Romanesque architecture in Spain

Romanesque architecture in Spain is the architectural style reflective of Romanesque architecture, with peculiar influences both from architectural styles outside the Iberian peninsula via Italy and France as well as traditional architectural patterns from within the peninsula. Romanesque architecture was developed in and propagated throughout Europe for more than two centuries, ranging approximately from the late tenth century until well into the thirteenth century.

During the eighth century, though Carolingian Renaissance extended its influence to Christian Western Europe, Christian Spain remained attached to the traditional Hispano-Roman and Gothic culture, without being influenced by European cultural movements, until the arrival of the Romanesque.

Romanesque architecture spread throughout the entire northern half of Spain, reaching as far as the Tagus river, at the height of the Reconquista and Repoblación, movements which greatly favoured the Romanesque development. The First Romanesque style spread from Lombardy to the Catalan region via the Marca Hispánica, where it was developed and from where it spread to the rest of the peninsula with the help of the Camino de Santiago and the Benedictine monasteries. Its mark was left especially on religious buildings (eg cathedrals, churches, monasteries, cloisters, chapels) which have survived into the twenty-first century, some better preserved than others. Civil monuments (bridges, palaces, castles, walls and towers) were also built in this style, although few have survived.

Background and historical context

The Romanesque period corresponds to a time when Christianity was more secure and optimistic. Europe had seen, in the preceding centuries, the decline of the Carolingian splendour and had undergone Norman and Hungarian invasions (the Hungarians reached as far as Burgundy) that resulted in the destruction of many of the peninsula's monasteries. In Spain the Almanzor campaigns were disastrous, also razing and destroying many of the monasteries and small churches.

Towards the end of the tenth century, a number of stabilizing events restored some balance and tranquillity in Europe, greatly easing the political situation and life in Christendom. The main forces that emerged were the Ottomans and the Holy Roman Empire, including the pope, whose power became universal and who had the power in Rome to crown emperors. In Spain the Christian kings were well underway with the Reconquista, signing pacts and cohabitation charters with the Muslim kings. Within this context an organizational spirit emerged throughout Christendom with the monks from Cluny. Monasteries and churches were built during these years and architecture was geared towards more durable structures to withstand future attack as well as fire and natural disasters. The use of a vault instead of a wood covering spread throughout Europe.

Additionally communications were re-established and there was rapprochement between various European monarchs as well as restored relations with Byzantium. The Roman legacy of roads and highways allowed better communication between the numerous monasteries and facilitated pilgrimages to the holy places or small enclaves of popular devotion. As a result, commerce was increased and the movement of people disseminated new lifestyles, among which was the Romanesque style. Shrines, cathedrals, and others, were built in the Romanesque style over nearly two and a half centuries.

Artists and professionals

In the Middle Ages, the concept of "architect" – as understood amongst the Romans – fell out of use, giving way to a social change. The duties of the former architect came to rest on the master builder. This was an artist who, in most cases, took part in the actual construction along with the team of workers which he had under his command. The master builder was the one who oversaw the edifice (as the ancient architect did), but at the same time could also be a craftsman, a sculptor, a carpenter or stonecutter. This person was usually educated in monasteries or groups of unionized masonic lodges. Many of these master builders were the designers of gorgeous portals or porticos, such as the one at the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral made by Master Mateo, the portico of the Nogal de las Huertas in Palencia, by Master Jimeno, or the north portal of the San Salvador de Ejea de los Caballeros Church (in Zaragoza province) by Master Agüero.

All Romanesque architectural work was made up of the director (master builder), a foreman in charge of a large group forming workshops of stonecutters, masons, sculptors, glassmakers, carpenters, painters and many other trades or specialties, who moved from one place to another. These crews formed workshops from which local masters often emerged, who were able to raise rural churches. In this set we must not forget the most important figure, the patron or developer, without whom the work would not be completed.

From documents that have survived in Spain about works contracts, litigation and other issues, it is known that a house or living accommodation was allocated in the cathedrals for the master and his family. There are litigation documents that speak of the problems of the widow of a master, where she claimed for herself and her family a house for life. In some cases, this issue presented a real conflict as the subsequent master of the building would also need to occupy the house.

The master builders frequently had to commit themselves for a lifetime if the work were long-term, as was the case of Master Mateo with the construction of the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral or Master Ramon Llambard (or Raimundo Lambardo) with the Santa Maria de Urgel Cathedral. There was a provision in the contracts requiring that masters always provide: their daily presence on site and strict control of workers and of the progress of the building.

A work house was also always built for the preparation of materials and carving of the stone. Many fourteenth-century documents[1] speak of this house:

La obra de iglesia de Burgos que há unas casas cerca de la dicha iglesia en que tienen todas las cosas que son menester para la dicha obra; e los libros de las cuentas é todas las otras herramientas con que labran los maestros en la dicha obra.(Spanish)

(The construction of the Burgos church that has some houses near the said church in which they have all the things that are necessary for said work; and the books of the accounts and all other tools with which the masters labour in the said work.)[1]

Stonemasons

Stonemasons formed the bulk of workers in the erection of the building. The number of stonecutters could vary depending on the local economy. Some of these numbers are known, such as the Old Cathedral of Salamanca, which employed between 25 and 30. Aymeric Picaud in his Codex Calixtinus provides data that:

[...] with about 50 other stonemasons who worked there regularly, under the caring direction of Don Wicarto (con aproximadamente otros 50 canteros que allí trabajaban asiduamente, bajo la solícita dirección de don Wicarto)[...][2]

These masons and other workers were exempted from paying taxes. They were separated in two groups depending on their specialization. The first group those who were engaged in a special high-quality work (genuine sculpting artists) and who worked at their own pace, leaving their completed work at the site to be later placed on the building. The second group were permanent employees, who raised buildings stone upon stone and put in place those quality pieces or carved reliefs done by the first group at the right time. This way of working could lead to a time lag in the pieces being placed some time after being created, a lag in many cases which has become a big problem for historians in dating the building.

There was also a group of unskilled labourers who worked wherever there was a need. In many cases these people offered their work or skill as an act of mercy because as Christians they were willing to collaborate on a great work dedicated to their God. In any case they received a remuneration that was either by the day or per piece. In documents many names appear on lists of daily wages so this act was not arbitrary but rather well regulated.

Among the Cistercians they became known as cuadrillas de ponteadores (scoring crews),[3] made up of laymen or monks who moved from one county to another, always under the direction of a professional monk, whose job it was to pave grounds, build roads, or build bridges.

Anonymity and artists' signatures

Most Romanesque works are anonymous in the sense of lacking a signature or proof of authorship. Even if the work is signed, specialists historians sometimes have difficulty distinguishing whether reference is made to the actual creator or the sponsor of the work. Sometimes however, the signature is followed or preceded by an explanation that clarifies whether it is one or the other person. Arnau Cadell made it clear on the Sant Cugat capital: This is the image of Arnau Cadell sculptor who built this cloister for posterity.

Rodrigo Gustioz also wanted to be immortalized for his funding of an arch in the Santa Maria de Lebanza: Rodrigo Gustioz made this arc, a man from Valbuena, soldier, pray for him.

This notice by another sponsor appears on a capital:

El prior Pedro Caro hizo esta iglesia, casa, claustro y todo lo que aquí está fundado en el año 1185. (Spanish)

Prior Pedro Caro made this church, house, cloister and everything here was founded in 1185.

In other cases it is the systematic study of the sculpture along with the architecture that has allowed historians to draw conclusions. Thus it is known that in the Lleida Cathedral, Pere de Coma served as master builder from 1190-1220, but during that period there were also several clearly differentiated sculpture workshops. The same study conducted in the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral suggests Master Mateo as the promoter and director of successive workshops which has aspects performed by different hands but under one coherent direction.[1]

The fact that most Romanesque works have remained anonymous has developed the theory that the artist considered that he was not the right person to place his name on works dedicated to God. However, on one hand, the few civil works that remain are not signed either and on the other hand, such a view is countered by a long list that could be given of artists who sign their works themselves, among which are:

- Raimundo de Monforte, which appears in 1129 documents as contracted to build the Lugo Cathedral.

- Pedro Deustamben, appears on a funeral epitaph in San Isidoro de León as builder of the domes.

- Raimundo Lambard or Lambardo, who worked from 1175 on the Urgell Cathedral.

- Masters Bernardo el Viejo, Roberto and Esteban who worked on the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral.

- Master Pere de Coma, who worked in the late twelfth century on the Lleida Cathedral.

- Master Micaelis, who worked on several churches and chapels in northern Palencia, and left his portrait while working on the portal of San Cornelio & San Cipriano in Palencia.

The list could be extended with many more names which appeared right on the stone itself by way of signature or on procurement documents, as proof that the intended construction was neither prohibited nor discouraged.[1] What is difficult to distinguish in many cases is the trade of the person signing as they could either be architects, specialized stonemasons or sculptors of selected pieces. All of them were often called Master and all used his craft during the construction according to the wishes and the mandate of the promoters and patrons.

Developers and sponsors

In the Romanesque world both the promoter of the works as well as the patron and financier were the true stars of the architectural work or the work of art to be created. They are in charge and determine how the work should be done, what should be the characters or the saints in sculpture and reliefs, the geometric dimensions (which then will be the responsibility of the true professional to carry them out with mathematical rigor) and they encourage and exalt the project. The promoters were in charge of hiring and also calling the best artists and architects who worked with their momentum and enthusiasm.

Especially in sculpture and painting, the artist was fully submitted to the will of the patrons and sponsors, without whose intervention the work would never be done. The Romanesque artist adapted to the will of these people giving the best work of his trade and complying with the satisfaction of a job well done without having any desire nor intending to acquire worldwide fame as he began to develop from the Renaissance. The pride of a job well done and the recognition of his peers and patron were the greatest of the awards and so sometimes this pride led them to put it very simply in one of his finished works.

In Spain, kings and a minority of the nobility introduced the new Romanesque trends early on (which carried with it a Benedictine renewal and acceptance of the Roman Liturgy), while another part of the nobility and most of the bishops and monks still clung to the old ways and the Hispanic liturgy. However the Romanesque fully triumphed and this was mainly due to the patrons and promoters who carried out great works from which the new style was developed throughout the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula.

Abbot Oliba was a patron, sponsor and huge promoter of Romanesque art in Catalonia from an early date. In 1008 he was appointed abbot of the monasteries in Ripoll and Cuixá and ten years later he was appointed bishop of Vich. His travels to Rome (1011 and 1016) and his contact with Franco monasticism, accounted for his knowledge of the Roman liturgy and its introduction into the Catalan Church. The Benedictine reform in Cluny had a considerable impact on Cuixá with which Oliba maintained close relations. Oliba adopted Cluny's standards, both in architecture as well as customs and under his patronage and direction major reforms were carried out, new buildings or in other cases mere extensions to suit the needs of the times. During these initial years Abbot Oliba endeavored to be present at consecrations - meetings in which discussions regarding a particular construction, etc. were held. Oliba, during the period between 1030 and 1040[4] was the driving force behind important buildings such as:

- Church of Sant Vicenç, completely rebuilt.

- Montserrat and Montbuy Monasteries.

- The Ripoll, Cuixá, St-Martin-du-Canigou and Vic Monasteries, the latter of which he was personally and directly involved.

- Sant Pere de Rodes.

- Girona Cathedral.

Architectural schools in Spain

In Spain geographical schools of architecture such as those in France, are not easily distinguished, because they are usually mixed with other architectural forms. However there are a variety of buildings that can be clearly identified, if not entirely but to a large extent, as following the pattern of these French schools:

- The Auvergne School seen in the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral and the San Vicente Basilica in Avila.

- The Poitou School, with Santo Domingo de Soria and most twelfth-century Catalan churches, such as Sant Pere de Rodes and Sant Pere de Galligants.

- The Périgord School, examples of which are now part of the transition to the Gothic, such as the Toro Collegiate (except its Byzantine-influenced dome).

Local variations

Each kingdom, region or geographic region of the peninsula, and some human events (such as the Camino de Santiago), marked a distinctive style influenced by the geographical environment itself, by tradition, or simply by the gangs of hired masons and builders who moved from one place to another. As a result, in Romanesque architecture in Spain there are variations such as Catalan Romanesque, Aragonese Romanesque, Palencia Romanesque, Castilian and Leónese Romanesque, among others.

Another fact to consider is the survival of the Moorish populations, who formed gangs of workers and artists who gave a special stamp to buildings. These are what is known as brick Romanesque or Moorish Romanesque.

Romanesque periods

In Spain, as in the rest of the Western Christian world, Romanesque art developed over three stages with their own characteristics. Historiography has defined these stages as early Romanesque, full Romanesque and late Romanesque.

- First Romanesque:[5] architecture comprises a well-defined geographical area that runs from northern Italy, Mediterranean France, Burgundy and Catalan and Aragonese lands in Spain. It developed from the late tenth century until the middle of the eleventh century, except in isolated locations. During this Romanesque period, there were neither miniature paintings nor monumental sculptures.

- Full Romanesque: developed from east towards Lisbon and from the south of Italy to Scandinavia. It spread, thanks to the monastic movement, the unification of the Catholic faith with the Roman liturgy and communication channels along the routes. It began its launch in the first half of the eleventh century and continued until mid-twelfth century. The best examples are in the "pilgrimage churches" (eg the Santiago cathedral), especially in areas of the repoblación. It is characterized by the inclusion of monumental sculptures in the portals and spandrels and for the decoration and styling of the capitals, mouldings, fascias, etc.

The Jaca Cathedral was one of the first temples – if not the first – that was elevated with the aesthetic ideas and architecture of this Romanesque style which entered the peninsula with large French Romanesque influences. The decoration of its imposts and Romanesque arches with geometric themed checkerboard played a role in many of the buildings that were later built, giving this style the name of beleaguered or chequered Jaques.

- Late Romanesque: chronologically it was diffused from the end of the full Romanesque period until the first quarter of the thirteenth century, when it began to be succeeded by Gothic art. This period was the busiest in terms of the construction of monasteries by the Cistercian monks.

Construction of Romanesque buildings in Spain

Romanesque religious buildings were never as monumental as the French constructions, or the constructions that later gave rise to Gothic art. The first buildings designs had thick walls and small openings through which a dim light could enter from outside. Later there was an evolution in the construction of the walls allowing the buildings to be better lightened and for opening bigger windows.

The monastic buildings were the most numerous sharing importance with the cathedrals. Churches and parishes were constructed in cities while in small towns countless small churches, known as rural Romanesque, were built.

Material

The most precious but also the most expensive material was the stone. The stonemasons busied themselves carving it with a chisel, always selecting the good face of the block. These were made into ashlars, which were generally available in horizontal rows and sometimes used along the edges. Hard rocks were almost always used. Masonry was also used, with hewn stone in the corners, windows and doors. If the stone was hard to get, because the corresponding geographic location had no quarries, or because it was too expensive at certain times, they used baked brick, slate or any ashlars stone. Paint and plaster were used as finish, both for the stone as well as for the masonry and the other materials, so that, once the walls were painted, it was difficult to distinguish whether it had one or the other underneath. Colourful Romanesque architecture was as widespread as it had been in Roman buildings.[1]

Foundations

Medieval builders did extensive study for the foundation, taking into account the type of building that was to be built, the materials that were to be used and the ground upon which the building would be laid. First deep ditches were dug and were filled with stones and rubble. Trenches were distributed under the walls that would go over them and others were made crosswise in order to join the passageways together and strengthen the pillars of the transverse arches. The foundation formed a network that practically sketched the plan of the temple, thus differing from the isolated foundation for the support of the pillars used in the Gothic style. In some ruined churches all that remains is this foundation, giving archaeologists good study material. Archaeologists are able to determine the thickness of the walls from these revealed remains of the foundations, although it is known that in this respect the builders rather exaggerated and made excessively deep trenches and overly thick foundation for fear of landslides.

Vaults, naves and ceilings

During the First Romanesque period, many rural churches were still being covered with a wooden roof, more so in Catalonia and especially in the Boi Valley where the Romanesque renewal of old churches was done by Lombard builders who covered the gabled naves with a wooden structure, respecting the old traditions of the region. However, the apse in these churches was always topped with an oven vault.

Throughout the eleventh century, naves were covered with barrel vaults, either a half barrel or a quarter barrel, a device used in Romanesque architecture throughout Europe. Later the groin vault was used. In Catalonia, these barrel vaults were used without reinforcements, while in Castile and León arches were used as support. The use of the groin vault (arising from the crossing of two perpendicular barrel vaults) had been lost and was later taken up by great master builders. The groin vault in turn gave way to the ribbed vault, which later became very common in Gothic architecture.

The type of vaults used exclusively on the stairs of the towers were also called helical vaults. Examples of their use are at San Martín de Fromista, Sant Pere de Galligants and San Salvador de Leyre, among others.

Corner vaults were built in the cloisters of monasteries and cathedrals. These result from the meeting of two groups in a cloister. The finishing of these vaults was not very easy, so builders had to use various tricks that ensured that flaws were not easily visible to the naked eye.

Arches

In Spain the most used arch was the semicircular although the horseshoe arch and the pointed arch were also used. The arch was used exclusively throughout the eleventh century and first half of the twelfth century. In order to achieve certain heights, the vaults were made quite stilted, as in Sant Joan de les Abadesses. Many arcs were built doubled with the intention that they would be stronger. Later, in the portals, arches were formed with archivolts, i.e. a sequence of concentric arches decorated with simple or decorative plants or geometric mouldings.

Pointed arches came from the Orient. It is unknown the exact date of their use in Romanesque architecture in Spain, although historians proposed some dates based on buildings containing one or more pointed arches that sometimes spawn an entire vault in some of its parts. There are buildings that correspond to the first quarter of the twelfth century, such as the Lugo and Santa Maria de Terrassa cathedrals. The early use of these arcs became a construction element which provided many advantages. It was an architectural breakthrough that the Cistercian monks were able to see from the beginning.

Buttresses

Buttresses are continuous thick vertical walls that are placed at the sides of an arch or vault to counteract attacks. They were also placed on the outer walls of the naves of churches or cloisters. In Romanesque architecture are always visible is one of the elements that characterize it, especially in Spanish architecture, except in the Catalonia area where construction was done adopting a greater thickness of the walls.

Covers

The buildings were covered with a roof that could be made of different materials:

- Stone (used frequently). These covers can still be seen in the Gallo tower of the old of Salamanca cathedral and the Ávila Cathedral.

- Roof tile - capable of being changed frequently, the material resists weathering over time.

- Glazed sheets, rare materials. It is located in the spire of the tower of the former Valladolid.

- Slate, especially in areas where this material is abundant, especially in Galicia.

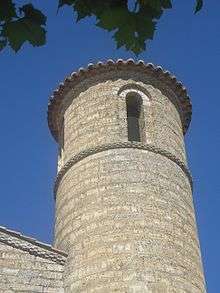

Towers

In Spanish buildings towers are located in different parts of the church - on the sides, over the transept and, in very special cases, over the straight section of the apse, as in the churches of the city of Sahagún in León. This placement was because, being built of brick (a material less consistent than stone), the builders had to locate the towers in the strongest, more resistant section (usually at the apses). A façade made up of two towers was not very common and usually seen only in temples of great importance.

Towers served as steeples, especially in the Romanesque styles in Castile and León, they are what are called Turres signorum. In many cases they were built as defence towers, especially in border territories experiencing military conflict, and the location of the tower depended on what was being defended. Thus the tower of the church of the Silos monastery was located to defend the monastery, the tower of the San Pedro de Arlanza monastery was a very important defence for the entire area. The military aspect of these Romanesque towers evolved and changed over time so that at present it is difficult to guess at their original purpose or purpose for which they were used in other eras. In many cases these towers were attached to the sides of the church, and some even completely independent of the churches.

Bell-gables

A gable is an architectural element that is usually built on the façade and used, instead of a tower, to house the bells. The bell-gable (referred to as espadaña in the Iberian peninsula) was built as a vertical continuation of the wall and the spans were opened to receive the bells. The gable was easier and cheaper to build. In Spanish Romanesque they were very numerous especially in smaller rural Romanesque churches. They were made of a single span or several terraced storeys. They usually had pointed or pinion tops.[6]

There are all kinds of gables in the Romanesque style of Campoo and Valderredible. There are some spectacular ones in other locations such as the one at Agullana in the Alto Ampurdán or the Astudillo, with five openings. There are more modest ones such as at the Santa Maria de Valbuena Monastery where its veins also have a unique placement.

Paintings

During the Romanesque era, a building was not considered finished until its walls had appropriate paintings.[7] The walls of the most important and significant parts (especially the apses) were lined inside with iconographic paintings, many of which have come down to the twenty-first century, such as those belonging to churches in the Tahull Valley.[8] The walls, both inside and out, were covered with a layer of paint in one color and the imposts, vains and columns were highlighted in the original material, but sometimes they were also painted in bright colors: green, yellow, ocher, red and blue. This custom of painting or revoking the buildings was not new or unique to the Romanesque of the Middle Ages but represented an inheritance or continuity of the construction method from olden times.

Whether the material used was stone, ashlar or if the masonry was in bricks, the finish was a painted surface. Thus, in many cases it could not be determined if the exterior was made of stone or brick, which could only be determined from plaster scrapings. The paint finish gave the buildings protection against environmental assaults but these were removed in the nineteenth-century when theories were applied to expose the original building materials.

Some of these paintings have remained in certain buildings, as a testimony of the past, on walls, sculptures and capitals. On the façade of the San Martín de Segovia Church, traces of paint were still visible into the twentieth century, as witnessed and described by the Spanish historian Marqués de Lozoya. Sometimes carving the baskets of the capitals was too expensive and they were left completely smooth so that the painter could finish them with floral or historical motifs. In the San Paio de Abeleda church in Ourense, there are vestiges of paintings on some capitals, which have even been repainted throughout its history. Fragments of capitals with their original painting have been found among the ruins of the San Pedro de Arlanza monastery and they give an indication of how the rest was decorated.

Cistercian and Premonstratensians monks also painted the walls of their churches, in white or a light earthy color, and they sometimes outlined the joints of the blocks.

Sculptures

The use of sculptures as decoration for buildings during the full Romanesque period was something so commonplace that it was considered a necessity. Architecture and sculpting represented an inseparable iconographical program. The idea of the Church (an idea developed and disseminated by the Benedictines of Cluny), was to teach Christian doctrine through the sculptures and paintings of the apses and interior walls. The capitals of the columns, the spandrels, the friezes, the cantilevers and the archivolts of the portals were intricately decorated with stories from the Old and New Testaments. These sculptures were not limited to religious depictions but also covered a number of profane but equally important issues to the eleventh- and twelfth-century population, such as field work, the calendar (as in the case of the capitals of the Santa María la Real de Nieva cloister, from late Romanesque), war, customs, among others. In other buildings real, mythological and symbolic animals were sculpted, plus allegories of vices and virtues (the best example can be given in the erotic corbels of the San Pedro de Cervatos Collegiate in southern Cantabria). These decorations were not always of a historical or animals type; geometric decoration was very important at the beginning of the Romanesque thus floral and plant decoration were also used. Often the carved tympanum or the frieze depicted a series of images along the capitals of the columns of the archivolts.

Churches

The temples of the First Romanesque are simple, with a single nave topped by a semicircular apse (without a transept). The prototype of the Romanesque church was non-rural, medium-sized and with the floor plan of a basilica with three naves containing three semicircular apses and a transept. Throughout the twelfth century the traditional Hispanic type temples with three straight and terraced apses were still being built in some areas (such as in the city of Zamora). Church plans were adapted to the liturgical needs, as the number of canons or friars who required more altars for their religious functions was increasing. Temples were built with Benedictine Cluny-style apses added. A long transept that could accommodate more apses was adopted in Cistercian architecture, and there are more examples of this type of construction. This feature was also adopted by the cathedrals (Tarragona, Lleida, Ourense and Sigüenza). There are also examples of cruciform structures that precisely depict a Latin cross, such as the eleventh-century Santa Marta de Tera church in Zamora, or the San Lorenzo de Zorita del Páramo church in Palencia, whose header is not square but semicircular. There are also circular plans, with a single nave such as the San Marcos church in Salamanca, or the Vera Cruz church in Segovia.

Vestry

In the Romanesque era small churches or parish churches did not have vestries. Vestries were only added to these churches beginning in the sixteenth century. However, in the grand monasteries or cathedrals there was a space adapted in the cloister for this purpose.

Crypts

Crypts are one of the characteristic features of Romanesque architecture. In the First Romanesque, its use spread due to the influence of the Franks. Spaces were built just below the top of the church and were intended for keeping the relics of martyrs, the worship of whom came about from Carolingian influence. They usually had three naves with a groin vault cover, although there are variations, such as the circular crypt with a pillar in the center (Cuixá and Sant Pere de Rodes). Throughout the eleventh century, they began to lose importance as recipients of relics and were instead built for practical and necessary architectural purposes, adapting to the terrain on which the church was built (this is the function of the Monastery of Leyre crypt). Throughout the twelfth century, few crypts were built and those that were built were due to the uneven ground. Later the crypts were converted to funerary purposes.

Tribunes

The tribunes were galleries over the aisles that were used by important people to monitor the liturgy. They had little importance in Romanesque Spain, with their construction being very scarce. Two examples are known: the San Vicente de Avila and the Basilica of San Isidoro. Traditional historiography suggests that, in the latter church, the tribune was a special place for Queen Sancha, wife of Ferdinand I, but more recent studies show that the dates do not match. There is little information on this architecture.

Triforia

A triforium is a gallery with arches running along the top of the lower naves of a church, below the large windows of the main nave. It sometimes surrounds the apse at the same height. Its origin was purely cosmetic, since if the nave was too high there was a heavy space between the ceiling windows and the supporting arches of the lower lateral naves.

At first the arch of the triforium was not set, but it was then thought that it could be used to provide light and ventilation, while leaving a passage for building services and surveillance. This construction could be done because the aisles are always pushed into the central nave, thus leaving a usable hole of the same depth as the width of the aisle. This element had its true development in the Gothic era. In Spanish Romanesque architecture triforia are scarce because the bare wall was usually left in their place or a blind arcade was built.

A good example of a triforium is the Santiago de Compostela cathedral. The aisles of this temple has two floors and the triforium occupies the entire second, covering the entire building and lining the outside by a series of windows that provide light and interior arches. Another example is in the Lugo Cathedral, although in this case it runs along all the walls. In San Vicente de Ávila the triforium is a dark gallery that does not provide light from outside.

In some pilgrimage churches the triforium was at times used as an area for overnight accommodation for pilgrims.[9]

Porticos and galleries

The portico is a space originally designed for preventing inclement weather. It was constructed in both rural and city churches, in front of the main door to protect it. In most cases they were made with a wooden structure that stood the test of time, but in many cases the construction was in stone resulting in galleries of great development, which in some cases were true works of art.

The porticos were reminiscent of the narthex of the Latin basilicas. It formed an advanced body over the central part of the main façade and if this façade had towers then it occupied the space between them, as in the Portico of Glory in the of Santiago de Compostela cathedral. At other times it occupied the entire front, forming a covered space that was called a "Galilee".

Rose windows

Rose windows are circular windows made of stone, whose origin is in the Roman oculus of the basilicas. In Spain these rose windows were employed from the eleventh century. Throughout the Romanesque, rose windows became important and increased in size, culminating in the Gothic era, which produced some of the most beautiful and spectacular specimens.

Cloisters

The cloister is an architectural unit usually built next to cathedrals and monastic churches, attached to the north or south. The cloister par excellence is the one promulgated by the Benedictine monks. The different units of the cloister, hinged on all four sides of a square courtyard, were dedicated to the service of the life of the community. In Spanish Romanesque many cloisters have been preserved, especially in the Catalan region.

Civil and military architecture

The Romanesque civil architecture is almost unheard of and most of the buildings that are considered to be from this period, are not, although some retain parts of the foundation or a door or semicircular window from the Romanesque era, their development and architectural design belong to more modern times.

Civil buildings

Domestic buildings, including palaces, had no great pretensions. Houses were built of flimsy material (as opposed to the grandeur of the churches) and were unable to stand the test of time. When they wished to give importance to the civil architecture, the little that there was transformed and the new one was built with Gothic tendencies. So it was with the so-called Romanesque palace of Diego Gelmírez in Santiago de Compostela, which is actually a totally Gothic factory, or buildings of Segovia sinecures from the Middle Ages.

There is the famous palace of Dona Berenguela in the city of Leon, called a Romanesque palace, but its structure and planning actually correspond to the last years of the late Middle Ages, far from Romanesque, though it retains (perhaps from outside the original location) some Romanesque windows. There is also, in Cuéllar, the Palace of Peter the Cruel, the origin of which is supposed to date from the time of the Repoblación. Maybe part of its foundations are Romanesque, but the current building is from the early fourteenth century, even though it has a Romanesque portal that was perhaps inherited from the previous building or reused from another. This palace is however considered as one of the few examples of civil Romanesque.[10][11] Traditionally, buildings that have a good portal with a semicircular arch and large segments have been called "Romanesque" houses or palaces, but they are actually structures from the Gothic era.

An example of what could be a Romanesque palace built in stone is seen in the façade of the Palace of the Kings of Navarre in Estella, Navarre.

See Also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bango Torviso, Isidro. Tesoros de España (Spanish Treasures). Madrid: Espasa Calpe. ISBN 84-239-6674-7.

- ↑ Cómez Ramos, Rafael; Cómez, Rafael (2006). Los constructores de la España medieval. Universidad de Sevilla. p. 62. ISBN 9788447210176.

- ↑ Lampérez y Romea, Vicente (1935). Historia de la arquitectura cristiana. Manuales Gallach (Madrid: Editorial Espasa Calpe). p. 37.

- ↑ Puig i Cadafalch defined this period as the Golden Age of architecture in Catalonia.

- ↑ The definition was coined by the Spanish architect and historian Puig i Cadafalch in his book La geografía i els origens del primer Art Romanic (The geography and origin of the first Romanesque art), Barcelona 1930.

- ↑ See image

- ↑ Throughout the nineteenth century (and later during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries), a restorative style consisting of exposing the construction materials of the walls emerged, removing all traces of paint both inside and outside, based on misguided historicist theoretical standards from the sixteenth century. Bango Torviso, Isidro G. Tesoros de España. Vol. III. Románico; Blanco Martín, Francisco Javier. Iniciación al Arte Románico. Fundación de Santa María la Real. Aguilar de Campo.

- ↑ See image

- ↑ Guillermo Fatás and Gonzalo M. Borrás (1980). Diccionario de términos de arte y arqueología (Dictionary of Art and Architectural terminology). (in Spanish). Zaragoza: Guara Editorial. ISBN 84-85303-29-6.

- ↑ José Luis Cano de Gardoqui García (2002). Casas y palacios de Castilla y León (Houses and palaces of Castille and Leon) (section on Segovia) (in Spanish). Junta de Castilla y León. ISBN 84-9718-090-9.

- ↑ Bango Torviso, Isidro G. (1994). Historia del Arte de Castilla y León (History of the Art of Leon and Castile). Arte Románico (in Spanish) II (Valladolid: Ámbito Ediciones). p. 39. ISBN 84-8183-002-X.

Bibliography

- Alcalde Crespo, Gonzalo. Iglesias rupestres. Olleros de Pisuerga y otras de su entorno.(Spanish) Edilesa, 2007. ISBN 978-84-8012618-2

- Bango Torviso, Isidro G. Tesoros de España. Vol. III. Románico.(Spanish) Espasa Calpe, 2000. ISBN 84-239-6674-7

- Bango Torviso, Isidro G. Historia del Arte de Castilla y León. Tomo II. Arte Románico.(Spanish) Ámbito Ediciones, Valladolid 1994. ISBN 84-8183-002-X

- Chamorro Lamas, Manuel. Rutas románica en Galicia.(Spanish) Ediciones Encuentro, Madrid 1996. ISBN 84-7490-411-0

- García Guinea, Miguel Ángel. Románico en Palencia.(Spanish) Diputación de Palencia, 2002 (2nd revised edition). ISBN 84-8173-091-2.

- García Guinea, Miguel Ángel, Blanco Martín and Francisco Javier. Iniciación al Arte Románico. La arquitectura románica: técnicas y principios.(Spanish) Fundación de Santa María la Real. Aguilar de Campoo, 2000. ISBN 84-89483-13-2

- García Guinea, Miguel Ángel. Románico en Cantabria.(Spanish) Guías Estudio, Santander 1996. ISBN 84-87934-49-8

- Herrera Marcos, Jesús, Arquitectura y simbolismo del románico en Valladolid.(Spanish) Edita Ars Magna, 1997. Diputación de Valladolid. ISBN 84-923230-0-0

- Lampérez y Romea, Vicente. Historia de la arquitectura cristiana española en la Edad Media.(Spanish) Tomo I. Editorial Ámbito, 1999. ISBN 84-7846-906-0

- Lampérez y Romea, Vicente. Historia de la arquitectura cristiana.(Spanish) Manuales Gallach. Editorial Espasa Calpe, Madrid 1935

- Nuño González, Jaime. Iniciación al Arte Románico: Aportación de la Historia, de la Arqueología y de las ciencias auxiliares al conocimiento del estilo románico.(Spanish) Aguilar de Campoo, 2000. ISBN 84-89483-13-2

- Pijoán, José. Summa Artis. Historia general del arte. Vol. IX. El arte románico siglos XI y XII.(Spanish) Espasa Calpe, Madrid 1949.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

_F0173k.jpg)