leave the United States altogether, traveling to Canada or Mexico. During the time slavery was legal in the United States, approximately 100,000 slaves escaped to freedom.[1]

History

The United States Constitution included language to protect slavery, and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 implemented rules requiring citizens to aid in the return of escaped slaves to their owners. In practice, both citizens and governments of free states often supported the escape of fugitive slaves. Fugitive slaves early in U.S. were sought out just as they were through the Fugitive slave law years, but early efforts included only Wanted posters, flyers etc.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 strengthened provisions for the recapture of slaves, and offered them no protection in the justice system. Bounty hunters and civilians could lawfully capture escaped slaves in the North, or any other place, using little more than an affidavit, and return them to the Slave master.

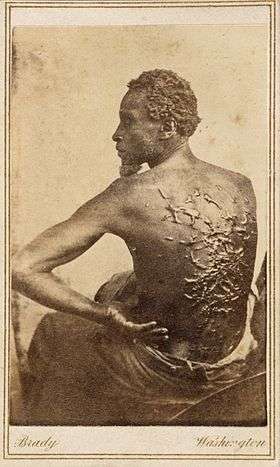

Many escaped slaves upon return were to face harsh punishments such as amputation of limbs, whippings, branding, and many other horrible acts.[2]

Individuals who aided fugitive slaves were charged and punished under this law. In the case of Ableman v. Booth, Booth was charged with aiding Glover's escape in Wisconsin by preventing his capture by Federal Marshals. The Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was unconstitutional for requiring states to go against their own laws in protecting slavery. Ableman v. Booth was appealed by the federal government to the US Supreme Court, which upheld the constitutionality of the Act.[3]

Many states tried to nullify the new slave act or prevent capture of escaped slaves by setting up new laws to protect their rights. One of the most notable is the Massachusetts Liberty Act. This Act was passed in order to keep escaped slaves from being returned to their masters through abduction by Federal Marshals or bounty hunters.[4]

The Underground Railroad had developed as a way in which free blacks and whites (and sometimes slaves) aided fugitive slaves to reach freedom in northern states. "Stations" were set up in private homes, churches, caves, barns and hidden places, to give escaped slaves places to stay on their way. People who maintained the stations provided food, clothing and shelter to the fugitives, and sometimes guides along the way. This is probably one of the most well known ways that abolitionists aided slaves out of the south and into northern states. In this manner the slaves would go from house to house of either whites or freed blacks where they would receive shelter, food, clothing etc.

Now when the slaves were found gone, most masters did everything they could to find their lost “property.” Flyers would be put up, posses to find him/her would be sent out, and under the new Fugitive Slave Act they could now send federal marshals into the north to extract them. This new law also brought up bounty hunters to the game of returning slaves to their masters; a “slave” who had already been freed could be brought back into the south to be sold back into slavery if he/she was without freedom papers. In 1851 there was a case of a black coffeehouse waiter who was snatched by federal marshals on behalf of John Debree, who claimed the man to be his property.[5] Even though the man had escaped earlier, his case was brought before the Massachusetts supreme court to be tried.

The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of black and white abolitionists between 1816 and the end of the Civil War who helped fugitive slaves escape to freedom. Members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), Baptists, Methodists and other religious sects helped in operating the Underground Railroad. The underground Railroad was initially an escape route that would assist fugitive enslaved African Americans in arriving in the Northern states; however, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, as well as other laws aiding the southern states in the capturing of runaway slaves, resulting in the Underground railroad being used as a mechanism to reach Canada. Canada was a Safe-haven for African American slaves because Canada had already abolished slavery by the year 1783. Blacks in Canada were also provided equal protection under the law. The well-known Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman is said to have led approximately 300 slaves to Canada. [6]

Notable people who gained or assisted others in gaining freedom via the Underground Railroad include:

- Henry "Box" Brown

- Elizabeth Margaret Chandler

- Levi Coffin

- Frederick Douglass

- Calvin Fairbank

- Thomas Garrett

- Laura Smith Haviland

- Lewis Hayden

- Josiah Henson

- Isaac Hopper

- Roger Hooker Leavitt

- Samuel J. May

- John Parker

- John Wesley Posey

- John Rankin

- Alexander Milton Ross

- David Ruggles

- Samuel Seawell

- William Still

- Sojourner Truth

- Harriet Tubman

- Charles Augustus Wheaton

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, part of the Compromise of 1850, was a law enacted by the Congress that declared that all fugitive slaves should be returned to their masters. Because the South agreed to have California enter as a free state, The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was created. The act was passed on September 18, 1850, and it was repealed on June 28, 1864. The act strengthened the authority of the federal government in the capturing of fugitive slaves. The act authorized federal marshals to require northern citizen bystanders to aid in the capturing of alleged runaways. Many northerners perceived the legislation as a way in which the federal government overstepped its boundaries of authority, due to the fact that the legislation could be used to force northerners to act against their anti-slavery beliefs. Many northern states eventually passed Personal Liberty Laws that prevented the kidnapping of alleged runaway slaves; however, in the court case known as Priggs v. Pennsylvania, the personal liberty laws were ruled unconstitutional on the grounds that the capturing of fugitive slaves was a federal matter in which states did not have the power to interfere.[7]

Harriet Tubman

One of the most notable fugitive slaves of American history and conductors of the Underground Railroad is Harriet Tubman. Born into slavery in Dorchester County, Maryland around 1822, Tubman as a young adult escaped from her master’s plantation in 1849. Between 1850 and 1860, she returned to the South numerous times to help parties of other slaves to freedom, guiding them through the lands she knew well. She aided an estimated 300 persons to escape from slavery, including her parents. During this time, there was a $40,000 bounty for her, payable to anyone who could capture her and bring her back to slavery. Many people called her the “Moses of her people.” During the American Civil War, Harriet Tubman also worked as a spy and as a nurse at Port Royal, South Carolina.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fugitive slaves. |

- Abolitionism

- Article Four of the United States Constitution

- Drapetomania, a supposed mental illness that caused black slaves to flee captivity

- Fugitive Slave Acts

- Slave Trade Compromise and Fugitive Slave Clause

- Maroon (people), African refugees who escaped slavery in the Americas and formed settlements

References

- ↑ Renford, Reese (2011). "Canada; The Promised Land for Slaves". Western Journal of Black Studies 35 (3): 208-217.

- ↑ Bland, Lecater Bland, Voices of the Fugitives: Run-away Slave Stories and Their Fictions of Self Creation Greenwood Press, 2000

- ↑ Archived November 20, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Archived October 10, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Schwarz, Frederic D. American Heritage, February/March 2001, Vol. 52 Issue 1, p96

- ↑ Reese, Renford (2011). "Canada; The Promised Land for Slaves". Western Journal of Black Studies.

- ↑ White, Deborah (2013). Freedom on my Mind. Boston Mass: Bedford/St Martins. p. 286. ISBN 9780312648831.

Further reading

- Baker, H. Robert, “The Fugitive Slave Clause and the Antebellum Constitution,” Law and History Review 30 (Nov. 2012), 1133–74.

- Bland, Lecater. Voices of the Fugitives: Run-away Slave Stories and Their Fictions of Self Creation (Greenwood Press, 2000)

External links

- Maap.columbia.edu

- Spartacus-educational.com

- Nps.gov

- Slavenorth.com

- Pbs.org

- Slaveryamerica.org

- Library.thinkquest.org

- Query.nytimes.com

- Wicourts.gov

- Eca.state.gov

- "Millard Fillmore on the Fugitive Slave and Kansas-Nebraska Acts: Original Letter", Shapell Manuscript Foundation