Rottenacker

| Rottenacker | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Rottenacker | ||

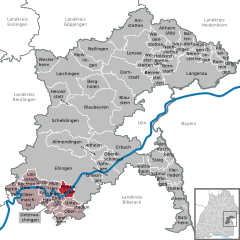

Location of Rottenacker within Alb-Donau-Kreis district

| ||

| Coordinates: 48°14′8″N 9°41′22″E / 48.23556°N 9.68944°ECoordinates: 48°14′8″N 9°41′22″E / 48.23556°N 9.68944°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Baden-Württemberg | |

| Admin. region | Tübingen | |

| District | Alb-Donau-Kreis | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 10.29 km2 (3.97 sq mi) | |

| Population (2013-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 2,075 | |

| • Density | 200/km2 (520/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 89616 | |

| Dialling codes | 07393 | |

| Vehicle registration | UL | |

| Website | www.rottenacker.de | |

Rottenacker is a village in the district of Alb-Donau in Baden-Württemberg in Germany.

History

The Separatists

During the late 18th century the Radical Pietist movement throughout the Duchy of Wuerttemberg increased again after having diminished over the previous decades. Many Pietists separated from church for religious reasons. In Wuerttemberg, where Rottenacker belonged to, those religious dissenters were generally known as 'separatists'. Since 1785 the linen weaver George Rapp from Iptingen became the most important leader of the Separatists in Wuerttemberg, directing about 2,000 followers. When Rapp emigrated to the United States in 1803, a Separatist group from Rottenacker took over the leading role within the movement. It had been initiated in 1800 by a farmgirl named Barbara Grubenmann from Teufen in the Swiss canton Appenzell-Ausserrhoden south of Lake Constance who had come to Rottenacker. About 70 inhabitants of the village separated from church. From the beginning political ideas played an important role when the separatists insulted the ruler of Wuerttemberg, the Elector Friedrich (1797-1803 Duke Friedrich II, 1806-1816 King of Wuerttemberg) and his officials. In May 1804, the Elector sent military to the villages of Rottenacker, Dettingen unter Teck, Horrheim and Boll. The most prominent Separatists were arrested and led to the Fortrass of Asperg near Ludwigsburg in central Wuerttemberg where many of them remained prisoners for a long time. When some parents refused to send their children to school the pupils were taken away to the orphanage at Stuttgart, the capital of Wuerttemberg.

In 1811, some Separatists from Rottenacker bought the local 'Vogthaus' (today the Protestant ministry) near the church where they lived in a community of goods. Six years later, together with Separatists from other villages, they acquired an estate named Brandenburg near the border to Bavaria where they intended to found a community based on their religious principles. However, King Friedich of Wuerttemberg refused permission.

Therefore, a group of Separatists from Wuerttemberg led by Joseph Michael Bimeler from Ulm and Stephan Huber from Rottenacker emigrated to the United States in 1817 and went to Ohio where they founded a communal society at Zoar. There, they lived in a community of goods where all private property was abolished. After Joseph Bimeler died in 1853, a younger generation was no more willing to share their property with others, and therefore the Zoar Society was dissolved in 1898.

Today, Zoar Village is a museum where many of the buildings from the Separatist era can still be visited.

Persons

- Johannes Breimaier (born January 24, 1776 at Rottenacker, died August 15, 1834 at Zoar, Ohio, separatist. He initiated the community of goods in Zoar in 1819. A newspaper report in English about Zoar and other religious communities in the United States made a strong impression on Friedrich Engels who was busy writing the Communist Manifesto published in 1848.

Literature

- Eberhard Fritz: Separatisten und Separatistinnen in Rottenacker. Eine örtliche Gruppe als Zentrum eines „Netzwerks“ im frühen 19. Jahrhundert. In: Blätter für württembergische Kirchengeschichte 98/1998. S. 66-158.

- Eberhard Fritz: Roots of Zoar, Ohio, in early 19th century Württemberg: The Separatist group of Rottenacker and its Circle. Part one. Communal Societies 22/2002. p. 27-44. Part two. Communal Societies 23/2003. p. 29-44.

References

|