Romanization of Chinese

| Chinese romanization |

|---|

| Mandarin |

| Wu |

|

|

| Yue |

| Southern Min |

| Eastern Min |

| Northern Min |

| Pu-Xian Min |

| Hakka |

| Gan |

| See also |

The Romanization of Chinese is the use of the Latin alphabet to write Chinese. Chinese uses a logographic script, and its characters do not represent phonemes directly. There have been many systems using Roman characters to represent Chinese throughout history. Linguist Daniel Kane recalls, "It used to be said that sinologists had to be like musicians, who might compose in one key and readily transcribe into other keys."[1] However, Hanyu Pinyin has become the international standard since 1982. Other well-known systems include Wade-Giles and Yale Romanization.

There are many uses for Chinese Romanization. It serves as a useful tool for foreign learners of Chinese by indicating the pronunciation of unfamiliar characters. It can also be helpful for clarifying pronunciation — Chinese pronunciation is an issue for some speakers of other mutually unintelligible Chinese varieties who do not speak Mandarin fluently. Standard keyboards such as QWERTY are designed for the Latin alphabet, often making the input of Chinese characters into computers difficult. Chinese dictionaries have complex sorting rules for characters, and romanization systems can simplify the problem by listing the characters by their Latin form alphabetically.

Romanization systems for other Chinese varieties are indicated in the information box on the right side of this page.

Background

The Indian Sanskrit grammarians who went to China two thousand years ago to work on the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese and the transcription of Buddhist terms into Chinese, discovered the "initial sound", "final sound", and "suprasegmental tone" structure of spoken Chinese syllables. This understanding is reflected in the precise Fanqie system, and it is the core principle of all modern systems. While the Fanqie system was ideal for indicating the conventional pronunciation of single, isolated characters in written Classical Chinese literature, it was unworkable for the pronunciation of essentially polysyllabic, colloquial spoken Chinese varieties, such as Mandarin.

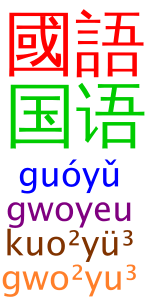

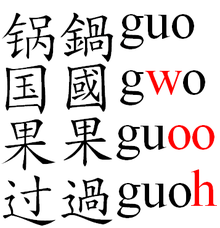

Aside from syllable structure, it is also necessary to indicate tones in Chinese romanization. Tones distinguish the definition of all morphemes in Chinese, and the definition of a word is often ambiguous in the absence of tones. Certain systems such as Wade-Giles indicate tone with a number following the syllable: ma1, ma2, ma3, ma4. Others, like Pinyin, indicate the tone with diacritics: mā, má, mǎ, mà. Still, the system of Gwoyeu Romatzyh (National Romanization) bypasses the issue of introducing non-letter symbols by changing the letters within the syllable, as in mha, ma, maa, mah, each of which contains the same vowel, but a different tone.

Uses

Non-Chinese

- Making the actual pronunciation conventions of spoken Chinese intelligible to non-Chinese-speaking students, especially those with no experience of a tonal language.

- Making the syntactic structure of Chinese intelligible to those only familiar with Latin grammar.

- Transcribing the citation pronunciation of specific Chinese characters according to the pronunciation conventions of a specific European language, to allow the insertion of that Chinese pronunciation into a Western text.

- Allowing instant communication in "colloquial Chinese" between Chinese and non-Chinese speakers via a phrase-book.

Chinese

- Identifying the specific pronunciation of a character within a specific context[lower-alpha 1] (e.g. xíng (行 to walk; behaviour, conduct) or háng (a store)). Such a system has to work vertically down the page, right-to-left, and left-to-right.[lower-alpha 2]

- Reciting a Chinese text in Mandarin for some literate speakers of another mutually unintelligible Chinese varieties, such as Cantonese, who do not speak Mandarin fluently.

- Learning Classical or Modern Chinese by native Mandarin speakers.

- Use with a standard QWERTY keyboard.

- Replacing Chinese characters to bring functional literacy to illiterate native Mandarin speakers.

- Book indexing, dictionary entry sorting, and cataloguing in general.

- Teaching spoken and written Chinese to foreigners.

Non-Chinese systems

The Wade, Wade-Giles, and Postal systems still appear in the European literature, but generally only within a passage cited from an earlier work. Most European language texts use the Chinese Hanyu Pinyin system (usually without tone marks) since 1979 as it was adopted by the People's Republic of China.[lower-alpha 3]

Missionary systems

Early Roman Catholic missionaries from Europe used Latin as their international language, and the Latinized names of two of the most influential Chinese thinkers are still used today. "Confucius" was their Latin rendering of the Chinese Kǒng Fūzǐ (孔夫子, lit. "Master Kong"), removing the lightly pronounced -g and appending the Latin masculine ending -us. Similarly, Mèngzǐ (孟子, lit. "Master Meng") became "Mencius".

The first consistent system for transcribing Chinese words in Latin alphabet is thought to have been designed in 1583-88 by Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri for their Portuguese-Chinese dictionary — the first ever European-Chinese dictionary. Unfortunately, the manuscript was misplaced in the Jesuit Archives in Rome, and not re-discovered until 1934. The dictionary was finally published in 2001.[3][4] During the winter of 1598, Ricci, with the help of his Jesuit colleague Lazzaro Cattaneo (1560–1640), compiled a Chinese-Portuguese dictionary as well, in which tones of the romanized Chinese syllables were indicated with diacritical marks. This work has also been lost but not rediscovered.[3]

Cattaneo's system, with its accounting for the tones, was not lost, however. It was used e.g. by Michał Boym and his two Chinese assistants in the first publication of the original and Romanized text of the Nestorian Stele, which appeared in China Illustrata (1667) — an encyclopedic-scope work compiled by Athanasius Kircher.[5]

In 1626 the Jesuit missionary Nicolas Trigault came up with a romanization system in his Xiru Ermu Zi (simplified Chinese: 西儒耳目资; traditional Chinese: 西儒耳目資; pinyin: Xīrú ěrmù zī; literally: "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati").

The Dominican missionary Francisco Varo created his up romanization system in his 1670 Portuguese language "Vocabulario da lingoa mandarina" and posthumously published 1692 Spanish language "Vocabulario de la lengua Mandarina" and 1703 "Arte de la lengua mandarina".

Later on, many linguistically comprehensive systems were made by the Protestants, such as the Legge romanization. In their missionary activities they had contact with many languages in Southeast Asia, and they created systems that could be used consistently across all of the languages they were concerned with. Robert Morrison created his own system.

Wade-Giles

The first system to be widely accepted was the (1859) system of the British diplomat Thomas Wade,[lower-alpha 4] revised and improved by Herbert Giles into the (1892) Wade-Giles system. Apart from the correction of a number of ambiguities and inconsistencies within the Wade system, the innovation of the Wade-Giles system was that it also indicated tones.

A major drawback of the Wade-Giles system was that it demanded the use of apostrophes, diacritical marks, and superscript digits (such as Ch'üeh4), all of which, despite their crucial significance, were often omitted in non-specialist texts; therefore, without matched character(s), the "Chinese" syllables did not convey the Mandarin pronunciation and might be deeply ambiguous.[lower-alpha 5]

EFEO system

The system devised in 1902 by Séraphin Couvreur of the École française d'Extrême-Orient was used in most of the French-speaking world to transliterate Chinese until the middle of the 20th century, after what it was gradually replaced by hanyu pinyin.

Postal romanization

Postal romanization, standardized in 1906, combined traditional spellings, local dialect, and "Nanking syllabary." Nanking syllabary is one of various romanization systems given in a popular Chinese-English dictionary by Herbert Giles. It is based on Nanjing pronunciation. The French administered the post office at this time. The system resembles traditional romanizations used in France. Many of these traditional spellings were created by French missionaries in the 17th and 18th centuries when Nanjing dialect was China's standard. Postal romanization was used only for place names.

Yale system

The Yale Romanization system was created at Yale University during World War II to facilitate communication between American military personnel and their Chinese counterparts. It uses a more regular spelling of Mandarin phonemes than other systems of its day.[lower-alpha 6]

This system was used for a long time, because it was used for phrase-books and part of the Yale system of teaching Chinese. The Yale system taught Mandarin using spoken, colloquial Chinese patterns. Furthermore, in the 1960s and 1970s, in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States, the choices of learning simple or traditional characters and using either Hanyu Pinyin or Gwoyeu Romatzyh had political overtones of aligning with the Communist Party of China or the Kuomintang respectively. Many Overseas Chinese and Western academics took sides. The Yale textbooks, Yale teaching system, and Yale Romanization system represented a "third way" and appeared, consequently, as a kind of neutral choice. The Yale system has since been superseded by the Chinese Hanyu Pinyin system.

Chinese systems

Qieyin Xinzi

The first modern indigenous Chinese romanization system, the Qieyin Xinzi ("New Phonetic Alphabet") was developed in 1892 by Lu Zhuangzhang (盧戇章) (1854–1928). It was used to write the sounds of the Xiamen dialect of Southern Min.[6] Some people also invented other phoneme systems.[7][8][9]

Gwoyeu Romatzyh

In 1923, the Kuomintang Ministry of Education instituted a National Language Unification Commission which, in turn, formed an eleven-member romanization unit. The political circumstances of the time prevented any positive outcome from the formation of this unit.[10]

A new voluntary working subcommittee was independently formed by a group of five scholars who strongly advocated romanization. The committee, which met twenty-two times over a twelve-month period (1925–1926), consisted of Zhao Yuanren, Lin Yutang, Qian Xuantong, Li Jinxi (黎锦熙), and one Wang Yi.[11] They developed the Gwoyeu Romatzyh system, proclaimed on September 26, 1928. The most distinctive aspect of this new system was that, rather than relying upon marks or numbers, it indicated the tonal variations of the "root syllable" by a systematic variation within the spelling of the syllable itself. The entire system could be written with a standard QWERTY keyboard.

| “ | ...the call to abolish [the written] characters in favour of a romanized alphabet reached a peak around 1923. As almost all of the designers of [Gwoyeu Romatzyh] were ardent supporters of this radical view, it is only natural that, aside from serving the immediate auxiliary role of sound annotation, etc., their scheme was designed in such a way that it would be capable of serving all functions expected of a bona fide writing system, and supersede [the written Chinese] characters in due course.[12] | ” |

Despite the fact that it was created to eventually replace Chinese characters, and that it was constructed by linguists, Gwoyeu Romatzyh was never extensively used for any purpose other than delivering the pronunciation of specific Chinese characters in dictionaries.[lower-alpha 7] And, while the "within syllable" indication of the tone made sense to Western users, the complexity of its tonal system was such that it was never popular with Chinese users.[lower-alpha 8]

Latinxua Sinwenz

The work towards constructing the Latinxua Sinwenz system began in Moscow as early as 1928 when the Soviet Scientific Research Institute on China sought to create a means through which the large Chinese population living in the far eastern region of the U.S.S.R. could be made literate,[lower-alpha 9] facilitating their further education.

This was significantly different from all other romanization schemes in that, from the very outset, it was intended that the Latinxua Sinwenz system, once established, would supersede the Chinese characters.[15] They decided to use the Latin alphabet because they thought that it would serve their purpose better than Cyrillic.[16] Unlike Gwoyeu Romatzyh, with its complex method of indicating tones, Latinxua Sinwenz system does not indicate tones at all, and it is not Mandarin-specific and so could be used for other Chinese varieties.

The eminent Moscow-based Chinese scholar Qu Qiubai (1899–1935) and the Russian linguist V.S. Kolokolov (1896–1979) devised a prototype romanization system in 1929.

In 1931 a coordinated effort between the Soviet sinologists B.M. Alekseev, A.A. Dragunov and A.G. Shrprintsin, and the Moscow-based Chinese scholars Qu Qiubai, Wu Yuzhang, Lin Boqu (林伯渠), Xiao San, Wang Xiangbao, and Xu Teli established the Latinxua Sinwenz system. The system was supported by a number of Chinese intellectuals such as Guo Moruo and Lu Xun, and trials were conducted amongst 100,000 Chinese immigrant workers for about four years[lower-alpha 10] and later, in 1940–1942, in the communist-controlled Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Border Region of China.[17] In November 1949, the railways in China's north-east adopted the Latinxua Sinwenz system for all their telecommunications.[18]

For a time, the system was very important in spreading literacy in Northern China; and more than 300 publications totalling half a million issues appeared in Latinxua Sinwenz.[15] However:

In 1944 the latinization movement was officially curtailed in the communist-controlled areas [of China] on the pretext that there were insufficient trained cadres capable of teaching the system. It is more likely that, as the communists prepared to take power in a much wider territory, they had second thoughts about the rhetoric that surrounded the latinization movement; in order to obtain the maximum popular support, they withdrew support from a movement that deeply offended many supporters of the traditional writing system.[19]

Hanyu Pinyin

In October 1949, the Association for Reforming the Chinese Written Language was established. Wu Yuzhang (one of the creators of Latinxua Sinwenz) was appointed Chairman. All of the members of its initial governing body belonged to either the Latinxua Sinwenz movement (Ni Haishu (倪海曙), Lin Handa (林汉达), etc.) or the Gwoyeu Romatzyh movement (Li Jinxi (黎锦熙), Luo Changpei, etc.). For the most part, they were also highly trained linguists. Their first directive (1949–1952) was to take "the phonetic project adopting the Latin alphabet" as "the main object of [their] research";[20] linguist Zhou Youguang was put in charge of this branch of the committee.[21][22]

In a speech delivered on January 10, 1958,[lower-alpha 11] Zhou Enlai observed that the Committee had spent three years attempting to create a non-Latin Chinese phonetic alphabet (they had also attempted to adapt Zhuyin Fuhao) but "no satisfactory result could be obtained" and "the Latin alphabet was then adopted".[23] He also emphatically stated:

| “ | In future, we shall adopt the Latin alphabet for the Chinese phonetic alphabet. Being in wide use in scientific and technological fields and in constant day-to-day usage, it will be easily remembered. The adoption of such an alphabet will, therefore, greatly facilitate the popularization of the common speech [i.e. Putonghua (Standard Chinese)].[24] | ” |

The development of the Hanyu Pinyin system was a complex process involving decisions on many difficult issues, such as:

- Should Hanyu Pinyin's pronunciation be based on that of Beijing?

- Was Hanyu Pinyin going to supersede Chinese written characters altogether, or would it simply provide a guide to pronunciation?[lower-alpha 12]

- Should the traditional Chinese writing system be simplified?

- Should Hanyu Pinyin use the Latin alphabet?[lower-alpha 13]

- Should Hanyu Pinyin indicate tones in all cases (as with Gwoyeu Romatzyh)?

- Should Hanyu Pinyin be Mandarin-specific, or adaptable to other dialects and other Chinese varieties?

- Was Hanyu Pinyin to be created solely to facilitate the spread of Putonghua throughout China?[lower-alpha 14]

Despite the fact that the "Draft Scheme for a Chinese Phonetic Alphabet" published in "People's China" on March 16, 1956 contained certain unusual and peculiar characters, the Committee for Research into Language Reform soon reverted to the Latin Alphabet, citing the following reasons:

- The Latin alphabet is extensively used by scientists regardless of their native tongue, and technical terms are frequently written in Latin.

- The Latin alphabet is simple to write and easy to read. It has been used for centuries all over the world. It is easily adaptable to the task of recording Chinese pronunciation.

- While the use of the Cyrillic alphabet would strengthen ties with the U.S.S.R., the Latin alphabet is familiar to most Russian students, and its use would strengthen the ties between China and many of its Southeast Asian neighbours who are already familiar with the Latin alphabet.

- As a response to Mao Zedong's remark that "cultural patriotism" should be a "weighty factor" in the choice of an alphabet: despite the fact that the Latin alphabet is "foreign" it will serve as a strong tool for economic and industrial expansion; and, moreover, the fact that two of the most patriotic Chinese, Qu Qiubai and Lu Xun, were such strong advocates of the Latin alphabet indicates that the choice does not indicate any lack of patriotism.

- On the basis that the British, French, Germans, Spanish, Polish and Czechoslovakians have all modified the Latin alphabet for their own usage, and because the Latin alphabet is derived from the Greek alphabet, which, in turn came from Phoenician and Egyptian, there is as much shame attached to using the Latin alphabet as there is in using Arabic numerals and the conventional mathematical symbols, regardless of their point of origin.[27]

The movement for language reform came to a standstill during the Cultural Revolution and nothing was published on language reform or linguistics from 1966 to 1972.[28] The Pinyin subtitles that had first appeared on the masthead of the People's Daily newspaper and the Hong Qi ("Red Flag") Journal in 1958 did not appear at all between July 1966 and January 1977.[29]

In its final form Hanyu Pinyin:

- was used to indicate pronunciation only

- was exclusively based on the pronunciation of the Beijing dialect

- included tone marks

- embodied the traditional "initial sound", "final sound", and "suprasegmental tone" model

- was written in the Latin alphabet

Hanyu Pinyin has developed from Mao's 1951 directive, through the promulgation on November 1, 1957 of a draft version by the State Council,[lower-alpha 15] to its final form being approved by the State Council in September 1978,[lower-alpha 16] to being accepted in 1982 by the International Organization for Standardization as the standard for transcribing Chinese.[33]

John DeFrancis has described Mao Zedong's belief that pinyin would eventually replace Chinese characters, but this has not come to pass.[34]

Variations in pronunciation

"The Chinese and Japanese repository" stated that romanization would standardize the various differing pronunciations Chinese often had for one word, which was common for all mostly unwritten languages:

"Those who know anything of the rude and unwritten languages of the other parts of the world will have no difficulty in imagining the state of the spoken dialects of China. The most various shades of pronunciation are common, arising from the want of the analytic process of writing by means of an alphabet. A Chinaman has no conception of the number or character of the sounds which he utters when he says mau-ping; indeed one man will call it maw (mor)-bing, and another mo-piang, without the first man perceiving the difference. By the people themselves these changes are considered to be simple variations, which are of no consequence. And if we look into the English of Chaucer's or of Wickliffe's time, or the French of Marco Polo's age, we shall find a similar looseness and inattention to correct spelling, because these languages were written by few, and when the orthography was unsettled. Times are changed. Every poor man may now learn to read and write his own language in less than a month, and with a little pains he may do it correctly with practice. The consequence is that a higher degree of comfort and happiness is reached by many who could never have risen above the level of the serf and the slave without this intellectual lever. The poor may read the gospel as well as hear it preached, and the cottage library becomes a never-failing treasury of profit to the labouring classes."[35]

See also

- Comparison of Chinese romanization systems

- Transliteration of Chinese

- Transcription into Chinese characters

- Romanization of Japanese

Notes

- ↑ Chao (1968, p.172) calls them "split reading characters".

- ↑ Note that Chinese was only written vertically until modern times. The People's Daily did not print its Chinese characters left-to-right until January 1, 1956. [2] and other printed literature took a long time to follow.

- ↑ But compare The Grand Scribe's Records by Ssu-ma Chʻien ; William H. Nienhauser, Jr., editor ; Tsai-fa Cheng ... [et al.], translators. Bloomington 1994-present, Indiana University Press, which uses Wade-Giles for all historic names (including the author).

- ↑ Wade's system, introduced in 1859, was used by the British Consular Service.

- ↑ For example, the sixteen different syllabic sounds indicated, in Wade-Giles, as Chu1, Chu2, Chu3, Chu4, Chü1, Chü2, Chü3, Chü4, Ch'u1, Ch'u2, Ch'u3, Ch'u4, Ch'ü1, Ch'ü2, Ch'ü3, Ch'ü4 could all end up appearing as "Chu"; some of these represent multiple words without the Chinese characters, but no system of Romanization can fully resolve that.

- ↑ For example, it avoids the orthographic alternations between 'y' and 'i', 'w' and 'u', 'wei' and 'ui', 'o' and 'uo', etc. that are part of the Pinyin and Wade-Giles systems.

- ↑ Such as, for example, Lin (1972), and Simon (1975).

- ↑ Seybolt and Chiang (1979) believe that a second reason was that, subsequent to the promulgation of the Gwoyeu Romatzyh system in 1928, "the increasingly conservative National Government, led by the Guomindang, lost interest in, and later suppressed, efforts to alter the traditional script".[13] Norman (1988): "In the final analysis, Gwoyeu Romatzy failed not because of defects in the system itself, but because it never received the official support it would have required to succeed; perhaps more importantly, it was viewed by many as the product of a group of elitist enthusiasts, and lacked any real popular base of support."[14]

- ↑ Principally the Chinese immigrant workers in Vladivostok and Khabarovsk.

- ↑ The "Soviet experiment with latinized Chinese came to an end [in 1936]" when most of the Chinese immigrant workers were repatriated to China (Norman, 1988, p.261). DeFrancis (1950) reports that "despite the end of Latinxua in the U.S.S.R. it is the opinion of the Soviet scholars who worked on the system that it was an unqualified success" (p.108).

- ↑ Two different translations of the speech are at Zhou (1958) and Zhou (1979).

- ↑ If intended to supersede the Chinese written characters, then the ease of writing the pronunciation (including tones) in a cursive script would be critical.

- ↑ Mao Zedong and the Red Guards were strongly opposed to the use of the Latin alphabet. [25]

- ↑ For example, an American delegation that visited China in 1974 reported that "the principal uses of pinyin at present are to facilitate the learning of Chinese characters, and to facilitate the speed of Putonghua popularization, primarily for Chinese-speakers but also for minorities and foreigners." [26]

- ↑ It was adopted and promulgated by the Fifth Session of the First National People's Congress on February 11, 1958.[30] The 1957 draft was titled "First draft of phonetic writing system of Chinese (in Latin alphabet", while the 1958 version was titled "Phonetic scheme of Chinese".[31] The crucial difference was the removal of the term "Wenzi" (writing system); this explicitly indicated that the system was no longer intended to eventually replace Chinese written characters, but only to act as an auxiliary to assist pronunciation.

- ↑ As a consequence of this approval, Pinyin began to be used in all foreign language publications for Chinese proper names, as well as by Foreign Affairs and the Xinhua News Agency [from January 1, 1979].[32]

References

Citations

- ↑ Kane, Daniel (2006). The Chinese Language: Its History and Usage. North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle. p. 22. ISBN 0-8048-3853-4.

- ↑ Chappell (1980), p.115.

- 1 2 Yves Camus, "Jesuits' Journeys in Chinese Studies"

- ↑ "Dicionário Português-Chinês : Pu Han ci dian : Portuguese-Chinese dictionary", by Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci; edited by John W. Witek. Published 2001, Biblioteca Nacional. ISBN 972-565-298-3. Partial preview available on Google Books

- ↑ Mungello, David E. (1989). Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology. University of Hawaii Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-8248-1219-0. The transcription of the Nestorian Stele can be found in pp. 13-28 of China Illustrata, which is available online on Google Books. The same book also has a catechism in Romanized Chinese, using apparently the same transcription with tone marks (pp. 121-127).

- ↑ Chen (1999), p.165.

- ↑ 建国前的语文工作

- ↑ 國音與說話

- ↑ 拼音史话

- ↑ DeFrancis (1950), p.74.

- ↑ DeFrancis (1950), pp.72–75.

- ↑ Chen (1999), p.183.

- ↑ Seybolt and Chiang (1979), p.19

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp.259–260

- 1 2 Chen (1999), p.186.

- ↑ Hsia (1956), pp.109–110.

- ↑ Milsky (1973), p.99; Chen (1999), p.184; Hsia (1956), p.110.

- ↑ Milsky (1973), p.103.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p.262.

- ↑ Milsky (1973), p.102 (translated from People's Daily of October 11, 1949).

- ↑ "Father of pinyin". China Daily. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ Branigan, Tania (21 February 2008). "Sound Principles". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ Zhou (1958), p.26.

- ↑ Zhou (1958), p.19.

- ↑ Milsky (1973), passim.

- ↑ Lehmann (1975), p.52.

- ↑ All five points paraphrased from Hsia (1956), pp.119–121.

- ↑ Chappell (1980), p.107.

- ↑ Chappell (1980), p.116.

- ↑ Chappell (1980), p.115.

- ↑ Chen (1999), pp.188–189.

- ↑ Chappell (1980), p.116.

- ↑ See List of ISO standards, ISO 7098: "Romanization of Chinese"

- ↑ DeFrancis, John (June 2006). "The Prospects for Chinese Writing Reform". Sin-Platonic Papers. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ↑ James Summers (1863). REV. JAMES SUMMERS, ed. The Chinese and Japanese repository, Volume 1, Issues 1-12. p. 114. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

Those who know anything of the rude and unwritten languages of the other parts of the world will have no difficulty in imagining the state of the spoken dialects of China. The most various shades of pronunciation are common, arising from the want of the analytic process of writing by means of an alphabet. A Chinaman has no conception of the number or character of the sounds which he utters when he says mau-ping; indeed one man will call it maw (mor)-bing, and another mo-piang, without the first man perceiving the difference. By the people themselves these changes are considered to be simple variations, which are of no consequence. And if we look into the English of Chaucer's or of Wickliffe's time, or the French of Marco Polo's age, we shall find a similar looseness and inattention to correct spelling, because these languages were written by few, and when the orthography was unsettled. Times are changed. Every poor man may now learn to read and write his own language in less than a month, and with a little pains he may do it correctly with practice. The consequence is that a higher degree of comfort and happiness is reached by many who could never have risen above the level of the serf and the slave without this intellectual lever. The poor may read the gospel as well as hear it preached, and the cottage library becomes a never-failing treasury of profit to the labouring classes.

(Princeton University) LONDON: W. H. ALLEN And CO. Waterloo Place; PARIS: BENJ. DUPRAT, Rue du Cloltre-Saint-Benoit; AND AT THE OFFICE OF THE CHINESE AND JAPANESE REPOSITORY, 31, King Street, Cheapside, London.

Sources

- Anon, Reform of the Chinese Written Language, Foreign Languages Press, (Peking), 1958.

- Chao, Y.R., A Grammar of Spoken Chinese, University of California Press, (Berkeley), 1968.

- Chappell, H., "The Romanization Debate", Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, No.4, (July 1980), pp. 105–118.

- Chen, P., "Phonetization of Chinese", pp. 164–190 in Chen, P., Modern Chinese: History and Sociolinguistics, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1999.

- DeFrancis, J., Nationalism and Language Reform in China, Princeton University Press, (Princeton), 1950.

- Hsia, T., China's Language Reforms, Far Eastern Publications, Yale University, (New Haven), 1956.

- Ladefoged, Peter; & Maddieson, Ian. (1996). The sounds of the world's languages. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-19814-8 (hbk); ISBN 0-631-19815-6 (pbk).

- Ladefoged, Peter; & Wu, Zhongji. (1984). Places of articulation: An investigation of Pekingese fricatives and affricates. Journal of Phonetics, 12, 267-278.

- Lehmann, W.P. (ed.), Language & Linguistics in the People's Republic of China, University of Texas Press, (Austin), 1975.

- Lin, Y., Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1972.

- Milsky, C., "New Developments in Language Reform", The China Quarterly, No.53, (January–March 1973), pp. 98–133.

- Norman, J., Chinese, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1988.

- Ramsey, R.S.(1987). The Languages of China. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01468-X

- San Duanmu (2000) The Phonology of Standard Chinese ISBN 0-19-824120-8

- Seybolt, P.J. & Chiang, G.K. (eds.), Language Reform in China: Documents and Commentary, M.E. Sharpe, (White Plains), 1979.

- Simon, W., A Beginners' Chinese-English Dictionary Of The National Language (Gwoyeu): Fourth Revised Edition, Lund Humphries, (London), 1975.

- Stalin, J.V., "Concerning Marxism in Linguistics", Pravda, Moscow, (20 June 1950), simultaneously published in Chinese in Renmin Ribao, English translation: Stalin, J.V., Marxism and Problems of Linguistics, Foreign Languages Press, (Peking), 1972.

- Wu, Y., "Report on the Current Tasks of Reforming the Written Language and the Draft Scheme for a Chinese Phonetic Alphabet", pp. 30–54 in Anon, Reform of the Chinese Written Language, Foreign Languages Press, (Peking), 1958.

- Zhou, E., "Current Tasks of Reforming the Written Language", pp. 7–29 in Anon, Reform of the Chinese Written Language, Foreign Languages Press, (Peking), 1958.

- Zhou, E., "The Immediate Tasks in Writing Reform", pp. 228–243 in Seybolt, P.J. & Chiang, G.K. (eds.), Language Reform in China: Documents and Commentary, M.E. Sharpe, (White Plains), 1979.

- MacGillivray, Donald (1907). A Mandarin-Romanized dictionary of Chinese (2 ed.). Printed at the Presbyterian mission press. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

External links

- Donald MacGillivray (1907). A Mandarin-Romanized dictionary of Chinese (2 ed.). Printed at the Presbyterian mission press. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- China Christian Educational Association (1904). Primer of the standard system of Mandarin romanization. SHANGHAI: Printed at the Amer. Presbyterian Mission Press. p. 78. Retrieved 2011-05-15.(the University of California)

- Educational Association of China, F E. Meigs (1905). The standard system of Mandarin romanization, Volume 2. Printed at American Presbyterian Mission Press. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- Educational Association of China (1904). The standard system of Mandarin romanization: introduction, sound table, and syllabary. SHANGHAI: American Presbyterian Mission Press. p. 100. Retrieved 2011-05-15.(the University of California)

- Educational Association of China, F E. Meigs (1904). The standard system of Mandarin romanization, Volume 2. SHANGHAI: Printed at American Presbyterian Mission Press.

- Mandarin Chinese Pinyin Table the complete listing of all Pinyin syllables and their variations used in standard Mandarin, along with native speaker pronunciation for each syllable

- Overview of Chinese phonetic transcription

- Java-based tool for converting texts into different romanization systems

- Chinese romanization

- www.pinyin.info

- www.romanization.com

- Chinese Phonetic Conversion Tool - Converts between Pinyin, Zhuyin, and other formats

| ||||||||||