Louis-François Roubiliac

| Louis-François Roubiliac | |

|---|---|

|

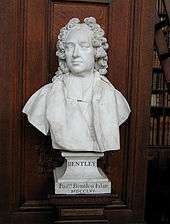

Roubiliac by Joseph Wilton, 1761, National Portrait Gallery, London | |

| Born |

Louis-François Roubillac 1702/1705 Lyon, France |

| Died | 11 January 1762 |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Studio of Balthasar Permoser |

| Known for | Rococo sculpture |

| Spouse(s) | Caroline Magdalene Hélot |

.jpg)

Louis-François Roubiliac (more correctly Roubillac) (1702/1705[1] – 11 January 1762) was a French sculptor who worked in England, one of the four most prominent sculptors in London working in the rococo style,[2] He was described by Margaret Whinney as "probably the most accomplished sculptor ever to work in England".[3]

Life

Roubiliac was born in Lyon. According to J.T. Smith he was trained in the studio of Balthasar Permoser in Dresden, where Permoser, a product of Bernini's workshop, was working for the Protestant Elector of Saxony,[4] and later in Paris, in the studio of his fellow-townsman Nicolas Coustou. Disappointed in receiving second place in the competition for the Prix de Rome, 1730,[5] he received his medal but not the chance to study in Rome; he moved to London instead.[6] In 1735 he married Caroline Magdalene Hélot, a member of the French Huguenot community in London, at St Martin's-in-the-Fields.

In London, he was employed by "Carter, the statuary" but was introduced by Edward Walpole, son of the Prime Minister, to Henry Cheere, who took him on as an assistant. Sir Edward's intervention resulted in the commission for half the busts in the series for Trinity College, Dublin, and for the Argyll monument commission, if Horace Walpole is correct in his Anecdotes of Painting in England.[7]

In 1738 he had a great success with a seated figure of Handel, commissioned by Jonathan Tyers, owner of the Vauxhall Gardens. The statue blends realism and allegory: Handel is shown in modern dress, but plays an Ancient Greek lyre, and has a putto sitting at his feet. It is now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.[8] He was recommended for this commission by Cheere.[9] Its prominent placement in the fashionable pleasure grounds "fixed Roubiliac's fame" as Walpole put it, and he was able to open the studio in St Martin's Lane that he maintained until his death. Roubiliac was a founding member of the St Martin's Lane Academy, a professional association and fraternity of rococo artists that was a forerunner to the Royal Academy. His studio in St Martin's Lane became its meeting room; its members came together again for his funeral.[10]

He earned his living from commissions for portrait busts and monuments for country churches[11] until 1745, when he received the first of his commissions for a funeral monument in Westminster Abbey, for one commemorating the Duke of Argyll (installed 1749).[12] George Vertue was one of the work's many admirers; it showed, he thought, "the greatness of his genius in his invention, design and execution, in every part equal, if not superior, to any others" outshining "for nobleness and skill all those before done by the best sculptors this fifty years past"[13] The mourning figure of Eloquence, the notably unkind John Thomas Smith found to be "such a memorial of his powers, that even his friend Pope could not have equalled it by an epitaph".

Even when the patrons were prominent, the churches in which the monuments were installed often lay deep in the English countryside: the monuments to the Duke of Montagu (1752), and of his wife Mary (1753), are in the church at Warkton, Northamptonshire; Horace Walpole, an inveterate country house visitor, noted them: his verdict was "well-performed and magnificent, but wanting in simplicity".[14]

Neoclassical taste, trained to appreciate svelte line and idealised refinements of nature, did not favour Roubiliac's vigour and immediacy: to J.T. Smith the legs of the figure of Hercules, supporting the bust of Sir Peter Warren in Roubliac's monument in Westminster Abbey (1753) seemed "copied from a chairman's, and the arms from those of a waterman"[15]

About the mid-century Roubiliac was employed for a time as a modeller at the Chelsea porcelain factory, a new outlet for sculptors' talent in Britain; its entrepreneur Nicholas Sprimont stood godfather to the sculptor's daughter Sophie, in 1744.[16] For a friend like Thomas Hudson he was willing to sculpt figures of Painting and Sculpture to ornament a marble chimneypiece in Hudson's house in Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields.[17] For his friend William Hogarth he even carved a portrait of Hogarth's dog "Trump".[18] His second wife (a considerable heiress) having recently died, he took a brief tour to Italy towards the end of 1752 in the company of several artists.[19]

Soon after his death an auction sale of the contents of his studio was held, on 12–15 May 1762, from which Dr Matthew Maty purchased a number of his plaster and terracotta models, which he presented to the newly founded British Museum. Prices were derisory, and when his effects were totalled up, Roubiliac's creditors, J.T. Smith said, had to be satisfied with one shilling sixpence in the pound.[20]

Works

Roubiliac was mainly employed for portrait busts, and from the 1740s especially for sepulchral monuments; these were, in essence, the two outlets for free-standing sculpture in Britain at the time. He also made several full-length portrait sculptures. His most important works in Westminster Abbey are the monuments to the Duke of Argyll (1748) – the work which first established his fame as a sculptor – Handel (1761), Sir Peter Warren, Marshal Wade, and Lady Elizabeth Nightingale (1761).

At Cambridge he made the statues of George I in the Senate House, Cambridge, the Duke of Somerset and Sir Isaac Newton. Trinity College, Cambridge, has a series of busts by him of distinguished members of the college. The statue of George II erected in Golden Square, London, was also his work.

The celebrated bust of William Shakespeare, known as the Davenant bust, in the possession of the Garrick Club, London, must be attributed to Roubiliac. His friend Sir Joshua Reynolds painted a copy of the Chandos Portrait for him.[21] The statue of Shakespeare (1758), a commission from David Garrick to be set up in his garden shrine to Shakespeare at Hampton House, Twickenham, and bequeathed by the actor to the English nation, is in the British Museum; a terracotta model dated 1757 is in collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Notes

- ↑ Dates in Margaret Whinney, Sculpture in Britain, 1530 to 1830, 1981:198.

- ↑ The others being Michael Rysbrack, Peter Scheemakers and Henry Cheere.

- ↑ Whinney 1981:198.

- ↑ Smith 1829.

- ↑ According to Le Roy de Sainte-Croix, Vie et ouvrages de L. F. Roubiliac, sculpteur lyonnais (1695-1762) Paris, 1882. (An extremely rare work, of which a copy is in the National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, it otherwise largely follows Smith 1829) The set subject was a bas-relief of Daniel defending Susannah.

- ↑ Gunnis 1968

- ↑ Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England, vol. III "Statuaries in the Reign of George II"

- ↑ Whinney 1971:77– 8

- ↑ Smith 1829 vol. II:94; the often-repeated cost of 300 guineas reported by K.A. Esdaile was a published estimate for the sculpture and an elaborate architectural niche, never executed (Whinney 1981:454 note 9).

- ↑ Listed in Smith 1829: vol. II:98.

- ↑ The funeral monument for Bishop Hough, in Worcester Cathedral (1747) was admired in 1753 by Horace Walpole, who found its fully "in the Westminster Abbey style"; "it has a dramatic unity of action unknown in the work of Rysbrack, Scheemakers, or Cheere," Margaret Whinney has observed. (Whinney 1981:203).

- ↑ "1745" is the date on the terracotta model, at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

- ↑ Vertue Notebooks, Walpole Society iv:146 quoted by Gunnis 1968.

- ↑ Walpole, Anecdotes.

- ↑ Smith 1829, vol. II;90.

- ↑ Peter Bradshaw (1981). 18th century English porcelain figures, 1745-1795.; many pieces have been attributed to him; see An illustrated catalogue of fifty-eight pieces of fine Chelsea porcelain many modelled by Louis François Roubiliac (circa 1755-1760) in the collection of Henry Edwards Huntington at San Marino, California. 1925. but only Hogarth's pug "Trump" is securely known to be by Roubiliac (J.V.G. Mallet, "Hogarth's pug in porcelain", Victoria & Albert Bulletin (1967:45).

- ↑ Smith 1829, vol II:93; they were bought at Hudson's sale by Joseph Nollekens

- ↑ Gunnis 1968: it was lot 239 in James Brindley's sale at Christie's, 1819.

- ↑ Gunnis 1968; Whinney 1981:.

- ↑ Smith 1829: vol. II:99.

- ↑ It was sold in Roubiliac's sale in a lot of eight paintings that brought just ten shillings; it was identified and rescued by the father of John Flaxman, who immediately resold it for three guineas; the actor Edward Malone subsequently owned it (Smith 1829, vol. II:99).

Bibliography

- Allan Cunningham, The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, vol. 3, pp. 31–67 (London, 1830) the fount of information of later biographies.

- Dutton Cook, Art in England ("A Sculptor's Life in the Past Century") (London, 1869)

- Austin Dobson, "Little Roubiliac," The Magazine of Art 17 (1894:202, 231)

- entry in DNB

- Katherine A.M. Esdaile, Roubiliac's Work at Trinity College Cambridge. Cambridge University Press (1924. reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009) ISBN 978-1-108-00231-8)

- Rupert Gunnis, Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1851 (rev. ed., 1968).

- J.T. Smith, Nollekens and his Times (London, 1829 passim); Smith's father was an assistant in Roubiliac's studio.

- Margaret Whinney, English Sculpture 1720-1830. Victoria and Albert Museum Monograph, HMSO, (London 1971).

- Margaret Whinney, Sculpture in Britain, 1530 to 1830. Pelican History of Art (London,1981)

- William T. Whitley, Artists and Their Friends in England, 1700-1799, 1928.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis-François Roubiliac. |

- "Roubiliac's Handel". Sculpture. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- "Tomb of Sir Joseph and Lady Elizabeth Nightingale". Sculpture. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- "The Laughing Child & The Crying Child". Sculpture. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- Louis-François Roubiliac in American public collections on the French Sculpture Census website

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

|