Rosser's trick

- For the theorem about the sparseness of prime numbers, see Rosser's theorem. For a general introduction to the incompleteness theorems, see Gödel's incompleteness theorems.

In mathematical logic, Rosser's trick is a method for proving Gödel's incompleteness theorems without the assumption that the theory being considered is ω-consistent (Smorynski 1977, p. 840; Mendelson 1977, p. 160). This method was introduced by J. Barkley Rosser in 1936, as an improvement of Gödel's original proof of the incompleteness theorems that was published in 1931.

While Gödel's original proof uses a sentence that says (informally) "This sentence is not provable", Rosser's trick uses a formula that says "If this sentence is provable, there is a shorter proof of its negation".

Background

Rosser's trick begins with the assumptions of Gödel's incompleteness theorem. A theory T is selected which is effective, consistent, and includes a sufficient fragment of elementary arithmetic.

Gödel's proof shows that for any such theory there is a formula ProofT(x,y) which has the intended meaning that y is a natural number code (a Gödel number) for a formula and x is the Gödel number for a proof, from the axioms of T, of the formula encoded by y. (In the remainder of this article, no distinction is made between the number y and the formula encoded by y, and the number coding a formula φ is denoted #φ). Furthermore, the formula PvblT(y) is defined as ∃x ProofT(x,y). It is intended to define the set of formulas provable from T.

The assumptions on T also show that it is able to define a negation function neg(y), with the property that if y is a code for a formula φ then neg(y) is a code for the formula ¬φ. The negation function may take any value whatsoever for inputs that are not codes of formulas.

The Gödel sentence of the theory T is a formula φ, sometimes denoted GT such that T proves φ ↔ ¬PvblT(#φ). Gödel's proof shows that if T is consistent then it cannot prove its Gödel sentence; but in order to show that the negation of the Gödel sentence is also not provable, it is necessary to add a stronger assumption that the theory is ω-consistent, not merely consistent. For example, the theory T=PA+¬GPA proves ¬GT. Rosser (1936) constructed a different self-referential sentence that can be used to replace the Gödel sentence in Gödel's proof, removing the need to assume ω-consistency.

The Rosser sentence

For a fixed arithmetical theory T, let ProofT(x,y) and neg(x) be the associated proof predicate and negation function.

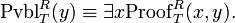

A modified proof predicate ProofRT(x,y) is defined as:

which means that

This modified proof predicate is used to define a modified provability predicate PvblRT(y):

Informally, PvblRT(y) is the claim that y is provable via some coded proof x such that there is no smaller coded proof of the negation of y. Under the assumption that T is consistent, for each formula φ the formula PvblRT(#φ) will hold if and only if PvblT(#φ) holds. However, these predicates have different properties from the point of view of provability in T.

Using the diagonal lemma, let ρ be a formula such that T proves ρ ↔ ¬ PvblRT(#ρ). The formula ρ is the Rosser sentence of the theory T.

Rosser's theorem

Let T be an effective, consistent theory including a sufficient amount of arithmetic, with Rosser sentence ρ. Then the following hold (Mendelson 1977, p. 160):

- T does not prove ρ

- T does not prove ¬ρ.

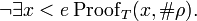

The proof of (1) is as in Gödel's proof of the first incompleteness theorem. The proof of (2) is more involved. Assume that T proves ¬ρ and let e be a natural number coding for a proof of ¬ρ in T. Because T is consistent, there is no code for a proof of ρ in T, so ProofRT(e,neg(#ρ)) will hold (because there is no z < e that codes a proof of ρ).

The assumption that T includes enough arithmetic ensures that T will prove

and (using the assumption of consistency and the fact that e is a natural number)

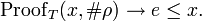

From the latter formula, the assumptions on T show that it proves

Thus T proves

But this last formula is provably equivalent to ρ in T, by definition of ρ, which means that T proves ρ. This is a contradiction, as T was assumed to prove ¬ρ and assumed to be consistent. Thus T cannot prove ¬ρ under the assumption T is consistent.

References

- Mendelson (1977), Introduction to Mathematical Logic

- Smorynski (1977), "The incompleteness theorems", in Handbook of Mathematical Logic, Jon Barwise, Ed., North Holland, 1982, ISBN 0-444-86388-5

- Rosser (1936), "Extensions of some theorems of Gödel and Church", Journal of Symbolic Logic, v. 1, pp. 87–91.

External links

- Avigad (2007), "Computability and Incompleteness", lecture notes.

![\mathrm{Proof}^R_T(x,y) \equiv \mathrm{Proof}_T(x,y) \land \lnot \exists z \leq x [ \mathrm{Proof}_T(z,\mathrm{neg}(y))],](../I/m/4b309c98842274728d310146d9d15e86.png)

![\lnot \mathrm{Proof}^R_T(x,y) \equiv \mathrm{Proof}_T(x,y) \to \exists z \leq x [ \mathrm{Proof}_T(z,\mathrm{neg}(y))].](../I/m/685a15e33d14f892bded3366d87f6e97.png)

![\forall x ( e \leq x \to \exists z \leq x [ \mathrm{Proof}_T (z,\mathrm{neg}(\#\rho))],](../I/m/ba1f3ed671138066115aad65ec8781e4.png)

![\forall x [\mathrm{Proof}_T(x, \#\rho) \to \exists z \leq x \mathrm{Proof}_T (z,\mathrm{neg}(\#\rho))].](../I/m/182248e76dfd5a470bcc1660e70eb187.png)