Rubber elasticity

Rubber elasticity, a well-known example of hyperelasticity, describes the mechanical behavior of many polymers, especially those with cross-links.

Thermodynamics

Temperature affects the elasticity of elastomers in an unusual way. When the elastomer is assumed to be in a stretched state, heating causes them to contract. Vice versa, cooling can cause expansion.[1] This can be observed with an ordinary rubber band. Stretching a rubber band will cause it to release heat (press it against your lips), while releasing it after it has been stretched will lead it to absorb heat, causing its surroundings to become cooler. This phenomenon can be explained with the Gibbs Free Energy. Rearranging ΔG=ΔH−TΔS, where G is the free energy, H is the enthalpy, and S is the entropy, we get TΔS=ΔH−ΔG. Since stretching is nonspontaneous, as it requires external work, TΔS must be negative. Since T is always positive (it can never reach absolute zero), the ΔS must be negative, implying that the rubber in its natural state is more entangled (with more microstates) than when it is under tension. Thus, when the tension is removed, the reaction is spontaneous, leading ΔG to be negative. Consequently, the cooling effect must result in a positive ΔH, so ΔS will be positive there.[2][3]

The result is that an elastomer behaves somewhat like an ideal monatomic gas, inasmuch as (to good approximation) elastic polymers do not store any potential energy in stretched chemical bonds or elastic work done in stretching molecules, when work is done upon them. Instead, all work done on the rubber is "released" (not stored) and appears immediately in the polymer as thermal energy. In the same way, all work that the elastic does on the surroundings results in the disappearance of thermal energy in order to do the work (the elastic band grows cooler, like an expanding gas). This last phenomenon is the critical clue that the ability of an elastomer to do work depends (as with an ideal gas) only on entropy-change considerations, and not on any stored (i.e., potential) energy within the polymer bonds. Instead, the energy to do work comes entirely from thermal energy, and (as in the case of an expanding ideal gas) only the positive entropy change of the polymer allows its internal thermal energy to be converted efficiently (100% in theory) into work.

Models

Invoking the theory of rubber elasticity, one considers a polymer chain in a crosslinked network as an entropic spring. When the chain is stretched, the entropy is reduced by a large margin because there are fewer conformations available.[4] Therefore, there is a restoring force, which causes the polymer chain to return to its equilibrium or unstretched state, such as a high entropy random coil configuration, once the external force is removed. This is the reason why rubber bands return to their original state. Two common models for rubber elasticity are the freely-jointed chain model and the worm-like chain model.

Freely-jointed chain model

Polymers can be modeled as freely jointed chains with one fixed end and one free end (FJC model):

where  is the length of a rigid segment,

is the length of a rigid segment,  is the number of segments of length

is the number of segments of length  ,

,  is the distance between the fixed and free ends, and

is the distance between the fixed and free ends, and  is the "contour length" or

is the "contour length" or  . Above the glass transition temperature, the polymer chain oscillates and

. Above the glass transition temperature, the polymer chain oscillates and  changes over time. The probability of finding the chain ends a distance

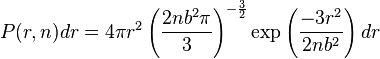

changes over time. The probability of finding the chain ends a distance  apart is given by the following Gaussian distribution:

apart is given by the following Gaussian distribution:

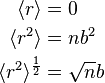

Note that the movement could be backwards or forwards, so the net time average  will be zero. However, one can use the root mean square as a useful measure of that distance.

will be zero. However, one can use the root mean square as a useful measure of that distance.

Ideally, the polymer chain's movement is purely entropic (no enthalpic, or heat-related, forces involved). By using the following basic equations for entropy and Helmholtz free energy, we can model the driving force of entropy "pulling" the polymer into an unstretched conformation. Note that the force equation resembles that of a spring: F=kx.

Note that the elastic coefficient  is temperature dependent. If we increase the rubber temperature, the elastic coefficient also rises. This is the reason why rubber under constant stress shrinks when its temperature increases.

is temperature dependent. If we increase the rubber temperature, the elastic coefficient also rises. This is the reason why rubber under constant stress shrinks when its temperature increases.

Worm-like chain model

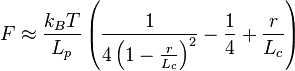

The worm-like chain model (WLC) takes the energy required to bend a molecule into account. The variables are the same except that  , the persistence length, replaces

, the persistence length, replaces  . Then, the force follows this equation:

. Then, the force follows this equation:

Therefore, when there is no distance between chain ends (r=0), the force required to do so is zero, and to fully extend the polymer chain ( ), an infinite force is required, which is intuitive. Graphically, the force begins at the origin and initially increases linearly with

), an infinite force is required, which is intuitive. Graphically, the force begins at the origin and initially increases linearly with  . The force then plateaus but eventually increases again and approaches infinity as the chain length approaches

. The force then plateaus but eventually increases again and approaches infinity as the chain length approaches

See also

References

- ↑ "Thermodynamics of a Rubber Band", American Journal of Physics 31 (5), May 1963: 397–397, Bibcode:1963AmJPh..31..397T, doi:10.1119/1.1969535

- ↑ Rubber Bands and Heat, http://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/HomeExpts/rubberband.html, citing Shakhashiri (1983)

- ↑ Shakhashiri, Bassam Z. (1983), Chemical Demonstrations: A Handbook for Teachers of Chemistry 1, Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-08890-3

- ↑ L.R.G. Treloar (1975), Physics of Rubber Elasticity, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198570271